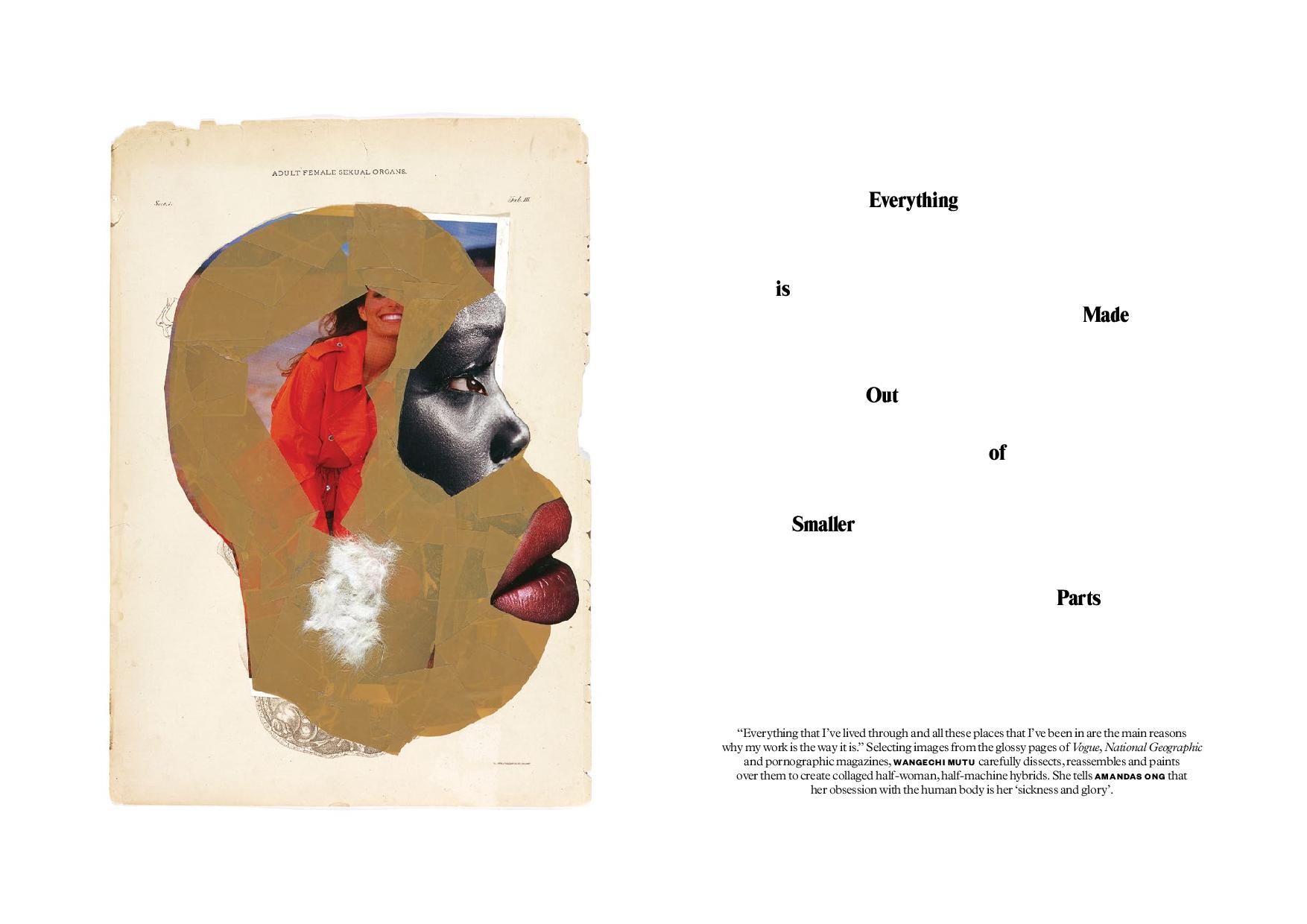

A potpourri of liminal spaces, Wangechi Mutu has lived, studied and worked in Nairobi, Wales and New York. Her lack of spatial and geographical fixity is reflected in her artistic practice, which resists easy pigeonholing—her work is not just about African culture, or the over-sexualization of women by the Western mainstream media. In fact, her preferred term for her women-creatures, ‘chimeras’, couldn’t be more apt. Tentacles, claws, guns and cyst-like growths protrude from her hybrid forms, transforming them into phantasmagoric beings that attract and repel at the same time. The indeterminate nature of these figures is somewhat reflective of her own life, which has been immersed in a hodgepodge of cultural settings.

“Everything that I’ve lived through and all these places that I’ve been in are the main reasons why my work is the way it is,” she muses. “Growing up in Nairobi, I wasn’t proud of my ambitions and I didn’t see art as what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. People around me said that art was merely a hobby, and that it couldn’t be taken seriously as a profession. It made me really sad to know that I had to leave my home to pursue the one thing that I was most passionate about.”

“Ironically, I found that New York was the most financially viable place for me to be. I was struck by the density of creativity in the city. That’s my story, really—it was necessary for me to leave home in order for me to understand what home means. My childhood and my mature mind will always exist side by side, in a state of fragmentation. I suppose that’s why I have a love of cutting things up because of these experiences, which have led me to believe that everything is made out of smaller parts. That’s my philosophy of life.”

She enrolled at Parsons, but left after a year for Cooper Union, where she studied art and anthropology. “I was extremely lucky to get into anthropology at a point when all the old-fashioned biases that had been built into ethnographic research were being debunked. Interestingly, my studies mirrored my own experience of living in New York as well, where I was regularly dealing with people’s lack of knowledge of contemporary African culture in general. They didn’t quite know who or what I was, and couldn’t place my accent anywhere. Some of the questions I got about my background were so astoundingly stereotypical: I suppose we categorize the things we fear.”

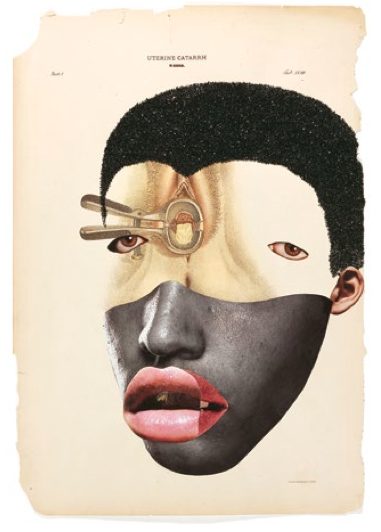

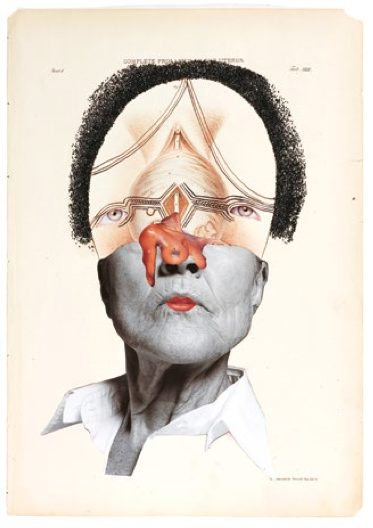

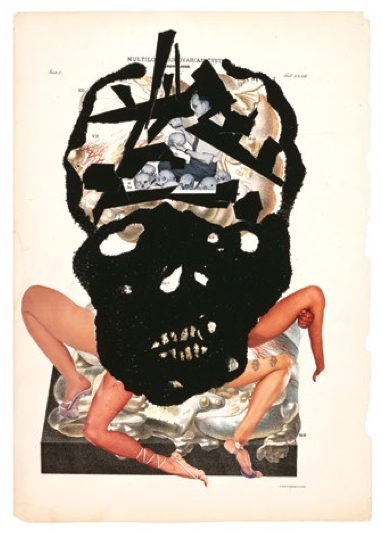

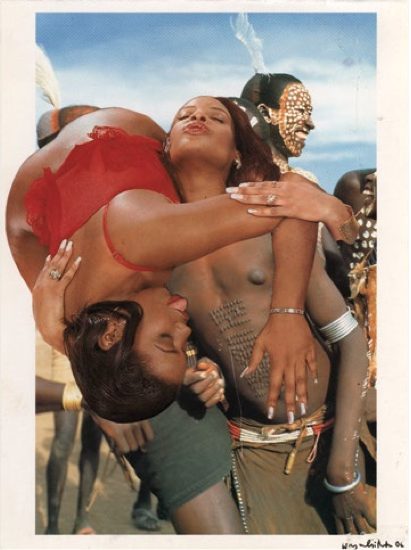

- Wangechi Mutu, Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumours, 2006, 1 of 12 works

- Wangechi Mutu, Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumours, 2006, 1 of 12 works

The ghoulish mutants that populate her work are a manifestation of these observations. They bring to mind Mary Douglas’s seminal work Purity and Danger, in which its author argues that classificatory systems emerge from our inclination to maintain the boundaries between the sacred and the profane. After completing her undergraduate education, Mutu was accepted into the prestigious MFA programme at Yale and chose to major in sculpture. “I wasn’t trained as a painter. Maybe that explains why my painted collages look so oddly textured and out of the box—it’s because I don’t know the rules.” Aside from making sculptures, she also experimented with performance, video and installation works that required viewers to concentrate intensely on their senses of smell and sound.

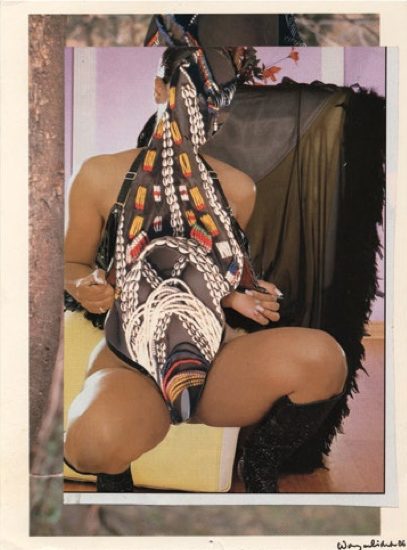

Graduating and moving back to New York led to a radical shift in her style. Her big, bold and eclectic pieces were replaced by smaller but more intimate works, the Pin-Ups, which were emotionally charged and aimed at thwarting ideas about the portrayal of women’s bodies. These mixed-media collages featured female amputees, and were inspired by the atrocities that had taken place during the decade-long civil war in Sierra Leone. The Pin-Ups heralded a new phase in Mutu’s career, and were some of her first works to focus on the complex intersections between African politics and sexuality. “I went from very delicate and quixotic drawings on paper to watercolour, and before I knew it I was cruising down this amazing journey towards large works again.”

Mutu is an aficionado of sci-fi films and readily rattles off a list of favourite titles. “It started with [David Lynch’s] Dune. I was so frightened when I first watched it, and then I couldn’t stop watching it. I also remember being completely enamoured with E.T.” She admits to a proclivity towards cinematic and literary works that fuse folklore with sci-fi, such as Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke. “Ultimately, my interest in mythology has to do with where I’m from. In Nairobi, there were many old male artists whose paintings revolved around traditional tales and folkloric narratives.” These stories inspired the titles of many of her works, including The Bride Who Married a Camel’s Head (2009) and Once upon a time she said, I’m not afraid and her enemies became afraid of her The End (2013). Intriguingly, these visual references constituted her first encounter with Western art. “They might’ve been “village fables” about magic, power and morality but they were rectangular pictures nevertheless, much like Old Master paintings hanging on a wall in a museum.” She has also recently completed a series of works for her upcoming exhibition at Victoria Miro that she describes as the culmination of her “newly unearthed interest in ocean mythologies”.

Parables about trickster creatures and humans morphing into animals were prevalent in her childhood in Kenya. She reflects somewhat wistfully, “When I was looking at these paintings all the time, I used to think to myself—that’s not the kind of artist I want to be. And then I left, and I felt this strange yearning to see these paintings again.” Sci-fi, she says, is making these legends and tales even more relevant than before, giving them a futuristic appeal that speaks to wider audiences.

For her, sci-fi is also the bridge between popular expectations of what is modern and what isn’t. “Like all other things that inform my work, good sci-fi is always about contrasting extremes. You’ve got dystopia, and then you have utopia. I was raised a city girl in an African city and I grew up watching the same shows as children in Europe and America, but my world looked completely different from what I saw on tv. When I go back to Nairobi today, I see traditional markets coexisting with shops where second-hand Western goods are sold, and there are gorgeous landscapes with the ugliest slums situated right next to them. These juxtapositions have actually given me a lot of comfort. I don’t have to justify the way my work marries the beautiful and the grotesque, because a lot of these mixtures are what my country is about.”

Fighting for Beauty

To describe Mutu’s images as violent is putting it mildly. The subject of conflict and turmoil is almost symbiotically related to her interest in the human anatomy. Her warrior princesses, who are rendered on paper, Mylar and vinyl, have undergone the trauma of being torn apart and then weaponized to become resilient machines. “Conflict is right next to our compassion and selflessness. We often think of it as being very distant from our lives, but that’s not true either. Birth is one of the most violent, difficult things you can go through. It feels like you’re about to die, but it’s also the beginning.”

Her own experiences of actual conflict were very remote: she was living in the suburbs of Kenya in 1982 when an unsuccessful coup took place, so the direct political aftermath didn’t affect her. It was 9/11 that altered the way she thought about war. “I distinctly remember fearing that the world was about to change, not because I’m a fatalist, but because America was finally noticing how it was being perceived from the outside. It’s a very hard thing for anyone to understand if they love their own country tremendously and haven’t left its shores. You won’t be able to imagine why somebody else might feel differently.”

When the terrorist attacks happened, she was going through a personal upheaval as she had just moved from a small town back to New York, and foreigners were being looked at with suspicion and paranoia. “And now we’re still reeling from the wars in Iraq and the Middle East. It’s brutal—we never stop and think how to make things better, but it’s always about annihilating someone else and his shadow.” To her, images of bullet wounds and carnage are a very patriarchal and dominant way of discussing war, and her work is positioned to provide a more reflexive perspective on things. During a residency in Texas in 2004, she made a video entitled Cutting, in which she played a farmer savagely hacking away at a pile of wood. This was also a symbolic representation of genocide. “I want to make works that are ambivalent. My own research on war made me believe that I am as capable of evil or hurt as anyone else, and that no specific person or type is a perpetrator. As for the male-oriented discourses on war, I don’t have any answers. I only know that the more powerful women there are in art and politics, the more diversity there can be in the way we communicate.”

If war is the most ruthless way of eradicating human contact and empathy, then Mutu wants to restore these elements through her highly tactile work. She uses Mylar as a base material for her flat works: it is a plastic sheet and a very robust insulator that is primarily used by engineers in their technical drawings. “It dawned on me how silly it was to continue working with paper when I could embrace the fluidity of Mylar. I am able to create this beautiful marbled texture on Mylar that I can’t on paper.”

“The best thing is that some of the effects that are produced are within my control, but others are completely unplanned and mysterious. I also use vinyl sometimes, to avoid getting “stuck” with Mylar. What’s most important for me, however, is to be able to be really close to the materials that I use. I believe that everything has a soul in the universe. When you cut something up you need to take responsibility for the power you have over it.”

As she takes stock of her career so far, she notes that there are battles that she feels she must fight. And fight she does—through her art. “From where I stand, I don’t think that normative ideals of beauty have changed immensely since I began working, but there certainly has been an encouraging shift.” She suggests that magazine covers today propagate less classism and racism than they did 20 years ago, citing the example of the July 2008 issue of Vogue Italia, which featured only black models, photographed by Steven Meisel. But she is also well aware that it is often difficult to ascertain if these are genuine changes, or merely trends that further exoticize racial differences. “Are magazines truly the place to fight for equality? Do we really want black Barbie? I mean, the doll has created so many issues for women, no matter what race they are, so it’s ironic that we still want it in our colour. Beyond all of that, we need to see that beauty is subjective but we don’t need to subject it to a hierarchy of value. The Europeans of the past would argue that classical music is intrinsically beautiful, but someone from a different cultural background might not agree. I’m an active part of that change, and my work speaks to all these issues without delivering static answers.”

All images (unless otherwise stated) courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.