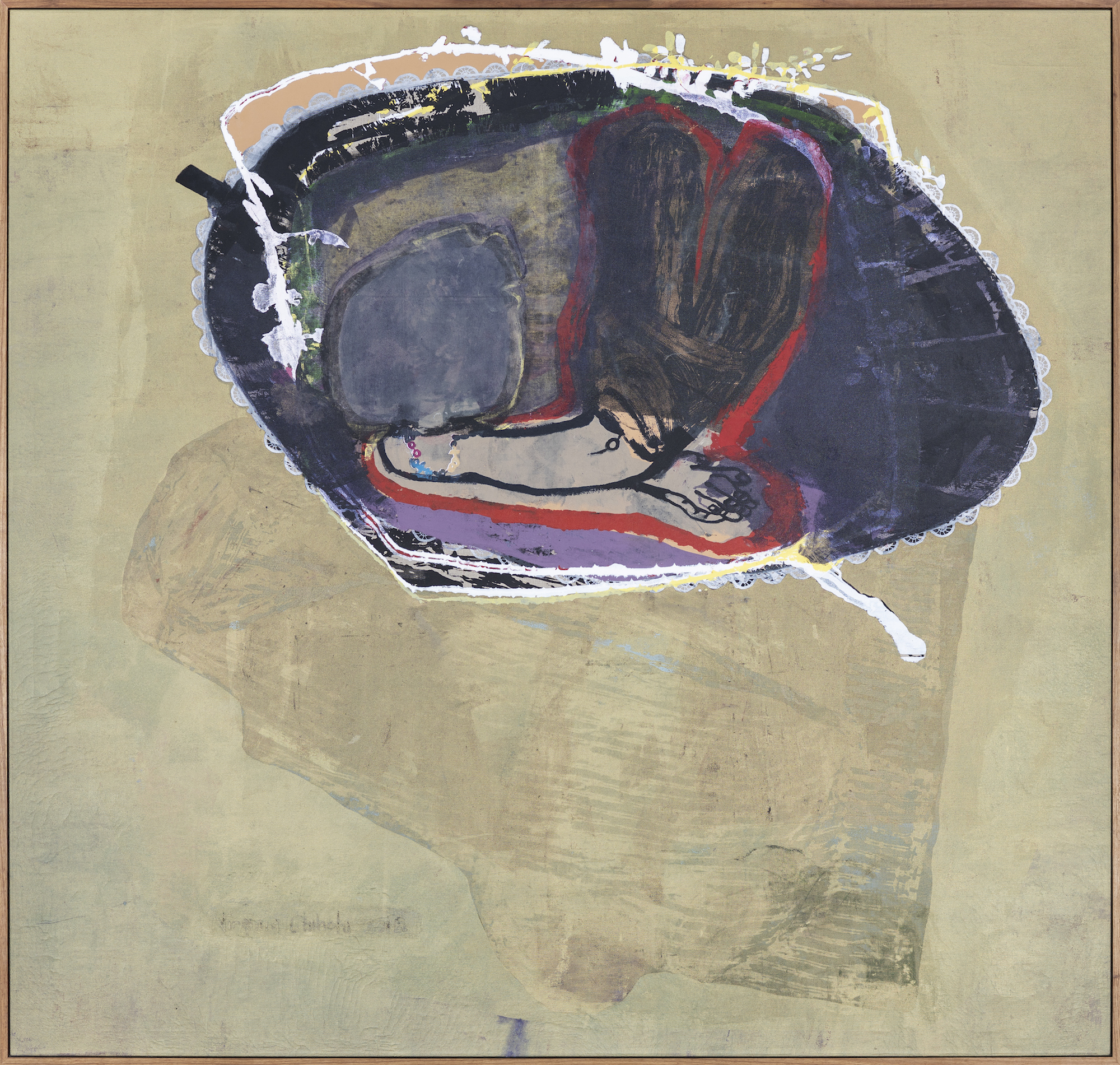

The intimacies of our lives, both individual and collective, are explored in the quietly expressive work of Virginia Chihota. Born and raised in Zimbabwe, she draws upon vignettes from her early years to inform her compositions, questioning the dreamlike nature of memory and the influence of the family unit. The wet layers of paint applied through screen printing build up a form of distortion: a filmy surface through which figures appear and disappear. In these works Chihota reflects upon themes ranging from childbearing to bereavement, marriage to religion, moving between states of calm, distress and elation.

Elaborate patterns and textures populate her work, while graphic, printed elements and the repetition of iconography introduce further layers of personal subjectivity, memory and popular culture. In her latest exhibition at Tiwani Contemporary in London, titled Whose Am I? I Am Not My Own, she navigates feelings of belonging and kinship. Human figures hover or float within clearly defined boundaries, at once protected in safety and simultaneously constrained. The motif of a striking shade of bold red appears throughout, as suggestive of the shared bond of family blood as it is the violence of these same connections—from the gendered expectations of motherhood to the grief of losing a loved one. Through sprawling, colourful and emotive compositions, she captures what it means to be human in an ever-changing world.

Why do you choose to produce your work using silk-screen?

Working with screen printing was never the plan. I wanted to express myself with painting as opposed to printmaking, which I never gave attention to when I was at college. That was until I had to submit printmaking exercises in college (I had received a warning before because I had never submitted a work in printmaking). I had to force myself to be in the printmaking room to print something, hand it over and forget about it. But things turned out not as planned.

Printmaking is a process that you have to go through, doing more preparatory work until you finally are able to print. Somehow, I just found myself embracing the moments and processes that were involved, and not only that, I also found a language to express myself which came effortlessly—as opposed to my paintings which I had always found rigid, and also reminded me of some other artists’ works I had seen.

After going through different printmaking techniques, screen printing came out on top for me as a medium of expression, and I also realised most of the textures and forms I got with other printmaking techniques I could also get using silkscreen. It substituted painting for me; I realised that, in most cases, if not told otherwise most viewers would see my work as a painting not a silkscreen.

“The female figure is very flexible for me as it helps me to express, unfold and find out what I need to learn so I can move on”

What does the recurring female figure in your work represent for you, and how abstract or real is she?

The recurring female figure is a representation of self within my space and thoughts. She helps me to reveal the face and form of my conditions. She is simply trying to understand that which makes her a human being, questioning existence and conditions within her world. She appears in different forms, depending on her condition and what she is questioning, she will always face the front because she longs to confront her fears. Her anatomy appears abnormal and defining her conditions. The female figure is very flexible for me as it helps me to express, unfold and find out what I need to learn so I can move on.

The act of repeating the same image or gesture over and over, I have learned in the process, is my own prayer seeking a solution over a specific matter. When I have been answered, this allows me to start on another unknown journey. The female figure is real to me in forms that I cannot define with words. She carries different appearances just like everyone else. You look in the mirror and today you are happy with how you appear yet tomorrow might be a different story. On another occasion, you may have to dress up and mask up for a party but our outside appearances, I have learned, are not always true selves.

- Left: Ndiri Mwana Wa.... (I am a child of ....), 2019. Right: Ndiri Mwana Wa.... (I am a child of ....), 2018

Textured patterns often appear in your work, as if imprinted from various textiles and familiar domestic items. Where do you source these from, and what personal significance do they have to you?

The textures in the work are sourced from different places and from people that carry a personal significance in my being. Most of these textures are from my past, and I always seem to remember or encounter them in my dreams. When I use it in the work I am usually asking questions about why these specific patterns or textures continue to appear in my space. I also have certain textures that I use repeatedly because I have certain dreams in a specific place, and that place never changes its setup: the curtains are just as they were when I was young in that place, and people are wearing certain clothes that carry certain memories which relate to a specific person.

There is also the presence of plants, flowers and leaves motifs in my work; they are things I did not grow up embracing. Take, for example, receiving flowers on an ordinary day. When I was growing up I mostly encountered flowers when somebody was sick in the hospital. When people brought a bunch of flowers I would always question this act. Had the recipient understood the gesture entirely because I hardly saw them smiling?

My other encounter with flowers had been on funerals where the dead might have never received a single flower when they were living but their graves carry so many flowers. This always made me question flowers as a kind gesture. Now I receive flowers not because I am sick and somehow I feel I don’t respond maybe as I should. I love flowers and they are beautiful but I would like to know beyond that, hence they appear in the work carrying many questions.

“Most of these textures are from my past, and I always seem to remember or encounter them in my dreams”

You grew up in Harare during a time of great political upheaval and change. How has this influenced your work, and what are some of your early memories or encounters with art?

I think growing up in these times you become part of the struggles and the hope that things will change and find a way to adapt, even though you ask questions and you are usually you are told to be quiet, and this creates a sort of self censorship subconsciously. Some of us were able to go to art school which allowed us to question, express and be aware that, irrespective of how things stand, there is a way out and having the chance to express myself in this fashion served as therapy. My early encounter with art was when I was in primary school and I knew instantly where drawing was required. I did not have to struggle or put much effort; it was known and I never thought beyond that.

Hands, feet and limbs are knotted together, or abstracted from the body entirely, in your work. How important is symbolism and iconography in your work, and what do these expressionist gestures stand for?

Their presence enhances my personal expression and interpretation of how I want to express emotions of the human condition as opposed to the way things appear in reality. Symbolism is an important part of my compositions. The anatomy can be whatever it chooses in form and gesture, and not feel out of place and rejected.

All images courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary

Virginia Chihota, Whose Am I? I Am Not My Own (Ndiri Waani? Handisi Muridzi Wangu)

At Tiwani Contemporary until 27 February 2021

VISIT WEBSITE