While museums and art spaces remain closed in the UK into 2021, curators have been reflecting on the year that uprooted gallery-going for good. From March 2020, all venues were shut in response to the pandemic, with phased reopenings taking place from July. Museums across the world had to adapt before welcoming visitors back. At the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, the famous cylindrical ramps along the inner perimeter were installed with one-way markers to reduce aerosol transmission of the virus. London’s Tate Modern

, often celebrated for its open layout, became navigable only via certain prescribed routes. At South London Gallery, an installation where audiences could ride bicycles around a large space became subject to strict new rules.

Over the past twenty years, the spatial organisation of museums—and in particular, the effects on audience experience and perception—have featured heavily in art historical debates. Many centre on the self-conscious relationship between exhibition spaces and their function: some venues aim for invisibility via minimal, clean design (often termed the “white cube” approach), while others play a more active role in work’s presentation.

“Whether collections are organised thematically, chronologically, or by artist are significant curatorial interventions”

Whether collections are organised thematically, chronologically or by artist are also significant curatorial interventions, shaping art history for visitors and invariably reflecting the tastes and values of individual decision-makers. After MoMA’s major refurbishment in 2019, critic Roberta Smith

wrote that while the reorganisation led to a “more inclusive, less-definitive story”, the “Euro-American narrative is still too prominent”. Since 2019, the museum has reinstalled a third of its permanent collection galleries every six months as a potential model for freshening art historical narratives.

Structural changes in the wake of the pandemic have reignited these debates in earnest. One the one hand, modifications including warning signs and floor route markers draw additional attention to site architecture. On the other, removing touching surfaces and furniture reduces visitors’ awareness of spatial planning’s curatorial power—while limiting visitor numbers decongests the viewing experience. And in an era of decolonisation, there are worries that progress could be stalled by narrowed public exposure and dwindling access to gallery decision-makers. With pandemic measures set to remain over the coming months, what do they mean for the relationship between architecture, curation and meaning in Western museums and galleries?

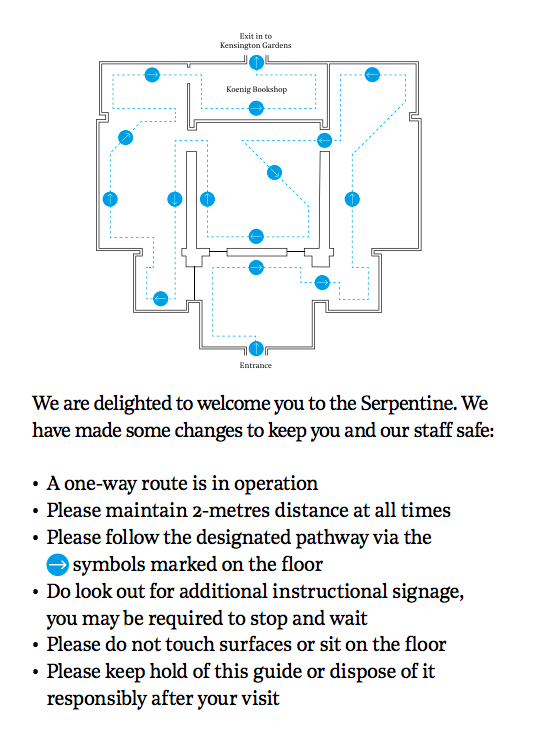

At the Serpentine Gallery in London, New York painter Jennifer Packer’s The Eye Is Not Satisfied with Seeing was being planned just as restrictions were announced. Curator Melissa Blanchflower was able to consider a socially distanced walkthrough route when first discussing the hanging with the artist, rather than scrambling to rearrange the layout. To ensure that visitors were not entering and exiting from the same door, a function room at the back of the building was converted into extra gallery space, and the venue’s bookshop was moved.

“Away from their galleries, curators are facing the most drastic upheaval of their creative careers—all in the name of public health”

“We decided early on that this show would be hung aesthetically rather than chronologically or thematically,” says Blanchflower, “which gives you infinite combinations of how to present the work.” This flexibility allowed the team to consider the multiple vantage points within the gallery, conscious that visitors would not be able to circle back or wander unguided through the rooms. The decision was taken to hang Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) (2020) so it was partially visible from the entrance. The mustard-hued canvas shows a reclining figure at home: they exude calm, but also the weariness of a summer spent campaigning for racial justice.

“I was really apprehensive about it not feeling like a conveyor belt that you’re forced to follow, like at an airport,” Blanchflower admits. “The open viewpoints really help to unlock that feeling.” Packer’s work combines domestic portraiture with depictions of plants and flowers at various scales, requiring variety in the optical planning. “There’s this need to be able to view some paintings from quite a distance but then also at a close proximity because of the detail,” she says. The route created a rhythm which allowed for this, subtly signalled with short, broken white arrows on the floor.

“Route prescription seems to go against all the impulses of pre-pandemic curation”

Gallery and museum-goers arguably now face a less spontaneous and incidental experience than before, with an increased didacticism introduced by curators. Critic Rosalind Krauss has described movement within the museum as “a constant decentring through the continual pull of something else, another exhibit, another relationship…the serendipitous discovery of the museum as a flea market.” Pontus Hultén, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art, Pompidou Centre, wanted to create a labyrinth through the works, resembling a city. By contrast, route prescription goes against all the impulses of pre-pandemic curation.

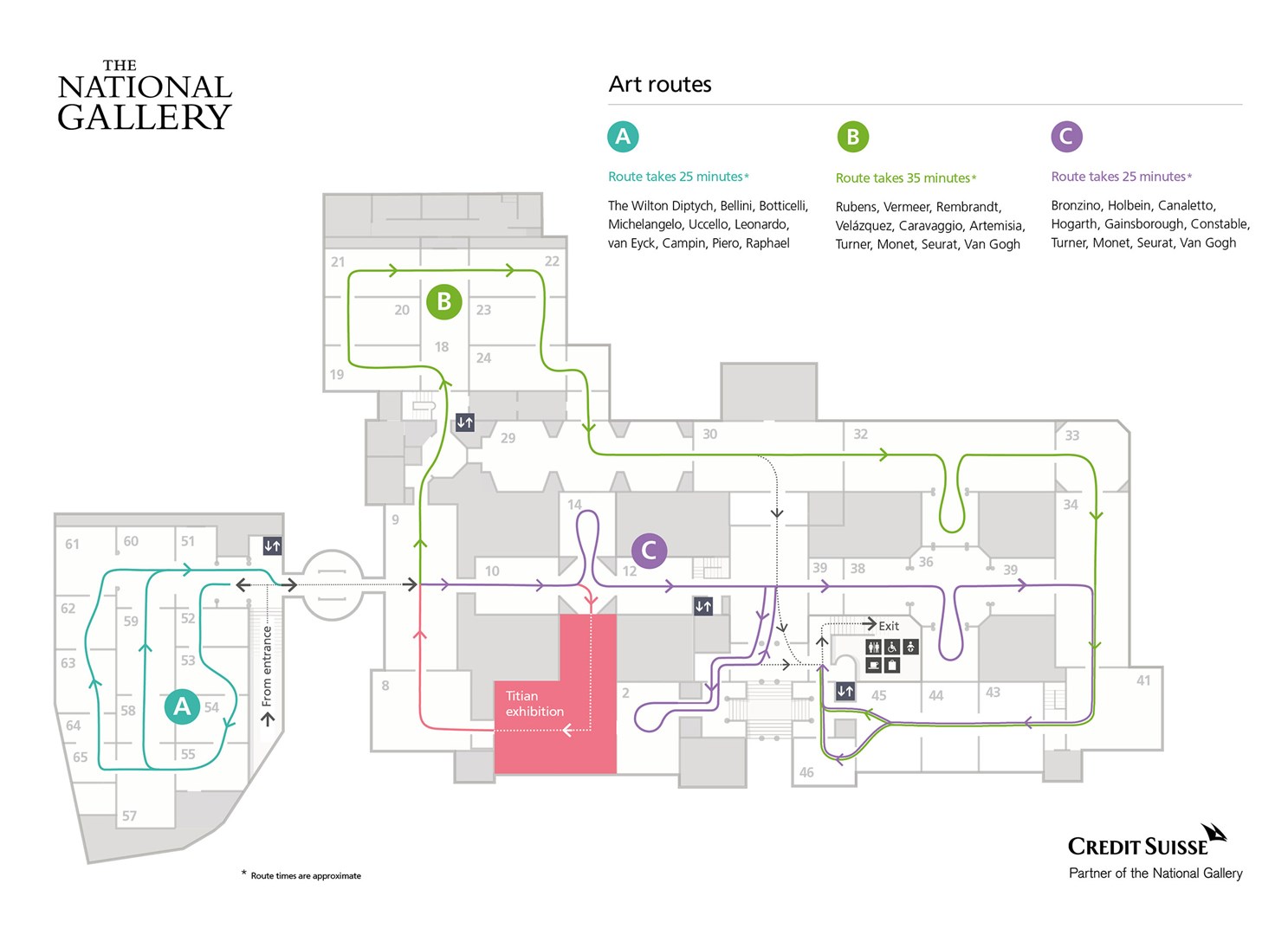

When London’s National Gallery reopened in July, it did so with three carefully planned routes through its vast permanent collection. Route A, the new map states, allows visitors to pass by The Wilton Diptych and works by Botticelli, Leonardo, van Dyck and Raphael. Route B circles past Rembrandt and Velázquez (the floorplan informs visitors it will last 35 minutes, resembling a park noticeboard instructing hikers). An inventory of works on each pathway appears on the gallery’s website (a daunting 397 on one route), complete with images, information, a download feature and links to print buying. But extensive planning does not always translate to a smooth visitor experience. After attending the National Gallery in July, the Guardian’s Adrian Searle wrote: “I thought of the supermarket, where I am now so aware of other people careening randomly about the place with their trollies, that I always leave without some vital item on my shopping list.”

Some art spaces are naturally suited to the restrictions mandated by social distancing. When museums closed their doors throughout March, the team at the Barbican Centre had just finished installing Toyin Ojih Odutola’s A Countervailing Theory in the Curve, a 90 by six metre semi-circular channel where artists are commissioned for site-specific projects. The work saw 40 new drawings installed from right to left, a life-sized cinematic storyboard depicting a fictional prehistoric civilisation run by female rulers and served by male labourers. By design, visitors enter at one end and trace the narrative through the space, guided forwards by Peter Adjaye’s immersive soundscape.

“The gallery can be seen to invite this idea of an unravelling storyline,” says Lotte Johnson, the venue’s associate curator. “Toyin saw the space as a metaphor in terms of thinking about how a narrative can unfurl incrementally.” There was an element of good fortune in having a project with such minimal and linear site design installed when the pandemic struck. Johnson recalls Bedwyr Williams’s The Gulch (2015) in the Curve, a “labyrinthine-style installation where you wandered through narrow passages and dioramas.” Such exhibitions wouldn’t have met the strict safety standards imposed for the mid-August reopening.

“Spaces like the Curve are naturally suited to the restrictions mandated by pandemic social distancing”

Museum directors also worry about access. Before the pandemic, the Curve was unticketed, a favourite of locals wandering through the Centre’s large lobbies and eateries. Last summer it required online pre-booking, and will likely do so again when allowed to reopen. Despite the ostensible positives of emptier galleries for viewers, the diversity of the visitorship may be suffering owing to digital, health and economic inequalities.

“As art historians and curators and art lovers, we’re really embracing the pluralities of art history—it’s not just one single canon anymore,” Serpentine Galleries’ Blanchflower says. “The need to make a single pathway through a collection—which can then be read as a single story of art—is something that really counters that.”

Johnson is still optimistic about working within pandemic strictures. “Even if there is a prescribed route, that route itself can ask questions and open dialogues between artists from different geographic locations and cultural histories,” she says. For now, works lie in wait. Away from their galleries, curators are facing the most dramatic upheaval of their creative careers—all in the name of public health. But their first impulse is to adapt, not remain attached to past conventions. It bodes well for museum visitors, who after months away will expect—and hopefully embrace—change in their favourite institutions. “You think you know a venue well,” reflects Blanchflower. “But to be able to interrogate the space in a different way is a great joy.”