It’s the first Monday of February, and art week has kicked off in Mexico City. Inside Lodos, in the central Juárez neighbourhood, a procession of spectators of all ages lean over to carefully examine a sequence of bronze sculptures and peephole boxes mounted to the walls. Each of them holds tiny vignettes with drawings and fragments of text that illustrate each chapter of George Bataille’s Le Mort. Raised eyebrows and chuckles inundate the pristine white room as the onlookers uncover the wicked nature of the French author’s story: A woman mourns the death of her lover in her arms; she enters a bar barely covering her naked body in drunken stupor she mingles with characters that initiate a series of sexual acts charged with body fluids including piss, shit and puke, and which culminate in the death at dawn of the main character. “El Muerto” exhibits the work of Newton, the pseudonym of a seventy-six-year-young Mexican artist, who, similarly to Bataille, chooses anonymity to delve into these dark matters. But to most in the room, the author of these works is no stranger. Newton has developed a cult-like following among younger generations in the past years, and with her thick black-rimmed glasses, she is easy to point out in a crowd.

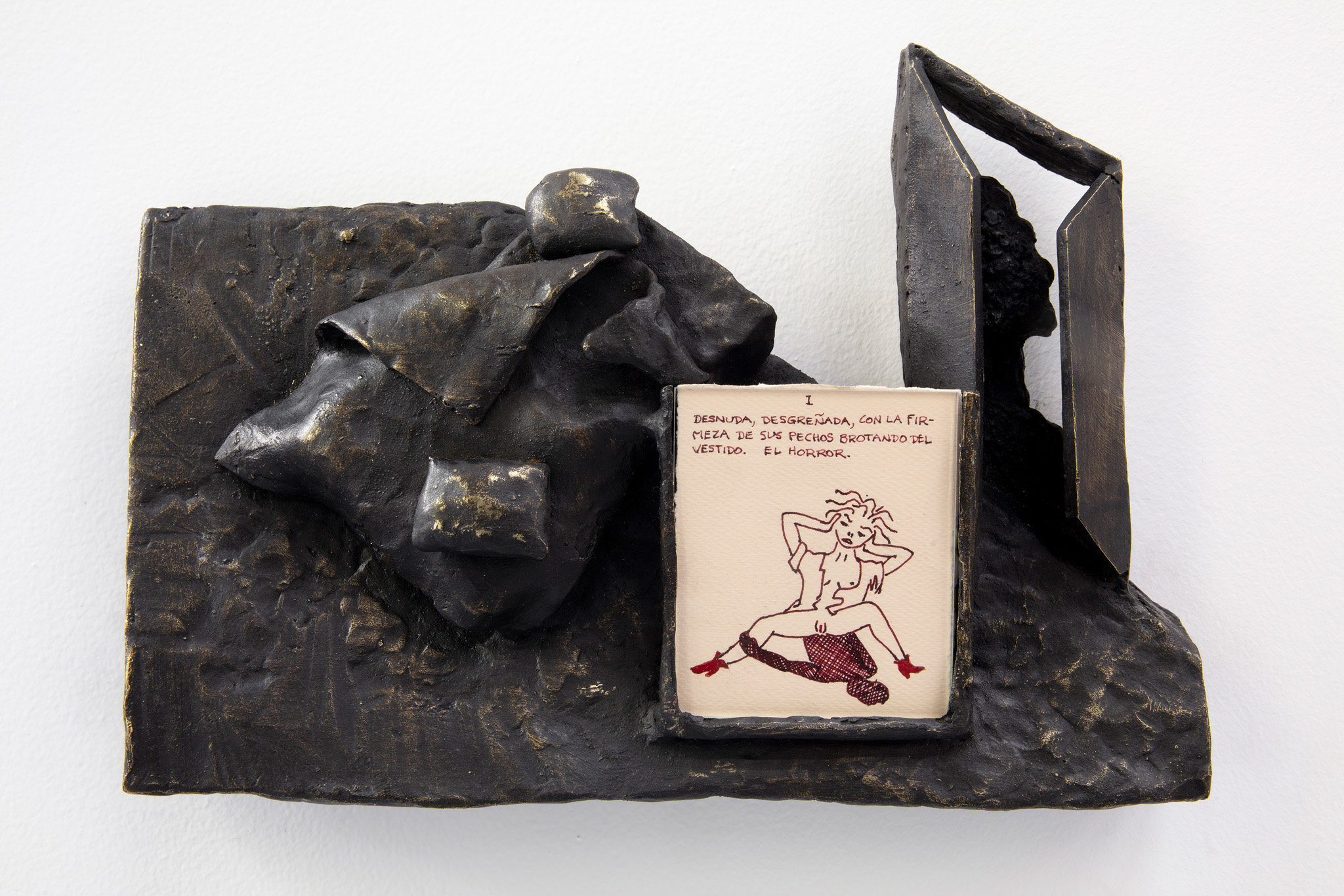

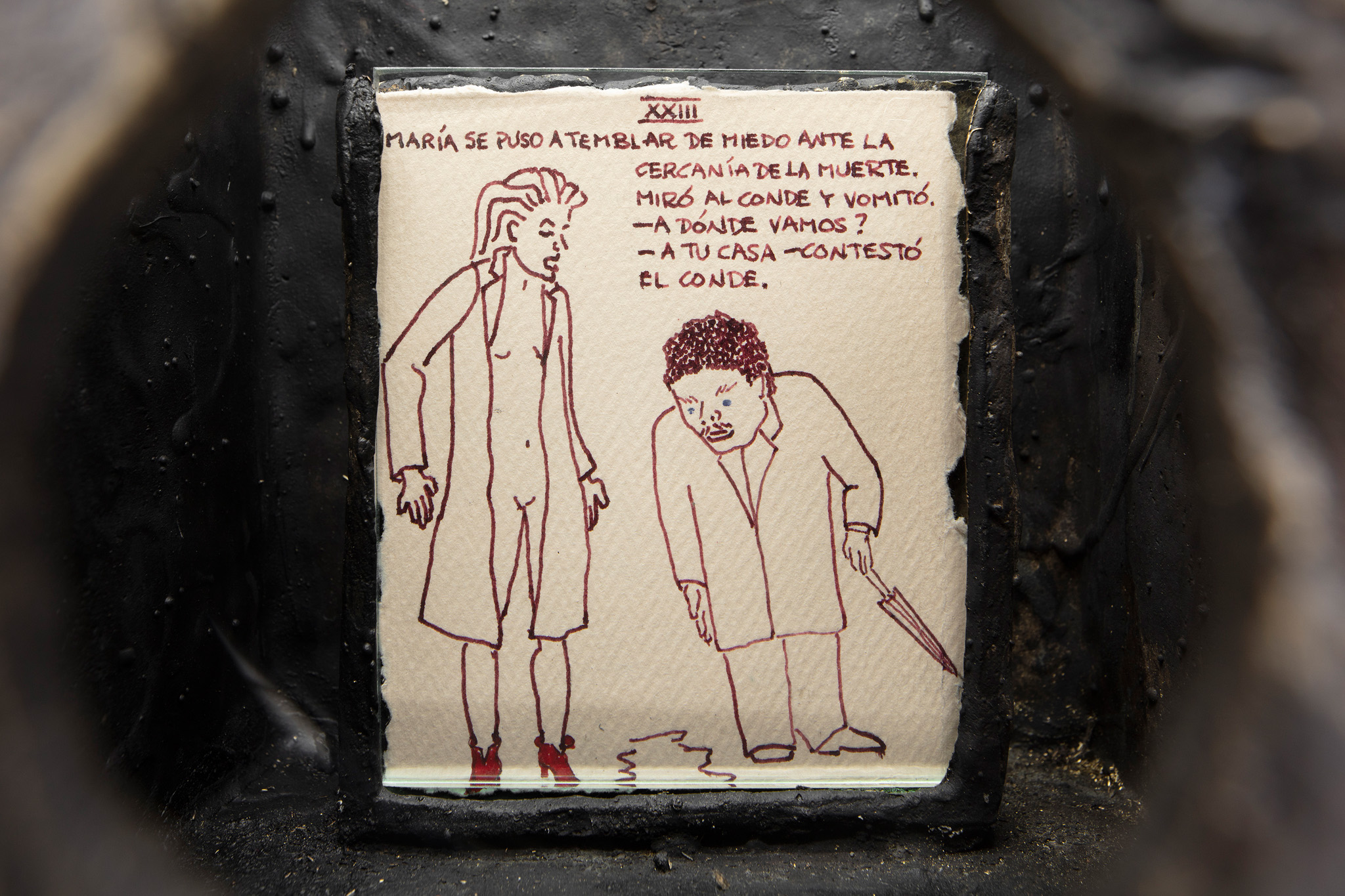

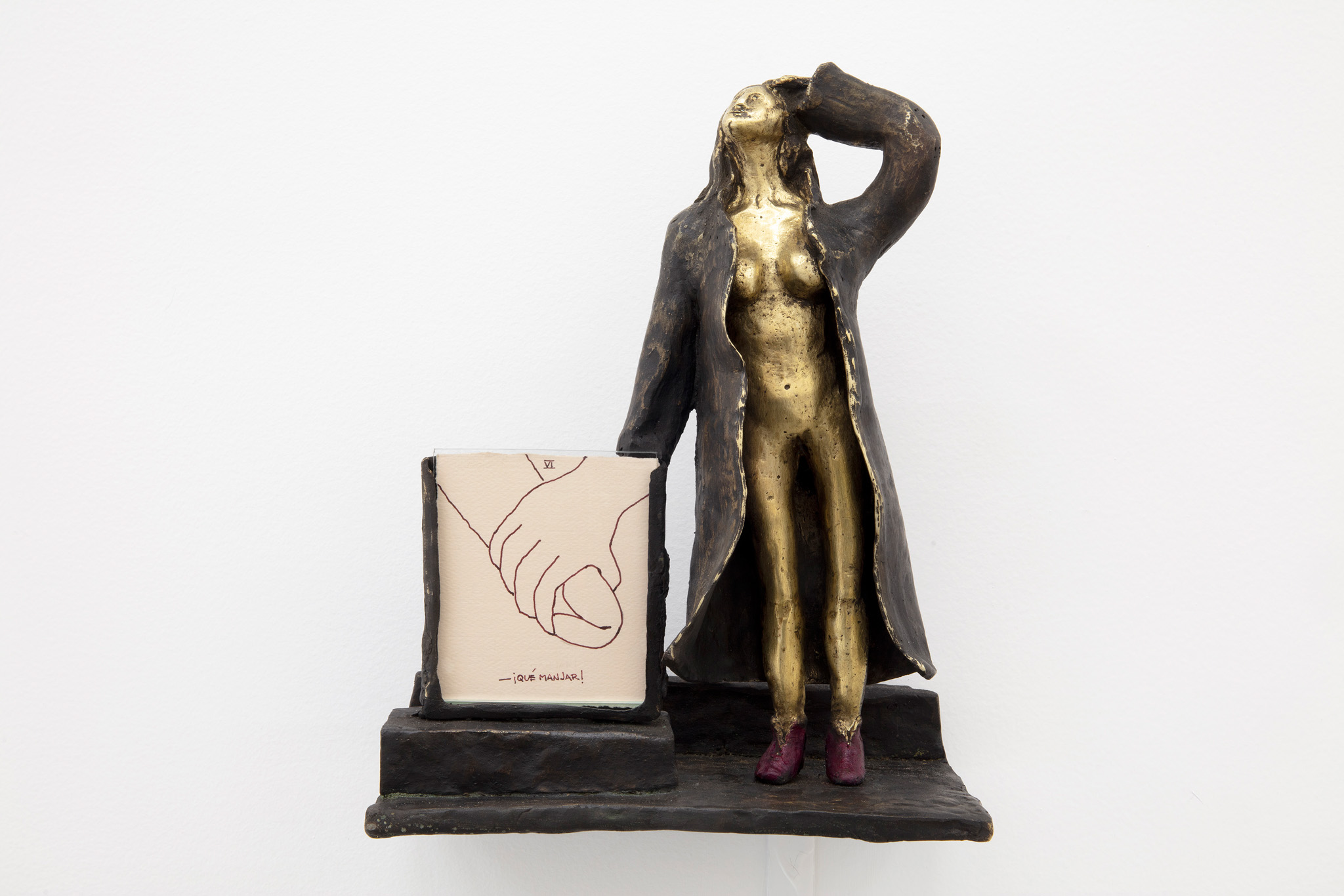

The drawings are merged with the sculptural frames that support them; in them, the lines of the twenty-eight drawings etched with two hues of red ink pens are reduced to a minimum necessary to convey tiny genitalia and hysterical reactions of a horny midget, the demanding bar patron and an unsatisfied count. Half of the works in the exhibition have a sculptural approach to the bronze casts, with ranges of polished metal shining through a black tar patina and red pigment applications. El Muerto XI & XIII are bas-reliefs of open buttocks being pleasured by a face profile and a face-fronting reaper holding a scythe. Others take full three-dimensional forms. El Muerto VI assumes the form of the mourning woman wearing nothing beneath a coat, and El Muerto XII shows a woman hanging dead from a tree. El Muerto III & IX display oceans and forests, which are formally closer to Newton’s past sculptural work with bronze, where she portrayed landscapes of memories, dreams, and songs in similarly-sized rectangular casts. It is in the background textures where one can sense most the hand of the author, where organic grooves evidence the clay and wax carvings that preceded the pouring of the hot liquid alloy.

Newton’s obsession with Bataille spans back several decades. In 1978, her then-boyfriend, Mexican multidisciplinary artist Juan José Gurrola, gifted her the manuscript of Raúl Falcó’s translation of Le Mort. She handwrote it word by word as a way to absorb and manifest through her body the erotic lessons learned. As part of this exhibition, Falco’s translation is being published for the first time in a booklet where Newton’s drawings are veiled in-between folded pages of text and can only be fully accessed when the reader cuts a permanent slit on the sheets. Shortly after meeting Gurrola, Newton would conceive her only daughter, Edwarda, named after another of Bataille’s guilt-free pleasure-seeking female characters.

Visiting gallerist friends from Los Angeles wondered why an artist with so many years of work behind her hadn’t had more public recognition. “Was it because she was busy being a mother?” they asked. To a certain extent, but a young Edwarda would soon develop a strong agency as a Mexican TV child star. The biggest impact in Newton’s life would be the enormous artistic (and an equally big physical) presence of her husband. Together for three decades until his passing in 2007, she would partner with Gurrola as his wife, muse and archive custodian. First approaching sculpture in 1981 when she joined a woodcarving workshop, she would explore endlessly with this material her favourite subject: the phallus, occasionally encasing the monoliths in wired metal cages. The affinity for box-like structures can be explained by the workstation Newton gives herself to develop her sculptural work, a desk where everything is within hands-reach to get into the most meticulous details. Sculpture has always been Newton’s private medium, off-limits for Gurrola, who had plenty other disciplines to explore.

An overall theme of desire encompasses all of Newton’s works. But not only to the sexual act in itself, but to the fantasies and perversions that engulf the mind when one yearns for it. As Mauricio Marcín cites an anonymous author in the exhibition text, “The important thing about eroticism is to desire; everything else is sex, pure gymnastics”. Bataille was obsessed with this sort of desire, an impulse so pure that it could provide an ecstasy only similar to death, la petite mort. He meditated on the inevitability of erotic lust stemming from the transgression of admitted moral sexual behaviours that are ever more delicious to surpass, an intoxicating sinful pleasure that can only lead to the maximum punishment: death. Erotic desire reminds us of the true chaotic nature of all around us. Beyond human rationalizations, categorizations and interpretations of the world there’s the consciousness of our own mortality, of death and violence.

Authored under the name of Lord Auch, Bataille’s Story of the Eye follows a teenage couple’s exploration of increasingly depraved sexual acts, attracting an ensemble of deviants that spiral down to their fatal endings. Simone, the harbinger of the original sin in this story, has a knack for inserting round-shaped objects in her cavities, among them the eyeball of a priest. The act of looking is central to the other fourteen works showcased at Lodos; a peephole in the bronze and glass boxes lures the spectator to lean in to view the drawing and text vignette contained. It is inevitable to be reminded of Marcel Duchamp’s last work, Étant donnés, where through a hole in a wooden door, one finds an installation of a headless body of a woman lying on a grass foliage with her legs wide open to the viewer.

But this is not the first time Newton has spectators bending down to have a closer look at her work. It was 2020 in Mexico City, in the midst of the burgeoning independent art fair markets and just before we had the full force of the international interest that came after the pandemic, when after a pause after Gurrola’s death, Newton resumed her practice by showing new work in the backdoor of the artistic scene. At Casa Gomorra, a queer commune in the working-class neighbourhood of Obrera, for a span of thirty minutes or so, Spanish performer Maria Perkances opened La Retaguardia del Arte, a gallery located inside her anus. Lying down on a table and with the help of a speculum to keep the cavity open, one could certify through a magnifying lens the presence of a tiny DNA coil figurine amid the cavernous walls.

At that time, the repercussions of the #MeToo movement had stiffened mainstream sexual dynamics, leaving little room for risky practices and favoring a total transparency of agreements preceding any sexual act. A total annihilation of erotic desire as understood by Bataille, where the pleasure resides in the unpredictable dangerous nature of the act of consummation. Answering the question of Newton’s newfound visibility posed by the temporary foreign visitors, it might be that her artistry (and her non-conforming approach to subjects such as love and ageing) was just too transgressive for the past times. Throughout coming and passing waves of cultural sexual repression and disinhibition, and while the art world fixated on artists dedicating their whole lives to a single medium, Newton found new allies in young theater kids and BDSM subculture enthusiasts. A total work of art, her material practice is deeply rooted in a philosophy for living life without limiting one’s impulses.

Back to the present night, the artist and the congregation gathered at Lodos have moved on to La Dominica, a bar deep in downtown favoured for its lax indoor-smoking rules. Around two hours before midnight, the lights are dimmed, and a toxic cloud of smoke floods the room, causing onlookers to squint their eyes in tears and cough frantically. From it emerges legendary actress Arianne Pellicer, embodying the female lead of El Muerto. In a staging directed by Pepx Romero, curator of the exhibition, Pellicer walks down the bar counter, reclines in a wood-carved seat and engages in the acts described by the French author. The drunken crowd cheers ecstatically when they hear the perverse narrations by Romero and the raptured moans by the performer. The party goes on until the late hours, much like many after-parties in the artist’s private residence filled with overflowing booze, chain-smoking and hedonistic affairs. At her age, Newton is conscious of the impermanence of the flesh. But when her earthly immanence ceases to exist, her legacy will remain in her devotees, who understand that when you’re not afraid of death, you’re free to live.

Written by Fabiola Talavera