Parenthood has changed my home and its repertoire of smells. Among the most dominant new ones are the funk of a full nappy and the soapy lavender of the sack into which I drop it. For a while after my daughter Athena was born, the scent of nappy sacks seemed to pursue me everywhere. But other aromas now compete with it. For instance, there’s the milk, both breast (a hint of vanilla) and formula (malty). Then there’s Athena herself—the distinctive biscuity warmth of her bundled little body—and her creamy posset, the almond scent of her shampoo, the lingering sandalwood of the detergent in which I wash her outfits.

Pretty much everyone has noticed that smells mark territory, play an important role in attraction and can have therapeutic functions. We understand, too, that they trigger emotions and evoke memories. In all of art, the most famous example of this involves Marcel Proust; whatever else people know about the French novelist, they’re aware that when the narrator of À La Recherche du Temps Perdu eats a madeleine he’s drawn back into his past and recollections begin to pour out of him. It’s not the taste of the shell-like cake that inspires this, but instead the bouquet of the lime blossom tea in which the madeleine is dunked. The power of scent to stir recollection is routinely described as “Proustian”, and for Proust it is the memories that smell calls up, rather than those we choose to retain or summon, that contain the essence of the past.

“Perfumes apart, we still pay limited critical attention to smell. It’s a growth area”

Attending to the smells associated with my daughter, I think about the role of smell in art. Who, I wonder, are the virtuosi of odour? Perhaps, on reflection, there are none. Maybe this is a part of parenthood undocumented by artists. At the risk of stating the crashingly obvious, paintings appeal to the sense of sight, and sculpture to both the eye and the sense of touch; neither can depict smell directly.

We can, it’s true, be shown the reaction to a smell, as well as the image of something we know is pungent. When I look at Raphaelle Peale’s Cheese and Three Crackers or Clara Peeters’s depiction of a half-wheel of gouda, I can imagine their tang in my nose and the flavours that might follow. Or am I being fanciful? Perhaps I just want this to be true. To test what really happens, I stand before Willem Claesz Heda’s Still Life with a Lobster and a Constable painting of a meadow: all I can pick up is the faintly musty smell of museum and the sundry perfumes of its visitors.

There’s a tradition of regarding smell as the lowliest of the senses—and of not just devaluing smell, but also deodorizing history. A common view, espoused by Plato and later by a host of Enlightenment thinkers, is that there is no relationship between the nose and the intellect. According to this broad school of thought, odour is an animal matter, and odoriferous forms of employment or amusement are strictly for the unenlightened.

Yet while, perfumes apart, we still pay limited critical attention to smell, it’s a growth area. At a stretch, I’d argue that modernity denied the very idea that there could be an aesthetics of smell, and that postmodernity has redeemed it.

It is possible to create paintings and sculptures that exude an aroma. Antwerp-based Peter de Cupere has been experimenting with olfactory art since the 1990s. He once took several hundred clown noses into a clinic for children with cancer, before pumping in the toothsome smell of fruit chews. Among his more recent works are scratch-and-sniff oils. One, a homage to Gustave Courbet, captures the crispness of red apples; another, a winter scene, has the eucalyptus smell of cough sweets. He’s even come up with a curious riff on the Madonna and Child

theme, a canvas that has the fragrance of baby powder.

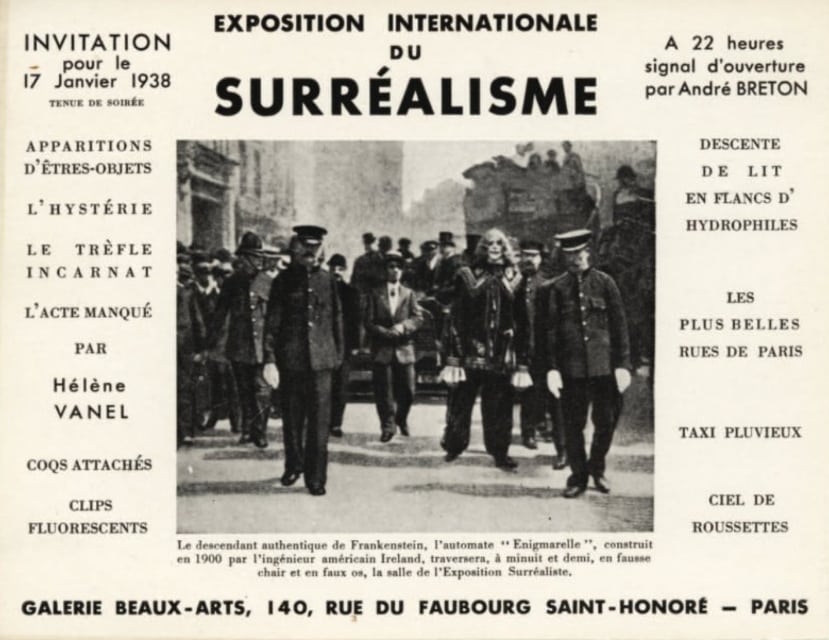

Yet it’s installation art that truly has the scope to engage our sense of smell. Marcel Duchamp was a pioneer, apparently using the aroma of coffee in his exhibit at 1938’s Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme. His example has been seized on by artists such as Takako Saito, a member of Fluxus whose special chess sets required players to use their sense of smell rather than their sense of sight, and Ed Ruscha, whose Chocolate Room, the walls of which were covered with chocolate spread, debuted at the 1970 Venice Biennale, where it attracted an army of local ants.

A more recent instance is architect Kengo Kuma’s contribution to 2014’s Sensing Spaces at the Royal Academy, which invited visitors into a bamboo structure perfumed with a kind of cypress wood used in the construction of Japanese teahouses. In similar vein, Morgan Wong’s That’s How I Used to Know I Have in Fact Crossed This River appeals to the nose to suggest the atmosphere of travelling from Hong Kong to mainland China. Michael Pinsky’s Pollution Pods recreate with acrid vividness the toxic atmospheres of five modern cities, and at each performance of Brian Goeltzenleuchter’s Olfactory Memoirs, when writers recall moments from their childhood the smells they mention are immediately delivered to the audience.

The leader in the field is probably Sissel Tolaas. Born in Norway and now based in Berlin, she has created a paint that contains “micro-encapsulated” aromas, which are activated by touch. Her installations have addressed themes such as fear and decay; she has also made a Limburger cheese using bacteria sourced from David Beckham’s football boots, which was served to VIPs at the London Olympics.

Tolaas’s work is often interested in morbidity, as well as in the “smell identity” of particular cities. I’m guessing that an installation about babies and parenthood isn’t on the cards. Yet I can’t help thinking that there’s a great piece to be made about this relationship and its aromas.

Straightaway I start to itemize them. A just-soiled nappy with its waft of buttered popcorn. The cheese that collects in the folds of a baby’s neck and possesses not the gym-sock stink of Limburger, but something more like a mushroomy brie. The metallic breath of the sterilizer on the kitchen counter. The yeasty whiff of an old plush toy and the sunny scent of apricot after it’s been washed. None of which is to forget the citrus and cardamom bouquet of my gin and tonic, ticking in its glass at the end of a long day.