At a time of rising right-wing nationalism and xenophobia, the Venice Biennale organisers could have taken an important symbolic stand by updating the archaic system of national pavilions to reflect today’s globalized art world. The Biennale was founded in 1895, a time when the globe was largely divided between colonizers and colonized; to still have mostly “first world” nations grouped within the Giardini and others relegated to the outside feels not just anachronistic, but misguided. Not surprisingly, in the absence of leadership from the Biennale organisers, many of the artists and curators participating in the exhibition have taken it upon themselves to present works that challenge received ideas of nationhood, identity and western-centric versions of history.

One of the most subversive–and joyful–shows this year is to be found at the Diaspora Pavilion, whose very name and concept run counter to the notion of national representation, celebrating, as it does, the fruits of the diasporic experience.

Located in an elegant palazzo away from the tourist throngs, the pavilion is entered through a dazzling curtain of gold foil strips, giving the disorienting sense of stumbling into a flashy cabaret. The work, created by Susan Pui San Lok, is accompanied by a soundtrack formed of song clips with the lyric “golden”. The theatricality continues within where one is confronted by Hew Locke’s colourful flotilla of boats sailing through the air, an alluring yet poignant reminder of the themes of migration and displacement at the heart of this pavilion.

The show is the result of a mentorship programme between eleven established artists such as Locke, Isaac Julien and Yinka Shonibare MBE and twelve British-based emerging artists, and has spawned rich dialogues between the two groups. For instance, Shonibare’s spectacular installation British Library, stacked with hundreds of books wrapped in his trademark batik fabric and bearing famous British immigrants’ names, chimes beautifully with Barby Asante’s nearby intervention in which black women appear in small video monitors inserted into the pages of Italian art books and their voices issue forth from a bookshelf. In three other spots around the palazzo, Asante has introduced black women’s voices into the atmosphere as an insistent presence.

In the main gallery, Michael Forbes’s vibrant assemblages juxtapose African masks and statues on plinths with Western collectables such as porcelain Madonnas, rococo figurines and landscape paintings in a melange of cultural references across time and geography that prompt questions about the construction of identity, ethnographic practices, and the objects we value.

Other highlights were Larry Achiampong’s film Sunday’s Best, a moving personal exploration of spirituality and Christian imperialism, contrasting the impassioned evangelical worship at a Ghanaian community centre in London with the heavy pomp of the Catholic Church; Dave Lewis’s photographs of Venice that play with spectatorship and notions of cultural belonging through contrasting images of a Caribbean tourist and African migrant hawkers; and Sokari Douglas Camp’s majestic 2012 work All the world is now richer, composed of six life-sized steel sculptures of men and women representing successive stages in the history of slavery.

These same themes of colonialism, identity and cultural heritage also thread through several other national pavilion exhibitions, in particular, those of New Zealand, Iraq and Tunisia. The centrepiece of New Zealand’s show Emissaries is Lisa Reihana’s extraordinary 23.5 metre-long panoramic video inspired by a nineteenth-century French wallpaper depicting European explorers’ encounters with the “noble savages” of the Pacific. Reihana’s work in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015-17) fuses fact and fantasy in a beguiling animated narrative around the voyages of the British explorer Captain James Cook. However, the artist, who is of Maori and British descent, avoids the exoticizing viewpoint of the original, painting instead a nuanced picture of cultural exchange (and misunderstanding) between the Pacific peoples and the British up to the climactic rupture that occurs with Cook’s murder and dismemberment.

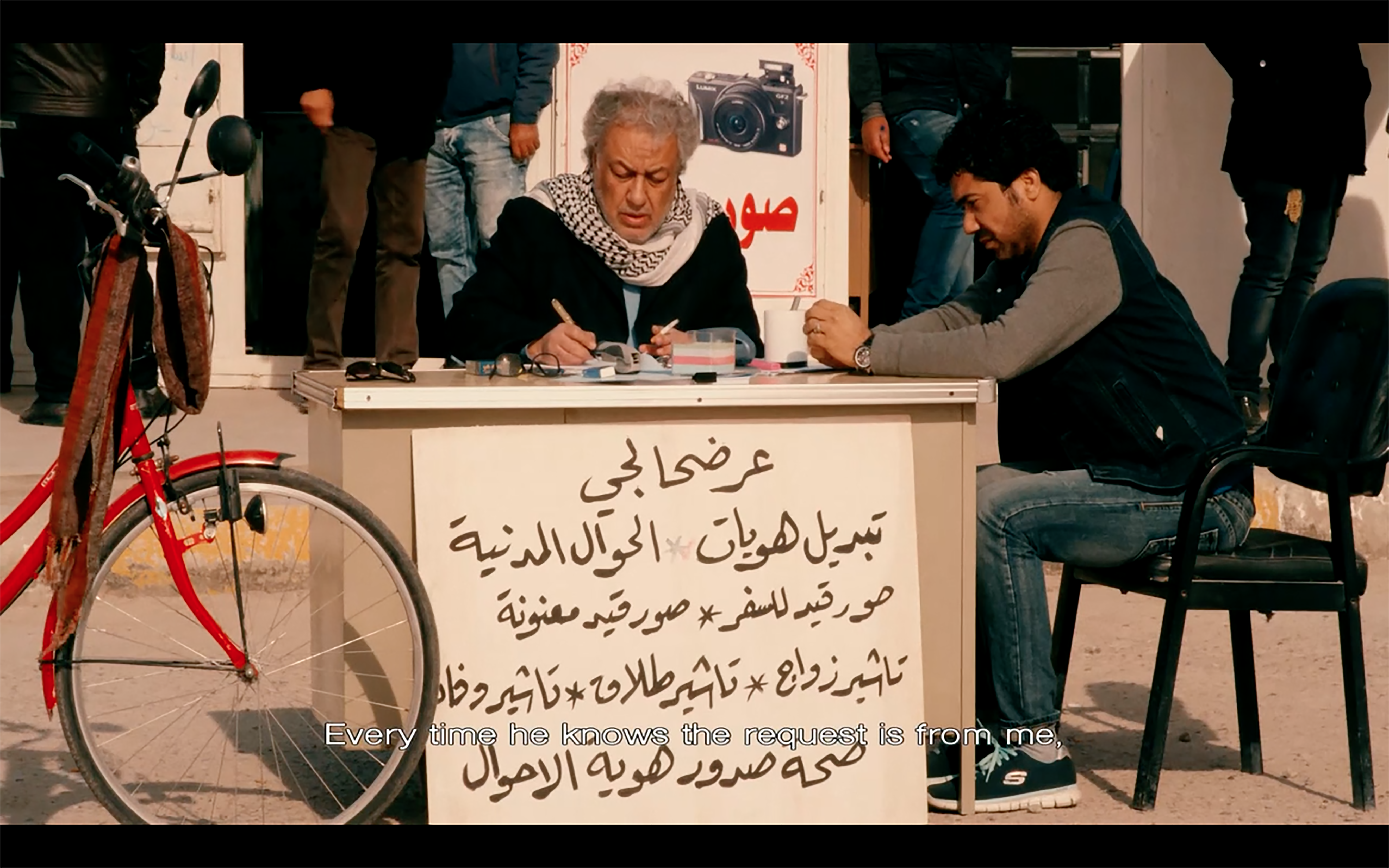

The quest for identity through cultural inheritance underlies the exhibition Archaic which is presented by Iraq, a nation turned upside down by wars and the intervention of foreign powers. Housed in the disused library of a grand palazzo, it brings together forty ancient artefacts with the work of eight contemporary and modern Iraqi artists in a meditation across millennia on loss, conflict and the meaning of civilisation. I found myself haunted by Luay Fadhil’s poetic video The Scribe in which a desperate man repeatedly visits a public scribe to connect with his recently deceased wife. Through this simple framing device, the work interweaves a human tale of grief with the turmoil of present-day Iraq and the country’s venerable literary past. Similarly powerful was Nadine Hattom’s installation comprising photos and sculptures centred on her family’s heritage as part of the now dispersed Mandaean sect from Iran and Iraq. Black and white family photos with the people excised yet retaining the conversational captions about their lives bear testament to this vanishing culture and the complexities of trying to forge an identity from memories and objects. Accompanying this work is a new commission from the Belgian, Mexico-based artist Francis Alÿs which comprises paintings, drawings, photographs and notes exploring the role of the artist in war, based on his experience of being embedded last year with a Kurdish battalion fighting ISIS in Mosul.

Tunisia, another nation struggling to overcome the impact of colonization, posits its vision for a radical new political order in its first national pavilion since 1958. Its exhibition The Absence of Paths features pop-up checkpoints in three venues where visitors are issued with a Universal Travel Document, or “Freesa”, theoretically granting full freedom of movement. The idea is that in the utopian art bubble of Venice, we may discard the state-imposed national classifications that define us. The NSK State Pavilion, run by the artist collective Neue Slowenische Kunst State in Time, founded in 1992, similarly offers passports and rejects accepted notions of citizenship.

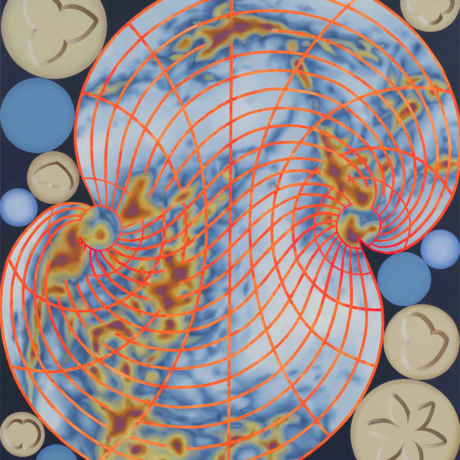

In the American Pavilion power is at play, but not the bullying of a superpower; rather it is the empowerment of the marginalized. African-American artist Mark Bradford offers up an intimate, brutal yet celebratory narrative, possibly reflecting his conflicted feelings about representing an America that voted in Donald Trump and which has so poorly served people of colour through history. Visitors enter the pavilion through the servants’ quarters and are symbolically forced to the margins by a bulbous black pock-marked sculpture Spoiled Foot, which relates to Bradford’s poem Hephaestus (the lame-born Greek god of blacksmiths, sculptors and artisans) inscribed in stone above the entrance. Dominating the second room is a sculpture titled Medusa which is composed of a seething mass of yellow and black coils. Around the walls hang large-scale glistening purple-black paintings made from permanent wave end-papers using hair dye in a reference to Bradford’s mother’s beauty salon. The neoclassical rotunda has been plastered in black and yellow strips of paper, linking it visually to the Medusa, in a swirling vortex titled Saturn Returns. This sense of violent cosmic chaos and reordering continues in the next room with a trio of stunning abstract paintings in textured reds, blacks and creams simultaneously recalling intricate cellular formations and ecstatic planetary explosions. Destruction and creation, ruin and rebirth loom large in this pavilion, suggesting that a new, more equitable world order is called for. Leading by example, Bradford has partnered with a local social cooperative that helps to reintegrate former prisoners and set up a shop selling their artisanal goods–a welcome counter to the ostentatious presence of yachts and bling during the Biennale opening week.

These pavilions–all of which, bar the US, are excluded from the privileged location of the Giardini–grapple with realpolitik, colonial legacy and identity. While some might regard these weighty themes as diametrically opposed to the optimistic “Viva Arte Viva” premise of Christine Macel’s curated show, in fact, the underlying message is not dissimilar. Few would argue that art can change the world. However, in these dismal political times, as the world lurches from one crisis to the next, it would seem that art has the potential to offer a metaphysical domain for tolerance and understanding that bridges national, religious, gender and racial boundaries. As he wrestled with how to respond artistically to human tragedy during his stint at the Mosul frontline, Francis Alÿs postulated in his notebook: “Art can open a space of hope in the midst of hopelessness”. That hope is palpable across the current Biennale.