I begin my afternoon in SoHo, dropping in at Team Gallery, which has a show called Mark, featuring work by Erica Baum, Shannon Ebner, Louise Fishman, Al Loving, and Suzanne McClelland. Loving’s paper pulp collages are amazingly painterly, as are Erica Baum’s photographs of half-erased chalkboard marks. All the work here has a playful relationship to art’s history (especially the suggestive gestures of Abstract Expressionism), as in Fishman’s My Guernica (2017), which recalls of course Pablo Picasso’s Cubist apotheosis, and maybe too the black-white-and-red color scheme of Black Flag’s My War (1983). Around the corner, at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, a similar kind of aggressive beauty, interested in intense markmaking, is on view in Haptic Tactics, curated by Noam Parness, Risa Puleo, and Daniel Sander, with work by more than a dozen artists. Laurel Sparks’s quirky assemblage paintings, with beads and pastel colours, are contrasted by Jordan Eagles’s monochromes of human blood and resin. Cassils’s The Resilience of the 20% (2016) commemorates a performance in which the artist deformed 2,000 pounds of clay with their body, as well as the 20% increase in murders of trans people worldwide in 2012. Dented and crushed, shaped, by punches, kicks, knees, and so on (Cassils is also a bodybuilder and martial arts practitioner), the object is a formalist demonstration of process and aesthetics, as well as a moving palimpsest of catharsis.

“Compared to the fulgent mixed media, installation, assemblage, and assorted weirdo arts in SoHo, much of the work in Chelsea now can seem reserved and pensive.”

Hopping on an A/C/E line train a few blocks away at Canal and Thompson, I ride it two stops uptown to 14th Street and eat lunch at The Butcher’s Daughter, a few blocks south at Hudson and Bank Street. They’ve got delicious light fare including salads, sandwiches, and juices (which they will also add a bit of liquor to if you’re not trying to be too too health conscious). Nearby is White Columns, the storied NY non-profit institution of art and music. Their location at 13th Street has closed and their new location at Horatio Street has not yet opened. They currently have an online exhibition, Feel and Rhythms, curated by Ashton Cooper, with paintings and sculptures by emerging artists such as Nikholis Planck, Simone Meltesen, and Sarah Zapata. Zapata is also included in Haptic Tactics.

- Dario Escobar, Lines of Flight, 2018. Installation view Photo courtesy of Josée Bienvenu Gallery and the artist. Credit to Guillaume Ziccarelli

Compared to the fulgent mixed media, installation, assemblage, and assorted weirdo arts in SoHo, much of the work in Chelsea now can seem reserved and pensive. At Paula Cooper, the exhibition in their main space juxtaposes photographs by Bernd and Hilla Becher with sculptures by Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt. Across the street, at Josée Bienvenu, Guatemalan artist Darío Escobar refers to Andre’s sculptures with similar works of large wood beams balanced precariously on glass Coca-Cola bottles. The sculptures appear to float reverently, but also call attention to the lasting effects of the export of cultural signifiers (high and low) to places that the United States formerly imagined as being within its “sphere of influence” (read: dominion). Escobar’s paintings—especially those made with traditional Mayan materials such as cinnabar, amate paper, and Maya blue pigment—are beautiful, and use disrupted forms reminiscent of Ted Stamm’s paintings at Lisson on 24th Street. Other shows of geometric abstraction of note can be found at David Zwirner

(Stan Douglas’s DCT prints), at Garth Greenan

(Paul Feeley’s stain paintings), and at Matthew Marks (Martin Barre, whose simple, scrawled paintings surpass his many contemporary imitators).

At Gagosian’s 21st Street location is perhaps one of the most beloved show of this season. I can’t find the quote, but someone asked why museums can’t do retrospectives as good as Cy Twombly’s In Beauty it is Finished: Drawings 1951–2008. The show is huge and chronicles a lot of work, some which remained in his studio after his death in 2008, others on loan from collectors. A catalogue is forthcoming with an essay by David Anfam, who I guess has lived down the shame he brought on himself during the Knoedler forgery trial just a few years ago. It is paired with a set of paintings and drawings at the gallery’s uptown location, including the ten-part Coronation of Sesostris series, some preparatory drawings thereto, and a quadriptych timeline painting by Twombly from 1968.

“Chelsea isn’t, obviously, all sage abstraction. Several shows feature photography and video in really emotionally resonant ways.”

It’s a lot to take in all at once, but there’s good coffee at Trestle or Bottino, both on 10th Avenue at 24th Street. Bottino is a kind of Chelsea staple that provides much of the food necessary to keep the local gallery staff working on any given day.

Chelsea isn’t, obviously, all sage abstraction. Several shows feature photography and video in really emotionally resonant ways. At Gladstone’s 21st Street location, Cyprien Gaillard’s Nightlife (2018) is a mesmerizing and simple 3D video with images of foliage swaying and shaking in the night in three different cities around the globe. The stunning deep greens, bright pinks, flashing whites, and purple blacks of the erogenous-looking cityscapes is backed with a version of Alton Ellis’s rocksteady song Blackman’s Word (1971). In part, the video is intended to reflect on the life and career of the Olympic runner Jesse Owens, though those connections are not very clearly elucidated by the video itself.

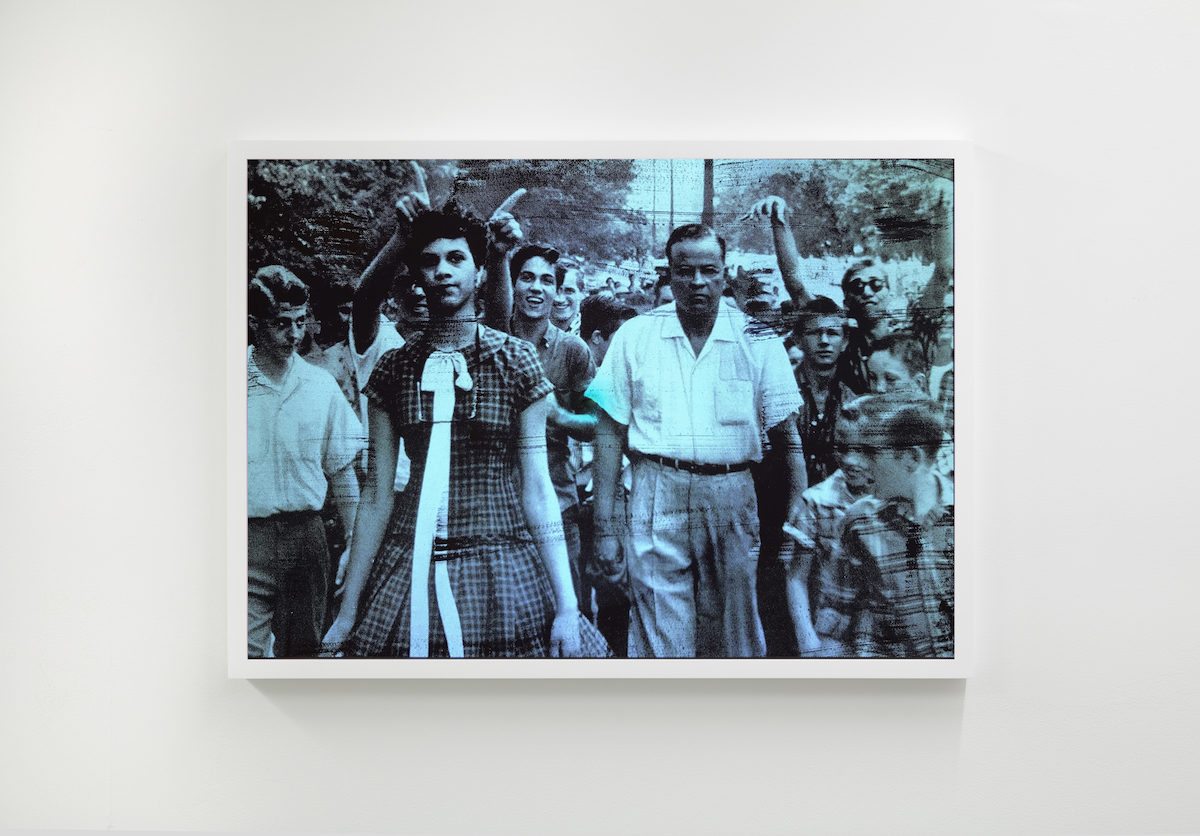

- Hank Willis Thomas, What Happened That Day Really Set Me on a Path, 2018 (with and without flash)

Jack Shainman has a show by Hank Willis Thomas, with work in both their 21st and 25th Street locations, called What We Ask is Simple. Both have very strange and sad pictures, which feel especially timely: historical photos from the Civil Rights movement, the American Indian Movement, Nazi resisters of the 1930s, printed in a special ink on painterly reflective surfaces and displayed in low light. What the viewer sees with their naked eyes is gestural abstraction or a photo severely cropped on a large picture plane. But if one takes a flash photo, a complete photographic vignette briefly appears under illumination: Elizabeth Eckford of the Little Rock Nine walking suavely in her sunglasses is suddenly revealed to be pursued by a vicious mob of segregationists. August Landmesser, a solitary figure in a large white plane with his arms crossed, is transmogrified into a lone silhouette surrounded by saluting National Socialists. An American flag is revealed as a weapon wielded by a segregationist in Boston in 1976, about to be used to stab or beat a young black lawyer in front of City Hall there. The way that photography illuminates the occlusions of acute civil failure is powerful in a way that makes words insufficient, though the gallery has provided a description of the events documented in the images selected by Thomas. In part it appears that what is being asked is both being requested visually, and is a please for visibility.

Finally, at Metro Pictures, Year of the Dog, Oliver Laric’s first show with the gallery includes three sculptures and a short video. He first came to my attention at the 2015 New Museum Triennial and I found this new material very curious. It comes from a similar vein of imagery, with cartoons of people and animals morphing into one another in a montage of clips that feels entirely modern while drawing from older pop source material, such as Bambi (1942) and The Land Before Time (1988). Titled Betweenness (2018), the video addresses the ambiguities of identity that are particular to cartoons—e.g. talking animals and limbs that stretch or mutate—and those ambiguities that are found in an era when humans, at least in the developed world, have taken immense territory in the ways that they express and inhabit their own identities, how people manifest what is interior.