What should the banner for this part of Los Angeles read? “Industrial”, for starters. I’d say this area has that creeping, transitional feel of an American frontage road: a likely target for future gentrification, but quiet for the moment. If I wanted to get fancy, I’d say it’s “liminal”.

South-east of downtown, Walead Beshty’s studio is one of several unornamented warehouse boxes with its windows shuttered, bordering a wide avenue alongside plein air parking lots, the occasional single-family home, razor wire fences, taco stands and the triumphal Golden Arches. LA’s answer to the Champs-Élysées.

I shouldn’t act so surprised when I walk inside the industrial building and essentially find myself in a gallery: the work process is beautifully displayed here, white walls and all. It’s striking to see artwork in its earliest stages, like the piles of Mexican newspapers Beshty has spread out on his tables (“Dead bodies on the cover, usually a car accident on the back, and naked women throughout,” he explains. “I had this idea to import these papers for the Basel Fair, and leave them at people’s hotel room doors”).

It’s equally impressive to see finished works, though, removed from their foster homes of books and museum spaces, and placed back in their original test tube. A number of Beshty’s pieces, like some of his Selected Works (1998/2008–), hang on the studio walls with exceptional presence.

An ongoing project, Selected Works is “comprised of works that I decided I don’t want to show,” the artist says. “I shred them and reconstitute them into these sort of flat panels. I make them when enough material accumulates. Each one is made of several hundred works.”

“I like to think of these objects in the studio being liberated, allowed to float freely between meanings and associations”

Of course, it’s one thing to transform (or conceal) several hundred discarded works into a single object and hang it in a place where, potentially, several hundred or more strangers will see it, many of them unaware what exactly they’re looking at. It’s another to have the work confront other works that might meet the same fate, like evaporated air confronting the puddle it came from. Or, more relevant, like a person who’s just passed border control, looking back at the rules and realities left on one side of a country’s boundary line. Resounding but “invisible transformations”, as he calls them, are a recurring atmosphere in Beshty’s works, including his famous Travel Pictures (2006/2008) and FedEx Boxes (2007–).

Sitting across from each other at a work table, Beshty and I have a long, at times intense, conversation. Beshty hardly needs prompting to talk about art and its place within politics, society and international airspace. Occasionally, he stops me and asks, “what do you mean with that question?” Later, we come back to our discussion in a series of emails, with Beshty adding on, filling in and footnoting some of the points he’d made before. Like many of his works, our resulting conversation is a composite that’s careful to note its references and intent on clear exposition of the unexplainable. Beshty offers his thoughts, but is careful to note his relationship to them. “I’m not interested in making judgements,” he tells me. “Everyone makes judgements. Just because artists have the ability to broadcast theirs doesn’t mean they’re interesting.”

What are those “blueprints” covering the studio wall behind you?

That’s the beginning of a new work for the Barbican, which will be made of 12,000 cyanotypes – one of the earliest photographic processes. It’s a light-sensitive material that can be spread on any cellulose, from wood to paper. The piece is called A Partial Disassembling of an Invention without a Future: Helter-Skelter and Random Notes in which the Pulleys and Cogwheels Are Lying around at Random All over the Workbench.

That’s a mouthful.

It’s taken from a lecture by [artist/filmmaker/theoretician] Hollis Frampton, in which he discusses how meaning is opened up when a thing’s currency has passed. He was defending cinema during the advent of video. His title is actually based on a Lumière brothers’ quote, where they referred to cinema as an “invention without any future”.

Frampton points to how meaning is freed up through the movement of things into and out of currency and the cultural imagination, that dormant things have a great deal of potential.

“Everyone makes judgements. Just because artists have the ability to broadcast theirs doesn’t mean they’re interesting”

Are “dormant things” part of this artwork?

Yes, it’s all photograms of objects from around the studio – things that are used up, broken and exhausted in the process of production, which are then imaged on cellulose-based waste materials like notes, packaging, envelopes,letters, bank statements, parking tickets, invites, drafts of essays I might be working on. Everything that takes place here or passes through here.

I have to admit, the project is a bit daunting. It will take at least a year to make, and requires work every day. It’s about coming to terms with all the byproducts of making my work. I always try to deal with the detritus produced from my practice. I dislike having to say, “this is outside” [the artwork]. It seems lazy to do so. I don’t want to arbitrarily exclude anything. Besides, all of these things affect how the work is understood. They’re the side effects of aesthetic forms – they’re forms made in the margin of other forms.

When you cut a form out of a sheet of copper, for instance, you still have a sheet left over. When I first made the copper tables, the left-over felt like a loose end I needed to return to, which is what those are [Beshty points to his work Copper Remnant (Table: designed by unknown, date unknown; Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, September 8th, 2011), 2012]. What does that remnant mean? I think it’s as important as the object that was cut out of it. They’re complementary: both were needed for the thing to exist. So I work with that form, figure out how to adapt to it, account for it, understand how it could be drawn forward in aesthetic terms. I never want to say “this is out of bounds” and ‘this is in bounds’. Everything should be in bounds.

How does that relate back to Frampton’s lecture?

Frampton’s idea is that meaning is opened up once a thing’s time has passed. Then that thing opens up to a multitude of other potential meanings. I was initially intrigued by his image of pulleys and cogwheels scattered at random all over the workbench, like the Dürer print Melancholia (1514), which shows the angel with tools in disuse. When Walter Benjamin developed the idea of the allegorical as ruin – as a constellation of fragments, comprised of things that no longer have any function – he pointed to that Dürer print.

That makes me think of something else Benjamin wrote, and I’m paraphrasing here: “collecting is an evocation of a utopian world where objects are liberated from the drudgery of being useful.” I like to think of these objects in the studio being liberated, allowed to float freely between meanings and associations. It’s a piece that tells the story of its own making by describing the entire productive life of the studio: Every bit of debris produced, every note, every false start, every abandoned idea.

I like that there’s an almost infinite regress into the details of the work and that it’s so materially transparent that it becomes opaque and overwhelms the viewer with relevant information.

What do you mean it’s “materially transparent”?

The studio debris making up the cyanotypes contains private correspondences, interactions with the museum, and so on. Every detail – personal, professional, everything – is actually in the work itself, and what’s more, it is what it is. It’s debris, it depicts debris; it’s a work, it depicts making a work.

But the “meaning” of the artwork isn’t transparent.

Meaning is always a collective activity. Each object is informed by its movement through the world and its contact with people. In that sense, meaning is always cumulative and contingent. I can’t control how things acquire meaning. I try to only think about what a work is, not what it means.

You don’t have a metaphor you’d like viewers to take away from an artwork?

Metaphor and symbolism propose to stop the development of meaning by declaring it a finite thing and saying “this means that.” It’s wholly undemocratic. So, no, I try to stick to the material conditions of the work: how it’s produced or the logic of the work and the production of it. In that way, I try to be transparent. Power tends to conceal the origins of things, making them seem exotic or originary, as though they just arrived through some sort of divine will. I try to do things in obvious and simple ways. I’m conscious not to transgress upon the autonomy of individual viewers and take away from their role in the production of meaning.

What would your transgression be?

Trying to fix a certain type of metaphor to an artwork. I think that verges on the fascistic. To say that something stands in for something else – and impose that – cuts against the most compelling attributes of art objects. Fascist aesthetics tend to dictate meaning and treat metaphor as concrete, reifying the intangible or soft associations, and turning the social and ephemeral into the concrete. I think it also leads to phantasmagoria and delusion, where all that is solid melts into air, and vice versa.

There are problematic questions of power wrapped up in all of this. If I tried to dictate metaphoric associations for what I’m doing, I would be relying on some vehicle outside of the work to assert it, like a wall label or a press release. There would need to be some arbitrary voice of authority to impose such a reading. Beyond that, I find that an attempt to stop the open interplay of meaning and restrict the associations viewers can make is sinister at worst, and uninteresting at best.

Why is it important for you that people see “process” in your work – I mean, the detritus that goes into it, the time it takes to create?

I’m not really interested in emphasizing process, it’s really a matter of the process being available and not hidden. Most of the processes I use are really simple, which is important because I don’t want them to be so intricate or fetishized that they’re the focus of attention. Putting the process out there is a way to get past it, to make it just another dumb fact. So, I want the procedure to be simple enough that it’s mundane and easy to convey, and so that little time is spent relating that information.

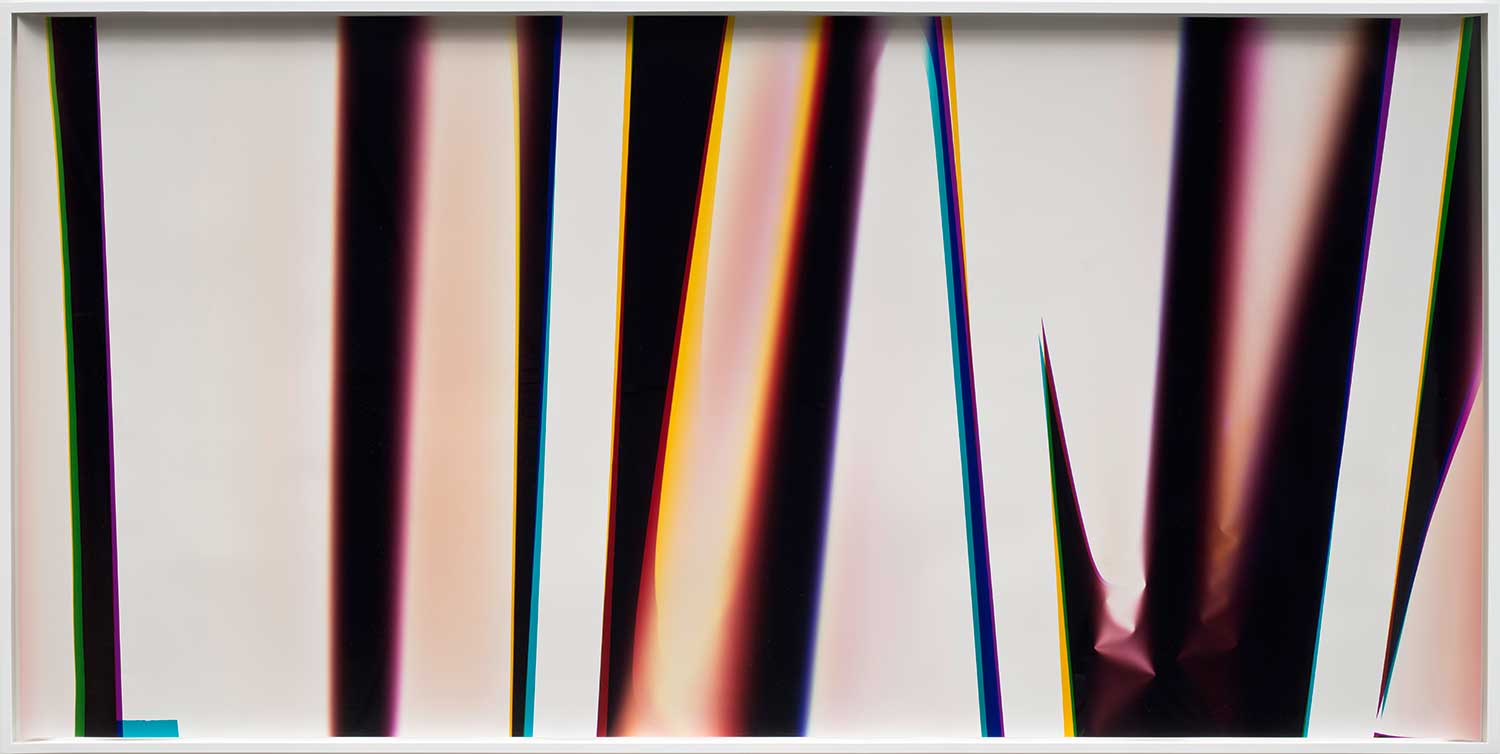

![Transparency (Negative) [Kodak Portra 160NC Em. No. 3161: November 28–30, 2010 LAX/MIA MIA/LAX], 2011, Epson Ultrachrome K3 archival ink jet print on Museo Silver Rag Paper, 132.7 x 172.7 cm. Photo: Brian Forrest, courtesy of the artist; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/WB88310.jpg)

What’s mundane about a work made of 12,000 cyanotypes?

Well, anyone can make a photogram like the one over there; it wouldn’t be identical to what I’ve made, but similar enough. I mean, it’s super easy. Most of these things [gestures around studio], anybody could do easily, as opposed to, say, a Hollywood movie. You go see a film and most of the time you’re, like, “How the hell did they do that?” A movie is really premised on the awe produced by the economies of scale. A comedian named John Mulaney made a joke to the effect that he would pay ten dollars just to see 100 million dollars in a hotel room – actually making a movie with that money is unnecessary. When I see a Hollywood blockbuster, I often think, “I’m just watching a visual abstraction of money.” Really, I’m just watching money – the sublimity of accumulated capital. Many cultural objects seem that way: evidence of the movement of money, declarations of power. Like when dictators install portraits of themselves throughout a country, it’s capital depicting itself to declare its ubiquity.

Do you ever get that feeling looking at art?

Sometimes art is like that, where the scale and production level reaches the absurd for no apparent reason. Art can’t really compete on that level – there’s not quite enough money in it yet for that sort of gesture to be effective. But art can serve to mythologize the decisions of the artist, which causes a similar effect.

“Art critics often lament the academic or theoretical language that surrounds art, claiming it’s “elitist”, which I find perverse, disingenuous and condescending”

Does art mythologize the artist’s decisions, or is it the art critics?

Art itself has the potential to democratize aesthetics and reimagine aesthetic production as communal, available and non-hierarchical. I like the idea of demystifying aesthetics by communicating that we can all make aesthetic objects; it’s not simply for those with capital or power.

That said, art critics often lament the academic or theoretical language that surrounds art, claiming it’s “elitist”, which I find perverse, disingenuous and condescending. It assumes a public is stupid and incapable of relating to complexity. I don’t buy that in order for people to have access to artwork, the discussion of it should be simplistic. I mean, look at your computer: Only a very small minority of people who own a computer actually know how to program one, and even fewer could put one together start to finish. Does that mean that computer scientists shouldn’t use technical language? That people should construct computers with only as much complexity as everyone could understand? Does it mean I need to think of my computer like a computer programmer or engineer to be able to use it intelligently? No. One can have a very thoughtful relationship to an object without having command over the technical language used by those who produce it.

The logical extension of the “populist argument” is an evaluation of exhibitions just by the number of bodies they bring through museum doors. You would perpetually have Tim Burton and motorcycle exhibitions. You wouldn’t really have art anymore—not contemporary art, anyway.

Maybe people are embarrassed to be “wrong” about art and clam up in face of technical language.

But nobody’s requiring a public to be involved in that part of the conversation. I’m sure I would find shop talk between doctors or computer programmers or any other serious discipline somewhat alienating. It’s just the nature of expertise, and why shouldn’t the discussion of art be complicated? If art does everything we want it to do, one would think that a lot of serious thought goes into it. The presence of that discourse doesn’t mean everyone has to think of art in those terms, it’s simply a specialized discourse. It makes sense that there would be a technical language shared by people who spend all their time working with art.

Anyway, I find this faux-populist critique of art and academic elitism really disingenuous because it’s usually trafficked by the most deeply connoisseurist classists and intellectually corrupt critics. It also diverts attention from the real, class-based issues at work. It doesn’t matter that artists and critics sometimes speak in specialized jargon when, in general, our access to aesthetics and the commons where ideas are exchanged via aesthetics is severely limited. Corporations and governments control these spheres of public discourse, and the public is left to work within the margins of these voices. So I think this “elitism” argument covers up much more troubling realities.

I guess we’re back to the question of what makes art valuable: its commercial worth or its intellectual reception?

Artists and art objects are valued in a multitude of ways. There’s the academic system, museum system, market system, critical system, all these different systems that have their own private heroes and villains, big successes and failures, that don’t necessarily correspond. Often people tend to reduce it to a market question.

I think the increasing dependence of art institutions on private money threatens to make contemporary art more isolated and insular, which doesn’t do anyone any good. Still, from a scholarly perspective, a work might be compelling and significant, but the public might find it obtuse. The real question is whether a museum is meant to instruct the public on how to find such things interesting, or is the assumption that art is self-evidently engaging for people?

What do you think?

I don’t know. In a sense, museums are trying to be both scholarly and populist at the same time. There’s not a clear answer for how the museum ought to function, it’s a transitional moment, between a paternalistic state model and a model premised on private stewardship. There seems to be a contradiction that lies at the core of the idea of the public arts institution – a problem that I think will force a redefinition of the museum, especially at a moment when museums are more dependent on private funding. Neither the populist nor the privatized models seem very attractive.

The deeper contradiction here cuts to the core of the museum’s public role. Do museums function primarily as paternalistic entities designed to educate and serve a public, or is their mission to provide a site for art discourse outside of market exchange, and provide havens for practices that couldn’t otherwise thrive in a commercial context?

Can museums really distance themselves from “market” discussions?

Well, the market is rarely discussed in a very specific way; that’s why people end up mythologizing it. It’s most often invoked as this ghostly force, this hand of god selecting some and banishing others. But, really, it’s just a bunch of people buying and selling things. Markets don’t have brains. They’re inconsistent, and they have no sense of their own history. Markets are a form of perpetual present. Even the term “market” is incredibly abstract, and we give it a false sense of concreteness by discussing it as though it’s a thing rather than a dispersed set of actions.

Are artists perpetually aware of markets?

I guess that’s why it’s nice being in LA. Conversations about the market aren’t necessarily happening here all the time – or at least they can be easily tuned out. An artist can get some distance from it here.

How does LA shape an artist?

In some ways, this city just makes it easier to be one. I was in New York before I got offered an adjunct teaching job at UCLA about ten years ago. In New York, I was writing for money, not really showing or anything like that. I was writing art criticism, then came to LA and stuck around. My entire art career really happened here. Professionally speaking, I’m a product of LA.

I think a place like New York suffers from an exaggerated sense of the market and its own importance. New York assumes that because the market is central there, it’s central everywhere. It’s really provincial in that way. It just assumes its provincial issues are of global import. The art world there is obsessed with the market, and I find that discussion overbearing. In LA, you can turn off the conversations you don’t want to be a part of. It’s harder to do that in New York, where there’s a strong emphasis on consensus. So I think having a distance from those kind of discussions has been really positive for me. I’m not saying one shouldn’t be aware – not at all – I just think one shouldn’t be overly conscious of the market. Friends of mine still working in New York have to try hard to tune out some of the chatter.

“on a practical level, LA’s a wonderful freedom from the drudgery of being useful”

Did you move here with the specific intention of tuning out chatter?

Actually, before I moved here, I thought LA was hell on earth: a spread-out car city. Not a very civic-minded place. That said, I’ve also found it to be a place where quality of life is higher, where one feels more autonomous. Things like that make it easier to be an artist in LA. The day-to-day isn’t demanding here, so you’re free to immerse yourself in the conversations you want. When you’re living in New York, your whole life becomes a string of negotiations with the city. LA lets you not think about certain things. On an ethical and civic level, I think there are some problems with that. But on a practical level, it’s a wonderful freedom from the drudgery of being useful.

This feature originally appeared in issue 17

BUY ISSUE 17