In 2020, at the height of lockdown, Alanis Obomsawin did something that she never thought she would: she went through her archives. It was an enormous task, with more than 50 years’ worth of recordings stashed in her Montreal home. “I started in the morning, and I cried all day,” she says. “Just listening to these people who were talking about their lives. It was so moving.”

Obomsawin has dedicated her career to other people’s stories. Across six decades, the Abenaki artist has made more than 50 films, offering a compelling portrait of indigenous Canadian history, using the voices of those who lived through it.

Her huge archive is the by-product of years of listening to communities who often go ignored. “The most important people are the people who are in those documents,” Obomsawin says. “It’s not ‘my film’ as such.”

Her extraordinary career is the subject of a new retrospective at Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. The Children Have To Hear Another Story is a chronological survey, which combines key films (documentaries, experimental shorts and television works) with musical recordings, textiles, prints and drawings.

Archive interviews and personal correspondence allow the artist to tell her own story, as we follow Obomsawin’s journey from young performer to outspoken activist and public figure. Visiting the exhibition provides a taste of how Obomsawin must have felt when confronting the volume of her archive: it’s emotional, absorbing, and at times overwhelming.

The exhibition actively engages with the principles of decolonisation and collaboration which underscore Obomsawin’s work. “Alanis’s career is powerful evidence that sustained hard work, using whatever resources are available at the time, and refusing to be discouraged by resistance, leads to dramatic social change,” says co-curator Richard Hill.

“I started in the morning, and I cried all day. Just listening to these people who were talking about their lives. It was so moving”

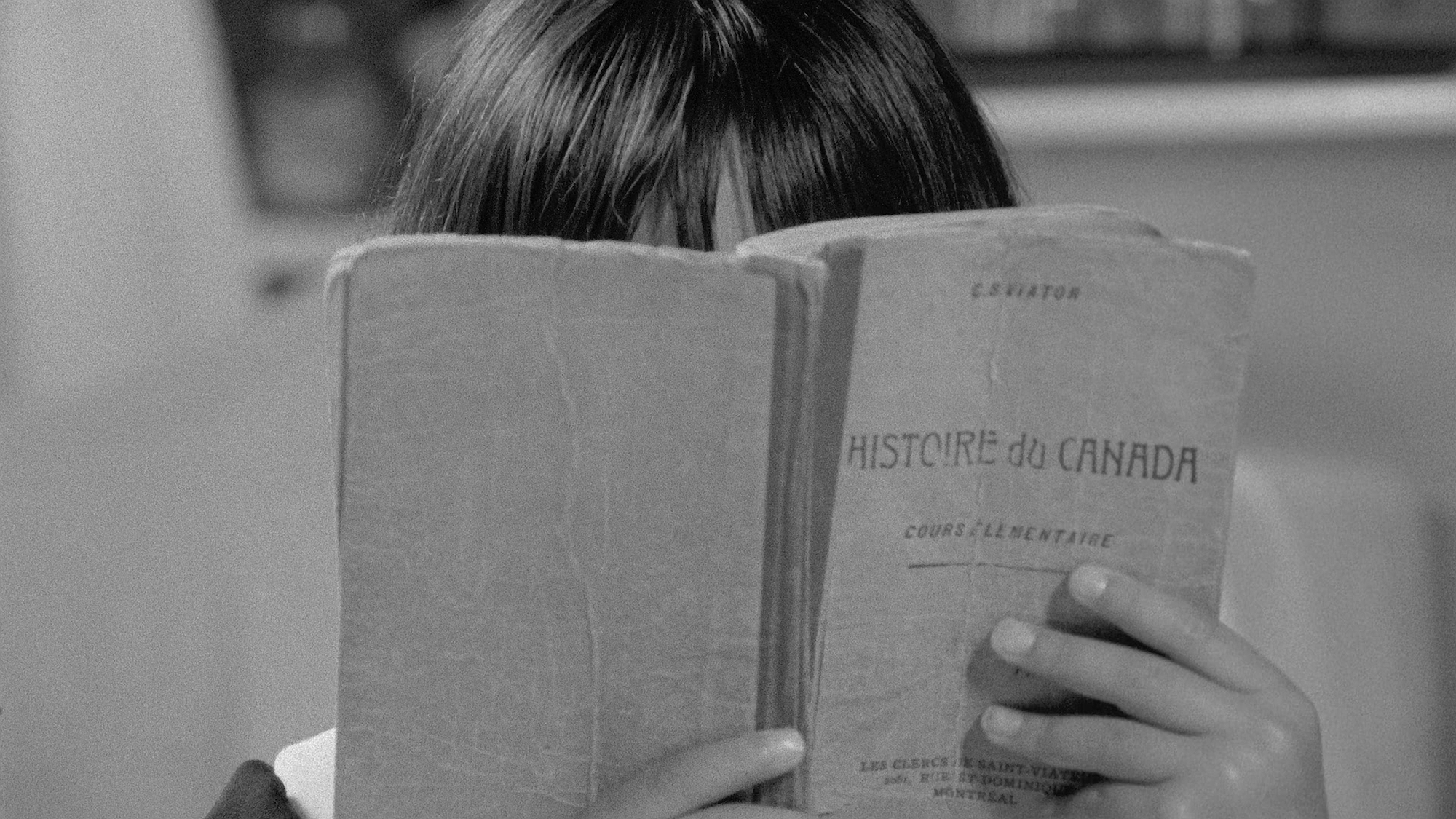

Obomsawin’s filmmaking practice challenges assumptions and centres marginalised voices. These achievements are even more remarkable when you consider the context. In 1932, the year she was born, indigenous people in Canada were forced to renounce their ‘Indian Status’ in order to vote. Until the 1960s, children were routinely sent to church-run residential schools which explicitly aimed to eradicate indigenous languages and traditions. Although Obomsawin did not attend a residential school, her creative practice was shaped by this climate.

As a child, she moved with her family from the Abenaki reserve of Odanak, Quebec to the city of Trois-Rivières. There she was the only indigenous child in her class and the racism she experienced, from both classmates and teachers, led Obomsawin to resolve to “tell another story”.

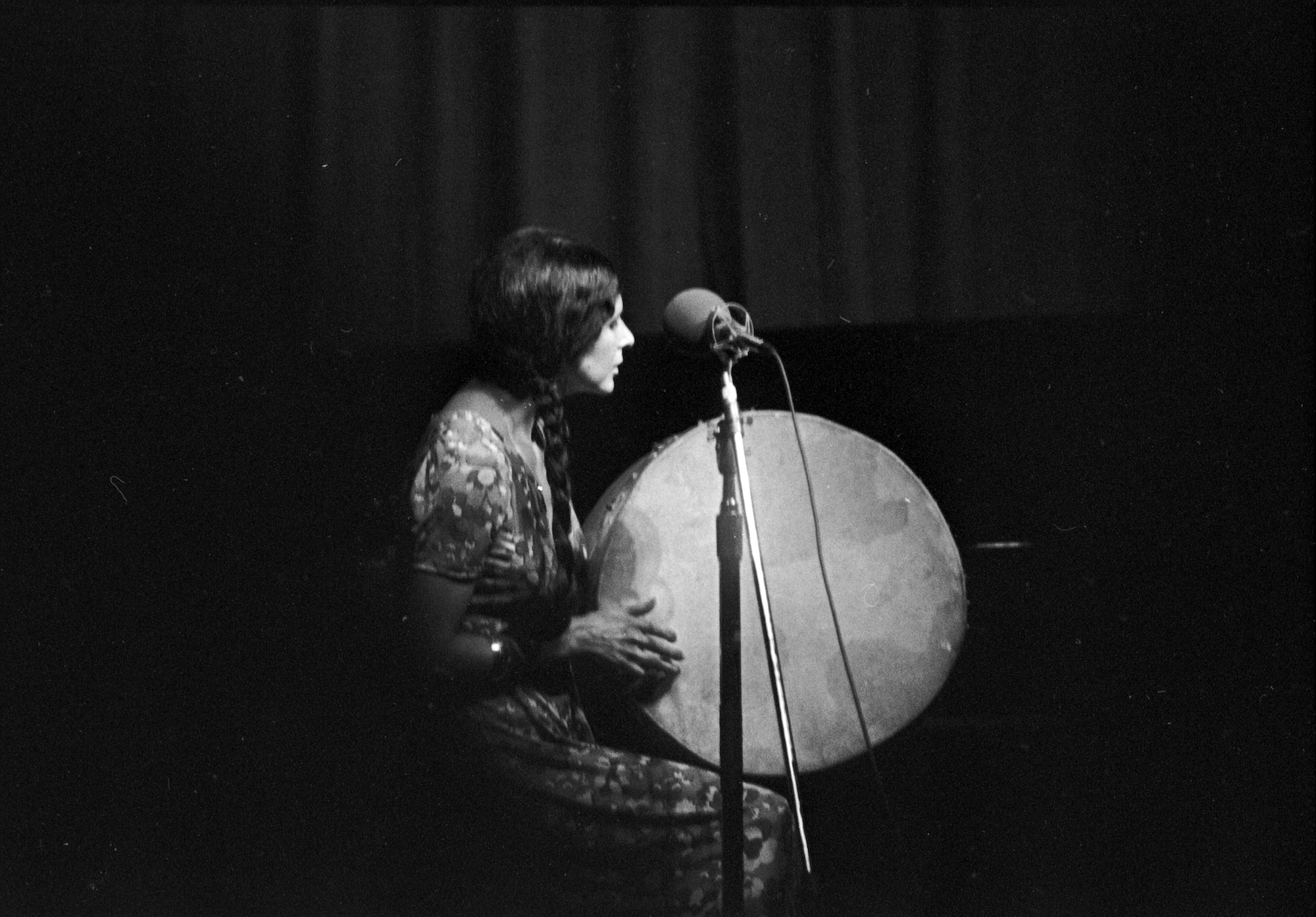

In her teens, Obomsawin began performing in local schools, sharing the traditional stories and songs she had been taught by her relatives. By the 1960s, she had become well known in Canada as a performer and public intellectual, playing alongside Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell at folk festivals and appearing on television to discuss indigenous issues.

Clips from these appearances open the HKW exhibition and provide an insight into the attitudes of the time. Obomsawin appears on a succession of chat shows, one moment drumming and singing, the next debating the merits of non-violent resistance with a member of the Black Panther group or arguing about the politics of assimilation.

“The most important people are the people who are in those documents. It’s not ‘my film’ as such”

Eventually, Obomsawin’s long-held affinity with young people led her to filmmaking. After an unsatisfying stint working as an indigenous consultant for Canada’s Film Board, she began to teach herself to use a camera. In 1971, she made her first short film, Christmas at Moose Factory, composed almost entirely of the voices, stories and artwork of young Cree children whom Obomsawin had met while visiting residential schools.

“I used to tell them stories at night before they slept and got very close to the children,” she recounts, laughing at the memory. “They knew me so well, that I said, ‘It’s your turn to tell me stories’.” Obomsawin’s recordings of the children became the warm, witty and subversive Moose Factory. By inviting us to see the world through the children’s eyes, Obomsawin makes room for voices that were almost entirely silent in the culture of the time, a quietly radical political statement.

Moose Factory provides the blueprint for Obomsawin’s working method. Her films extend oral traditions, creating space for her subjects to pass on stories in their own words. That radical listening is reflected in the texture of her filmmaking. Contrasting forms, animation, archive photography, re-enactments, interviews and fantasy sequences are layered to reflect the diversity of the voices that Obomsawin captures.

Her first feature, Mother of Many Children (1977) blends styles to offer a glimpse into the lives of women and girls across the country, from a new-born baby girl to a 100-year-old grandmother, from an incarcerated woman to a Harvard undergraduate. The result is a transfixing collage, which challenges stereotypes by gesturing towards the infinite variety of indigenous female experiences.

“There’s a lot of effort to try and make a place for our people, and we feel it. Before it was very silent, and no one listened to us. Now it’s different”

Obomsawin also reacted to unfolding history. In 1990, she was driving to work when the radio reported a shootout at the Kanehsatake reserve in Quebec, where members of the Kanien’kéhaka Nation were protesting as part of a land dispute. She drove there and began to film, ending up spending 78 days behind Kanien’kéhaka barricades, recording a tense confrontation between the army, protesters and police.

The Oka crisis, as this standoff became known, was a defining incident in contemporary Canadian history, exposing long-held tensions between indigenous communities and the state. Obomsawin made four films about the crisis, including Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, which has become her best-known work.

Kanehsatake is an extraordinary piece of guerrilla filmmaking. “It was really not easy,” Obomsawin says. “Behind the barricades, we were only allowed two people. So, I was doing the sound and I had a cameraperson and that’s it. And then the cameraperson would leave because they’d say ‘There’s gonna be a massacre here, I’m leaving, I’m not staying here.’”

Alanis Obomsawin, When All the Leaves Are Gone (film still), 2010. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada

The film offers an alternative narrative to the state’s official account, presenting the conflict as a consequence of centuries of colonial oppression, but Canada’s national broadcaster (CBC) initially refused to approve Obomsawin’s edit. Instead she took Kanehsatake to the UK where it premiered on Channel 4 and screened theatrically to standing ovations. Eventually CBC conceded and screened Obomsawin’s cut. Today the film is widely regarded as a landmark in indigenous cinema.

Over recent decades, public pressure has forced the Canadian government to acknowledge the cultural genocide of the residential school system, while indigenous-led grassroots movements have begun to shape conversations about decolonisation. “It’s a welcome moment, people feel there’s a place for them, they don’t feel intimidated anymore,” says Obomsawin. “There’s a lot of effort from the government, from everyone, to try and make a place for our people, and we feel it. Before it was very silent, and no one listened to us. Now it’s different.”

At 89 years old, Obomsawin is still working. She is currently editing eight films simultaneously, made using the archive footage that she revisited during lockdown. When she looks back at her completed films, Obomsawin sees stories,those that she managed to capture and those that were left behind.

Obomsawin remains full of energy and purpose. It’s impossible to imagine her stopping. As long as there’s a story to be told, she’ll be there with her tape recorder, still listening.

is a freelance writer, curator and producer. She is co-founder of the feminist film collective Invisible Women

Alanis Obomsawin, The Children Have to Hear Another Story, is at Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt (HKW) in Berlin, until 18 April