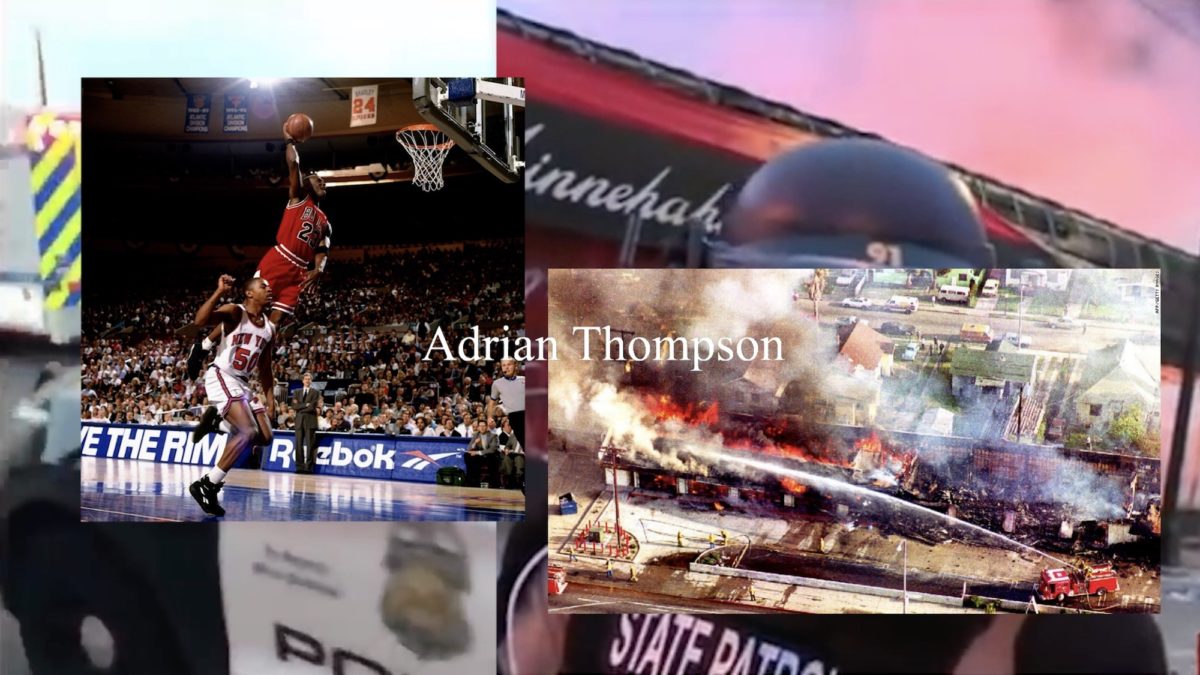

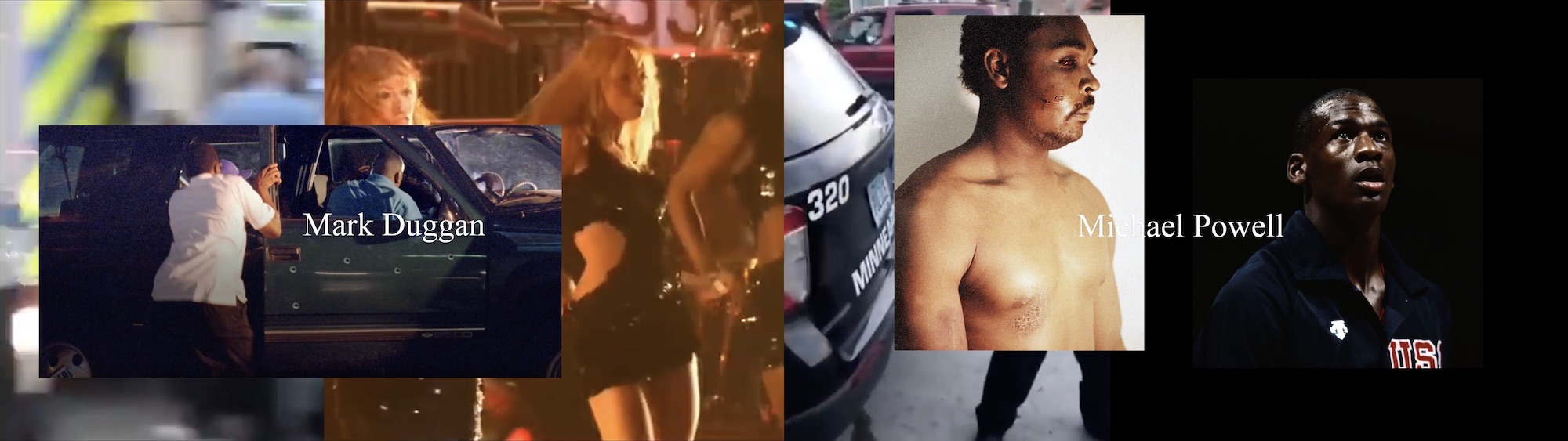

In Anglo-American culture, music of the Black diaspora has been the dominant sound of the past century, and since the turn of the millennia, its alignment with visual performance has come to dominate what we see as much as what we hear. As such, AmericanGods_250520, a video artwork that I created to process the contemporary Black narrative of brutal struggle alongside its counterpoint of celebratory resistance, juxtaposes the murder of George Floyd with a seminal performance by Beyoncé. Both images are underscored by the beautiful and tragic composition of I Am a God, by Kanye West.

The talent displayed by both Beyoncé and Kanye is the culmination of an incubated culture that was necessitated by slavery and honed in the Americas during slavery’s legacy. In the moment of forced removal from their homeland, indigenous Africans were viciously separated from their possessions and, in turn, lost their connection to millennia of material culture and the knowledge contained in the physical objects of their heritage. In the hell of the plantations, the only permissible expression of tradition was to be found via mediums inextricably linked to their bodies—their bodies essential to carrying out the work of their masters. Toil and sorrow became their existence. Dance and song, in turn, became their resistance.

By depicting the turbulent, gestural and sonic bodily convulsions of Beyoncé and Kanye respectively, AmericanGods_250520 conveys the turbulence attached to Black narratives such as George’s—who went from living to dead in an instant. In a single moment, the video artwork tells multiple, conflicting stories of rapture, agony, wonder, revelry and effort. The disorientating and uneasy four-minutes of viewing is a taste of the daily discomfort Black people experience in a white world. This lived experience is not exclusive to Americans, the recent protests having struck a chord in the UK and beyond because of the common, disquieting knowledge that one’s minority status, far too often, results in mortal tragedy. This truth is foregrounded in AmericanGods_2505020 by the roll call of UK deaths as a result of police abuse of power.

“The disorientating and uneasy four-minutes of viewing is a taste of the daily discomfort Black people experience in a white world”

For me, as a Black man who has been subjected to such abuse, it was important to memorialise the murder of George Floyd in some way, and for me as a Black architect—concerned with the relationship between people and constructed things—it was important to do so in a manner befitting of Black culture. The result is a digital film, the same medium used to capture the Minnesotan murder and broadcast it across the world.

In its aesthetic, AmericanGods_250520 owes debt to the work of Arthur Jafa, whose films are the litmus test for any meaningful contribution to Black cinema. Over his career Jafa has been preoccupied with how to make “Black cinema with the power, beauty and alienation of Black music”. Immaterial constructions such as film and music provide the spiritual foundation upon which more material constructions are built. For example, the murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement has led towards the destruction and reconstruction of society’s monuments.

This translation from immaterial to material is where, for me, AmericansGods_250520 has led to; a quest for a material culture that honestly reflects the resilient beauty of contemporary Western Black origins; a quest for a material homecoming of sorts as a conscious step in responding to an extension of Jafa’s question, with regards to my own discipline; how to make Black architecture with the power, beauty and alienation of Black cinema?

For Black people, the barriers to exploring and identifying such a material expression remain. The pursuit requires both capital wealth and social privilege, neither of which are generally found within the Black community. However, there are a number of artists who hold clues as to what an equivalent material expression of AmericanGods_250520 might look and feel like.

In a quintessentially American depiction (considering the nation’s endemic levels of police violence against Black men), the artist Sanford Biggers, in his series BAM, depicts small, brown, foreign figures standing resolute against a hail of bullets which chip away at their strength. Captured on film, the mutilation is both a modern and mesmeric depiction of mechanised terror: the gun. The artwork’s medium of violence is exactly that which confronted Africans in their villages at home and plagued them in plantations abroad. In the film we see the figures reduced, their bodies dismembered, their strength compromised and their presence diminished. But in a nod to the American dream, those that survive this onslaught are cast in new light. Biggers chooses to cast them in bronze—a transformative moment in which the descendants of tremendous viciousness are heroically reborn.

“Immaterial constructions such as film and music provide the spiritual foundation upon which more material constructions are built”

In AmericanGods_250520, this tale of resurrection is told immaterially by the portrayal of martyrs such as Eric Garner and George Floyd, alongside idols such as Michael Jordan and Jay-Z, pointing towards the resilient capacity of the Black community to turn collective trauma into new revival. In BAM, Biggers materially depicts rebirth and trauma by casting his figures in a medium loaded with cultural significance. He at once situates his work at the centre of Black canonical art while commenting on the enduring heartache of African pillage, the final artworks making reference to the Benin Bronzes and in turn their theft and retention by a colonial super-power—Britain.

The proliferation of Britain’s empirical horrors across the world, including the desecration of Africa from the sixteenth century onwards, was enabled by the advancement of domestic seafaring technology. British ships involved in the transatlantic slave trade sailed from Britain to Africa with a cargo of manufactured goods, then from Africa to the Americas with a consignment of abducted people, and onwards from the Americas to Britain laden with the raw material those abducted people were forced to produce: tobacco, cotton and sugar. The second part of this journey, the Middle Passage, was a particularly brutal and deadly phase of the slave trade, with conservative estimates suggesting 1.8 million enslaved Africans died crossing the Atlantic.

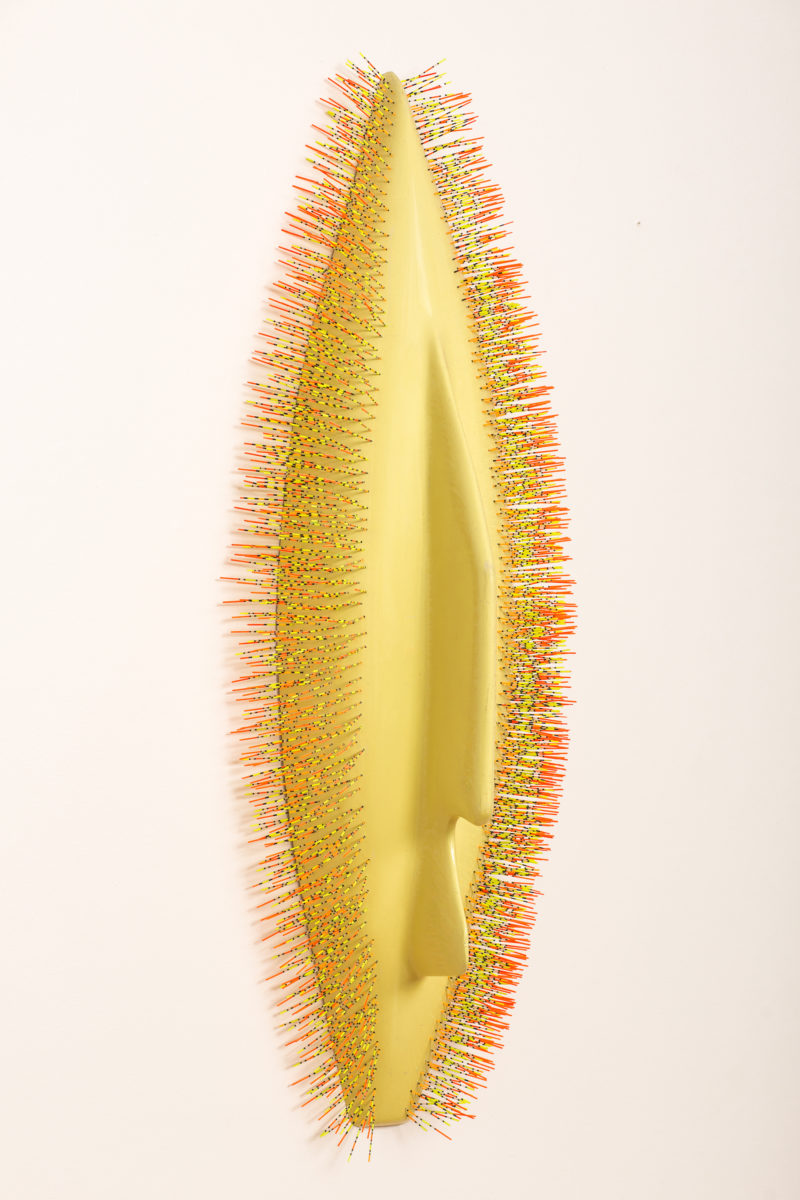

- LR Vandy, Yellow Waggler, 2015

- Crimson and Black, 2019. Photo: Dee Haughney

- Pomp & Circumstance, 2019. Photo: Matthew Booth. All courtesy the Artist and October Gallery

The story of the Middle Passage is the story of British globalisation. The story of British Black resistance is the story of surviving this horrendous nightmare. It’s a story the UK artist LR Vandy retells through the reimagining of the vessels that carried such trauma. In her series Hull, Vandy appropriates boat-like forms to construct mask-like objects. Formally, the sculptures are reminiscent of the traditional masks of indigenous African cultures, where masks have a spiritual and religious meaning. Poetically, they speak of a culture lost at sea, a memory of home distorted. These masks, instead of marking the progression of seasons (as might have been the case historically) commemorate the transition from liberty to captivity.

In the construction of such masks Vandy recognises the trauma of the Middle Passage by concealing it, much like the metaphorical masks Black people use to conceal the anguish of their historical and everyday experience. In the vivid colour and slick finish of her work Vandy injects hope into this narrative of ordeal. Much like the work of Sanford Biggers, and what I aim to convey with AmericanGods_250520, she tells a story of celebratory endurance and pain. In an instant, Vandy commandeers the vessel of her origins to confront malevolent terror.

“We must challenge the constructed objects that dominate our space physically and visually”

The resonant tone of Black resistance is predominantly fleeting and temporal, but both Sanford Biggers and LR Vandy convey an enduring material equivalent which honestly depicts the story of Black diaspora within the contemporary Western world. Through their work, they translate the concurrent sentiments of “power, beauty and alienation”, as contained within AmericanGods_250520, into the material occupation of space. This is important because although immaterial constructions have real world consequences, they only go so far in speaking to power. To address power, and redress the imbalance of social equity in a holistic and meaningful way, we must challenge its material constructions as much as its immaterial foundations. We must challenge the constructed objects that dominate our space physically and visually. To do so we should unpack the energy embodied in our American Gods and channel it into the formation of Black sculpture, Black Buildings and Black institutions.