1. Digital Romanticism

++JUST ONE THING – I’M NOT REALLY LOOKING FOR DATING AT THE MOMENT. WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE FRIENDS?++

J texted this to me one day. I shouldn’t be surprised considering what he first asked me when we started chatting on Tinder (++WHAT ARE YOU INTO? SEXUALLY, I MEAN++).

Just one thing – he was notifying something to me with the same tone I would use in a business call.

Just one thing, the meeting has been postponed by two days.

Just one thing, I forgot to water the bonsai.

To give a bit of context: after matching on Tinder, J. and I spent a few evenings together, had an intriguing email exchange, and went on a one-day trip to the seaside. All this lasted only two weeks. No drama, no pain. I can’t get that Just one thing out of my mind, though. Language is very important.

We all know how Tinder works. Swipe right: I fancy you. Swipe left: not my type. Very easy and simple. After the match comes the conversation. An interaction made of silent words, put together through the keyboard of a smartphone. No voice involved—just the click of fingers and thumbs on the screen. Typed sentences marked the beginning and the end of J’s and my “relationship”. The internet dating galaxy is dominated by language, after all. A multitude of misspelt words and noisy emojis typed by unknown users who might potentially turn into future boyfriends and girlfriends. A virtual land made of straightforward profile descriptions and rigorous information about its inhabitants’ looks (height, weight, body type), where semi-scripted conversations proliferate (A: Hey. B: Hey. A: Are u ok? B: I’m good thx. A: Horny?). In this apparently cold, hyper-functional world, is there any room for romance?

The online dating mania (by which I am affected) stems from a paradox: the actual body—the core of emotional and sexual attraction—is, at least at a first stage, only evoked by a bunch of readymade images arranged alongside outspoken measurements. “If the Internet annuls or brackets the body,” sociologist Eva Illouz wonders in Cold Intimacies, “how then can it shape, if at all, emotions?” To put it differently: “How does technology rearticulate corporality and emotions?” A few contemporary artists would seem to be asking themselves the same question. Alexandria-born Mahmoud Khaled is fascinated by the way the digital realm affects love and relationships, specifically in the gay community. In MKMAEL, a project that Khaled first presented at the Kunstverein Salzburg in 2007, the artist impersonates a partly fictional character called after the nickname he generally uses for his online chats on gay dating websites. Conceived as a series of ongoing episodes, the work gives an account of MKMAEL’s short- and long-term online relationships. For the exhibition in Salzburg, Khaled produced An Image Passionate, a book inspired by the Egyptian chick-lit series Abeer. Drama, deceit and cheap romanticism fuel the narrative. MKMAEL and AHMED AHMED meets online. An intimate virtual friendship sparks between the two, until MKMAEL reveals to his mate that his former profile picture—a Photoshop collage depicting a man holding a Pepsi and wearing a funny hat—doesn’t show his real self. Feeling hurt and deceived, AHMED AHMED decides to interrupt their virtual romance. A couple of months later he will contact MKMAEL again, asking for permission to use his contentious profile image. Structured as an online chat correspondence, the work reflects on the notions of identity and self-representation in a world (Cyberland) advocating anonymity. But that’s not all. More interestingly, Khaled unveils to his readers how effective the internet is, ironically, in building up romance. According to Illouz, the World Wide Web nurtures the idea that “the self is better revealed and more authentic when presented outside the constraints of bodily interactions”. When the body comes into play—when MKMAEL reveals the truth by showing the real picture of himself—things get messy. In terms of love affairs, the internet fills the space of Utopia.

Is there any chance of finding a own soulmate by surfing the net? If yes, can online love turn into a down-to-earth relationship? With the purpose of offering an alternative to the “shopping for humans” format of most dating apps, in 2014 Seattle-based artist Susie J. Lee created Sirens, a platform—in Lee’s words—“that should be compassionate to people who want to make meaningful connections”. No more swiping right or left: instead of setting static profiles, as on apps like Tinder (whose catalogue of human types has been compared to “morgues” by the artist), Siren opts for a more dynamic and evolving configuration. Men can see women’s answers to a new question each day before they ever see their faces (a function called “Question of the Day”). Attraction is encouraged through mental and emotional connection rather than selfies and pictures. Again, the body is temporarily set aside in order to trigger romance. “Our mission is to deliver something in which people can meet each other and connect in real life,” Lee says. The idealism implicit in online connections is here used to prepare the ground for real and successful relationships.

2. Desire and the Obscene

If Utopia shapes the mechanisms of online romance, the Obscene affects the dynamics of virtual sexual intercourses. The internet, in fact, is not exclusively a place to find meaningful romantic connections. It can be a torrid land, warmed up by lust and desire. The online dating world is able to offer a space for illicit pleasures; here the Obscene takes the form of the pornographic detail. According to Roland Barthes, “The image is peremptory, it always has the last word; no knowledge can contradict it, ‘arrange’ it, refine it.” In sex-oriented apps and websites like Grindr or ChatRoulette, nudity is the visual source for an extremely direct, explicit language. The virtual nature of the platform instigates an uninhibited exchange between users, saturated with the hyperrealism of X-rated selfies. Barthes’s “peremptory image” is now the “dick pic”.

“Intimacy can be channelled into different locations… 24 hours a day, wherever you are. Now you have access to these most private and intimate scenarios while on the street, in a café and so forth.”

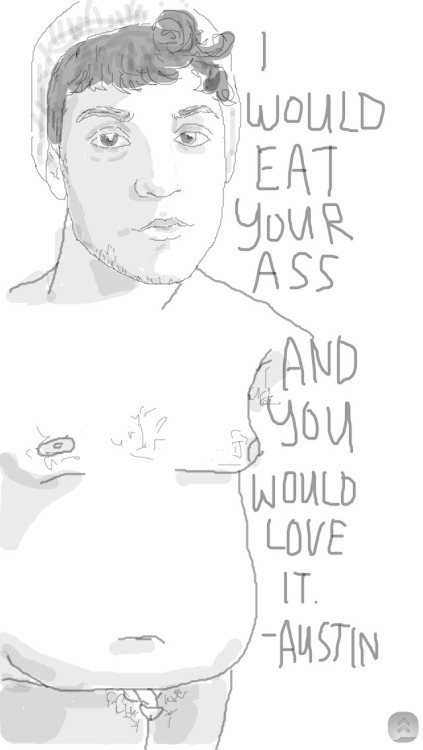

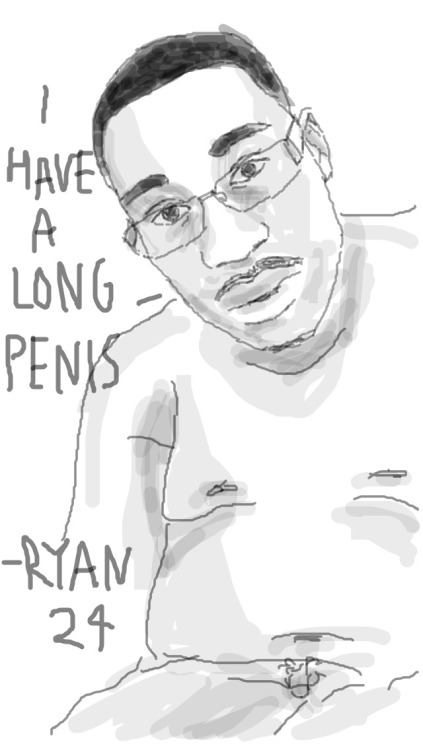

In a series of paintings started in 2014, British artist Celia Hempton has immortalized the licentious video material provided by the users of ChatRandom.com. The site connects people from all over the world via webcam, usually for the purposes of masturbation. Hempton paints the men on the screen in real time, representing the most intimate details of their bodies in an impressionistic style and a vibrant chromatic sensibility. The title of each painting reveals the date and the model’s name and home country (Jack, Scotland, 4th September 2015 or Michelle, Italy, 10th March 2015). The Obscene is here creative inspiration for a corporeal, sexualized atlas. Another female artist, Anna Gensler, has used her smartphone to draw caricatures of men she met on Tinder who sent her offensive texts. Gensler’s Instagram account, on which she posted the drawings, describes the project: “Objectifying men who objectify women in 3 easy steps: Man sends crude line via internet. Draw him naked. Send portrait to lucky man, enjoy results.” Charming opening lines and fragments from the virtual conversations are included in the artist’s unflattering portraits (a few examples: Ryan, 24: “I have a long penis”; Brian, 20: “You tryna get the pipe?”; Andrew, 19: “I bet your tight”).

Strong sexual desire permeates another work by Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow? (2013). The piece consists of thirty-two black-and-white photographs developed from screenshots of a conversation staged on the gay dating app Grindr. “Grindr allows gay men to connect with each other on the basis of their location. It is a very private sphere, as indeed is the iPhone: the messages inside Grindr are personal documents that require passcodes to be accessed. I wanted to use this undisclosed material to think about public issues,” Khaled explained in an interview that appeared in Ibraaz. Constructed out of imagination and the artist’s personal experience, the virtual exchange between the two men (they have no names) is set against the background of a tragic political event (maybe a coup or a military insurrection) taking place in an unknown town. The conversation alternates politics with sexual innuendo. Sex, in the end, wins: the guys arrange to meet up in a car. What interests Khaled most is the intertwining of public and private. In a geo-social app like Grindr, “intimacy can be channelled into different locations… 24 hours a day, wherever you are. Now you have access to these most private and intimate scenarios while on the street, in a café and so forth.”

Lust for sex, apparently, is not only a human desire. Even the pets that keep us company in our apartments have their own sexual needs. For a project conceived in 2016 during his residency at FACT, Liverpool, entitled Pet’s Pettings, Taiwanese artist Kuang-Yi Ku created a Grindr for dogs and cats. “The sexuality of pets is barely discussed in the field of science, and the animals’ sexual desire is even not yet recognized at all by science, thus almost completely ignored,” Ku explains. “When it comes to the ‘sex’ of pets,” he continues, “nowadays veterinarians suggest ‘spaying/neutering surgery’, for it prevents undesired pregnancy which might cause the problem of strays.” In order to allow pets to get sexual satisfaction, the artist, together with an engineer, an architect and a filmmaker, envisioned a scenario that includes new spray contraception technologies, apartments for cats in long-term relationships, love hotels and dogs sex parks, alongside the already mentioned dating app, where the animals can choose their sex buddies on the basis of their fur type and colour.

3. Romantic Assembly Lines, Fluid Personalities

Strong management skills are required to administer our online affections. We’ve all neglected someone from our list of Tinder “matches” or Grindr “favourites”. “Romantic relations… have themselves become commodities produced on an assembly line, to be consumed fast, efficiently, cheaply, and in great abundance,” Eva Illouz points out. “The result is that the vocabulary of emotions is now more exclusively dictated by the market.” Capitalism would seem to mould the way we find love online: setting up a convincing profile, scrolling down hundreds of potential dates, selecting the best option. Such a digital assembly plant allows us to expand our reach and, simultaneously, economize time. In 2014 Australian artist Tully Arnot created a sculpture consisting of a silicon mechanical finger tapping “Yes” in response to each and every Tinder profile appearing on the screen of a mobile phone. As Sarah Cascone highlighted, “Lonely Sculpture is a reflection of both our desire for human contact, and of the isolating nature of social media networks and online dating.” The longing for brand-new matches—epitomized by Arnot’s artificial finger—makes us act like workers in a production line. Not always a winning strategy, since it can lead to feelings of loneliness and alienation.

Even though it doesn’t sound much fun, setting up a Tinder profile can involve creative imagination of a sort. If global marketing rules force us to sell the best version of ourselves to possible customers/lovers, any time we set up a new account we create a new internet-based public persona. When the internet is on, our extended online personality gets porous and multifaceted; the more profiles we manage, the more roles we accept to play. That’s what digital identity is: a collection of elaborate, well-thought-out virtual performances. In 2014 artist Brian Lobel, supported by Brighton-based LGBT producer Pink Fringe, conceived an “art-cruising” Grindr. Performr let users watch live art performances in the palm of their hand. Emulating dating apps’ structure and functions (geocaching, text/photo chat, “block” option), the platform reflects on the link between identity and online performativity. In the pilot phase of the project (which is still in the process of development), a few artists were commissioned to create performative works for the app. One of them, London-based Scottee, presented an online “Guess Who?” performance: after asking an unknown user his name and location, the artist launched himself into an in-depth Google search about that user, sending back the found information in the form of a questionnaire. The aim of the performance, according to Scottee, was to figure out “how much we reveal about ourselves online”. Or, to put it another way, how many different selves the internet allows us to be.

“Disappointment is part of the game, though. If I swipe right, I can’t help but take the risk.”

4. The End of the Illusion

As our own online selves are getting more and more fluid, so are our most intimate desires. On Tinder, Grindr or any other dating app, we might look for sex, love or friendship all at the same time. We can promise eternal devotion to A, immediately after sending a “dick pic” to B. Our digitally shaped, adaptable egos make us crave “this”, as well as its exact opposite, “that”. Wherever there’s wifi, our identity turns to liquid.

But let’s go back to J. As you might have supposed, we’ve never become friends. The 5,750 characters that we exchanged in our online conversations are now archived in the memory of my iPhone—alongside dozens of other turned-off potential romantic connections. In the sci-fi movie Her (2013), director Spike Jonze offers the weirdest future scenario: a romance with your own computer. In a futuristic Los Angeles, Theodore falls in love with Samantha, a super-intelligent Operating System whose functions include virtual personal assistance and a dating service. The two embark on a romantic online-based relationship which, sadly, will soon come to an end: Theodore will find out that he’s not the only one for Samantha, who is simultaneously dating hundreds of other humans. As dating-app users, we all know how bitter the pill can be. The speed of online romantic production can cause information overload. Disappointment is part of the game, though. If I swipe right, I can’t help but take the risk. What’s behind any phone screen, after all, is the most complex and inextricable of all minds: that of another human being, longing for one more connection.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 30

This feature originally appeared in Issue 30