Queer utopia has become a cliché, and a pernicious one at that. People designate gay enclaves like Fire Island as utopian then proceed to reel off its shortcomings, when really the sites are homosocial heterotopias, places that mirror and upend the norms, places that uphold fantasy.

The upheld fantasy seems to be what lured photographer Matthew Leifheit to Fire Island, a famed gay gathering spot among the dunes of New York’s Long Island. Leifheit’s photographic series To Die Alive is a mad opera culminating in the area’s cruising woodland known as the Meat Rack. Men of different ages (Leifheit’s friends and lovers, or strangers cast on apps) tentatively anticipate debauchery. The men act out cruising, which itself is always playacting. Jeremy O Harris contributes two poems to the book, almost-spiritual, almost-satire. The second, built around the spectre of a “dark gay path”, ends with a crack about the sound of flip flops smacking on the boardwalk and sloshing through “the Judy Garland Memorial Path” as gay men enter the chase.

Leifheit conflates sex and death with camp flourish. He visits the sites where writers Margaret Fuller and Frank O’Hara met tragic ends. For the title, he’s employed one of my own favourite strategies: over-analysing lyrics from a gay bar banger, in this case a phrase from Ariana Grande’s Break Free, the sonic equivalent of a Red Bull. To Die Alive could be the next 007 film or garbled Hervé Guibert translation, an uncanny ridiculousness that reflects the way the artist scans across surfaces, seeking luminosity not hidden depth.

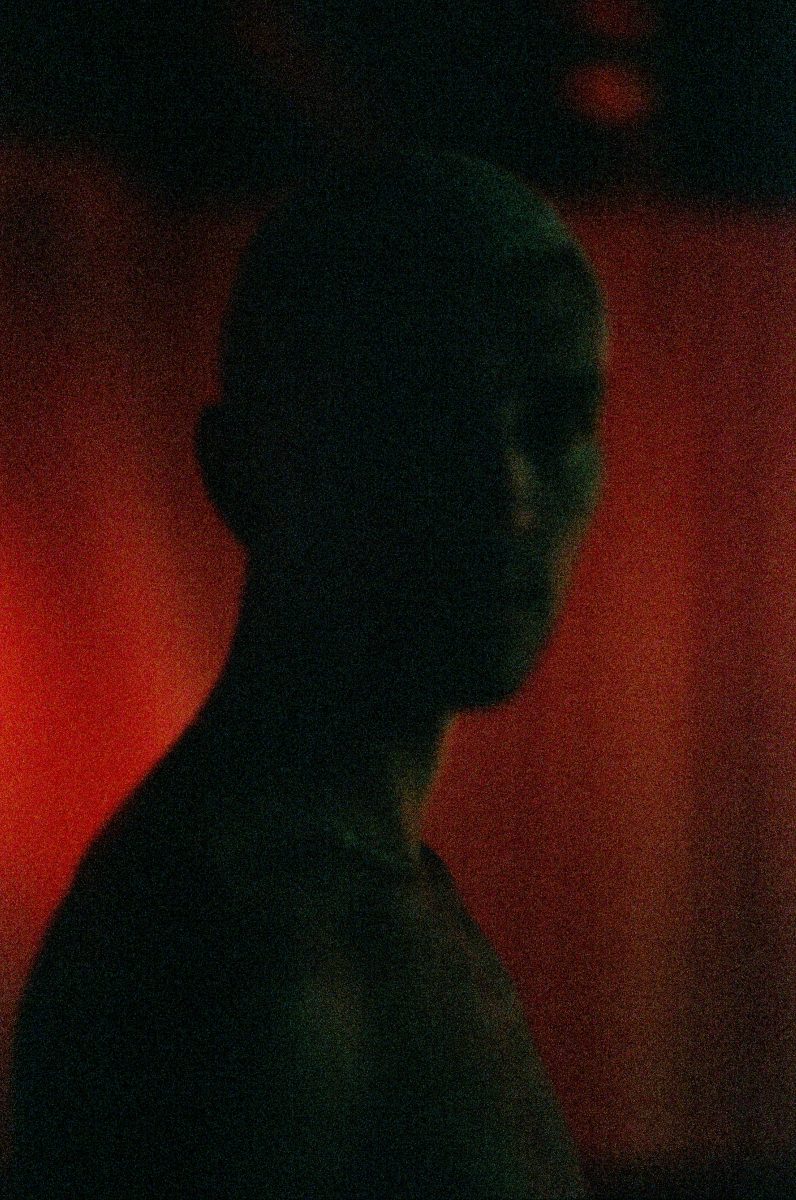

“The sky above is bright purple, yet almost-white and all-black. It’s an image of searching, not just for other bodies, but beauty, the sublime even”

Real nature is rendered nightclub-fake, a reverse-illusion. The cast gathers in stilted arrangements like nonsensical perfume ads. In the gaudy rooms and neoclassical terrace of the Belvedere, a ‘guest house for men,’ they appear like waxworks in the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland. Buildings are rendered in flames, as is a portrait of the Belvedere’s founder-architect John Eberhardt, made literally flamboyant. In an afterword, Jack Parlett, whose cultural history Fire Island is forthcoming, plays on the toponym, describing a site of “hedonism (burning the candle at both ends) and desire (being on fire for someone)… lamentation (a drag queen’s torch song) and relaxation (risking sunburn)”.

- © Matthew Leifheit

“To Die Alive is a mad opera culminating in the area’s cruising woodland known as the Meat Rack”

On a solitary sandbar, tire tracks conjure the dune buggy that plowed into and killed O’Hara in late July, 1966. The sky above is bright purple, yet almost-white and all-black. It’s an image of searching, not just for other bodies, but beauty, the sublime even. Leifheit provides an opposite to Kohei Yoshiyuki’s photographic exhibition Koen (The Park), (1979), in which couples in Tokyo bushes, and the voyeurs around them, are revealed by infrared bulbs. Leifheit seems uninterested in catching anybody out, in shaming.

The men may be mellow, stern, endearingly creepy. Their skin is variously suntanned, fuzzy, smoothed like sock-worn ankles, nubile, wrinkling, sagging, supple. Some look ecstatic, others wary, many ravenous. And what’s with the fish draping one pair? Curling from one gaping mouth is what appears to be the tail of another, as if swallowed whole while suffocating its host. I search online (cannibalistic fish + Atlantic), then stop and accept the tableau as myth: la petite mort, another enigmatically shimmering surface.

“The men may be mellow, stern, endearingly creepy. Some look ecstatic, others wary, many ravenous”

The participants, even in roleplay, debunk the notion of false intimacy. With their bare skin, proximity, vulnerability to contagion, even susceptibility to love, they are intimate, whether directed or not. Their contact builds atmosphere. They lie together, as in collude.

Jeremy Atherton Lin is an essayist based in the UK

To Die Alive by Matthew Leifheit is out now (Damiani)

This article originally appeared in Elephant #47 — Spring Summer 2022, available to buy here