Artists Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen have collaborated to absurd and comic effect in the Giardini’s Alvar Aalto Pavilion of Finland. Their installation places two animatronic sculptures at its centre, Geb and Atum, who converse upon a raised platform that is studded with glowing windows. One character is a giant egg and the other is a cardboard box with moving cartoonish eyes and mouth—both are described as super-advanced terraforming aliens. When they talk, videos depicting their experiences are projected as separate acts in a play; these strange scenes involve Muppet-like puppets and are in constant flux as projections move across the walls. One sees Atum entering the interior space of a mutant fleshy being, which is described as “vast and dark and wet and smelly”. This is interrupted by a Chinese version of the philosopher Carl Jung who rediscovers the buried head of a bearded hairy Neanderthal and excitedly beckons: “Share your primal mind with me”. It ends in the bloody stabbing of Jung.

Combining references to archaeology, science fiction and anthropology, the artists mythologise the creation of Finnish society and its future state. While the ridiculous nature of the installation forces laughter, its humour is used to expose the undercurrents of nationalism, xenophobia and intolerance that are all too prevalent in society and politics today (Brexit, Trump and the rise of alt-right politics continuing to undermine any sense of international cohesion and community). Absurdism becomes a tool to undermine regressive socio-political positions.

Having never agreed to exhibit his work in the Venice Biennale, the Swiss Pavilion pays tribute to Modernist Alberto Giacometti with an installation titled Women of Venice. While Carole Bove’s sculptures combine colour, scale and surface texture to powerful effect, artists Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler’s film Flora tells the story of Giacometti’s lover Flora Mayo, who he met in Paris during the 1920s. Using a documentary style, her (now elderly) son recounts her life experiences, restoring an absent subjectivity and reinstating strength and power to a woman who struggled as an artist and single mother. Her story is moving and inspiring, and foregrounded as a primary focus beyond Giacometti himself, redressing the balance to shift emphasis from the dominance of male artists and their stories.

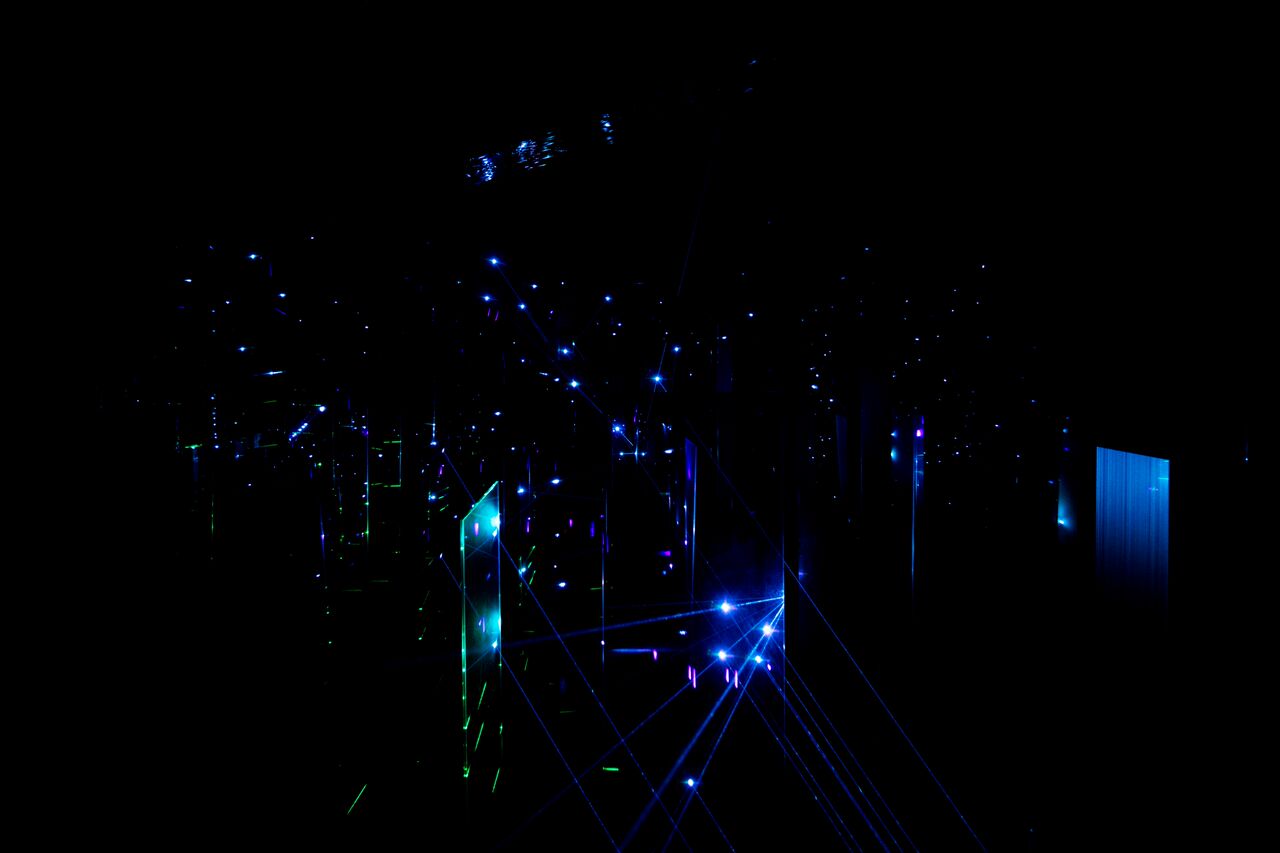

The Danish Pavilion sees Kirstine Roepstorff casting viewers into complete and utter darkness. The thirty-minute theatre piece uses a voiceover commentary that seemingly exists in our subconscious; an argument ensues about why it is necessary to remove us from daylight, purporting that light is distracting, growth only coming from moments of darkness. We are asked to imagine the beginning of time: small, hazy points of light begin to illuminate the stage, which is undeniably beautiful. Yet while it has the potential to be poetic and profound, glass prisms reflecting blue and red lights that dance as star constellations, instead it feels clichéd, scripted and staged, with any intention of creating an immersive escapist world becoming lost. The artist calls for the acceptance of impermanence, the unknown and transformation as a natural part of growth, but with a mystical-cum-psychoanalytic approach that mythologises conditions of healing, it’s hard not to want to run back into the light.

By contrast, Anne Imhof’s Faust at the German Pavilion is compelling. Raised upon a glass platform that extends through the entire architecture, symbolic props are placed underneath including BB gun pellets, a fetish dog collar, teaspoons (the type that you might find lying on the floor of an addict’s house), and a pipeline that leads outside, spilling water into a bleeding, overflowing puddle. Lines drawn with paraffin burn beneath viewer’s feet—a strange vertigo ensuing. Upon this stage, Imhof’s host of disaffected, androgynous youths roam amid ambient sounds, as someone begins to utter a melodic chant that suggests a call to arms. The enigmatic moment feels simultaneously contemporary and mythical, Nike sports gear upon strangely timeless and unknowable characters. At a time where young people face increasing education fees, zero-hour contracts, uncertain pensions and unstable health-care systems, the artist creates a liminal space that reflects an indeterminate future.

At the Arsenale, this year’s Biennale curator Christine Macel’s exhibition Viva Arte Viva is separated into nine chapters, aiming to foreground art as the ultimate platform for reflection, individual expression, freedom and question asking in a world full of conflicts where humanism is jeopardized. The Pavilion of Traditions brings together artists who reinterpret or reinvent history to open up new value systems. Michele Ciacciofera’s sculptural installation Janas Code (2016-17) looks at the contemporaneity of myths through the traditional Sardinian folk legend of domus de janas—funerary structures dug into the rock during the Neolithic era where witches and fairies were said to live. Objects moulded from ceramic are presented on wooden tables, shiny glazes of pale green, pink and yellow coating forms reminiscent of legs, shoes and sacks. Textured panels of wall-mounted honeycomb are stained with smatterings of gold glitter and emit sweet aromas–you can almost imagine creatures climbing out from the tiny, individual cells, disturbed during an archaeological dig.

Guatemalan artist Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s Third Lung (2017) fills a room with pulsing sounds as wall-mounted neon strips illuminate proximate hanging, rock-like stalagmites. Perforated, these contain small clay whistles that play healing melodies. Drawing upon Mayan culture, the environment is intended as a soothing space suspended between two parallel worlds of myth and reality. Similarly meditative is Chilean artist Enrique Ramírez’s film, Un hombre que camina (2011-14). Shot upon the still waters of the Uyuni salt planes in Bolivia, a man walks from one world into another, passing from life into death. Accompanied by a marching brass band and wearing a traditional Diablo nortino mask—used by locals under colonial rule to undermine conquistadors—the man wanders in an almost magical otherworldly landscape, bathed in the pink light of a sunset.

These artists are using myths to imagine alternative realities—past, present and future—and to explain human nature. Roland Barthes’s 1957 book Mythologies looked precisely at myth creation and society’s pastime of creating modern myths, which clearly persists as a methodology in contemporary art. Off-site, Katja Novitskova’s Estonian Pavilion If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen With Your Eyes reinterprets the dystopian world of Philip K. Dick’s Blade Runner, as parasitic forms reminiscent of worms and crabs are simultaneously natural and mechanical. She mythologises a moment in the future where people might uncover relics telling the tale a civilisation’s end. As things fall apart around us, this world doesn’t seem quite as unbelievable as it might once have–even a year ago.