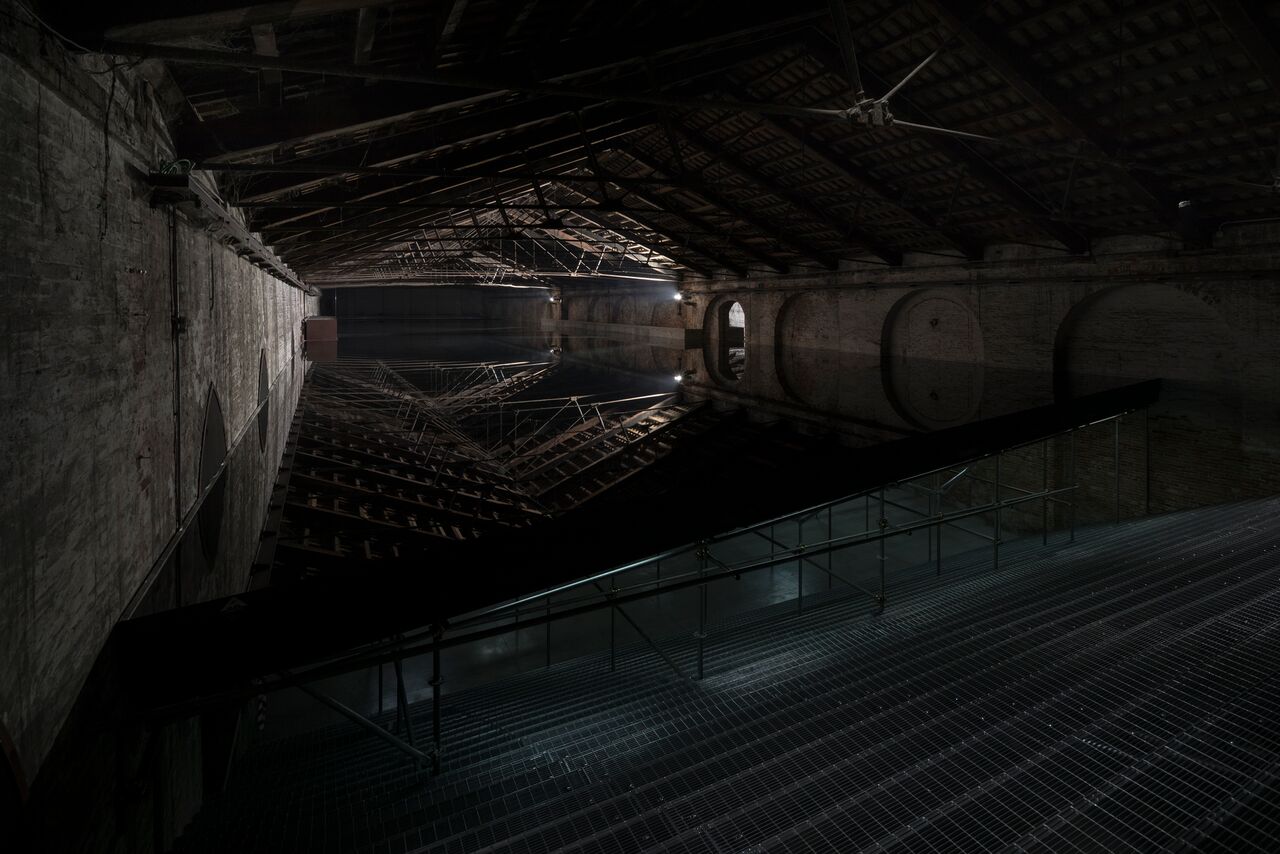

View of the exhibition “The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied.” Fondazione Prada, Venice 13 May 2017 – 26 November 2017 Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti Courtesy Fondazione Prada (Anna Viebrock ‘Palcoscenico’, 2017. Alexander KlugeTerror = Furcht und Schrecken (Terrore = paura e orrore), 2017

Venice is an odd city. It’s made of 121 islands connected by 435 bridges. There are boats instead of cars. Crammed vaporetti awkwardly navigate its waters. Google Maps doesn’t work properly. Its road network is composed of dead ends and narrow alleyways. Its calli and campi are periodically inundated by water sea. During the day, colourful multitudes of tourists populate its streets. When the sun sets, though, they disappear: at night Venice looks like a ghost town.

The opening days of the Biennale makes Venice even more surreal. Ranks of shining yachts are lined up along the Riva degli Schiavoni. Weird sculptures fill the city squares (this year a 65-feet-high golden tower by James Lee Byars has risen in the Campo San Vio, while Damien Hirst’s monstrous sculpture of a horse squeezed by a giant snake menacingly stands in front of Palazzo Grassi). Thousands of artists, curators and socialites from all over the world gather here for one week, transforming the already über-packed town into an eccentric vanity fair. For an art writer like me, the Venice Biennale is certainly an exhausting yet rewarding venture: endless queues outside the must-see pavilions (regularly jumped by aggressive journalists and fancy collectors) are the price to pay for Prosecco parties and free water-taxi rides.

The title of this year Biennale is Viva Arte Viva. According to the curator Christine Macel, the show is a sort of homage to the spiritual and liberating power of art and artists (“Art is the favourite realm for dreams and utopias, a catalyst for human connections that roots us both to nature and the cosmos, that elevates us to a spiritual dimension”; “Art is the last bastion, a garden to cultivate above and beyond trends and personal interests”). Quite a weak, naïve statement that has led Macel to structure the exhibition into nine elementary, a-critical sections (the so-called “trans-Pavilions”: the Pavilion of Joys and Fears, the Pavilion of the Earth, the Pavilion of Traditions etc.). As a result, the show is informed by stereotypes, mixing together ecological thinking, pro-immigrant rhetoric and a “return-to-tradition” attitude (as proved by the Olafur Eliasson intervention, a workshop in which migrants and refugees assemble, together with the public, lamps made of recycled materials). With the exception of a few refreshing works (in the Arsenale, Charles Atlas’s video installation The Tyranny of Consciousness, Jeremy Shaw’s short film Liminals and Alicja Kwade’s sculpture environment made of bronze and mirrors; in the Giardini, Rachel Rose’s animated film Lake Valley and Kiki Smith’s installation of drawings and sculptures), Viva Arte Viva is too politically correct to be compelling; too anachronistic (in terms of curatorial concept) to be engaging and inspiring.

“As the viewers step in, they find themselves in a factory-like installation by Roberto Cuoghi: devotional figures of Christ are here, industrially produced from start to finish through the use of kilns and noisy machines.”

A few national pavilions caught my attention, though. Alongside the celebrated German one, which hosts an unsettling four-hour performance by Anne Imhof (and that was awarded the Golden Lion for the Best National Participation), the Italian pavilion at the Arsenale, curated by Cecilia Alemani, was undoubtedly one of the most intriguing. As the viewers step in, they find themselves in a factory-like installation by Roberto Cuoghi: devotional figures of Christ are here, industrially produced from start to finish through the use of kilns and noisy machines. The environment is dark and disquieting; the visual effect extremely powerful. A video installation by Adelita Husni-Bey and an impressive installation by Giorgio Andreotta Calò occupy the rest of the pavilion. Calò has divided the space, immersed in semi-darkness, into two levels: the lower one, hosting a forest of scaffolding that holds up a wooden platform; and the upper one, in which a layer of water, that creates a suspended lake, reflects the elaborate ceiling. The work generates a disorienting vision, a mirage-like effect: what the artist explores here are the dynamics of aesthetic transfiguration.

James Richards’s project for Wales at Santa Maria Ausiliatrice, a former church just off Via Garibaldi, includes a sound piece, a video and a series of photographs. The strongest work in the show is Music for a Gift, a six-channel music installation conceived by Richards as an emotional response to the building. Field recordings, sound effects and the artist’s own voice, alongside electronically generated and recorded material, mould a kaleidoscopic acoustic landscape that the listener is invited to experience while sitting on a star-shaped bench. Hong Kong and the Nordic Countries deserve a special mention too: the first (located in front of the entrance to the Arsenale) with a project by Samson Young that explores the pop phenomenon of “charity songs”; the second (in the Giardini) with an elegant group exhibition featuring, among others, a sinuous fibreglass installation by Norwegian sculptor Siri Aurdal that looks like a flying wave.

“Any time the viewers open a door, they step into a new stage setting/micro-exhibition–a sort of vital, existential space, containing theatre props, moving images and photographs.”

If Viva Arte Viva, with the exception of a few national pavilions, is overall disappointing (and not very vivace, as the title would seem to suggest), many collateral events and exhibitions in town are worth a visit. The Venice must-see is undoubtedly the group show curated by Udo Kittelmann at Ca’ Corner della Regina, the 18th century palazzo on the Canal Grande where the Fondazione Prada is located. The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied (a title inspired by a song of Leonard Cohen) is a daring and poetic curatorial experiment. Far away from the didactic, rectilinear structure of Viva Arte Viva, the show looks like a labyrinth, in which theatre set designs by Anna Viebrock, photographs and videos by Thomas Demand, and films and writings by Alexander Kluge are blended together “to create–in the curator’s words–a setting, a gravitational field of cross-genre aesthetic practices and social relevance”. Any time the viewers open a door, they step into a new stage setting/micro-exhibition–a sort of vital, existential space, containing theatre props, moving images and photographs. Disorientation is used here to establish inventive connections between works; it is a strategy employed in order to nurture inspiration. This should be a reminder for all the curators and artists gathered in Venice–first of all, for the Artistic Director of the 57th edition of the Biennale.