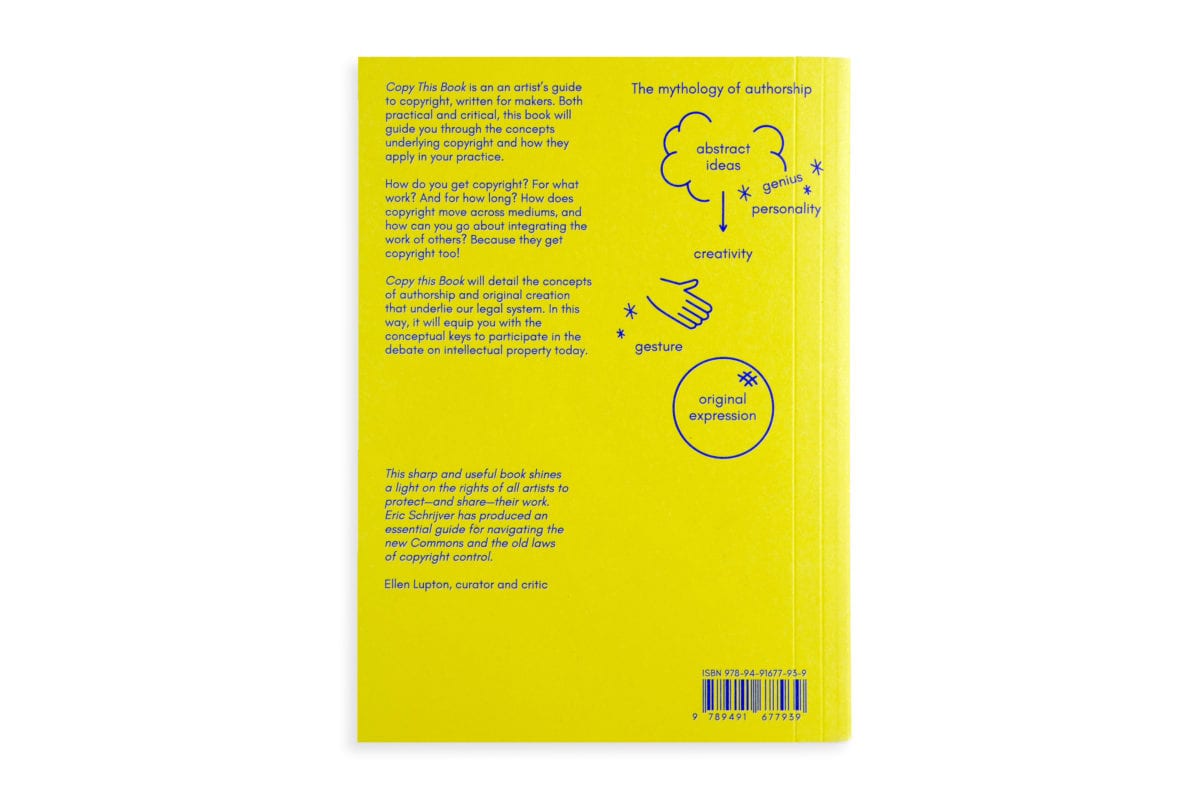

The book is squarely aimed at those making art, mixing legal nous with practical tips and real world advice. The author has kindly let us republish an excerpt from the book, which has been edited for brevity.

In Love With the Copy: Visual Arts

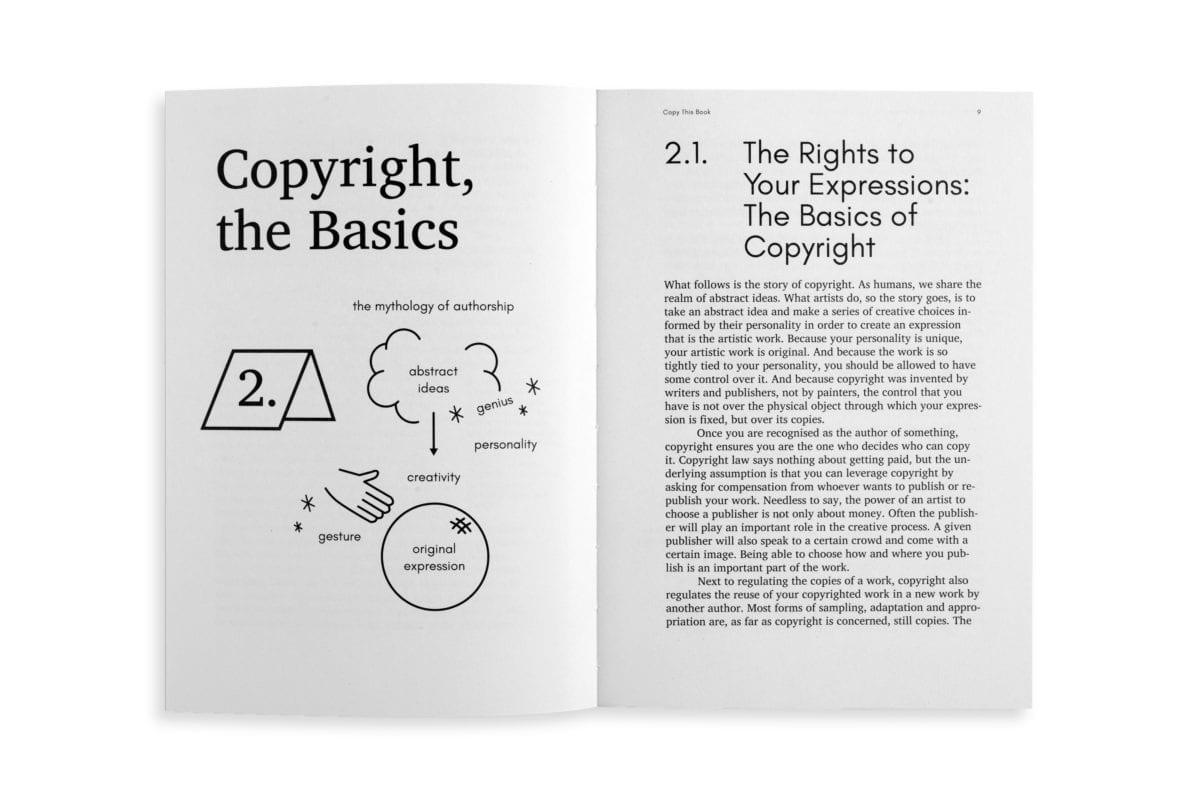

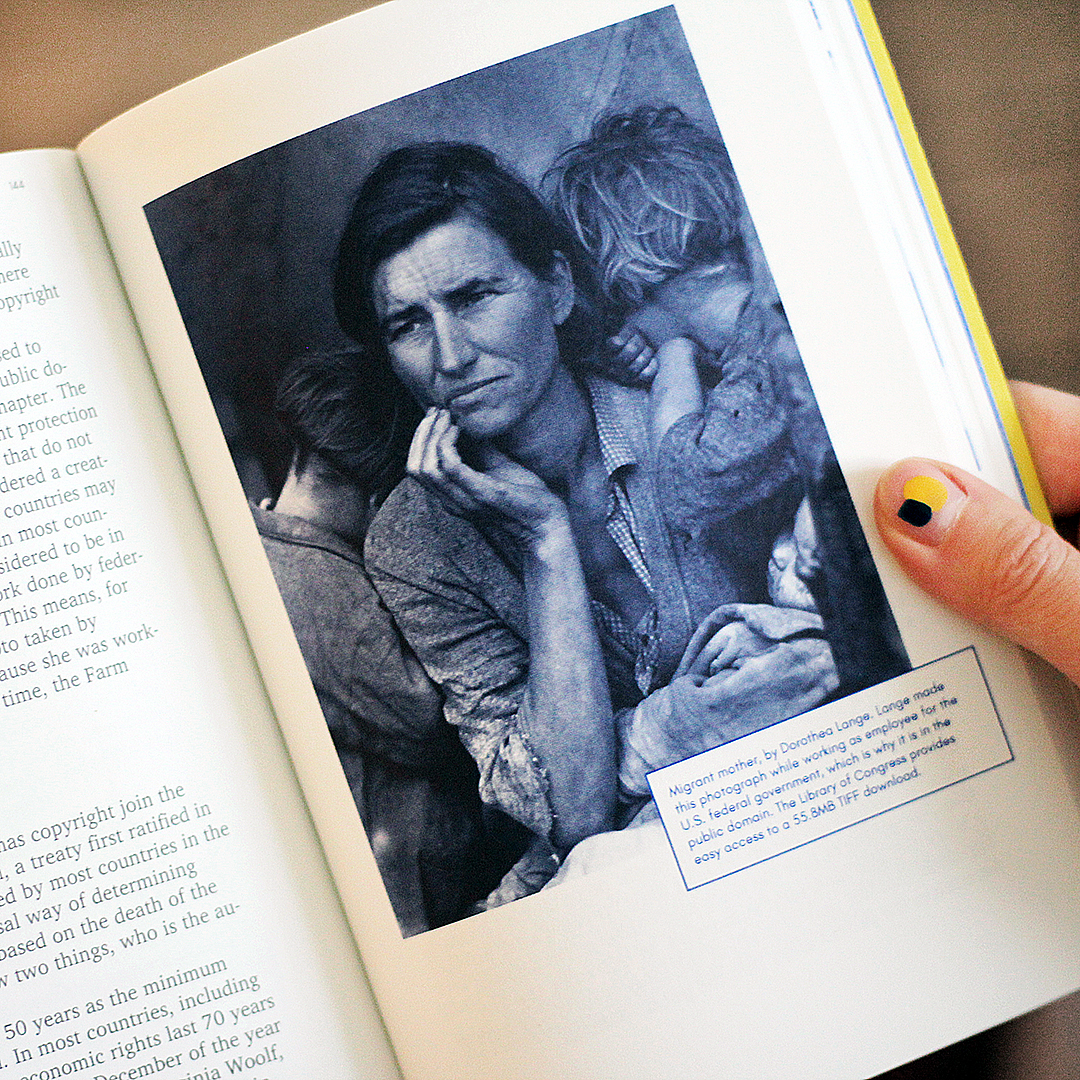

Compared to previous generations, artists are surrounded by an extraordinary number of images from different times, made for different purposes and by both professionals and amateurs. How enticing, then, to make use of these images as motifs, starting points, illustrations, sources? A number of art movements from pop to appropriation to the figurative painters of the 1990s did exactly this. The bad news is that what is common artistic practice is prohibited by copyright. Without permission of the author, you cannot copy an image.

But I Didn’t Make Money

A common misconception about how copyright works is that if you make no money there is no infringement. Legally, this is false. A judge may only take into account the revenue generated when determining the height of the damages owed. In the United States, the situation is slightly different. Whether or not a work falls in the category of “fair use” is in part determined by whether there are monetary gains.

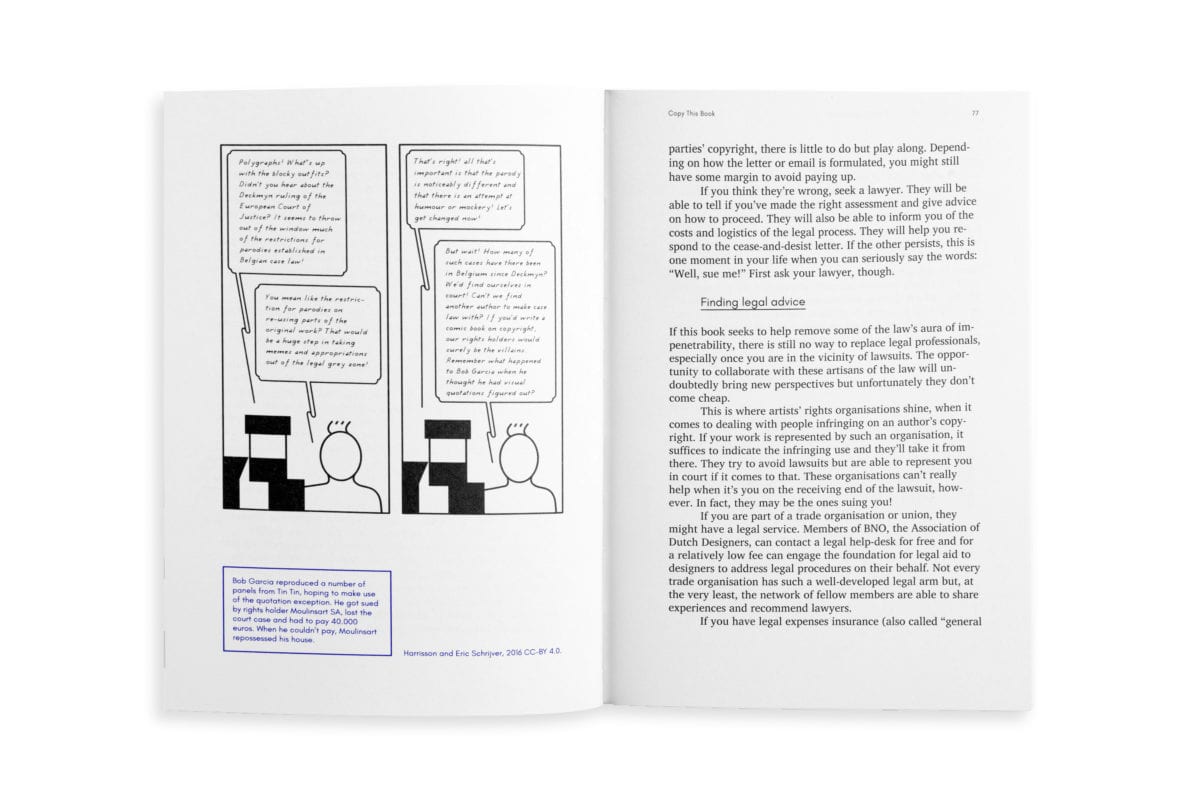

In practice, the risk of lawsuits does get bigger the more money you make as an artist. On the one hand, this is because you lose some of the goodwill associated with being young and struggling. After all, lawsuits are filed by human beings, often artists themselves, who are sensitive to other arguments than those that are strictly legal. More importantly, with fame comes more visibility, which increases the chances that the person whose work has been appropriated will find out about it. Art Rogers, the photographer who successfully sued Jeff Koons, discovered Koons’s sculptural appropriation of his photograph when the latter reached the front page of the Los Angeles Times’s Sunday calendar

.

So if, like most artists, you are working, exhibiting and selling within a relatively restricted social sphere, chances are you can use existing images without running into problems. That said, the security through obscurity that protected the majority of visual art from lawsuits in the past is eroding because of the Internet. Pictures of an exhibition visited by several dozen people will linger online. Reverse image search engines make it possible for rights-holders to find out about reuses.

- Wikipedia took down these illustrations (CC-BY SA) by user Rama, not because of their explicit content, but because of the suspicion that they might have been based on existing photographs.

But I Made Something New

Many artists share a common intuition that it’s not bad to copy someone as long as you make something new out of it and especially if you credit the original. Unfortunately, copyright law does not care. A small number of exceptions notwithstanding, it is not possible to copy an existing work without asking permission and that’s true even when you use it to make something new.

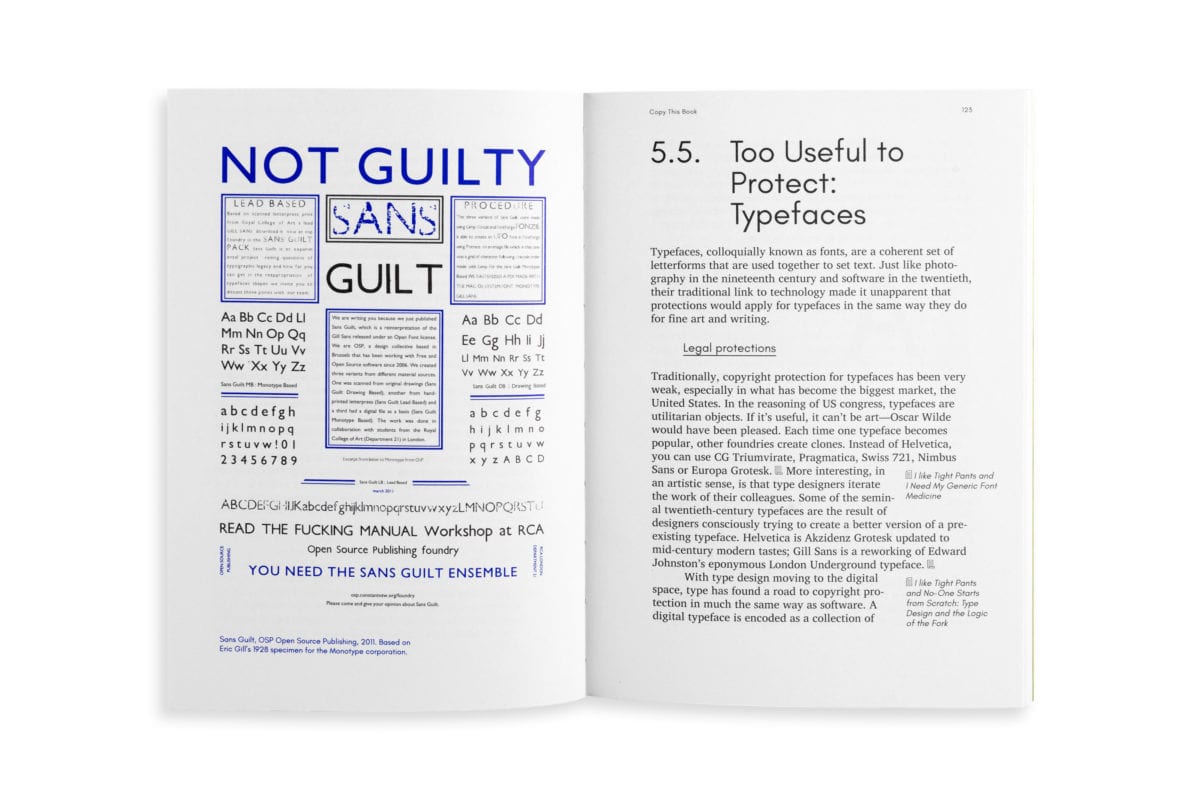

So, what is a copy? The way in which copyright works is to protect specific creative expressions. Once you’ve made a photograph or a drawing, no-one can copy or even adapt it without permission. But that rule does not apply for the procedure or style with which you made the image. That’s why every historical period eventually finds itself expressed in a Photoshop filter. In other words, it’s no problem to make a work in the style of another work, you just can’t copy. The forger Geert Jan Jansen got so adept at imitating the style of Karel Appel that Appel himself certified a number of Jansen’s works thinking he himself painted them. Since getting caught, Jansen now exhibits paintings “in the style of” the artists whose style he inhabits.

So, when is a copy still a copy? If I make a drawing after a photograph, for example, do I still need permission? Most probably, yes. A drawing of a photograph is considered a derivative work as long as the form of the original is still recognizable in your copy.

Being Copied

Chances are that as a visual artist you don’t primarily depend on copyright for income. Both commissioned works and works sold through a gallery are part of a market modelled on physical artefacts. Within the gallery system, even the market for multiples like digital movies and prints of photos is regulated through certificates of authenticity rather than through copyright licenses. Your secondary income is more likely to come from related work (e.g., teaching, designing) and grants than from copyright licensing. Given all that, how do you handle being copied?

What’s important to know is that copyright grants you the discretion to figure it out on a case-by-case basis. That means you don’t have to be as strict as the letter of the law. If you’re being copied and you’re OK with that, you are not obliged to do anything. When Marlene Dumas copied a photograph by Andre van Noord, he was honoured (it probably helped that they knew each other and Dumas had bought a print). You can also choose to exert only part of the powers the law allows, for example, by asking to be properly credited without asking for damages. In some cases, the copy presents a real commercial interest. Fast fashion retailers like Zara and Forever 21 play loose with copyright and habitually include illustrations they find on Tumblr and Instagram.

If you’re interested in creating additional income by licensing your work, an option to consider is joining an artist rights association. Whenever someone is interested in licensing your work, you refer them to the organisation and they negotiate the contract for you. Additionally, in many countries there are collective licensing agreements, which can mean artist rights organizations collect fees and levies from libraries and companies that make photocopies or from consumers who buy blank hard disks and mp3 players. It’s only through joining a rights organization that you have access to a part of this money. Finally, they can be invaluable when you need to deal with infringers because you don’t have to pay fees for legal advice beyond those of your membership.

Copy This Book by Eric Schrijver is out now, published by Onomatopee

VISIT WEBSITE