The arrival of Mungo Thomson’s Mail project in book form comes at a pretty perfect moment. In its exposition of time as a bracketed discrete entity (here, it is an exhibition’s duration), we’re reminded of life as it is now, bracketed by the weeks, or even months, spent in lockdown. Time, in both contexts, crawls—marked by news bulletins, Skype calls as flimsy proxies for human interaction; daily permitted minutes outdoors (for most of us); and in piles of post, in the case of Thomson’s piece.

This book, published by Inventory Press, offers documentation of Mail as it was being formulated in 2018, at The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Thomson asked staff to let their incoming mail accumulate, unopened, during the run of the 2018 group exhibition, Stories for Almost Everyone. The process saw a large pile amass in a dedicated corner of the gallery, forming an art piece in and of itself, which veered somewhere between timepiece, installation, archive and an exposé of museum machinations.

“Exhibition time—a mode of time-keeping that tends to divorce itself from the activities of daily life”

Preceding its outing at The Hammer, Mail had been created twice—first in 2013, at Galerie Frank Elbaz in Paris, then at the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver in 2015. These pieces, however, were undocumented: the piles of mail have been lost to time, redistributed to those they were intended for, and in many cases, put straight into the recycling bin. As such, Mail only lives on in this book, and we have no way of comparing, say, LA’s junk mail with that of Paris. That would have been interesting in itself; a test of our stereotypes around how, say, “capitalist, big and brash” America is compared to “chic, pared-back” France.

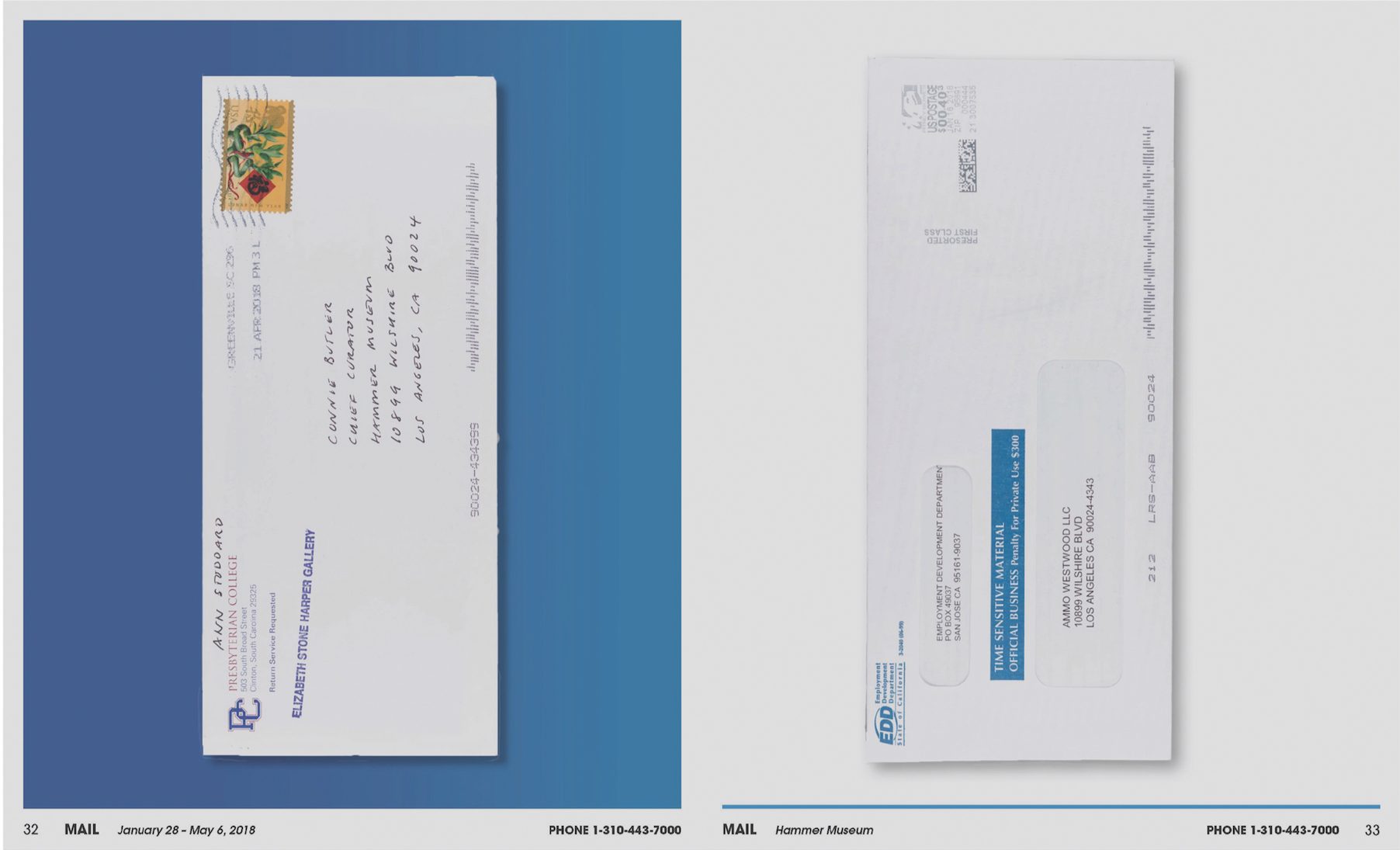

Reproductions are presented as individual photos of each piece of mail. They are all shown uniformly against a bright blue backdrop, with no hierarchical modes of organisation, and no additions or adjustments made by the artist. Things feel serene, and junk almost becomes high-art by dint of its documentation. It’s not “mail art” per se, in that Thomson undertakes no correspondence, he simply gathers it. In its final book form, Mail is simply art formed by an age-old process that gently warns of the waste that comes from running an institution, as it slyly disrupts its modes of organisation and daily functions.

Naturally, over the course of the show the pile of correspondence, junk mail, packages, catalogues and other posted ephemera steadily grew. The book merely hints at this accumulative aspect, however, as we see the individual pieces of post, and occasionally small piles of parcels; but never the final haul.

This uniformity feels clinical, matter of fact, non-judgemental. As Hammer Museum curator Aram Moshayedi points out in his essay for the book, “the contents of this particular mail pile represent the concretisation of the fleeting and ideologically fraught notion of exhibition time—a mode of time-keeping that tends to divorce itself from the activities of daily life.” Since most exhibitions are shown for either weeks or months, a routine forms. This rhythm serves to keep “the administrative wheels turning and the clock of labour ticking toward the next opening,” as Moshayedi puts it, “so that the routinised expectations of a culture-hungry public can remain firmly intact.”