When searching for the definition of the term “beauty”, its association with women immediately and plaguily stands out. Albeit not surprising, to acknowledge how beauty, pleasure and desire are linguistically and thus culturally entangled opens up a space for further inquiry into the historic construction of beauty standards and reflection on the hidden structures of representation toward gender, race and age. This is the framework where the group show The Blush Upon her Cheek at Studio West Gallery sits. Curated by Bella Bonner, it sees the work of contemporary artists Leo Costelloe, Florence Reekie and Ki Yoong respond to the Restoration Court painter, Sir Peter Lely’s Windsor Beauties (1660s). On display at Hampton Court Palace, this set of eleven portraits depicting ladies of King Charles II’s court plays for the artists as a means to examine the problematics entrenched in the cultivation and appreciation of beauty and the timeless struggle to attain inherently inaccessible standards.

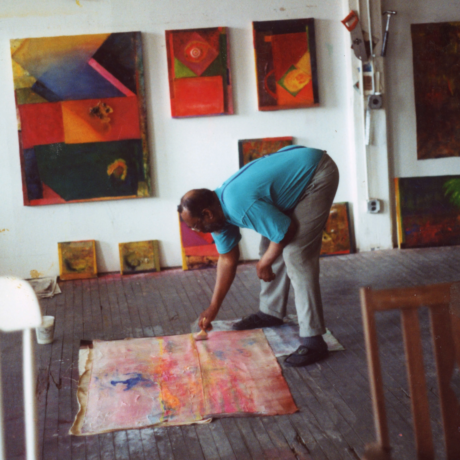

In the gallery space, the viewers find themselves immersed in an intimate, almost domestic environment. It is through fragments of voluptuous drapes, uncanny objects and tender portraits that a cinematic and vibrant scene is constituted. Whether at first one might feel to be the ambiguous voyeur of an imminent ritual of preparation, once their eyes are met by the warm, open amber gazes of Yoong’s portraits, they realise they are welcome to join the process of beautification. The canons of such a process remain intentionally ambivalent as the notion of beauty unfolds through the works of the artist trio. Starting from this ambiguity, my interview with Costelloe, Reekie and Yoong then morphed into a horizontal conversation spanning from the position of their practice within the contemporary cultural scenario to the pressure that exists between artistic freedom and the commercialisation of art.

Maddalena Iodice: Today is the show’s opening day, and also the first time you guys are meeting all in person. How did the show and the concept it delves into come about? Was it a prompt from Bella or an angle that came together as you started to discuss?

Ki Yoong: Well, Bella brought us together as she sensed our work had a synergy and spoke to one another.

Florence Reekie: I admired both of your works prior to the show, so it felt like an amazing moment of synchronicity!

Maddalena Iodice: As you walk into the space, you find yourself welcomed in an intimate and familiar environment where, quite cinematically, through the presence of uncanny objects, drapes of voluptuous fabric and tranquil gazes, a whole scene is constituted.

Leo Costelloe: Yes, there is an element of domesticity, I think, which is probably conveyed by the materiality.

Ki Yoong: Looking around, something that I notice about all of the artworks is that they all feel like fragments, like snippets that pick up on the narrative of the other works in a way. Both mine and Florence’s pieces are kind of cropped, and the elements of some of Leo’s sculptures feel like they’re part of something else outside of the picture frame, which kind of threads a narrative throughout all of the works.

Leo Costelloe: I think the scale brings you in. It feels very intimate. With Ki’s paintings, for example, you’re sort of reaching in…

Maddalena Iodice: The body moves interestingly within this space. Often, when navigating an exhibition, because of the installation structure, we tend to look passively at the walls. Here, instead, the spectator is invited to go closer, crouch down and stand up again…you are literally asked to move.

Leo Costelloe: Yes, there are lots of similar incidences… Ki’s ribbon on the framing over there (Wyvern, 2024) that is such a nice little moment.

Maddalena Iodice: Looking at the artworks you produced, it feels like a process of cross-pollination happened among the three of you. Tell me a bit more about the conversations that generated the show.

Ki Yoong Our conversations really spanned from generating the theme for the show to touching base on the work that we were making.

Florence Reekie We had initial, very early conversations, and then as we started working, it felt like we were going off and doing our own thing, but it would be inevitable that there would be some crossover in the narrative.

Ki Yoong: And I guess the thing that was anchoring it all together was the Windsor Beauties.

Florence Reekie: I think Ki, you came up with the *Windsor Beauties theme.

Ki Yoong: Sort of. I was just finding it quite interesting, but not interesting as a series of works because there’s just something so kind of homogenous about them. Yet they encapsulated elements for us all to dialogue with, the portraiture element, the prominent presence of fabric and its materiality.

Florence Reekie Actually, when doing research, we found out Lely wouldn’t actually have had the subjects sit in those dresses. They would never have worn those dresses; they weren’t real; they’re just a concept. The portraits were totally curated from the beginning.

Maddalena Iodice: This curated element also taps into the notion of beauty as a curated construct itself. There is so much in society that tells us what beauty is or should be, so I think this show offers an important space for reflection on the hidden structures of representation. Starting from your own practice and the series you produced, I’d love to know what beauty means to you and how your relationship with it has morphed.

Leo Costelloe: It is constantly changing for me personally. I think about it more as a sort of spiritual notion, a feeling or a space of connection, more than something to be objectively appreciated. I wouldn’t say typical Beauty sits at the cornerstone of my practice. However, in alchemising codes and symbols, if the result happens to be aesthetically pleasing, then I guess that quality is what can facilitate people connecting to it. A lot of my practice is about working things out through touch and physicality. I play with a lot of feminine motifs, and I guess that cultural beauty is also intuitively associated with the feminine somehow.

Florence Reekie: It’s interesting that it is just assumed that they are quite feminine.

Leo Costelloe: Yeah, I mean, it’s also because I attempt to plug it in a way that explores my own personal identity but also leaves space for people to filter it through their own experiences.

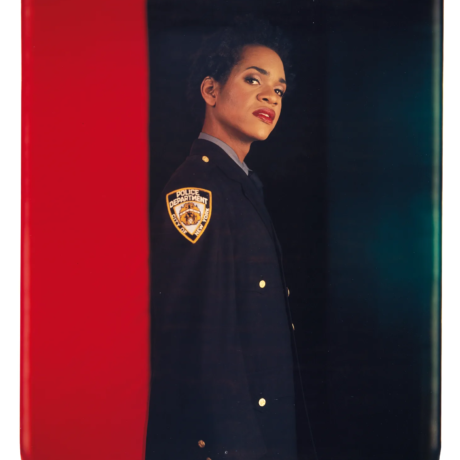

Florence Reekie: Leo described beauty in such a nice way… When I think about it, I can’t help but reflect on this idea of beauty being something you have to achieve and strive for and natural beauty being the pinnacle of that. The contradiction lies in the fact that the canon of natural beauty is often attempted to be achieved using very unnatural processes…

Ki Yoong: Beauty is definitely a word that I was thinking about when making work for this exhibition. The Windsor Beauties by Sir Peter Lely are called the “beauties”, which made me question what this word means and its meaning in the context of that specific art series. When looking at those paintings I kind of anchored the word to the term “English rose” as I think those portraits at the time were what epitomised English beauty in the sort of national sense of what “beautiful” meant. When painting, this set of reflections kind of guided me through the tension between what beauty looked like then and what it looks like now. What is today’s English rose? Is it something similar to the 17th century, or is it something very different? When it comes to people, I regard beauty as something that lies within. It might sound cheesy, but I always think about my mum because she’s such a gentle and kind woman. These are the qualities that I value the most, it is like a softness. That is what I associate with beauty and I try to put into the expression of my paintings.

Maddalena Iodice Inner values can totally change the outer perception we have of people. Which I think also links with the concept of storytelling and how it can influence our vision and, thus, our desires. Fashion plays as an example, where in the last eight years or so, as a reaction to the sexy and sexualised bodies of the 90s, charisma and personality became the new canon. Ultimately, that is what troubled the perfect-hetero-skinny-body image with body-positivity and more inclusive gender narratives. Leo, I’d love to talk more about the way your work delves into presupposed gender affiliations as you recast women’s beautification tools like ribbons or bows in incongruously hard materials such as glass and silver.

Leo Costelloe: A lot of the time, the motifs that I play with are means of subversion and exploration of overarching ideas or cultural ideologies. I start with something that’s perceived as very soft or fluid and make it out of something very hard or rigid. What is interesting about the bow as an object and a symbol is that it was born out of something that was historically functional and sort of utilitarian but then have undergone this transformation into a symbol of femininity or chastity, just like in the Windsor Beauties. However, I know that because of the way that my work travels, it is often re-contextualised and appreciated by people who are receptive to traditional ideas surrounding feminine beauty.

Florence Reekie: It is interesting how perspective on certain motifs can change based on what we assumed to be beautiful in the past and now. What stays the same, though, is the obsession with a certain aesthetic pleasure.

Leo Costelloe Yes, and even the conversation around beauty can switch completely. I mean, beauty is mainly understood as something very soft and gentle, as Ki said, but it can be profoundly aggressive, hard, angsty or spiky as well once you take the “gentile” conversation out of it.

Ki Yoong: Absolutely. That was why I wanted to make sure that I portrayed different types of faces, genders, ages and personalities. I wanted to expand the discourse, starting from what the notion of beauty was in Lely’s work.

Maddalena Iodice: How much of your life is articulated through your practices? Is your artistic discourse a reflection that starts from the inner world, from the observation of the environments you are exposed to, or something that sprouts from the materials you are working with?

Ki Yoong: Well, I’ve always loved painting and drawing ever since childhood. When I was young, I was really obsessed with Tudor paintings and paintings by Holbein, which, somehow, stuck in my head my whole life. I guess this explains why I’ve always just gravitated towards portraiture.

Maddalena Iodice: However, when I look at your paintings I do wonder if the subjects are people you know, or if there is any anecdote encapsulated in the scenes depicted by Florence or the jewels of Leo.

Florence Reekie: I think it’s all three things, isn’t it? I can’t really undo these three elements: materiality, the inner and outer observation. Maybe sometimes there’s much more of one than the others, but it is all entangled if that makes sense.

Leo Costelloe Making jewellery, there’s often a consideration of the body or a person at the end, but my process doesn’t really start from there. Things are certainly entangled, as Flo said, and depending on what I’m working on, I sort of focus on different areas. When I work with film, for example, it often feels purely observational, especially when you actually finish making the work and you have to edit and sit down with it. Sculpture, for me, often feels so purely material, especially when working with glass and metal. Something that punctuates all my practice, though, is a certain sense of intimacy.

Ki Yoong: Intimacy is such a fascinating space… my paintings are not specific portraits of people; I don’t intend them to be. Even though I might paint my friends, it’s not really important who they are because I kind of just want them to be a prompt for the viewer to sort of create their own narrative internally, create their own questions and ideas and reflect back on themselves. That’s kind of what I hope the works do.

Florence Reekie: That’s so interesting that you think ahead to people seeing your work. When I’m making, I don’t think about it as much, and sometimes I’ll be quite shocked by what someone gets from it because I haven’t really expanded enough to think about what someone else might see!

Maddalena Iodice: The tension between the impetus the work originates from and the viewer reading of it leads us to the next layer I’d love to delve into with you. To disrupt items’ presupposed gender affiliations, questioning the unattainability of cultural beauty standards or celebrating what makes each person uniquely alluring could be understood as a form of activism considering today’s socio-political temperature… Is there such an intention behind the work? Where do you situate your practice within contemporary cultural discourse? I think artists often find their work inappropriately labelled, which is something that happens a lot with women and feminism, for example.

Leo Costelloe: Similarly, there was and probably still is a very intense moment where people position queer identities and their work within a discourse where they automatically become this political beacon for queer art across the world.

Florence Reekie: They make the work only about that.

Leo Costelloe: I think it can be very limiting or constraining to link individual identities so strongly to artworks. I can’t speak for everyone, but for me personally, I don’t necessarily enjoy my work to be confined to this discourse. There’s a huge push on gender identity in regards to making or producing, and that’s happening across all art disciplines. It is important, but I think as a main means of consuming work, it shouldn’t necessarily be the primary focus.

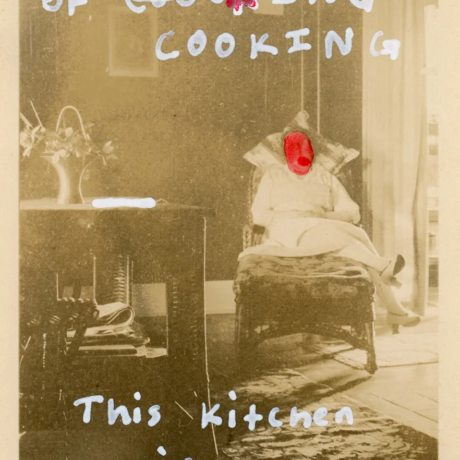

Florence Reekie To engage with awareness is crucial, I think. And it has been very important for me as I worked on this show. The painting A Natural Smooth Look Too, for example, kind of questions and looks into those things we assume as normal…on the packet of the nipple covers, the title was “It’s a natural smooth look”. Stickers to make you smooth it’s not natural, which really unlocked a reflection on things we unconsciously internalised as the norm. It played as a reminder for me to grow a bit more awareness.

Ki Yoong When I am making work, I consider the importance of portraying a diverse range of subjectivities, but then I just really focus on the person. Each painting is a celebration of a particular type of face, a particular feeling. I can’t describe the multitude of human experiences, what I do is more like a microcosm, isn’t it? It’s a moment.

Leo Costelloe: Sometimes, there is a weird pressure people put on artists… If we were talking about advertising or fashion, there would be clauses and certain quotas to be filled. However, as an artist, it’s not necessarily your job to speak on behalf of multitudes of people; it is a position that liberates you from those dynamics. I vaguely worked in fashion and you do get very bizarre readings of things because you are, for the most part, trying to sell things to large groups of people..

Maddalena Iodice Everything changes when marketing and sales come in. As you grow through your career, how do you deal with the commercialisation of your work? The tension between the instinctive nature of your practice and the awareness of what would actually sell?

Florence Reekie: When I get commissions, I find it really stressful. It’s a whole different process, and people’s expectations are very different as well.

Ki Yoong: Yeah, I just try not to do commissions. There’s a big difference between being presented with someone’s face and being requested to paint it or just me doing that instinctively and selecting someone. With commissions, the commodification of the artwork comes into the process, which automatically just makes it less enjoyable for me.

Florence Reekie: It’s hard, though, because it’s not always possible to say no to things like that…Also, It’s interesting how Windsor Beauties had very little to do with how those women actually looked. It was just a status thing. Someone trying to sort of give an idea of what they are is very different to when you’re making something that is your version of it.

Leo Costelloe For me, this is a large part of why I have gone down a jewellery route, a liminal space between art and jewellery, to support my practice financially.

Maddalena Iodice Which is a choice I understand, and yet enhances the logic of an industry where emerging and early-career artists struggle in building a sustainable career path. Thank you all for this generous conversation.

Writen by Maddalena Iodice

*The Windsor Beauties “Windsor Beauties” is the name given to the collection of eleven portraits painted by Sir Peter Lely (1618-80) of celebrated courtesans and women of the nobility in Restoration England. Commissioned by Anne Hyde, Duchess of York in an attempt to consolidate her power, the series features depictions of mistresses to the King and his confidants, Anne and the women closest to her – each intended as an alluring vision of perfection.