Festival photography usually falls into a few “content”-friendly cliches: the lairy fluoro EDM bro sporting those thoroughly depressing symbols of late capitalism, the shuttered EDM shades; hot babes in bikini tops on someone’s shoulders; some gurning dude covered in mud/possibly shit; Insta-preemed festival chic purveyors in something to do with crochet and Hunters who still worship Sienna Miller; the occasional middle class Latitude family, just having a lovely time at a make your own mandala cupcake workshop.

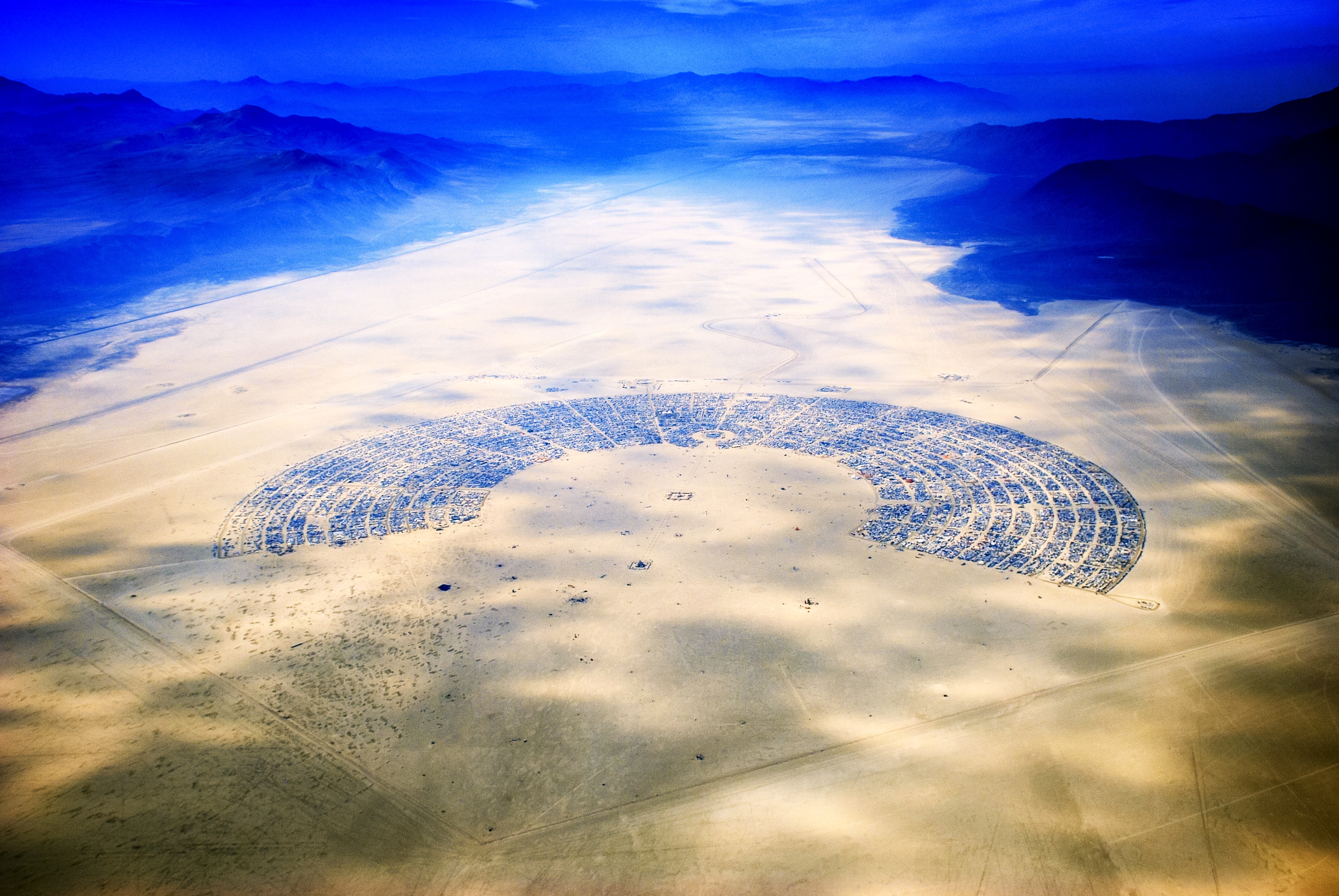

“At once, the viewer is above this monumental place, the Nevada desert but is also made aware of this place’s formidable power”

But Burning Man is a slightly different terrain, not least because it’s slap bang in the middle of a desert rather than a field paved with drizzle and Carling. Burning Man also seems to be at pains to not be called a festival at all. (In one curt email I received for a different piece, I was told in no uncertain terms that “Burning Man is not a festival. Black Rock City is a city built by and for its participants, and the week in the desert is one part of a year-round, global community and culture.” So that’s that.)

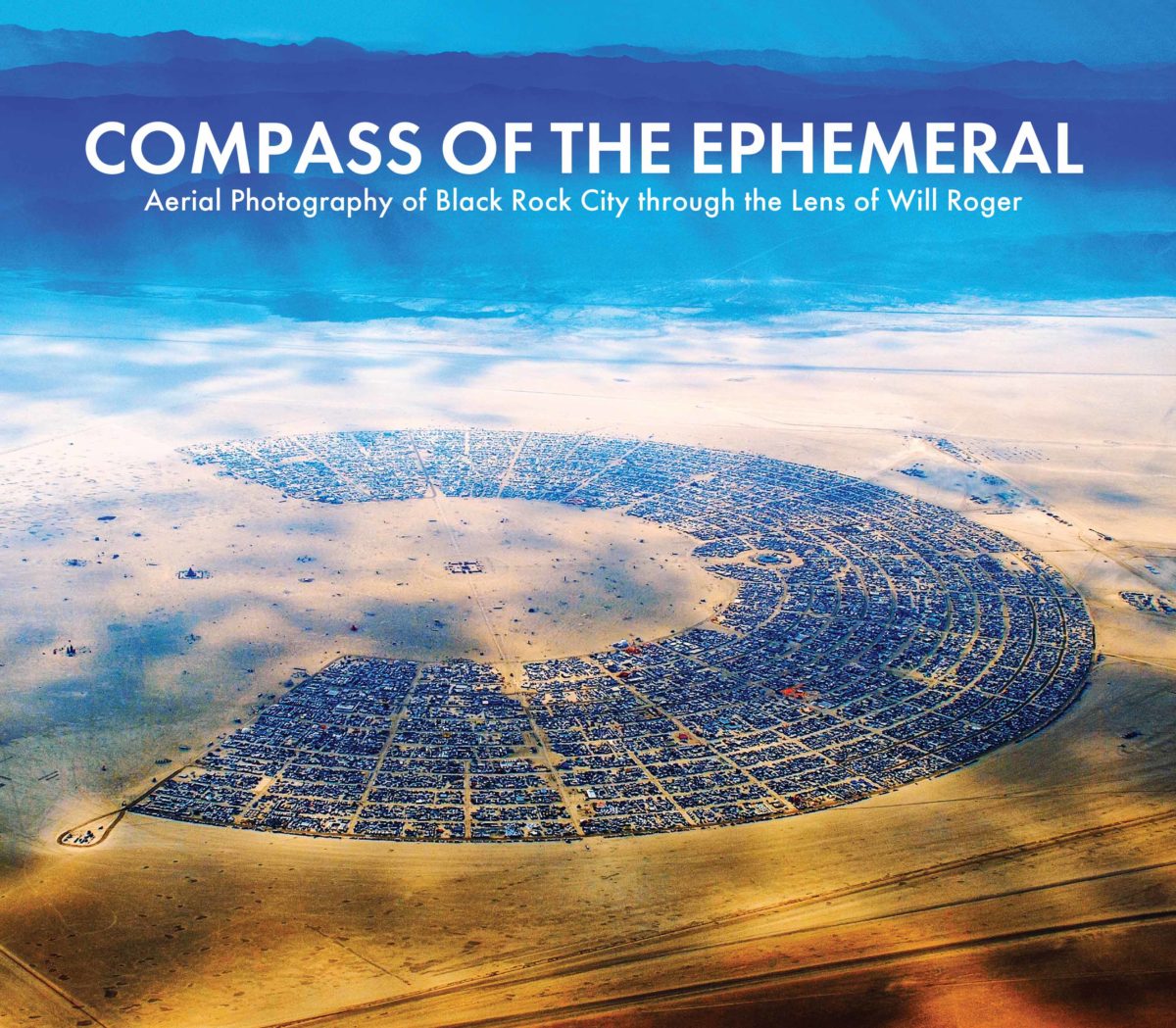

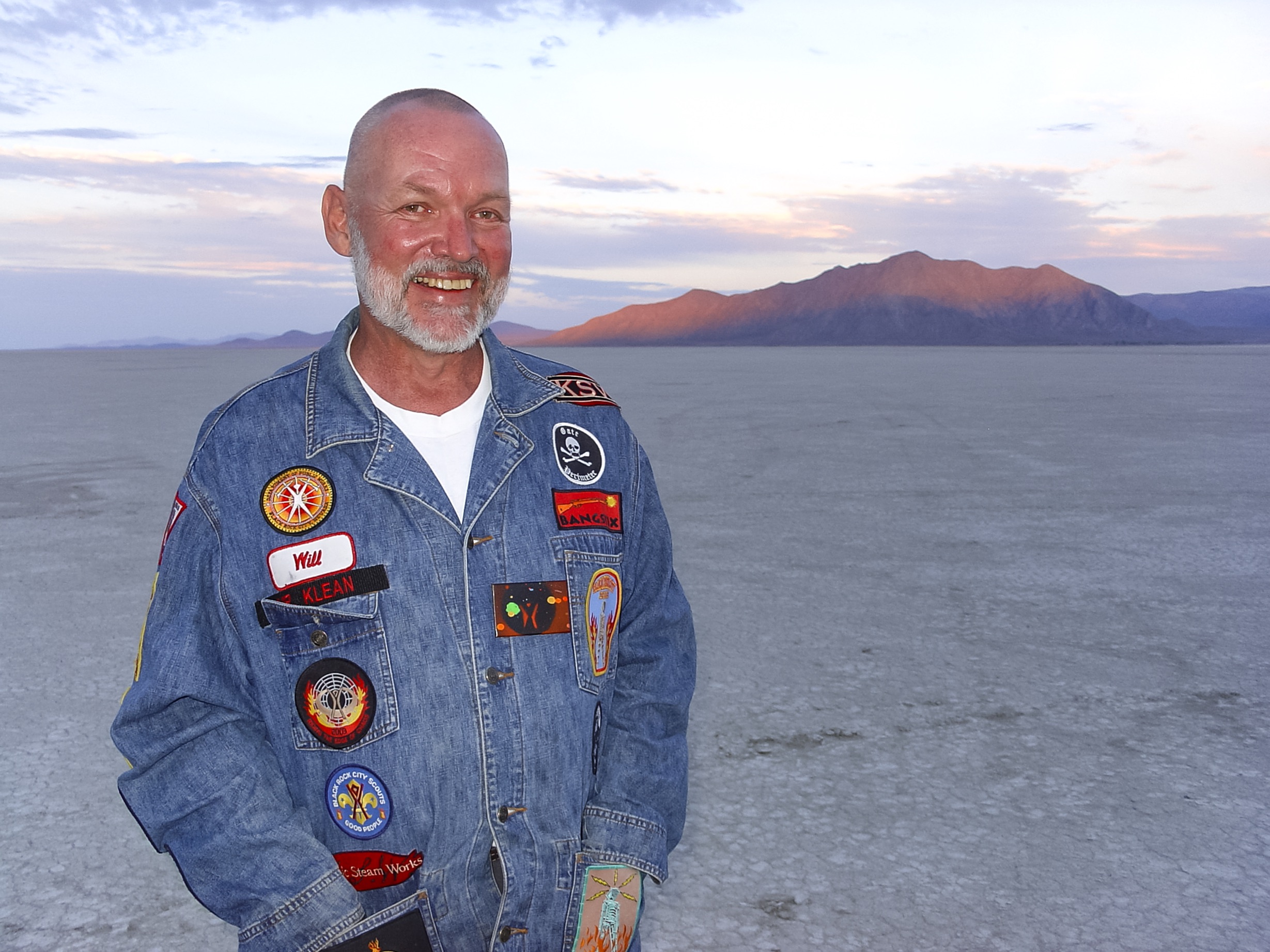

As such, it’s little surprise that a new book of photographs of Burning Man entitled Compass of the Ephemeral takes a rather different approach, for the most part eschewing shots of festival-goers by presenting mostly aerial and drone images shot by Will Roger, cultural co-founder of Burning Man. The concept of the book was to provide a timeline of sorts, an overview that shows the ever-shifting landscape both physically and more widely in its reach and audience.

“The aerial view is a unique perspective,” writes artist, teacher and environmentalist Rosa JH Berland in the book. “We are able to see the great land’s edges, furrows and peaks. At once, the viewer is above this monumental place, the Nevada desert, but is also made aware of this place’s formidable power, and awe-inspiring allure.”

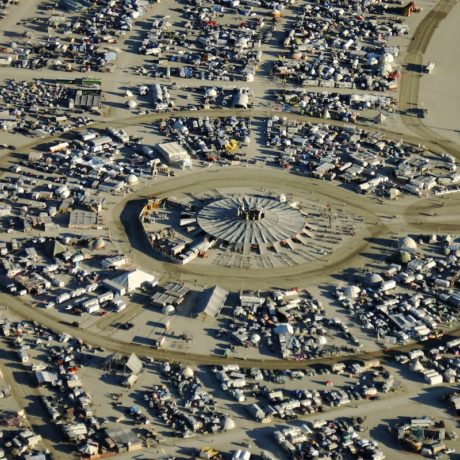

What’s striking in the imagery is the dichotomy between the harsh desert terrain and vast swathes of untouched landscape, and the order of the lines and formations of the camps themselves—just as a Londoner used to winding, shimmeringly nonsensical snaking streets looking at New York from above with its tidy grids, there’s a weird sense of a space that feels as though it could only have been constructed by a meticulous Brobdingnagian overlord.

“The smell of the dust in one’s clothing and equipment will immediately evoke a memory”

The first Burning Man took place in 1986, and in just a decade had more than doubled in size so that by the mid nineties it hit 10,000 people. The original infrastructure simply couldn’t take it, and a decision was made to create a “formal grid city” as Burning Man co-founder Harley K Dubois puts it in the book, “and with it the characteristics of a community began to emerge… Immediately, people began to gather in more intentional ways. I was able to place loud camps away from quiet ones. Art was moved out in front of our camping areas. Driving was banned…A camping trip transformed into a city.”

The design of said city was largely based on the designs of Rod Garrett; and as the years went on, it was modified to allow for the increasing number of people’s needs, with shared plazas added for “gathering space” and the later addition of a Kids Camp. The vast changes are perhaps only evident in such large-scale images as presented in this book; as is the shift the site has had to make a number of times over the years due to stipulations from the Bureau of Land Management.

Today, Burning Man brings in more than 70,000 people; and this monumental scale is even hard to grasp from an aerial perspective. For comparison, that’s around the same as the entire population of Barnsley.

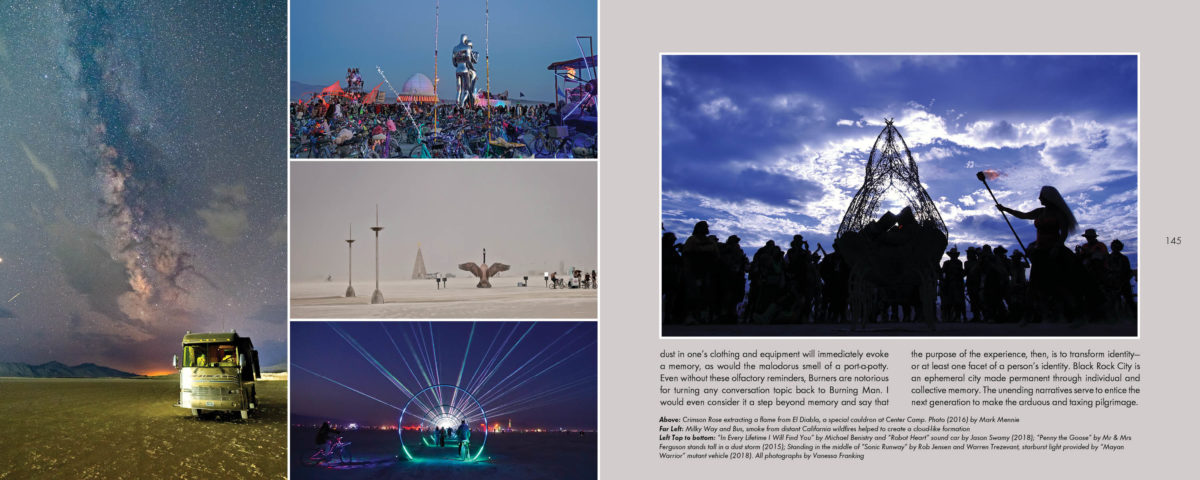

Compass of the Ephemeral also includes a series of essays discussing the physical, cultural and artistic context and impact of Burning Man; which as anyone who’s ever spoken to anyone who’s been to the event will guess, take on a quasi-religious sense of reverence that’s in turns slightly enervating and deeply fascinating.

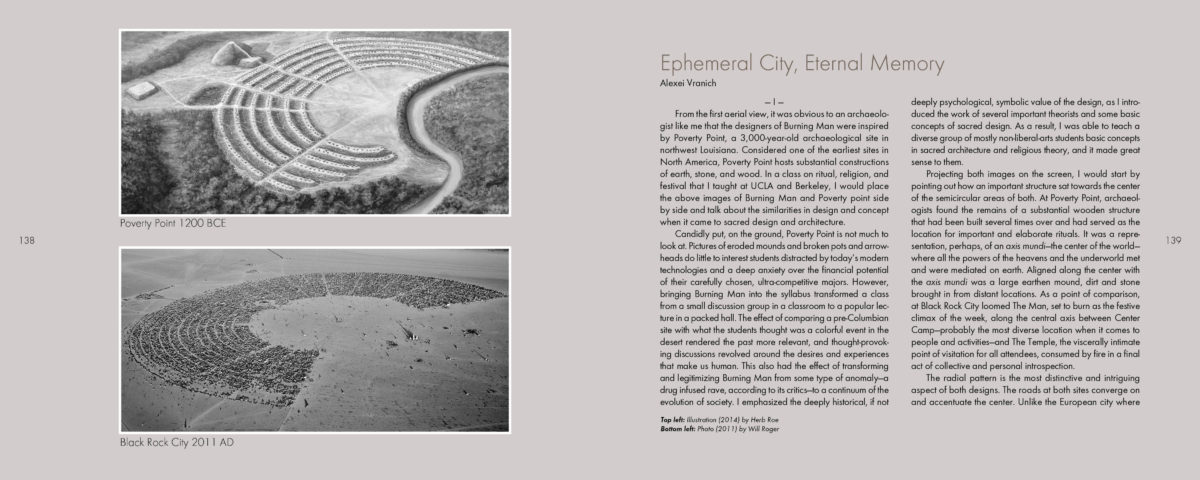

As archaeologist Alexei Vranich puts it in his piece (which compares the site to Poverty Point, a 3,000 year-old archeological site in northwest Louisiana), “The smell of the dust in one’s clothing and equipment will immediately evoke a memory, as would the malodorous smell of a port-a-potty.” (The same could be said of anyone who spent their mid to late teens yelling “BOLLOCKS” and watching the likes of Less Than Jake at Reading Festival). He continues, “Even without these olfactory reminders, Burners are notorious for turning any conversation topic back to Burning Man. I would even consider it a step beyond memory and say that the purpose of the experience, then, is to transform identity—or at least one facet of a person’s identity.”

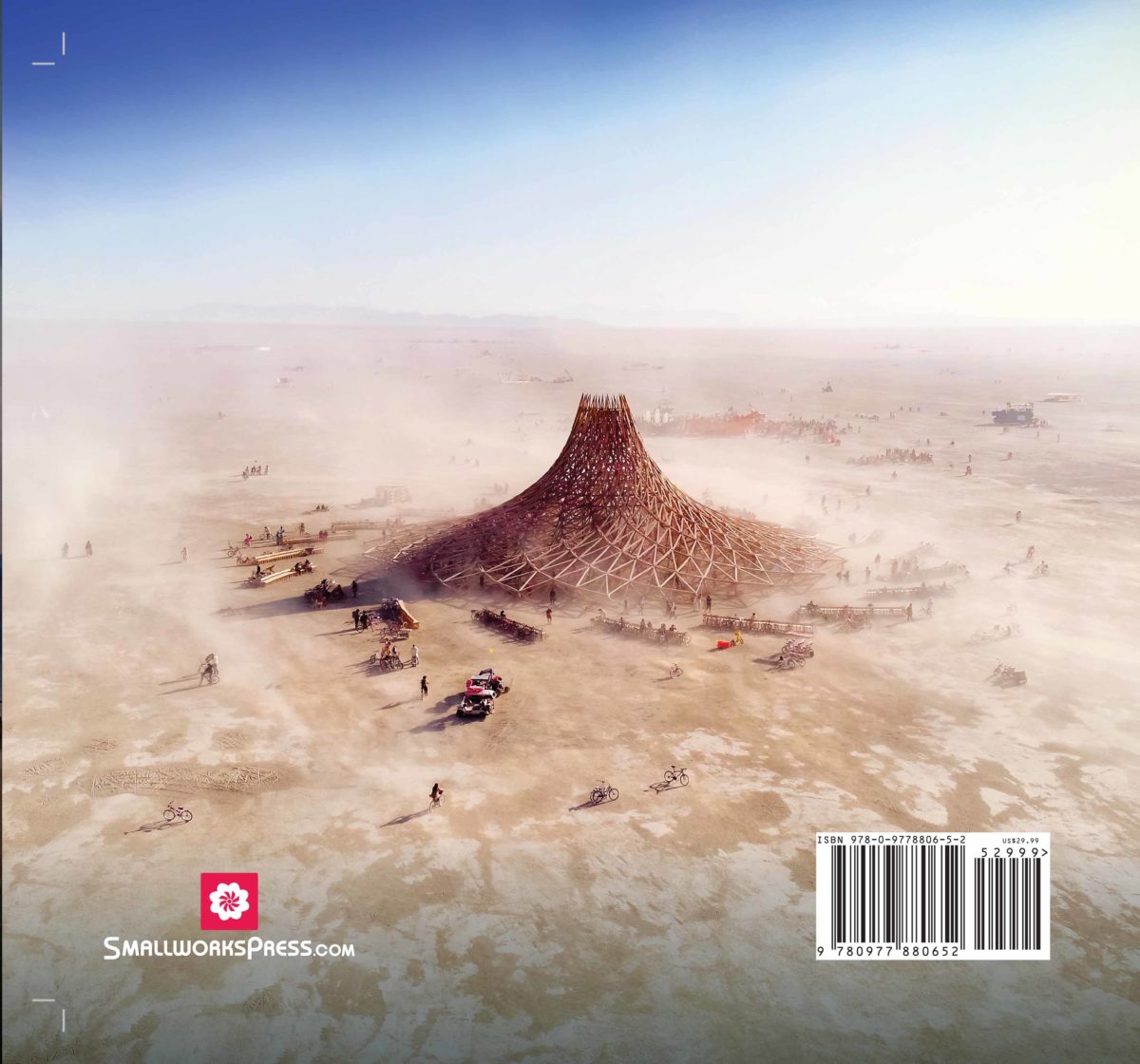

- Smallworks Press Compass of the Ephemeral, cover

Compass of the Ephemeral: Aerial Photography of Black Rock City through the Lens of Will Roger

Published by Smallworks Press on 18 June

VISIT WEBSITE