The Misunderstanding ( La Mésentente ), March 12, 1978

Is it possible to communicate an artist’s philosophy after their death? This endeavour, a foundational purpose of galleries, estates and art historians around the world, is complicated even further when the person in question rejected almost every artistic value those institutions hold dear.

Meet Jean Dubuffet. Born in 1901, he was already an art school dropout before he’d even turned twenty, leaving the prestigious Academie Julien in Paris after just six months. Choosing to pursue his own creativity, he immersed himself in everything from noise music to concrete poetry, all sandwiched between stints working for his family’s wine business.

Cultural propriety and a formal arts education meant little to the French Art Brut founder. His experiments with acrylic paint (which he often mixed with everything from sand and glue to glass, tar, pebbles and even bits of mirror), assemblage, sculpture and drawing spanned a dizzying array of styles, seizing on art history’s treasured conventions and reshaping them with brash, contorted strokes.

“I would like people to see my work as a rehabilitation of scorned values and a work of ardent celebration”

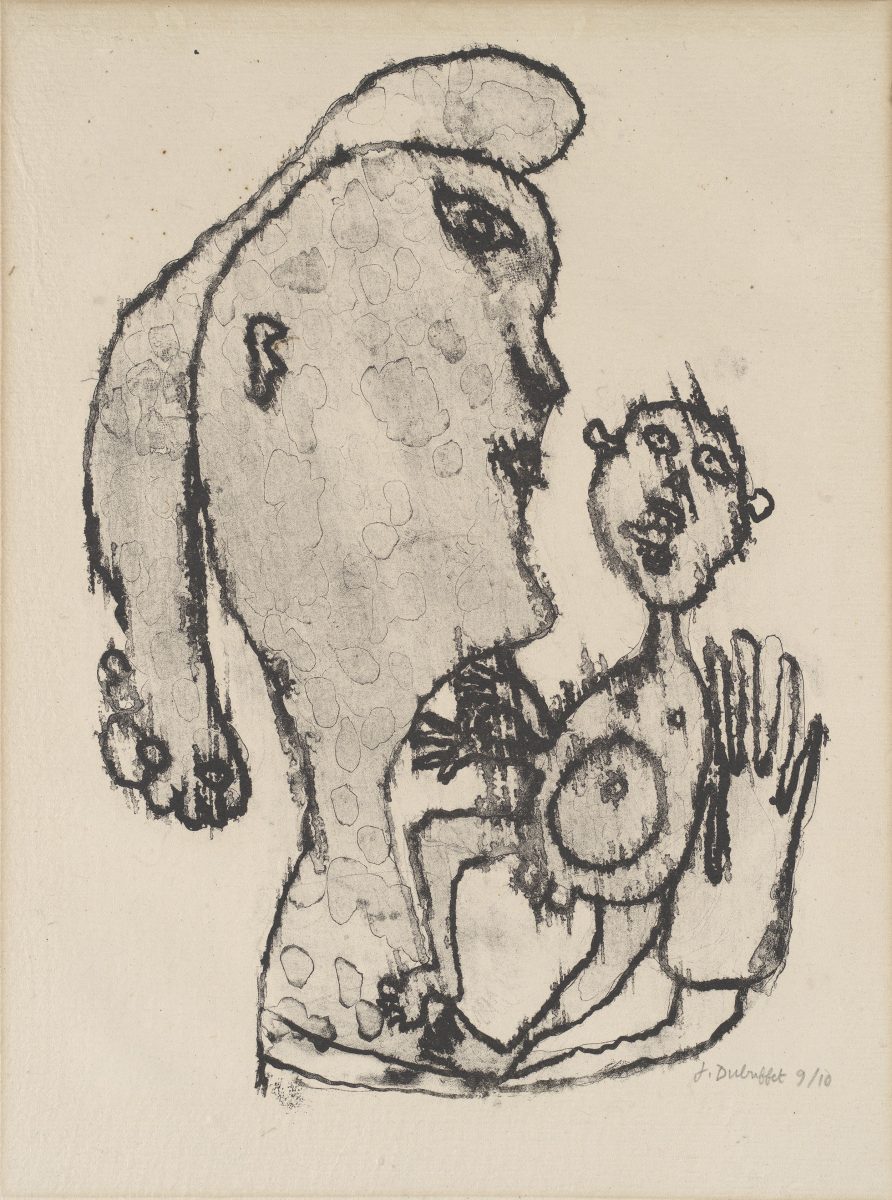

His female nudes resemble splattered cartoons, his textured landscapes protrude from the canvas like lunar surfaces or bodily growths. The crudity of Dubuffet’s portraits, “is entirely consistent with his belief that true beauty could only flourish when conventions of good taste were jettisoned,” wrote Eleanor Nairne, a Barbican curator who worked on the Brutal Beauty Dubuffet retrospective in 2021.

Dubuffet knew what he liked and saw art as an expression of raw feeling, of impulse and experimentation, not an exercise in calculation or conformity. His beliefs, often delivered in biting epigrams, give a sense of perpetual assuredness which suited the subversive nature of his works. “Let the artist’s mind, his moods and impressions, be offered raw, with their smells still vivid, just as you eat a herring without cooking it, but right after pulling it from the sea, when it’s still dripping,” he once said.

In practice, this meant a relaxed attitude towards the conventions of single-material practices, and a disregard for the representative and beauty codes which structured contemporary portraiture and still life, most famously in his Corps de dames (Ladies’ Bodies) works in the early-1950s. By the time the Pompidou Centre opened in 1977, Dubuffet had become “the French establishment’s official rebel,” wrote Jonathan Jones wrote after the 2021 Barbican show.

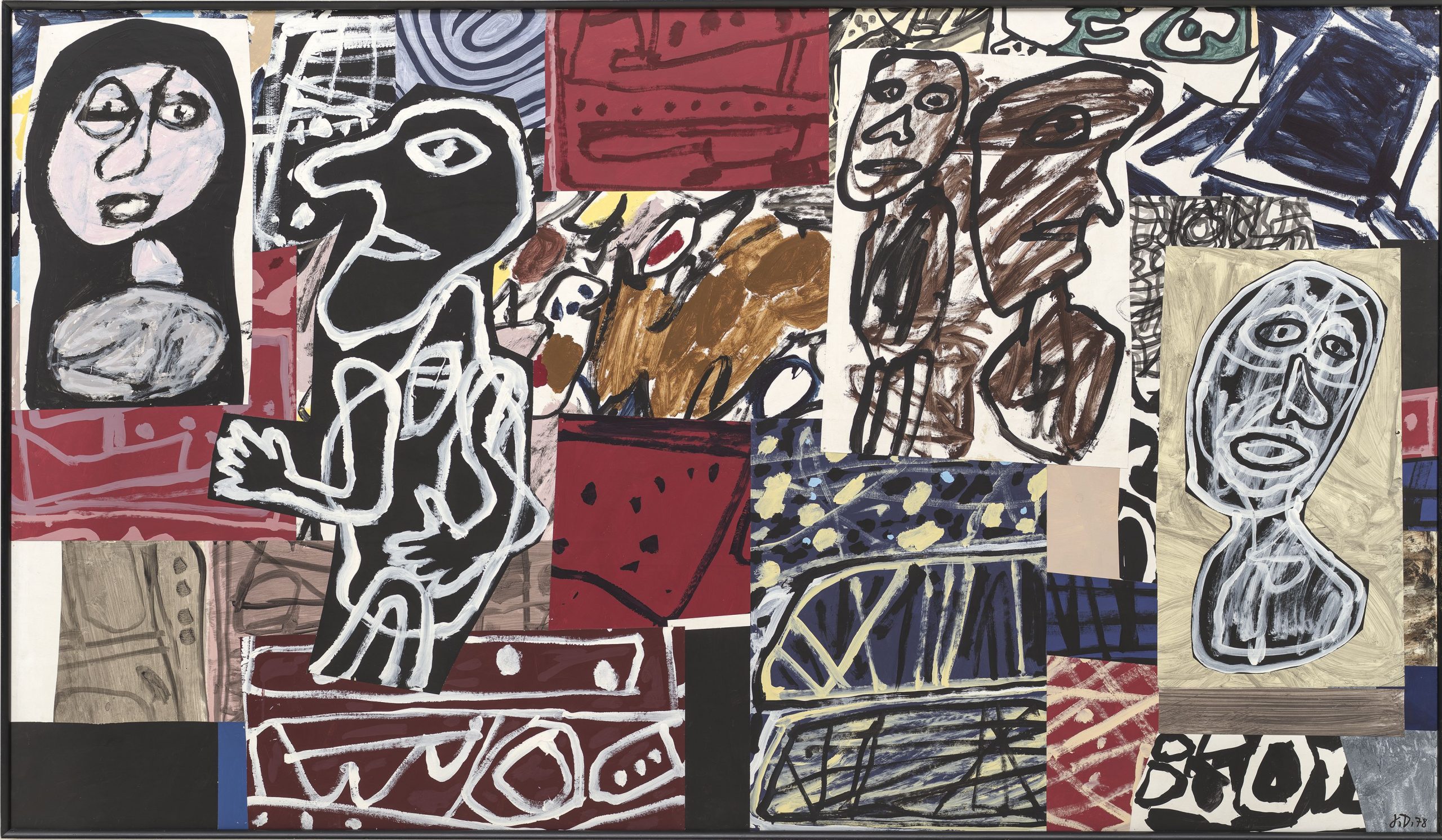

“I would like people to see my work as a rehabilitation of scorned values and.… make no mistake about it, a work of ardent celebration” is their chosen Dubuffet line. Organising his work into early, middle and late periods pays deference to his natural variety: they do not attempt to impose new order on works conceived from disorder.

“Cultural propriety and a formal arts education meant little to the French Art Brut founder”

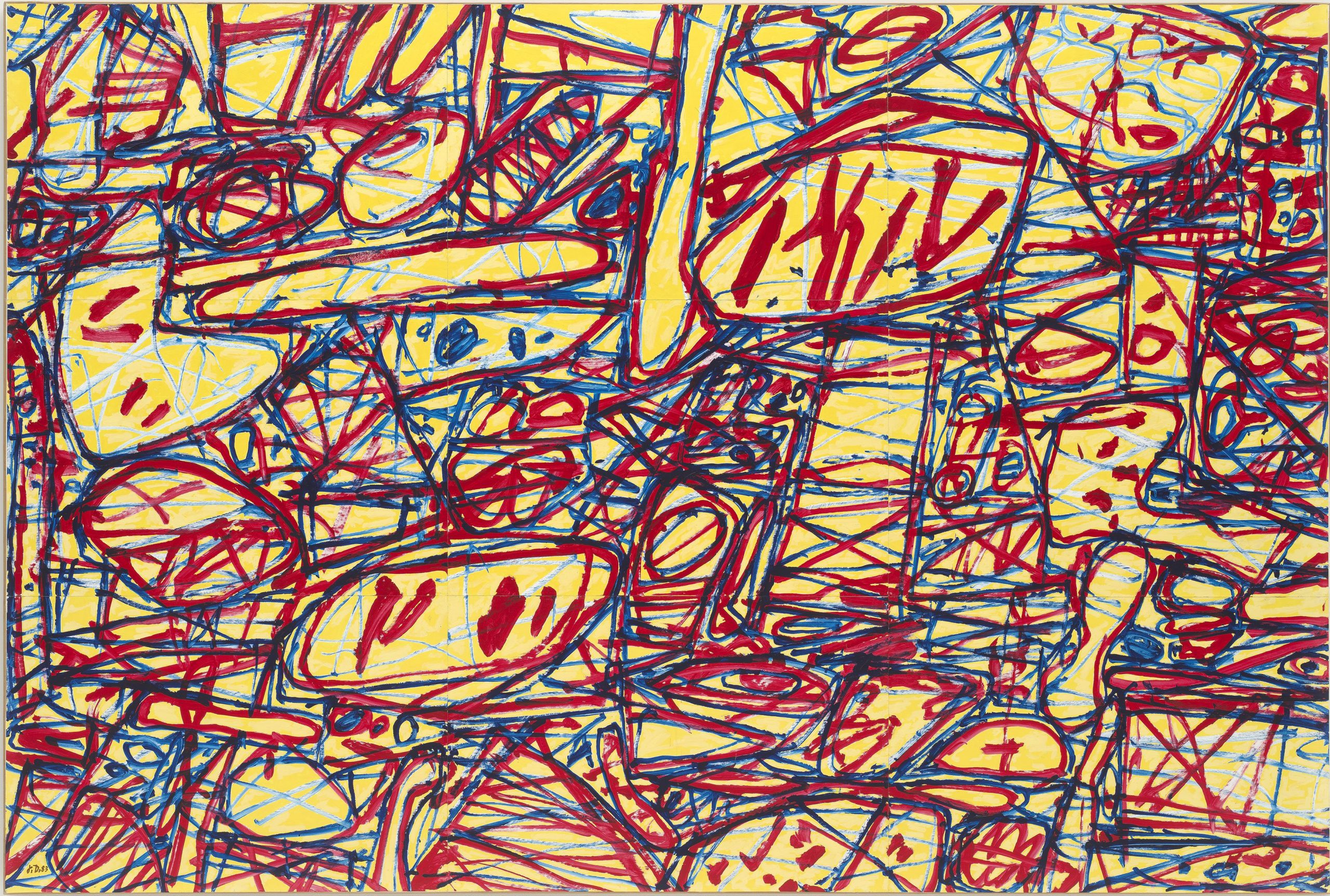

In July 1945, Dubuffet had visited psychiatric patients in Switzerland and viewed works by patients from the Bel-Air psychiatric clinic at Geneva’s Ethnography Museum. Their impulsive approach to art making had a profound influence on his idea of Art Brut (‘raw’ or ‘crude’ art in literal translation). His more abstract works reflect this unshackling. Their shapes and contours trace the mind’s undulations, psychic life’s subterranean textures, and the unevenness and earthy disorder of a truly liberated creative process.

His landscapes, including pieces from the 1950s such as La butte aux vision (The Knoll of Visions) and Substance d’astre (Substance of Stars), show the artist’s thick impasto oil style, a layering he mirrored elsewhere using a thick paste of zinc oxide mixed with varnish.

His Hourloupe works, which began in 1962, are some of Dubuffet’s most recognisable to contemporary audiences, in part due to their notable influence on the work Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. In the period immediately after D-Day and the liberation of Paris, Dubuffet would walk the city streets, observing graffiti and a jaded population. Apparitions of stray faces and alphabets appear and disappear as viewers circle the Hourloupe works, a jumbled interplay of vision and imagination.

Dubuffet invites us to follow in his footsteps, discarding art historical debris and replacing it with his strange creations. “I am a tourist of a very special kind’, he wrote in 1958. “What is picturesque disturbs me. It is where the picturesque is absent that I am in a state of constant amazement.”

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant

Jean Dubuffet, Ardent Celebration, Guggenheim Bilbao, until 21 August

All images © Jean Dubuffet, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022