Oreet Ashery’s work has long dealt with tricksy issues relating to gender, political fictions, the nature of communities and more. Through her performative, installation-based video works and other pieces, Ashery’s unique work has spanned everything from the large-scale sonic performance Passing Through Metal, which involved mic-ed up knitting needles and a death metal band; to 2014’s Tate Turbine Hall piece The World Is Flooding, created alongside asylum seekers to re-enact Mayakovsky’s play Mystery-Bouffe using banners, costumes and headgear made from cleaning materials and a zine; to a performance, concert and album-release Artangel commission Party for Freedom which looked at the rhetoric of “freedom” across the political spectrum; to a 2003 piece in which she dressed as an orthodox Jewish man and went to join the yearly dance celebration Lag Ba’Omer at Meron Mountain in the north of Israel.

“Even just talking about illness, death and dying seems to be a misbehaviour…”

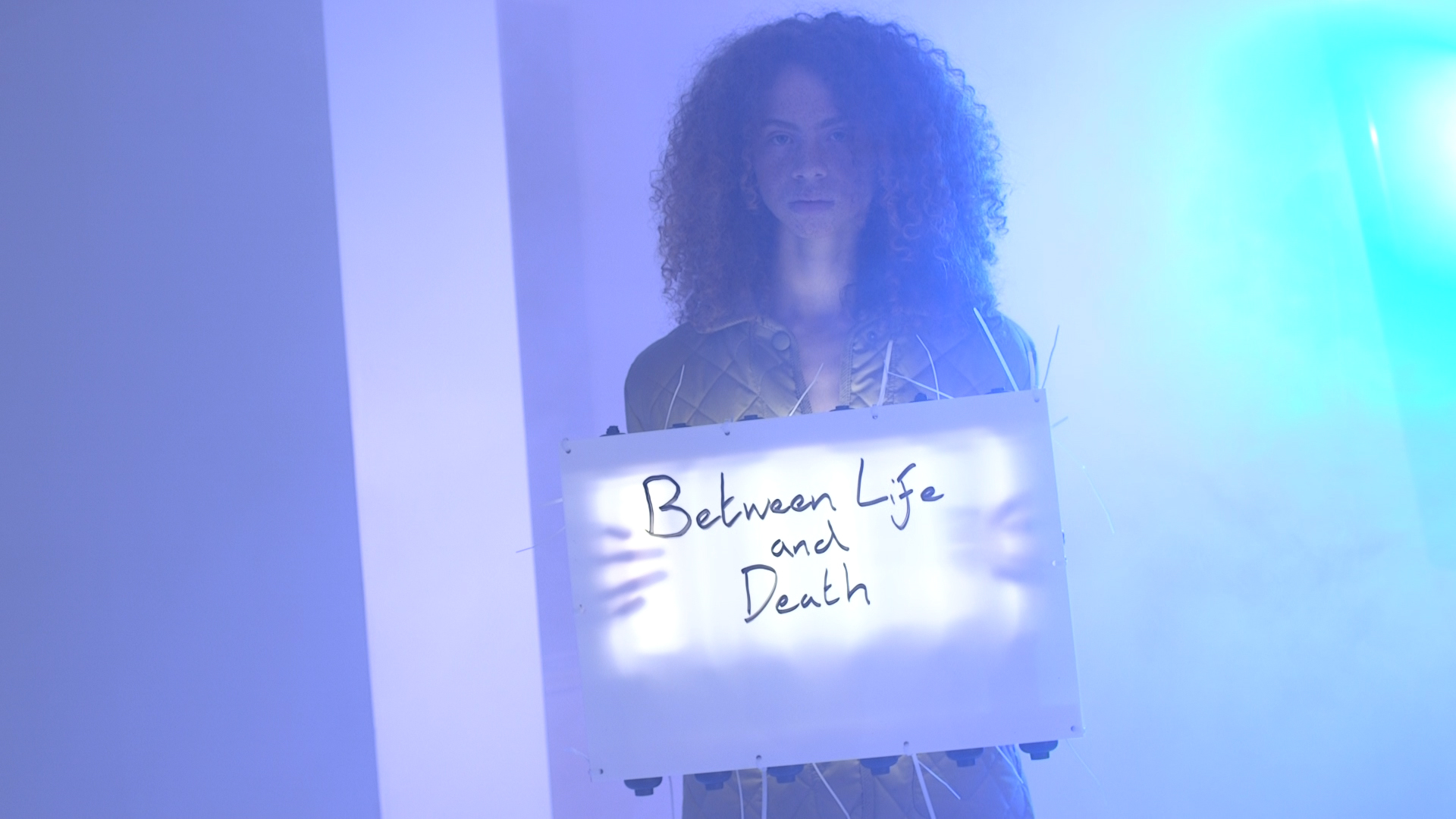

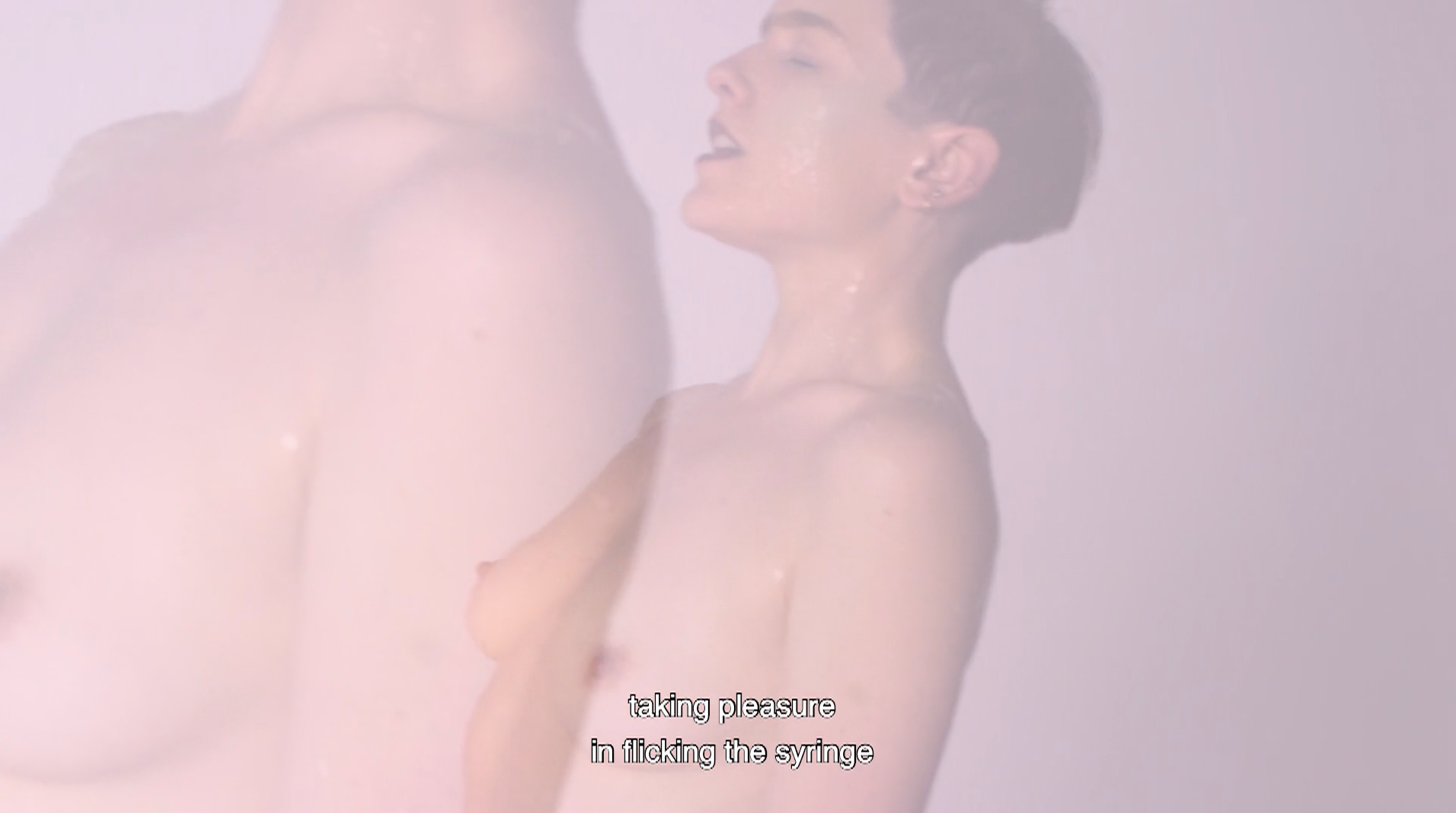

Perhaps her trickiest subject to many, however, is death. In 2016, Ashery created Revisiting Genesis, a video web-series in twelve episodes and a feature length experimental film which mixes fictional dialogues and real-life interviews with people who have life-limiting conditions. The work explores ideas around palliative care, feminist reincarnations of women artists, the potential digital technologies of dying and more. The series is currently on show at Wellcome Collection alongside works by late photographer Jo Spence in the exhibition Misbehaving Bodies. I spoke with Ashery about exhibiting with an artist who’s no longer alive, her thoughts around death and the role of humour and absurdity in her work.

What are your thoughts on the show title, Misbehaving Bodies? Surely death is what all bodies do eventually, so it’s not really “misbehaving”. To me, a body “misbehaving” would be one that lived forever.

To stay alive forever could be boring! It’s near impossible to speculate on that: our whole essence as conscious and living beings is defined by the knowledge of death. I guess one of my interests in the politics of death and dying is that it is a heightened version of life. So if you are poor and your life is precarious, it will be more so in the process of dying—and I have witnessed that. For example, if you are a racial, gender or body-able minority, there’s a good chance that your death will be defined by that. Or, if you have loving and available friends, then dying is likely to be easier. In this sense Misbehaving Bodies relates to how we die. There are certain expectations around dying that I hope the exhibition works to defy. Even just talking about illness, death and dying seems to be a misbehaviour… My social media popularity plummeted since I became interested in the subject! (I’m only joking… but you get my drift.) There is a real need for those sort of discussions, judging by the numbers of visitors to the show and the eruption of discourses in the art world around care and health.

- Oreet Ashery, Revisiting Genesis, in installation shot of Misbehaving Bodies. Courtesy Wellcome Collection.

What was the experience like of being in a joint show with Jo Spence, an artist who’s no longer alive? Can you tell us a little more about how you approached presenting your work for the show?

It was already a little uncanny: when I loosely looked at my diaries—I have about twenty-five of those—for an image I wanted to use, I completely randomly came across an entry related to Jo Spence that I wrote as a young BA art student. When I read the entry it was so interesting to realize how important my observation was to the formation of my practice around politics of identity. Then the show with Spence made even more sense. Revisiting Genesis is all about the artistic legacy of women artists, and so it was extremely interesting to witness it first hand and be part of that responsibility, being trusted to work with someone’s else’s legacy.

Other than that, it was a bit lonely at times being the only living artist. I got a great deal of support in the process from George Vasey the curator and Bryony Harris the project manager, but you still want the second artist with you to reflect on the process. I am still curious as to what she would make of the show. I might find out one day…

“It was a bit lonely at times being the only living artist”

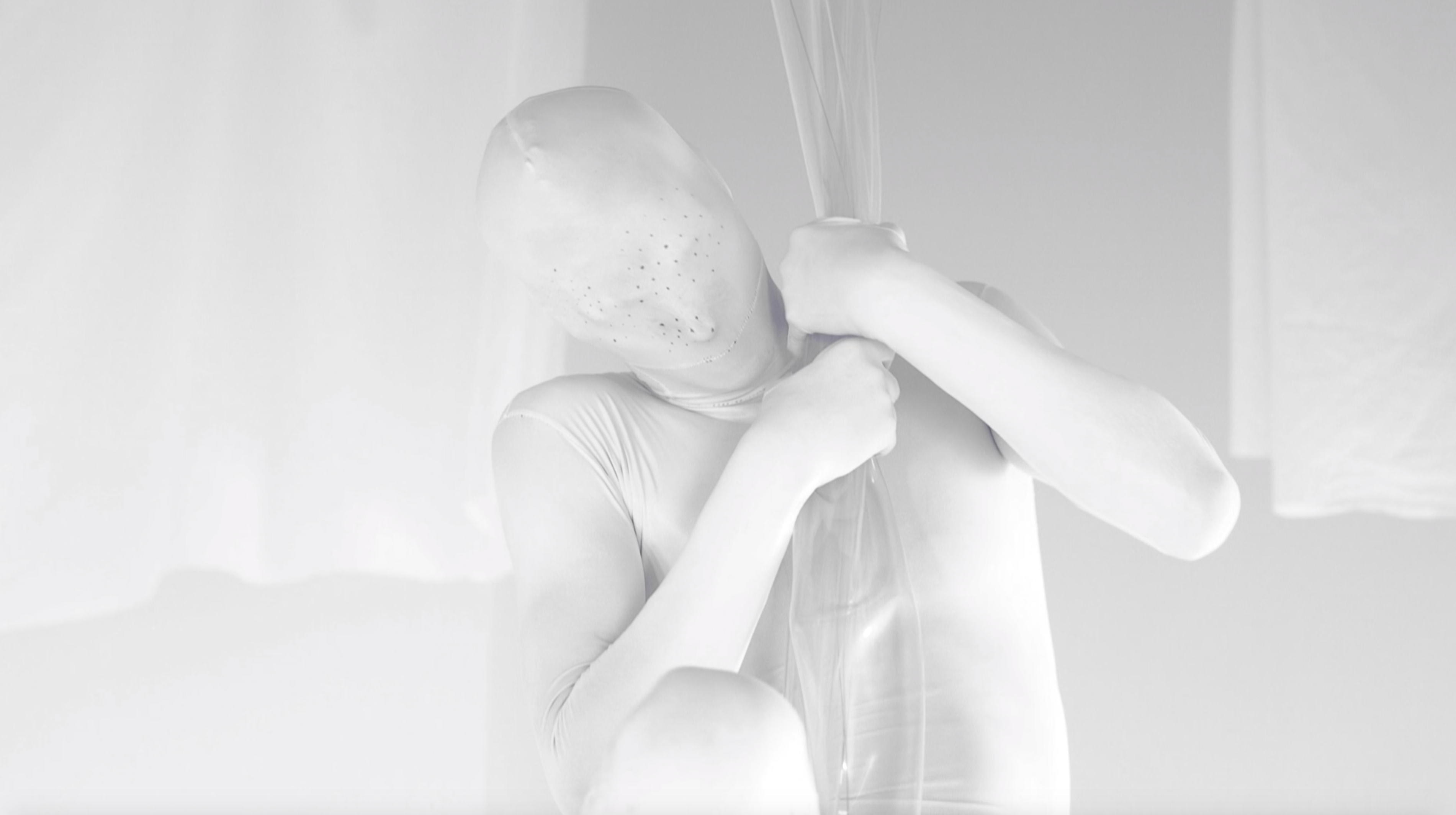

In presenting my work, it had to be configured as a conversation with Spence’s work, so the idea of showing the work on one screen as I did in previous solo exhibitions just wouldn’t have worked, it wouldn’t be discursive. That’s why we decided to show the work on separate screens. We displayed the Aerialist episode hanging from the ceiling with a beautifully designed steel structure; while the episode titled Our Nurses fitted next to Spence’s work that deals with the medical profession. The other episodes were divided according to themes: sociopolitical loss, digital death and the fictional story of the character Genesis, an artist who is dying.

I wanted bears, and I designed them with long arms for hugging, as to embody a sense of support. People respond well to them. Coming from performance practice it is important to me that works have a certain sense of embodiment to them in the gallery space. The tent and bears are made from tie-dyed fabric, which is something I have been doing for a while now. For the show I focused on an inner bodily feel for the fabric, but it’s also transparent and skin-like. The tents were made to create a sense of intimacy for the viewing experience, yet not secluded inside an enclosed space.

What was the impact of making Revisiting Genesis as a project generally on how you think and talk about death and dying, and the fears around those? I understand you’ve made a new piece that’ll go on show in October about your late father—did making the other pieces in the series make that any easier? What was the experience of making that piece like?

Making the work around the death of my father, which is still ongoing, has been incredibly challenging to say the least: watching footage of his last days over and over, and listening to the sounds, has an impact. However, coming out of it now as the film is drawing to a conclusion, I am beginning to feel lighter, and I am feeling the healing aspect of processing his death—which was very fast, it took four weeks, and everything changed following this.

“Revisiting Genesis and the death of my father mark a period in my career where I turned my attention to other aspects of my life other than just art”

I feel that in a sense Revisiting Genesis was almost like a kind of prediction, because living through his dying process, death and post-death is like living through Revisiting Genesis. In terms of my own sense of relative withdrawal, Revisiting Genesis and the death of my father mark a period in my career where I turned my attention to other aspects of my life other than just art in the balance of things.

While some of your work deals with these sort of dark, sad themes, there’s a lot of humour in it too—there are recurring references to custard cream and bourbon biscuits, sharks and the TV series Nurse Jackie, for instance. Can you tell us more about the role of absurdity and humour in your work?

Absurdity is probably the way in which I experience myself and the world most of the time. It’s like a layer through which I view everything. Spiritually and scientifically, we know that what we are seeing as real and solid is not what it is. So the sense of the mythologies that we create, like denoted “linear time” in order to survive as a social species, is absurd really in its limitedness, yet moving in its beauty as we try to make sense of the world.

“Absurdity is probably the way in which I experience myself and the world most of the time”

In terms of humour, I see humour as a survival strategy for many individuals and cultures. So my interest in it is also political. In diasporic Jewishness for example, it plays a huge role. Also humour has always been a great way for me to by bypass censorship (not always!) and other difficult issues in my work, making it more accessible.

You’ve taught at a number of different institutions; what are the most important things you think art students should leave higher education with?

Actually it has been my education work in community setups that shaped my interest in radical education. I ran workshops for years in prisons and community centres, and with various and diverse communities like lesbian asylum seekers with Artangel in 2010, and around three years ago I did a residential workshop with Anna Colin at Yorkshire Sculpture Park looking at the history of the art curriculum in the UK in the past one hundred years. I was particularly interested in Tom Hudson’s archives, who in the 1950s and sixties, pushed art education in the UK from parochialism into an interdisciplinary, hands-on approach that was experimental and in touch with the outside world, looking at things like computer art. This really made me realize how important art education is in shaping the innovative art that we have here, and how little attention we give it as a major player in how contemporary art continues to develop. A lot of it starts in art schools. Increasingly (as I expressed in episode six of Revisiting Genesis, Charles Keene College, Leicester), we are risking taking the soul out of teaching, losing all of this to neoliberalism, led by upper managerial and corporate agendas.