It’s that time of year again. Our summer suntans are fading, the nights are drawing in and the leaves are turning. The children have gone back to school and the art world has that beginning of term feel. There’s the jamboree that is Frieze art fair, as well as the opening of the Turner Prize exhibition. Two events that have become as synonymous with autumn as bonfire night. But what exactly is the Turner Prize for? And is there any validity in awarding a prize for art? Imagine a year when Picasso, Braque and Modigliani were all competing. Who would you give the prize to then? How can a prize evaluate unique creative voices, one above the other?

“In a world of the social media we seem to crave shock and awe and soundbites”

But prizes have become a ubiquitous feature of modern cultural life, from the Man Booker Prize and the National Poetry Competition to the John Moores Painting Prize. But art isn’t an Olympic sport where timed performances or superior physical prowess will give you a clear winner. In many ways these prizes distort the cultural landscape, simply promoting flavour of the month by curators who, themselves, are trying to find a place in the limelight. In a world of social media we seem to crave shock and awe and soundbites.

First awarded in 1985, the prize, named after the English painter JMW Turner was founded by a group called the Patrons of New Art under the directorship of Alan Bowness. Their aim was to encourage a wider interest in contemporary art and assist Tate in the acquisition of new works. Between 1991 and 2016 only artists under fifty were eligible, but this flirtation with youth was removed in 2017. Usually held at Tate Britain, the prize has tried to counter criticisms of metropolitanism by being staged in other UK cities, but this year it’s back in London.

From the start it needed commercial sponsors. These have included Drexel Burnham Lambert, Channel 4 and Gordon’s Gin. And where there’s money involved, those who invest want value and visibility for that money. And visibility in the art world usually means “controversy”. The artists are chosen based upon an exhibition in which they have shown during the previous year. Nominations from the public are invited but this is largely cosmetic, as the journalist Lynn Barber confirmed when she was a judge in 2006. The process is arcane. The prize is not actually awarded based on the accompanying Tate show, but on the original exhibition for which the artist was selected, and the real power lies with the panel of judges, which includes fashionable curators and critics.

In 1985, although the conceptual group Art and Language was nominated, painting was still considered central enough that the prize was awarded to Howard Hodgkin. This year any pretence that painting is at the forefront of contemporary art has been abandoned. All four artists work with either video or film. Much of my criticism of previous Turner prize shortlists has been the tired reliance on postmodern irony but, finally, this year—a year when we face Brexit, a migration crisis, the rise of the right wing across Europe and a very real threat to our democracy—the art does appear to engage with current events and cock something of a snoop at the financial trillions of international art dealers and collectors. But is it any good? Well, yes and no.

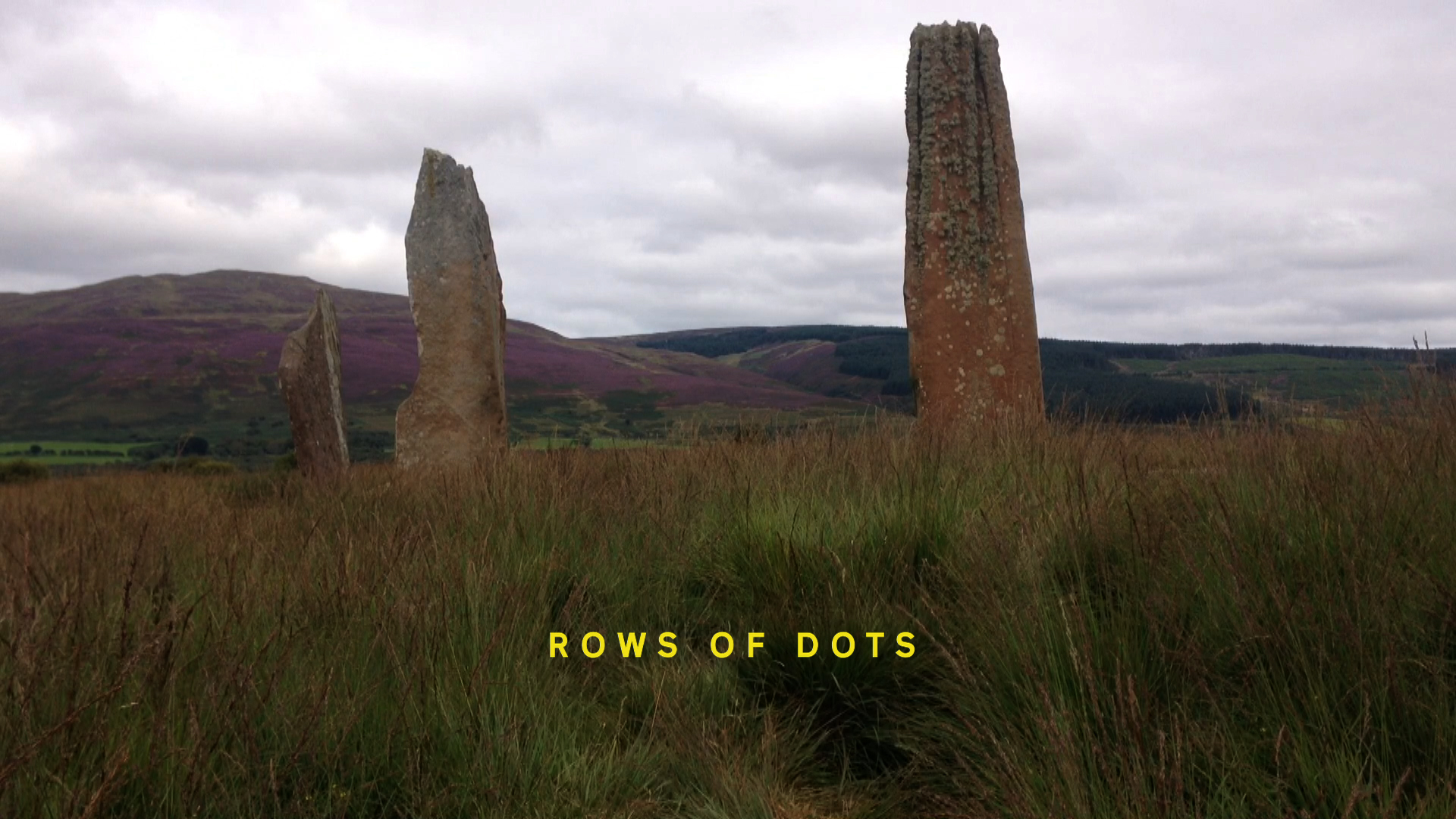

That the work is worthy is not in doubt. But good art also needs to engage the viewer. Charlotte Prodger’s statement that her “installations and performances look at what happens to speech and other representation of the self as they metamorphose via time and space and various technological systems…” made my heart sink. Mainly about sexual identity and queer politics, her rather disconnected ramblings lack any narrative cohesion though she tries to ally them with the Neolithic stone circles and ancient cult of the mother goddess found in her native Aberdeenshire. Whilst there are some lovely painterly shots of rust and purple Scottish landscapes, and her cat, the whole feels like the filmed version of a rather over-complicated dissertation.

The same could be said of Luke Willis Thompson’s 35mm Kodak Double-X black-and-white film, that gives a whole new meaning to the word slow. At thirty, he is the youngest nominee. His Autoportrait was based on the shooting of Diamond Reynolds’ partner Philando Castile by a police officer during a traffic stop in Minnesota. Also showing is his filmed study of Donald Rodney, entitled _Human (1997

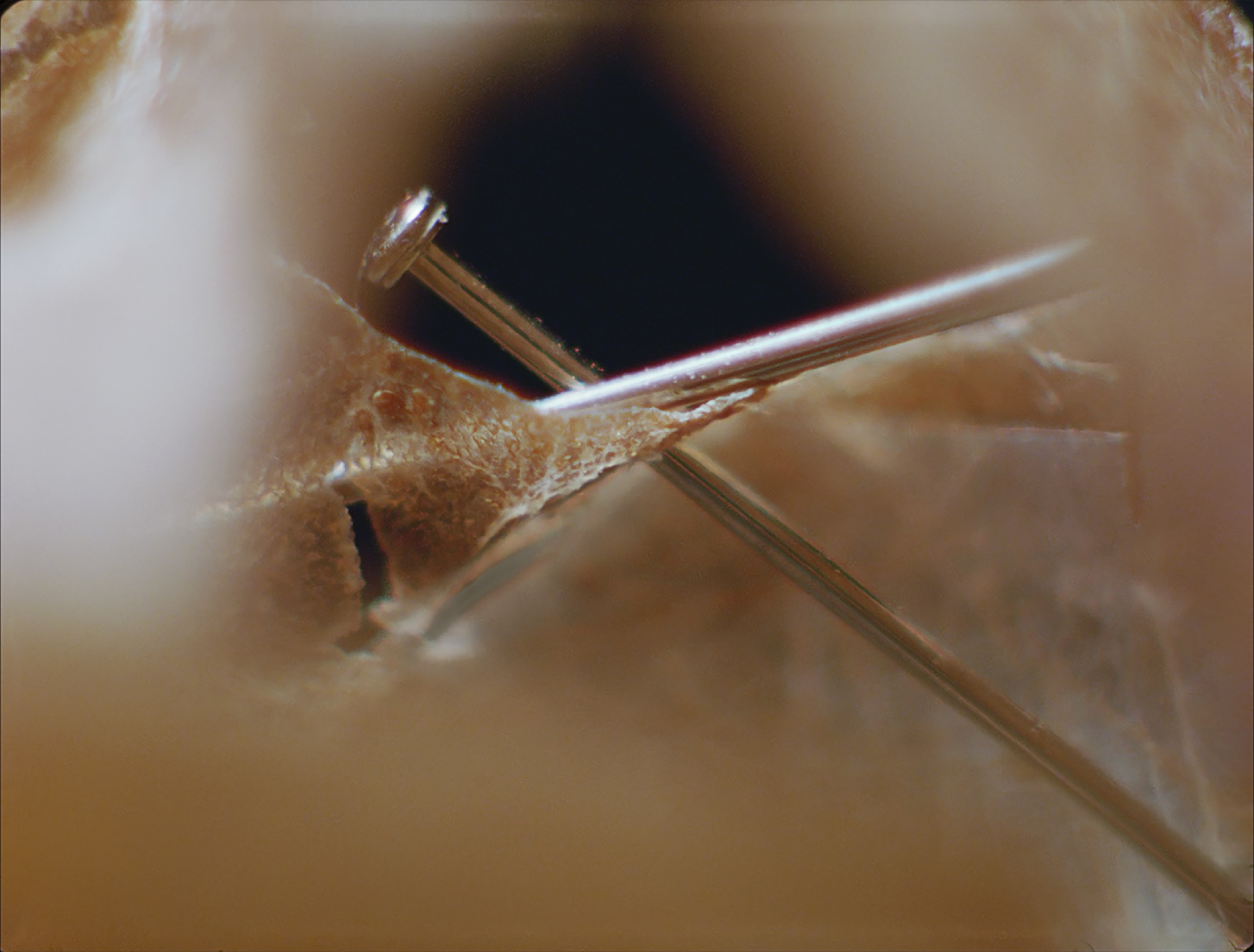

). Rodney was undergoing treatment at King’s College Hospital for sickle cell anaemia and, before he died, made a small architectural model of a house from his own skin held together with dressmakers pins. This can be seen at the beginning of series of the ten-minute films—we see it from every angle. Then Willis Thompson hones in on the silent faces of his protagonists who seem, in some way, to be bearing witness. Their gazes are intense as painted portraits. But the whole is arcane and lacking in narrative connections that might grab the viewer.

The other two works are more direct. Forensic Architecture is a fifteen-member collective of architects, investigative journalists, software developers, scientists and filmmakers based at Goldsmiths in South London. Their aim is to use technology and art to uncover various human rights abuses around the world. Here, together with the collective Activestills, they’ve attempted to unravel official statements about the events of 18 January 2017 when a nighttime raid by the Israeli police on a Bedouin village in the Negev/Al-Naqab desert resulted in the death of two people. It’s a powerful and shocking piece but I question how elastic the definitions of art should become and whether this would have been more suited to a documentary film award.

For me, the work by the British-Bangladeshi artist Naeem Mohaiemen is the most satisfying. His first fiction film, Tripoli Cancelled, follows the daily routine of a man who lived alone in an abandoned airport for a decade. Wandering among the detritus of this empty building in a crisp tan suit and white shirt is like watching someone lost amid the shards of the twenty-first century. Picking up a phone in a smashed phone booth in an attempt to call his wife, he is unable to get through and tells the operator that he’ll try again the following week. Then sitting on the steps of a frozen escalator he quietly sings Never on a Sunday as a tear rolls down his cheek and he lights up a cigarette. With poetic sensibility Mohamiemen suggests a sense of dislocation and the plight of refugees trapped in stateless limbos. Call me sentimental, but I had a lump in my throat.