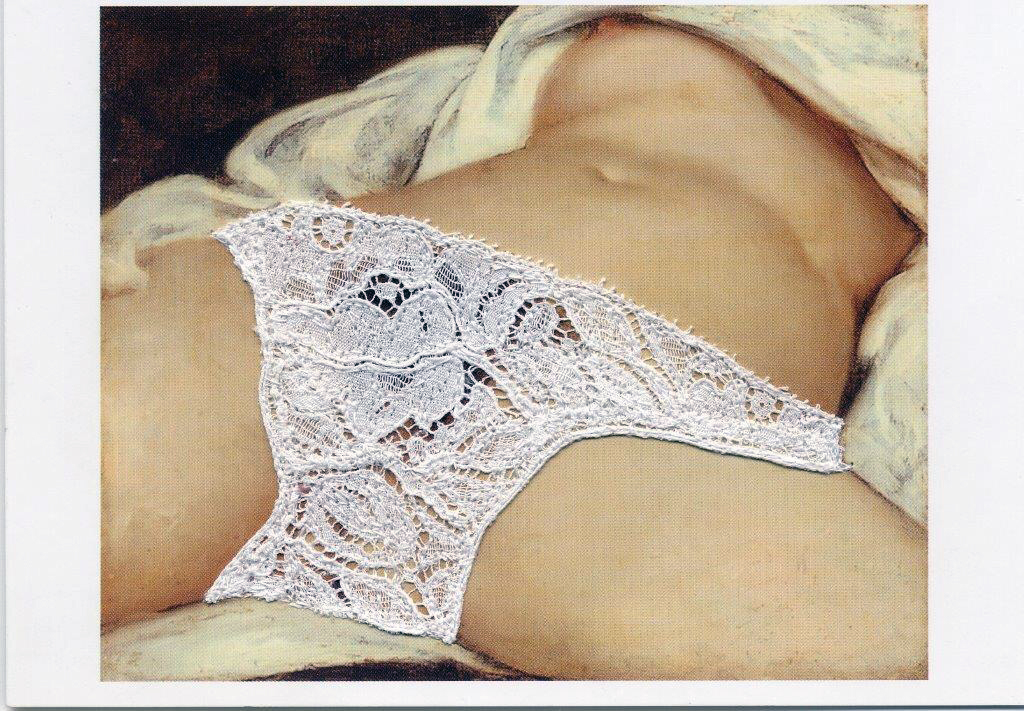

In 1866, Gustave Courbet completed L’Origine du monde, an oil painting of a woman’s vulva, breasts, and abdomen. Though Courbet earned himself a legacy as one of Realism’s founding fathers, the painting was not exhibited during his lifetime and remained hidden until the twentieth century. Acquiring it in 1955, French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s reputation as a prolific art collector helped the artwork ascend to infamy. Only then did L’Origine become as polarising and daring as we know it today.

Courbet’s painting signified a radical shift in traditional depictions of the female body in art. He was deeply critical of the duplicitous social norms of the Second Empire, where erotic, explicit, and pornographic imagery was deemed acceptable only when they were situated within mythological or religious contexts. As a result, Courbet, alongside Manet, distanced himself from the artistic conventions of the time, committed to capturing a stark but brutally honest depiction of female genitalia.

In the 157 years since L’Origine’s creation, today’s responses to vulva-centric art feel similarly hostile. Consider the backlash that Brazilian artist Juliana Notari received in 2021 after the unveiling of Diva, a 33-metre reinforced concrete vulva, on the grounds of a former sugar mill in Pernambuco. Notari claimed that the piece is a response to the increasingly intolerant socio-political climate fostered by former President Jair Bolsonaro, questioning ‘the relationship between nature and culture in our phallocentric and anthropocentric western society’. Diva, unsurprisingly, sparked mass outrage from Bolsonaro’s Far Right supporters – proving Notari’s point exactly.

At first inspection, it’s easy to mistake vulva art as gratuitous for the sake of generating deliberate outrage. What, after all, is a better way to get people talking about your work than engendering controversy? But Courbet, Notari, and the works of countless other artists dig much deeper than that. The phallus has remained a dominant fixture in art throughout history – think of Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504) and Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (1490), to name the most recognisable works. The vulva, however, remains ever taboo, ever explicit, ever the subject of censorship.

While this dichotomy – vulva: bad, penis: good – can be unassumingly explained away by patriarchal thought, its sundry manifestation across cultures speaks to a broader intersection of oppression. In my own work – researching reproductive healthcare in literature and film – I’m often compelled to consider the place of sex and sexual anatomy in creative works and what pedagogical power these portrayals may hold. Vulva art is certainly no exception – and nor is the cultural response that these pieces illicit.

Since the 1950s, the work of Puerto Rican artist Zilia Sánchez has blatantly invoked the female form through anthropomorphic protrusions. Her sculptures capture the sensuality and organic forms associated with femininity, combining elements of abstraction and eroticism; her paintings, characterised by their remarkable spatial qualities, emit a distinctly minimalist sensibility while also challenging and subverting that very idea.

Today, Sánchez’s legacy is one of ’a cartographer of intimacy’, but it was only at age 93 that the artist had her first retrospective, Soy Isla, in 2019 at the Phillips Collection. Vesela Sretenović, a curator at the Collection, suggest that her work wasn’t subject to the same censorship that other erotic artists were in the 60s and 70s. ‘She was living in New York City as an outsider [then], showing in small Latin American art galleries, she wasn’t part of the mainstream,’ said Sretenović. ‘She is a woman, she is Latino, and she is gay. So, not the most popular combination in the world.’ Had she been anyone else, Sánchez’s career may not have endured for as long as it did.

Vulva disavowal isn’t just a problem in the art world, though. In 2010, the film Blue Valentine originally received a rare NC-17 rating in the United States for the inclusion of a single scene of oral sex, even without a vulva in frame. Its star, Ryan Gosling, suggested that the scene’s authenticity was the source of controversy: ‘It was really important to us that it made you feel like you were watching people have sex,’ he said, ‘not like you’re watching a sex scene’. For the Motion Picture Association, the mere insinuation of cunnilingus was too graphic to be included in an R-rated film. Preceding that, an oral sex scene in Basic Instinct (1992) was cut so the film could get an R rating, a decision later underwritten by the inclusion of Sharon Stone’s infamous ‘vagina-shot’. The scene sparked a global debate about representation, empowerment, and objectification, and Stone was thrust into stardom as an international sex symbol. On that scene, Stone penned a 2021 Vanity Fair article, claiming that outrage was very much a product of misogyny: ‘This was 1992,’ she wrote, ‘not now when we see erect penises on Netflix’.

The vulva, for Stone, was something she had not originally intended to display to the world. The same cannot be said for the work of performance artist Carolee Schneeman made, who similarly made headlines when she unapologetically drew a roll of paper from her vagina, upon which she had written a female critic’s criticism of her work. Schneeman acts as a major inspiration for Lauren Elkin’s recent book Art Monsters, her art contextualised through the legalisation of the birth control pill and abortion in the United States.

In a similar vein, Casey Jenkins’s performance piece Casting off My Womb also attracted international outrage. For this piece, Jenkins spent 28 days knitting from a ball of yarn lodged in her vagina to symbolise a full menstrual cycle. Originally intended to be a ‘meditative, slow, and rhythmic’ reflection on societal pressures, Casting was swiftly overshadowed by a wave of sensationalism – the piece branded ‘repugnant’, ‘thoughtless’, and ‘unclean’. Jenkins, like Schneeman, was not deterred by her detractors. Her 2016 follow-up Programmed to Reproduce saw her use vagina-spun yarn, hacked knitting machines, and an interactive ‘mental endurance’ exercise to confront her harshest critics head-on.

Here’s what I find the most compelling about the legacy of the vulva in art – the idea of how it manifests itself as both a site of power and corruption but also of weakness and fragility at once. Psychoanalysis à la Lacan and Sigmund Freud tenders penis envy as an explanation for the inherent contradictions of the vulva. Etymology offers us another. Dating back to the seventeenth century, vagina – here interchangeable with ‘cunt’, often misattributed as a vulva – was introduced as a medical term, literally translating ’a scabbard’ or something to put one’s sword in. It makes sense that, historically speaking, the sword – an emblem of dominance, size, and power – is interchanged here with a penis when men have long dominated the medical profession. As Hannah Williams incisively writes for Granta, ‘The female body is defined by its fundamental lack: uncanny, strange, and unfinished. It’s why so many euphemisms for the vagina focus on the female genitals as a wound: cleft, axe-wound, gash – the woman is always a site of violence.

Although this is reminiscent of more recent vulva discourse, the global proliferation of vagina dentata myths has long positioned female genitalia as deadly and dangerous. The term – in a shock to no one – was coined by Freud in 1899, but stories of vaginas with teeth long had already been around for millennia. In the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, one of the most popular folklore tales features a Brahmin who is convinced his love interest has a vagina dentata. In Japan, a Shinto tale recounts how a demon hid teeth in a damsel’s vagina. The list goes on.

Just as the idiom to ‘bare one’s teeth’ has long been thought of as synonymous with aggression, the baring of one’s genitalia is much the same. But the vulva, in all its vulgarity and splendour, is also undergoing a profound recontextualisation across both word and image. Once described by lexicographer Francis Grose as ’a nasty word for a nasty thing’, cunt was elsewhere misguidedly deemed ‘the most heavily tabooed word of all English words’ by Hugh Rawson. A word used unblushingly by Geoffrey Chaucer throughout The Canterbury Tales (1392), cunt has also been effusively reclaimed as part of the queer vernacular, particularly where Black trans communities are concerned. One speaker in Eve Ensler’s 1996 play, The Vagina Monologues, likewise declares that she has ‘reclaimed’ the word. ‘Dick’ and ‘cock’, meanwhile, remain crude if juvenile insults but otherwise widely accepted – much like the penis’ recurrence throughout art history.

Beyond its codification as a symbol of queer empowerment, the vulva’s recent reclamation in art is inextricable from discourses of sexual violence, misogyny, trauma, and how we can. Make the move beyond it. In 2011, Jamie McCartney completed his groundbreaking sculptural project, The Great Wall of Vagina, which features a diverse array of plaster casts of women’s vulvas. This, he claimed, was a response to the rising number of vaginal cosmetic procedures and ‘body fascism’. ‘I do believe that cosmetic surgery is a fairly unnecessary procedure; it’s a psychological problem,’ McCartney said. ‘There’s a whole industry base set up to persuade women they’re defective and to give them an answer.’

McCartney’s Wall echoes the celebratory reverence of Judy Chicago’s 1979 groundbreaking sculpture The Dinner Party. Sparking outrage after its initial exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the piece comprised a three-winged table with thirty-nine place settings for notable women in history, each wing a nod to the Last Supper attendees. The first wing covers prehistory, the development of Judaism, early Greek societies, and the Roman Empire; the second focuses on women from early Christianity to the Reformation; the third highlights prominent figures from the American Revolution to the Women’s Revolution, spanning Anne Hutchinson to Georgia O’Keeffe.

At each setting, china plates feature motifs resembling butterflies and vulvas. The artist’s objective here was two-fold. Firstly, she wanted to highlight that the common thread uniting these often-overlooked women from history was their shared anatomy, transforming the vulva’s significance into a symbol of heroism. Secondly, she sought to reclaim and celebrate the vagina. For centuries, the vagina had been wielded by men to establish a sense of ‘otherness’ and demean women, seldom portrayed in any context beyond pornography. As Chicago explains in her memoir, Through the Flower: ‘I wanted to express what it was like to be organised around a central core, my vagina, that which made me a woman’.

A far cry from Chicago and McCartney’s joie de vivre, the interdisciplinary art of Doreen Garner works to expose the abuse historically inflicted on the female body. Explicitly the Black female body, in this case. Although Dr J. Marion Sims has oft-been revered as the father of modern gynaecology throughout my research, it’s an affectation I’ve since learned obscures a legacy built upon the experimentation, degradation, and torture of Black women. Throughout her body of work, Garner depicts Sims’ barbaric practices, deconstructing his image and even going as far as invoking the ghosts of three of his victims – Anarcha Westcott, Betsey Harris, and Lucy Zimmerman – in her 2019 show, She is Risen.

The results are inevitably disturbing; in Olympia, Garner sits images of ghostly pelvises on a wooden shelf, splayed open to reveal a void within, the vaginal slit starkly visible. The legs are absent, the interior is a vivid mixture of red and yellow silicone viscera. Nearby, artificial flowers with brown, hairy stems unfurl to reveal pink calla-lily-like blossoms surrounded by metal pins. Betsey’s Flag (2019) reimagines the American Flag: material adorned with silicone, latex, Swarovski crystals, hair, and the formation of human organs on one side, slashed foam with star-shaped incisions on the other. It’s in these pieces that Garner skilfully subverts’ the surgeon as artist’ corollary of Richard Selzer’s 1996 essay ‘The Knife’. In the words of Jareh Das for X-Tra, Garner’ actively liberat[es] the pained bodies of Black women by addressing trauma that has been overlooked in ‘fleshy recollections of traumatic histories’.

While Garner’s vulvas may often undergo deconstruction or abstraction, her work relentlessly encodes broader racial and gendered politics. And if the sexual and reproductive liberation of the 1970s looms large over the works of Sánchez, Schneeman and Chicago, then it’s only befitting that the ongoing threats to reproductive autonomy are central to Natari, Garner and Jenkins’ creative practice.

Eileen Myles, who recently faced censorship over their inclusion of the word cunt in a poem to be published in an anthology, poignantly that: ‘It means so much for the word ‘cunt’ to be reclaimed and talked about when, in places like the US, the politics of the right is really taking over when it comes to women’s bodies.’ Much the same can be said about the necessity of the vulva in art. Between the 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade in the United States and the recent Orwellian surveillance of menstrual tracking apps in the United Kingdom, owning a vulva feels like a grim prospect right now. And that’s overlooking the pervasiveness of sexual violence, medical negligence, or even body shaming we may face.

In a world where the vulva has long been marginalised, misunderstood, and subjected to censorship, the artists who unapologetically explore these subjects help to play a crucial role in reshaping our perspectives and dismantling the entrenched taboos. By delving into the multifarious legacy of the vulva emblem, art might pave the way for a more inclusive and liberated discourse on gender, sexuality, and bodily autonomy. But whether the vulva will ever lose its shock value has yet to be seen.

Words by Katie Tobin