In January 2014, Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan couldn’t appear in person at a political rally in the city in Izmir, but he still made his presence felt for the masses: flickering into view as a giant hologram instead. Such razzle-dazzle trickery might recall the rap superstar Tupac’s posthumous holographic gig at Coachella in 2012, but Erdogan isn’t the only statesman to embrace techy showmanship; India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi also made campaign trail appearances around his country as a “live” 3D avatar.

We Are the People. Who Are You?, the latest group show at central London’s Edel Assanti gallery, takes its title from a 2014 Erdogan quote—a riposte to critics of his heavily authoritarian policies, in the year that he became Turkey’s President, and two years before he crushed an apparent coup d’etat. This is a sleek, streamlined collection that suits its compact setting—yet it manages to evoke themes that are personal and global, historical and devastatingly pertinent: the scrappy unravelling of democracy, mass power and mob mentality.

- Farley Aguilar, Bat Boy, 2018

- Karl Haendel, Hillary, 2016

The show’s opening piece, Anna Jermolaewa’s film Political Extras (2015) documents a “mass demonstration” the artist arranged at the Moscow Biennale, entirely populated by paid extras from a Russian web forum which advertises odd jobs from “modelling” to political events. We watch the “protestors” (mostly of retirement age) dutifully bearing placard slogans such as “Down with Contemporary Art” before collecting their nominal fee of 500 roubles (just over £5 as I write this). The spectacle seems sweetly absurd, before more uncomfortable thoughts dig in: how much value lies in a vote or demo; what social/generational perspectives might this particular group of Russians (born long before late-eighties “Glasnost”) have—or is this particular “cause” just too silly to count?

There’s no time to feel supercilious here—not while rent-a-demos also exist in “metropolitan elite” London (take the 2018 story of a UK casting agency and an anti-Qatar protest), and our own fractured nation is raging over a “people’s vote”. Instead, we could find solace and sorrow in the beautifully gritty sketches of Victoria Lomasko, whose Other Russias (2017) graphic novel depicts “hidden” humanity, from young offenders to LGBTQ+ activists and youth in rural communities. And we might consider how swiftly, imperceptibly, world history is forged. Nikita Kadan’s 2018 sculpture Tiger’s Leap is based on early twentieth-century farmhand tools turned revolutionary weapons, and also nods to the 2014 separatism/turmoil in the Ukrainian city of Gorlovka. At the far end of the room, Karl Haendal’s ultra-realist larger-than life pencil portrait of Hilary Clinton looms, while an infant’s voice recites the first names of US Presidents; the work’s symbolism has rapidly shape-shifted since its 2016 creation—just now, it feels grandiose, futile and ghostly, all at once.

“Throughout We Are the People… there are hints at how media reportage affects mass consciousness”

Of course, art has historically critiqued democracy—the satirical sting of Hogarth’s 1755 series The Humours of an Election certainly still smarts. And we might display a modern fixation with calling out “fake news”—and Twitter feeds are littered with “didn’t happen” GIFs—but that issue of authenticity is age-old, too. Throughout We Are the People… there are hints at how media reportage affects mass consciousness: in Farley Aguilar’s 2018 oil painting Bat Boy, where a lone figure chills over tabloid schlock in The Weekly World News; in Jamal Cyrus’s Kennedy King Kennedy (2015), where seismic headlines from African-American publication The Chicago Defender

are laser-cut onto papyrus sheets. Particular stand-outs come in Emmanuel van der Auwera’s smart deconstructions of everyday mass media: in White Noise (2018) shapes emerge from an apparently blank static screen; these turn out to be the footage of US airstrikes in Baghdad, leaked by whistleblower/heroine/activist Chelsea Manning—for me, personally, watching my birthplace (where many of my family still live) being decimated for “democracy” is a recurring nightmare vision. In Red IV (2018), Van der Auwera uses an offset panel from a newspaper printing press, to hone in on a shot of Hilary Clinton’s supporters learning of Trump’s Presidential victory; we see incredulity, horror, possibly hilarity. Stuff happens, right? Yes, that really happened.

Back in 1945, British art don Kenneth Clark wrote the essay Art and Democracy, in which he opined that market research and other means of measuring mass desires were “instructions in the destruction of civilization as potent as the flying bomb and the tank”. In 1964, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “the medium is the message”. And in the present day, we’re also acutely conscious of how much “mass opinion” impacts on media reportage. As a journalist, in my last full-time role at a British national newspaper, my editor advised me to pay heed to the “most-clicked” stories on the website; when I checked, the only music-related “hits” were creepy upskirting shots of female pop stars. As a consumer, I wade through clickbait, trolling and epic, ephemeral hot takes on everything. It is an age where the candy-coated mindfuck of Rachel Maclean’s art feels incredibly well placed—and her 2016 video It’s What’s Inside that Counts is a distinctive blast here, from data-fuelled masses to disfigured emojis and snappy techno tunes.

- Victoria Lomasko, Other Russias, 2017

- Emmanuel van Der Auwera, White Noise, 2018

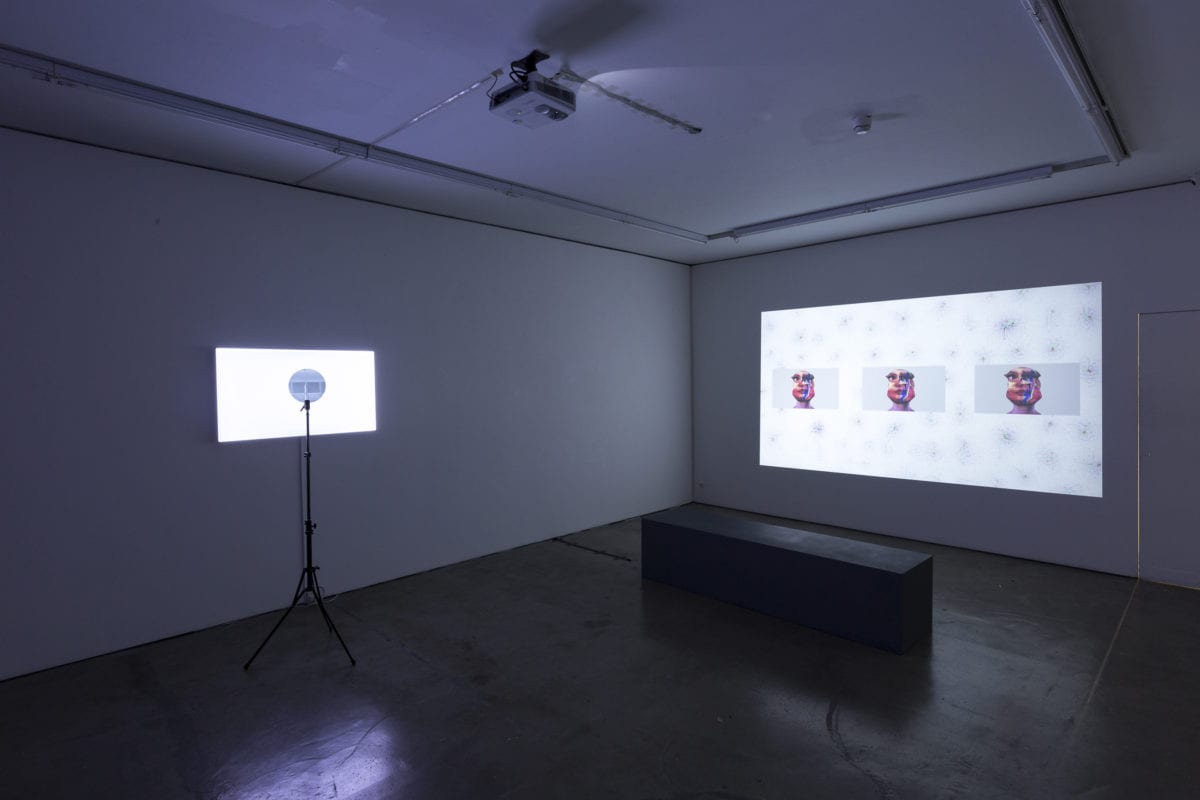

How much do we allow the “majority” voice to dominate? In Zach Blas

and Jemima Wyman’s multi-screen installation I’m Here to Learn So (2017), infamous short-lived Microsoft chatbot Tay is reanimated: an AI profile modelled on a teenage girl—who within hours exposed to online debate, had mutated into a misogynistic, homophobic, white supremacist monster. The sensation is a funny, terrifying hot mess—echoed a few feet away by Funda Gül Özcan’s psychedelic installation It Happened As Expected (2018): modelled on a dive bar, and featuring a hologram of the artist morphed into an apparently contrite President Erdogan. In We Are The People… there is no safety in numbers.