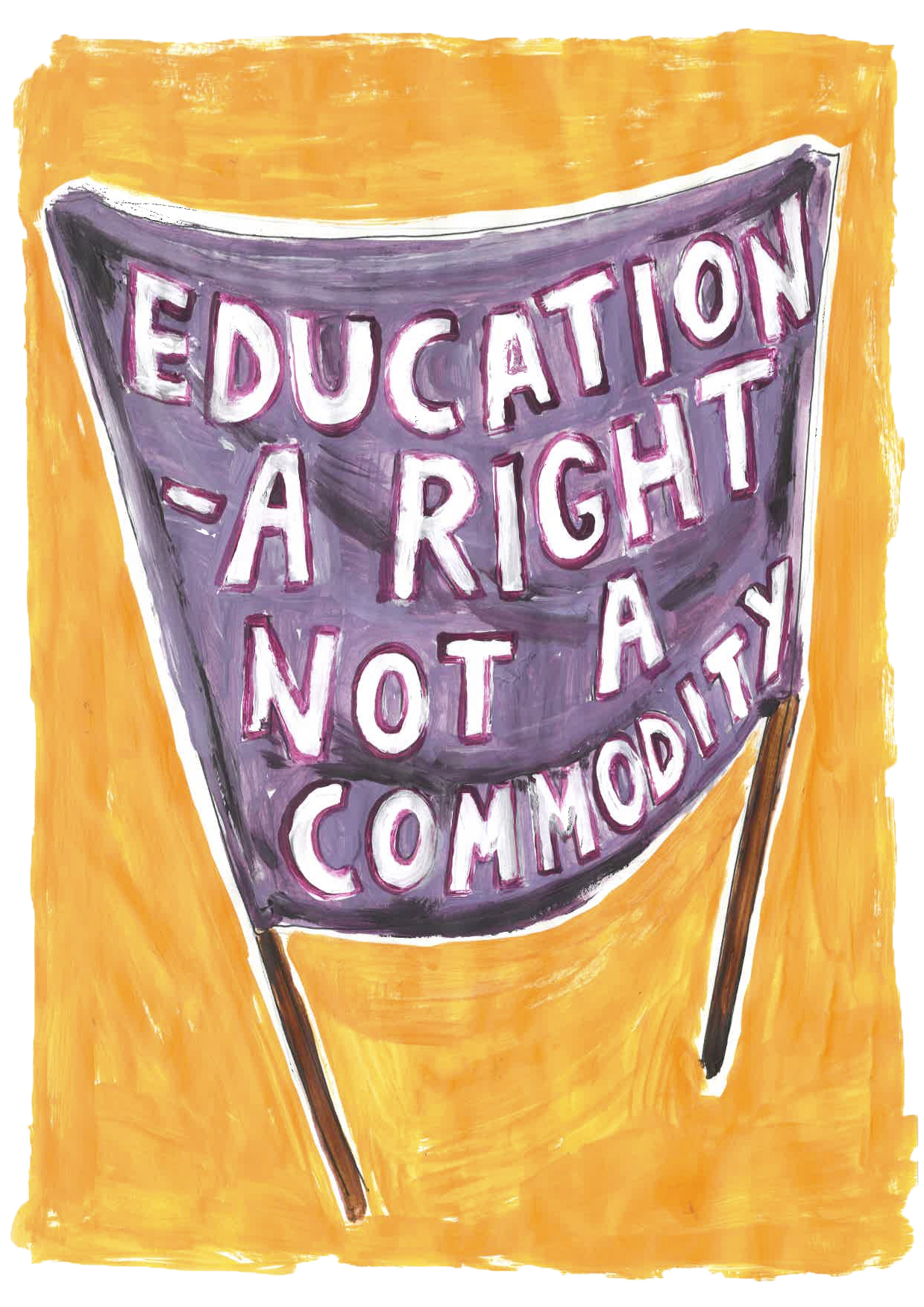

What happens when a university strikes? Which services are hit and who is made to bear the consequences of mass walkouts from classrooms, lecture halls, studios and “sites of educational activity”? As many staff members at sixty-one UK universities are in the fourth week of a period of strikes which began in late-February over substantial changes in pensions—some of the biggest industrial action seen in recent times—questions about the role of universities, their courses and the role of staff have once again been thrown up for discussion. Complex, ongoing shifts and developments in education are offered out piecemeal to public debate by a variety of experts, impassioned commentators and those just willing to throw their hat-cum-opinion into the ring and get involved. Some commentary comes from a desire to generate nuanced conversation, while some seems to be more of a polarizing, reductive “taking a stance” opinion. In this swirl of ideas, nowhere else are these feelings of “What’s it all about?” brought into sharper focus than when thinking about the shape and career of education dedicated to culture, arts and the humanities.

What happens when a university strikes? Which services are hit and who is made to bear the consequences of mass walkouts from classrooms, lecture halls, studios and “sites of educational activity”? As many staff members at sixty-one UK universities are in the fourth week of a period of strikes which began in late-February over substantial changes in pensions—some of the biggest industrial action seen in recent times—questions about the role of universities, their courses and the role of staff have once again been thrown up for discussion. Complex, ongoing shifts and developments in education are offered out piecemeal to public debate by a variety of experts, impassioned commentators and those just willing to throw their hat-cum-opinion into the ring and get involved. Some commentary comes from a desire to generate nuanced conversation, while some seems to be more of a polarizing, reductive “taking a stance” opinion. In this swirl of ideas, nowhere else are these feelings of “What’s it all about?” brought into sharper focus than when thinking about the shape and career of education dedicated to culture, arts and the humanities.

My relationship to education has wound a sometimes directionless path. GCSEs and A-levels provided me access to an art foundation course at (the now closed) Maidstone UCA. A degree in painting followed, and after graduating from Brighton University in 2012 I spent some time managing a street food business before moving to Brussels to work for an arts organization, overseeing and organizing, amongst many other tasks, a touring sculpture exhibition. I maintained an art practice throughout these years, participating in exhibitions, residencies and art fairs. As the projects I had been managing in Brussels neared their end, I decided to apply for a masters in London. Keeping both career-enhancing prospects and mind-expanding ambitions in mind I applied for, and was offered a place on, the MA in cultural studies at Goldsmiths.

“Attention should also be paid to different pathways, residencies, alternative MAs, short courses and learned-on-the-job professional experience”

Arts education (in the UK at least) is an ever-expanding field and has changed drastically from its links with locally-based colleges, once common around much of the UK. In the years that have passed, courses and departments have gradually been upgraded to university status or merged with existing structures. Once perceived “soft” options have been rendered equivalent with courses in diverse areas of research, and practical skills having now “risen” to the ranks of degree, masters and PhD. Unique disciplines so long the sacred experience of a few have been developed and remoulded to sit alongside other university courses. But as workspaces change and student numbers increase, the voices of praise and satisfaction, once proud to witness their subject areas made equivalent, are transformed into shouts of frustration and anger as they find their environments in a state of continuous change.

So, what does a university strike look like, especially for anyone engaged in new and traditional arts education? When staff members walk out for an extended period of strikes, do the students suffer? Lectures have been missed, but what about the reading lists which may already be published online? Or how about the students on placement, away from campus for three months working an internship as a required, graded part of their course? Studio doors have remained open (at least at Goldsmiths) so what then will cultural producers-in-waiting miss out on?

Following this line of thought, it may be perfectly reasonable to argue that a place on a course and the fees paid are little more than access to reading lists, facilities or equipment. Who needs tutors when summaries of many different lines of thought exist for free online, or when feedback about work is provided by a double-tap love heart from followers on social media?

“At worst, reluctant academics guide students through a series of professionalism courses, meeting the prescribed targets with little or no idea of life outside of academia”

At best, universities offer the chance for the breaking down and rebuilding of ideas and practices; they operate as an antidote to quick-fix bitesize understandings of complex ideas; in a flexible, reactive, but well-supported environment, tutors illuminate, draw out of and challenge students to move further, tread dangerously into territory yet unknown, setting in place a fracturing of world-views; transformation from the outside in. At worst, reluctant academics guide students through a series of professionalism courses, meeting the prescribed targets with little or no idea of life outside of academia; their own personal history a series of institutionally re-enforcing career moves.

As the conditions for tutors falls, worryingly sliding to match those from which the majority of students rise from and enter back into, that of raising precarity and sustained portfolio careers, it could be argued that new possibilities for unison between staff and students is opened up. If what is provided by arts education in its myriad forms demands nuanced conversation, we should listen to those who speak from within. Attention should also be paid to different pathways, residencies, alternative MAs, short courses and learned-on-the-job professional experience. It’s time to tell the alternative stories. Time to focus, not on the blazing stars of the art world but on those who, instead of fame and fortune, tread a path of compromise, of trying to imbue every day with creativity, a life lived in the spirit of their formative education.