Eloise Hendy visits Vivien Zhang’s studio and discovers Pringles, trompe l’oeil, lottery balls and butterflies. Together they decode these references as they pertain to Zheng’s wider practice.

Walking into Vivien Zhang’s East London studio feels a little bit like stepping directly into someone’s brain. There’s also an undeniable whiff of that It’s Always Sunny meme, where Charlie Day gestures wildly at his conspiracy wall. This is not to suggest that Zhang herself is a conspiracy theorist – more that every surface bears evidence of singular creative thinking, decipherable only to the mind that spawned it. Looking around the room – at the sheets of paper taped to the walls, the folders spilling over desks, and the rainbows of dried paint crusting in crumpled plastic pots, on tables and all over the floor – I have the impression of being held in the eye of a storm: a fleeting moment of calm before a whirl of experimental investigation begins to whip up once again.

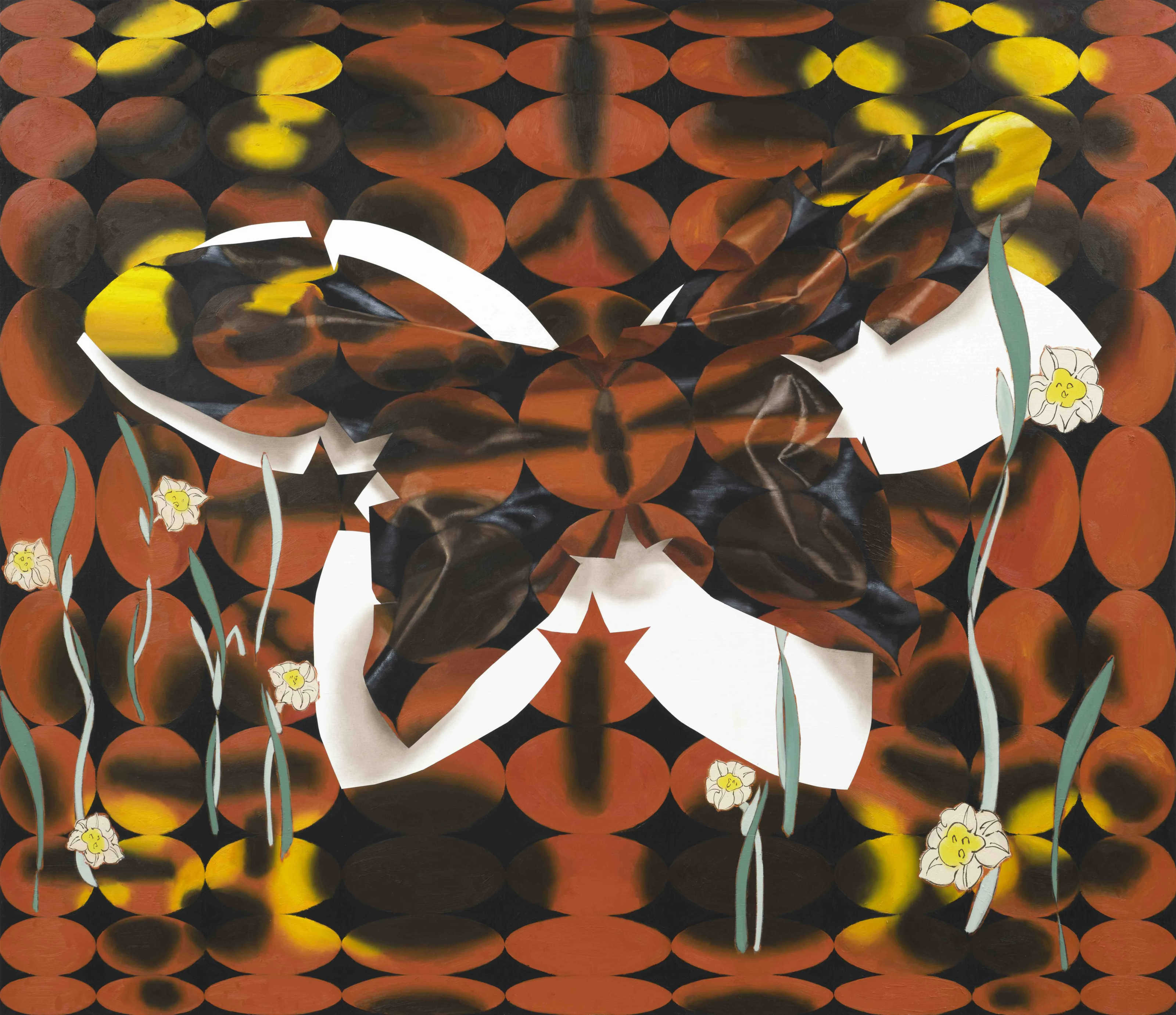

This cyclone effect feels fitting, given the density and near-dizzying dynamism of Zhang’s works. Yet, at the same time, I can imagine some viewers of her paintings would expect a very different scene – perhaps more reminiscent of a hard drive than a churning weather system. This is because Zhang’s work often gets classified under the rubric of “digital art”. The classification isn’t surprising, given Zhang’s uncanny rendering of blur and pixelation in many of her paintings. Yet, it is also an incomplete one. Indeed, Zhang’s new solo exhibition at Pilar Corrias, Flat Earth, proves that the beauty of her work is that it is various and multiple; that it cannot be so easily pinned down. As the gallery suggests, her paintings “straddle the tension between the perfection of a digital image and the chance of painterly composition”. In other words, they are works of both control and coincidence; order and chaos.

Zhang’s studio is long – a rectangle with a boxy area at one end (“ideally, that would be a viewing space,” Zhang tells me, “but I never have it organised enough for a viewing space”). On one side of this nodule-like space, a door opens into a small courtyard (“people have said I don’t use that enough, because I don’t smoke,” Zhang laughs). Large paintings – some still in-process – are propped up in stacks, or hung in clusters on the walls (“I think it’s really nice to have them sitting together,” Zhang says, “so they can talk to each other already in the studio”). Surrounding everything else are drawings and diagrams of all descriptions. Butterflies teem in one zone, while in another old maps and anatomical drawings form a heady dialogue. In one image, a figure raises their arm to reveal a cut-a-way in their flesh, showing the layers of muscle within. And… is that a drawing of Pringles pinned up on one wall?

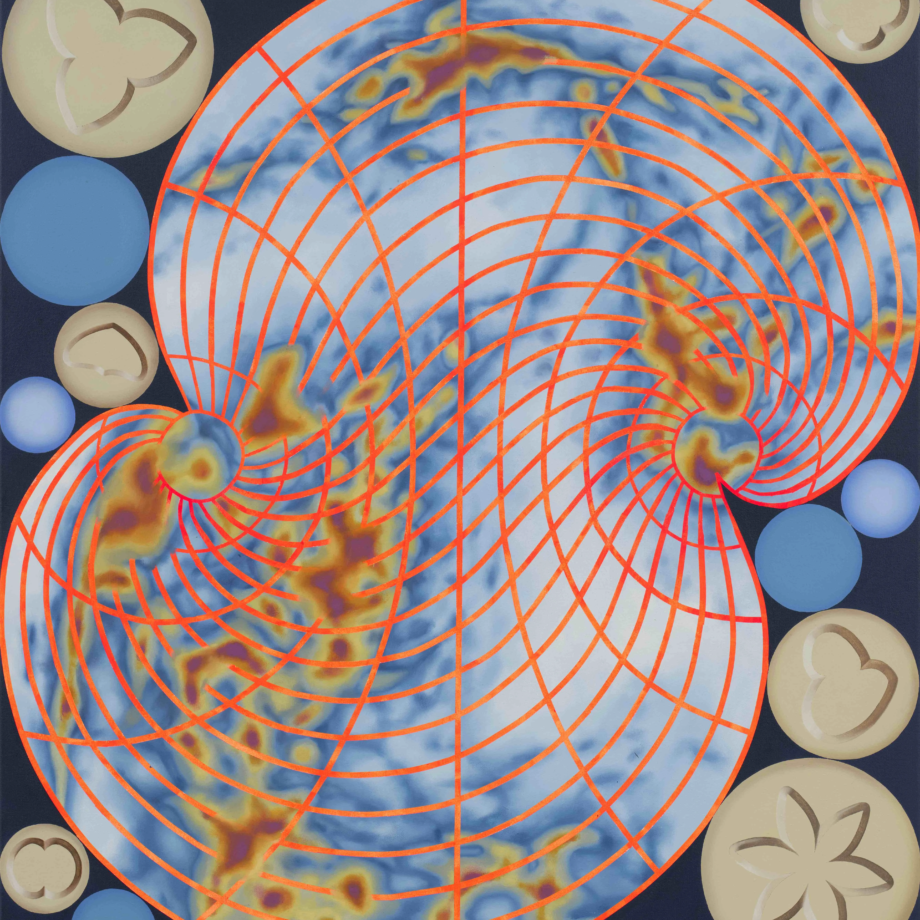

“A friend came to my studio and she was like, ‘are you looking at Pringles Vivien?’,” Zhang laughs, catching my eye lingering slightly on the crisp diagram. She’s not laughing if off though – she is thinking about Pringles, and how they relate to maps, and her own creative practice. “How they stack up together, and they’re the most stable, but you wouldn’t think about that stack as curved,” she muses. “I think the shape of the Pringle is also quite like a Photoshop layer, where you’re dragging something or warping something,” she adds. “I think that informs a lot of the aesthetic decisions in the work,” Zhang says. What she means, is how she works to create space. “These layers – not the Pringles,” she laughs, “but the painting – the flat layers – if a mark is travelling in one direction, and if the shade is in another direction, it can create a sense of space, within flatness”. Suddenly the Pringles make complete sense. Like grated cheese, their curved form is supposed to increase their surface area, giving each crisp more flavour. Zhang is seeking the visual equivalent. She’s attempting to actually increase her canvases’ surface area: to open them up.

This, I realise, is also the logic behind the anatomical drawing’s peeled back skin, and the butterfly cut-outs Zhang has wrinkled and curled before sticking them to the wall, so she can copy their folds on the canvas, to make it look like the painting itself is unfurling. “That’s going back to basic painting,” Zhang says. “Thinking about illusion, trompe l’oeil and how to create space on a flat surface”. Considering how she manages to make the connection between Pringles and trompe l’oeil feel seamless, I think again of the generative tension in her work between traditional painterly techniques and contemporary digital effects. “I think it might come from me being greedy,” Zhang laughs. “The works have to be driven by an idea, right? Something I’m interested in,” she continues. “Like, when I’m in the studio I’m listening to podcasts about things not related to painting. I love Ben Luke’s podcast,” she says, referring to The Art Newspaper’s The Week in Art, “but I can’t listen to them all the time because it makes me really anxious. I’m like, ‘oh no, I’m not painting like Jacqueline Humphries’.” Zhang rolls her eyes, in an endearingly self-deprecating way. “So then my other go-tos are tech podcasts, internet podcasts, things about internet phenomenon. I think that translates,” she notes. “They drive the idea, but then at the end of the day, it’s still about painting”. When she’s finishing a work her attention shifts, and she can only paint to music “without any words that I can decipher, then I can really return to the texture, the surfaces”.

Still though, her ideas are clearly an animating force – the atmospheric pressure causing Zhang’s creative cyclone. For the Pilar Corrias show, Zhang has created an array of new works, which, she says, are “all about imitation and classification, and how we are unable to pinpoint the things around us. Everything’s in flux,” she continues, “we really should reevaluate things around us all the time.” In a sense this is a continuation of preoccupations Zhang has had for a while. “I’ve been looking at map projections from past centuries,” she says, for instance. Yet, for these new paintings she has honed in on one in particular: the Waterman “Butterfly” World Map, which unfolds the globe into eight octants, resembling a butterfly. “The map is like the skin to our globe,” Zhang says, “and I thought about the skin of the butterfly, and how they sit together, and my relationship to layering, or the surface of painting”. In Zhang’s mind, it’s all connected; “I think about the skin, the canvas skin a lot,” she muses. Even the language she uses around her work reflects this concern. “I don’t like to use the word ‘series’,” Zhang tells me at one point, “because I feel like it makes it seem like it’s an end point. I would just say ‘body,’ because ‘body’ seems organic – more fluid and flexible”.

This new body is ‘organic’ in other ways too. In one set of paintings, Zhang combines the butterfly map with real butterflies. “I want the organic species to marry the maps,” she says. “So each of them are based on particular butterflies.” There’s the monarch butterfly, “which is a migratory butterfly,” she explains. “Then from that, I found these butterflies which have this property of mimicking each other to avoid predators. So, if one is poisonous, another one might imitate his patterns so you avoid it”. Here then, is another layer of Zhang’s work, which also connects out to her broad concerns with imitation and classification. “There are different kinds of evolution,” she tells me. “One is, ‘I will pretend to be you’. The other one is, ‘we will both evolve so that we both share similar traits’.”

There’s another recurring organic element in Zhang’s paintings: a plant with flame-coloured petals, spilling with black seeds. “I came across them during COVID when my mom was on one of her hikes in Hong Kong,” Zhang explains. “They’re edible, but they only bloom in May and June in southern China, so they’re, like, really niche.” Zhang smiles, picking up a cut-out from one of her busy desks. “That’s what they look like in real life,” she says, awestruck. “It tastes like chestnuts, apparently. I’ve still never seen them”. Aside from their vivid, erotic allure, these plants interested Zhang for another reason. “In the Chinese name, this is called the fake version of another similar plant, which has one seed”. This gluttonous, seed-greedy plant is a bad mimic, in other words – in linguistic classification at least. “I realised, looking at this, there’s a whole group of plants in English that’s called ‘pseudo’ something,” Zhang continues. What piqued her interest was the limitation these plants represent – “our limitation in language, and how we can’t give them new names,” as she puts it. “I felt like that limitation is just quite bizarre, really bizarre. Why is one called the fake version of another one? Why is one authentic? Why is one not?”

At the heart of all this fakery and mimicry is a tension between certainty and uncertainty, Zhang suggests. “That also goes back to classification, right? If you have something ‘certain’, it’s always, I think, going to break down when we gain more knowledge of the world, and how we make hierarchies of different things.” From one flap of a butterfly’s wing, we have now arrived in another realm. “I really love 1984,” Zhang says, and it takes me a moment to catch up to where her mind has now landed. “If you don’t have a word for emotion, do you still feel that emotion? If you don’t have a word for a plant, does it still exist? If we didn’t have derogatory terms for race and gender, do these ideas still exist?”

Throughout our conversation, I can feel my mind whirring at Zhang’s pace, trying to crack her codes. “I love the word code!,” Zhang exclaims. “Code is definitely a big word when I think about my work”. It perhaps makes sense to describe her work as ‘cerebral’ then, even if this seems a little strange when looking at her beguilingly rich, vibrant paintings. “It’s quite funny,” Zhang says, seeming to agree with a thought I haven’t yet uttered. “I don’t think about the image that much. I say “read” the painting, not “look at” the painting”. Even compositionally, she continues, “I’m not thinking about making a pretty picture, I’m thinking about balance or tension.” She gestures to one painting, which is scattered with warped circles and different coloured seeds. “I wanted to have some smaller things around,” Zhang explains. “You know, if you’re reading something, you have a big chunk of paragraph, and then you have punctuation around”. Later, she refers to different groups of paintings in this “body” as having “a different language”.

But “reading” is just one coda. “For the first time I’m using really complicated mathematical numbers,” Zhang says, pointing to another, unfinished painting, which is set out on a grid system. “There’s a group of numbers called lucky numbers, there’s a group of numbers called abundant numbers,” Zhang reels. “This one, I’m using primary numbers. It’s a formula,” she explains: “a really bizarre rule”. Zhang is, essentially, painting by numbers – letting the formula dictate where her repeated forms fall. “It fascinates me because you come up with a result, which is arbitrary, but also not arbitrary because it’s got this logic,” she notes. “There is a system, so I kind of give away my agency in this way.” Yet, there is an element of fakery here too. “It’s false because I am choosing,” Zhang stresses. “I’m setting up the system, but I also don’t know what it looks like in the end.” Control and coincidence in other words; order and chaos theory.

“I was listening to this podcast about lotteries, and how the most random is still drawing the ball,” Zhang tells me. “Even if you input a formula into a computer, it’s always gonna be formulated, right? So it’s still the most random – that physical drawing of a ball”. Like the Pringles, this seems to gesture outwards to her entire practice, speaking to her approach to digital technology – how it assists and inspires her, but how, “at the end of the day, it is still about painting”. “If artificial intelligence can make art,” Zhang muses at one point, turning over another kind of ‘imitation’ in her mind, “I think the question is, why do we still value the work made by the hand? Where is the value? Is it made by this specific person? Or is it just a picture that you’re looking at?” In a sense, the lottery balls provide an answer: the value of human action and agency is found in randomness. “When do I step in,” Zhang voices. “When do I leave? In a lot of the work there’s a very precise logic, but then sometimes I’m like ‘no, I just have to paint a blue seed’.”

Like her new ‘body’ of work then, Zhang is also reevaluating things all the time. In flux. “Sometimes imposter syndrome creeps up,” she admits. “I’m trying to find out something, but why would somebody else come along this journey with me?” This is the plight of every creative person, Zhang believes. “There’s always a journey they’re going on, but they have to bring an audience,” she says. “There’s that negotiation: how much do you give to the audience? How much do you bring them, leave them? And how much is more like, ‘look at me, me, me’.” Zhang grins, and I can see another line of thought settle. “I also wonder if it’s a sign of our times, our generation – we have so much access to so many different things that we can’t just corner on one thing,” she says. “With search engines as powerful as Google, I’ve always felt, are we a generation that knows how to access knowledge, but doesn’t retain the knowledge? Is that a skill that we should value or not?”

I have my own question: if this voracious, sweeping attitude to information is the sign of a generation – our generation – is Zhang the voice of it? Mapping her thought process, I have the impression that she herself has become a search engine of sorts: always questioning, probing, seeking out new avenues of knowledge. “Without sounding too depressing,” Zhang continues, with another, slightly sheepish grin, “but it makes me think about more existential questions, like does one live to enjoy life, or does one live to work and further oneself? I think it’s two philosophies, right? You know, 80, 90 years you have on earth? Are you there to make your life as easy as possible? Or is there something you’re striving to do more?”

Pringles, trompe l’oeil, lottery balls and the flap of a butterfly’s wing. In Zhang’s studio, turning over questions of life and death, it is easy to forget that, at just 33, Zhang is still right at the beginning. “A collector came for a studio visit and she was like, ‘when did you find your voice?’,” Zhang tells me. “But I’m still finding my voice. My voice is evolving.”

Written by Eloise Hendy