Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death at Istituto Santa Maria della Pietà is a collection of startlingly beautiful images from two different prominent series. Twenty-nine of the images are portraits from the New York queer scene, a project started in the late 60s that continued until the artist’s death; the other 11 are of swaddled, mummified corpses and their surroundings, photographed in the catacombs beneath a cathedral in Palermo.

The photographs, all gelatin silver prints, comprise the entirety of his 1976 book of the same name. The book itself is legendary, not least for the fact that it was the only book of his work that he personally oversaw before his death from AIDS-related complications in 1987. The story goes that Hujar, meticulous and detail-obsessed, was never happy with the print quality. However, the prints on display are assured, immaculate, precise, and utterly compelling.

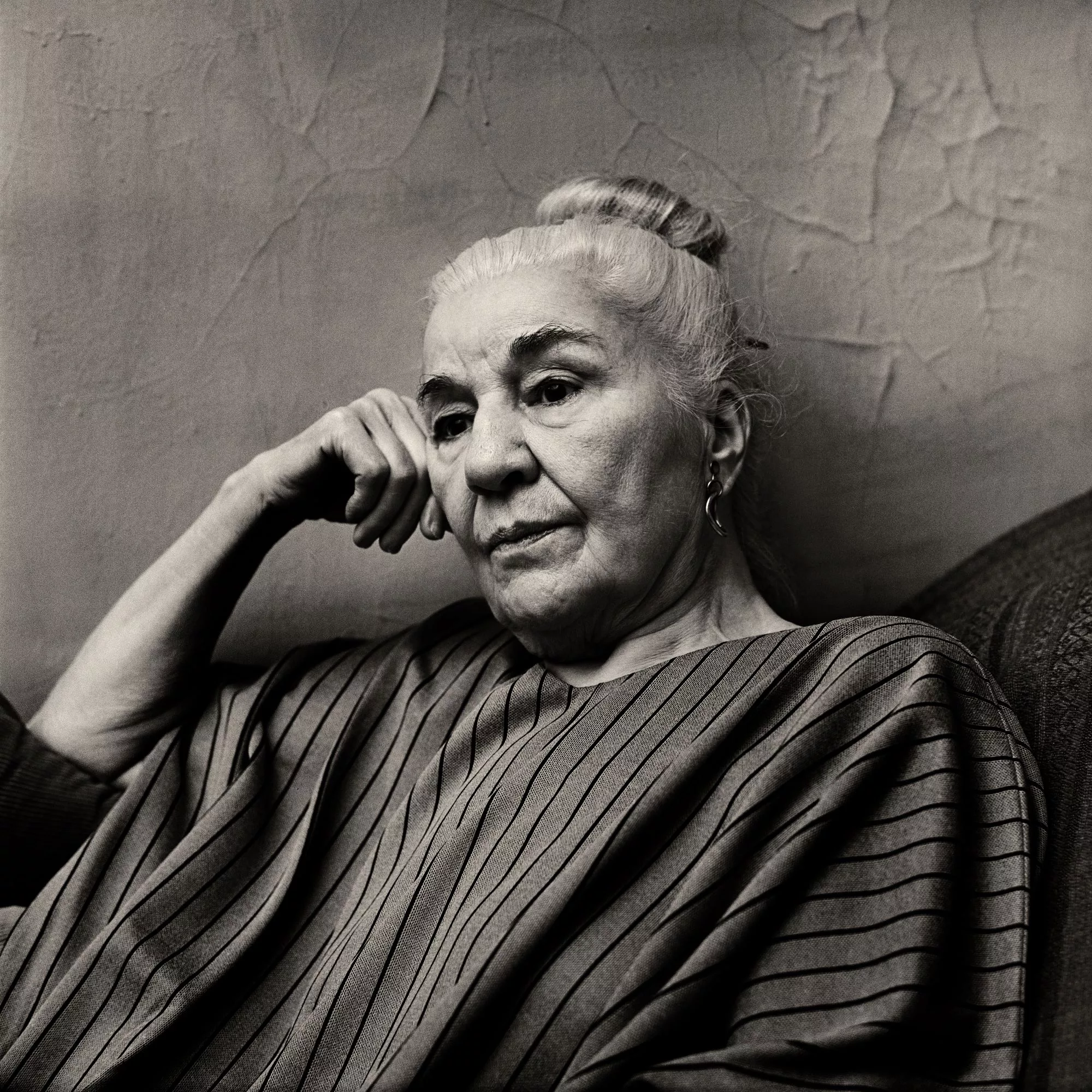

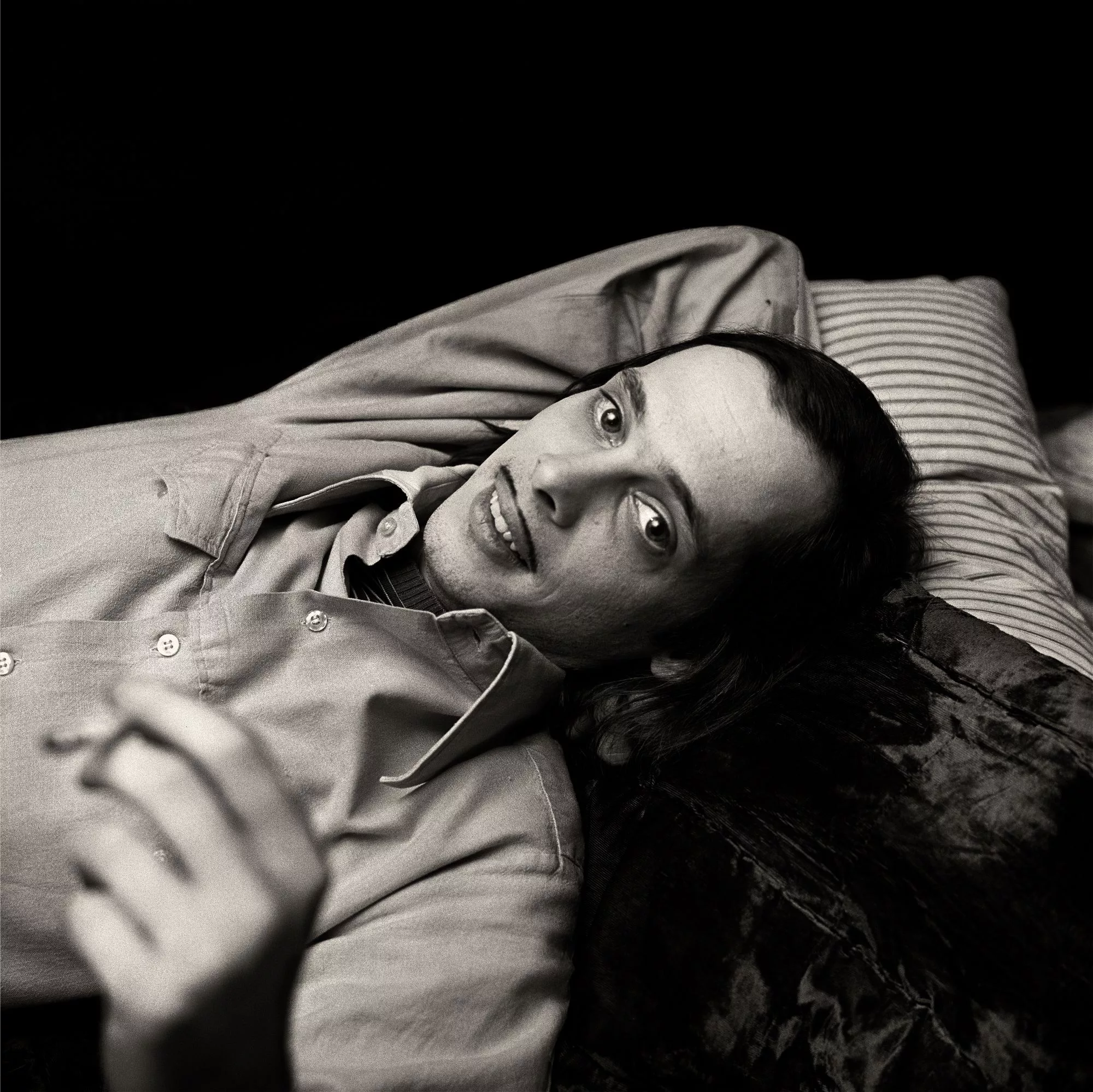

In the gallery, the two series are presented separately. Intimate portraits of friends, lovers, and contemporaries, many of whom are no longer alive, call across the space to the room of the long-dead, all subjects frozen in time by the camera’s gaze. The portraits see the sitters caught in moments of contemplation, potentially about their own mortality, about a life lived and whatever life is left. Photography seems uniquely placed to invite this position; as Susan Sontag – a friend of Hujar, art critic and, here, portrait subject – wrote in her foreword to the first edition of Portraits in Life and Death,

“We no longer study the art of dying, a regular discipline and hygiene in older cultures; but all eyes, at rest, contain that knowledge. The body knows. And the camera shows, inexorably.”

Hujar’s portrait of Sontag shows the writer lying on her back, hands behind her head as if caught in a daydream. This pose is replicated by other sitters. Elsewhere, John Waters lies with one arm behind his head, the other angled towards the edge of the photo, holding a cigarette like he is trying to stub it out on the side of the frame. Hujar, in his self-portrait, lies topless, relaxed, arms raised, revealing all of the intimacy that a bare armpit holds. This repeated pose – quiet, charming, yet still active – offers us a lot of the sitter, their chest and, in turn, their beating hearts pushed to the fore.

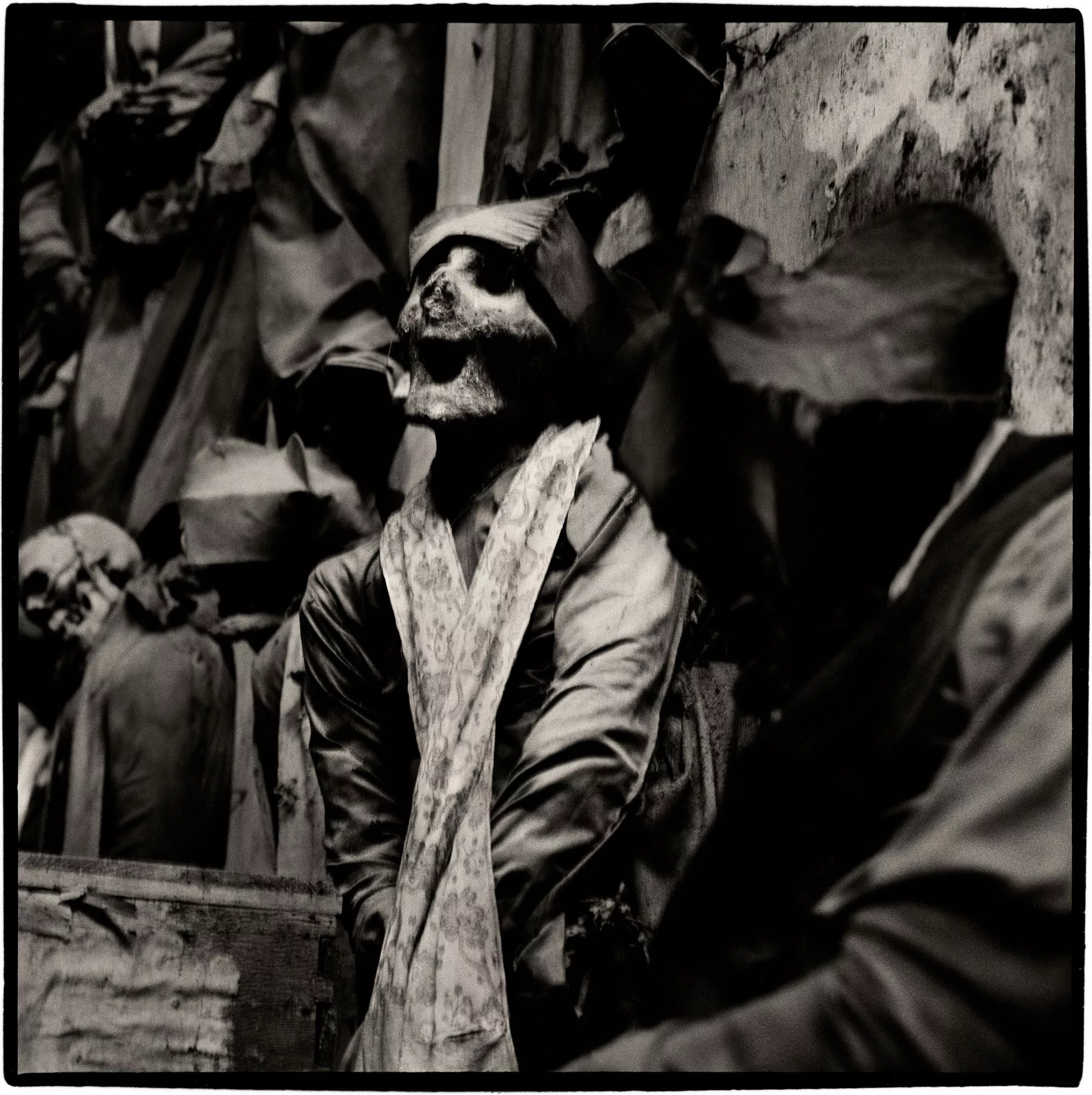

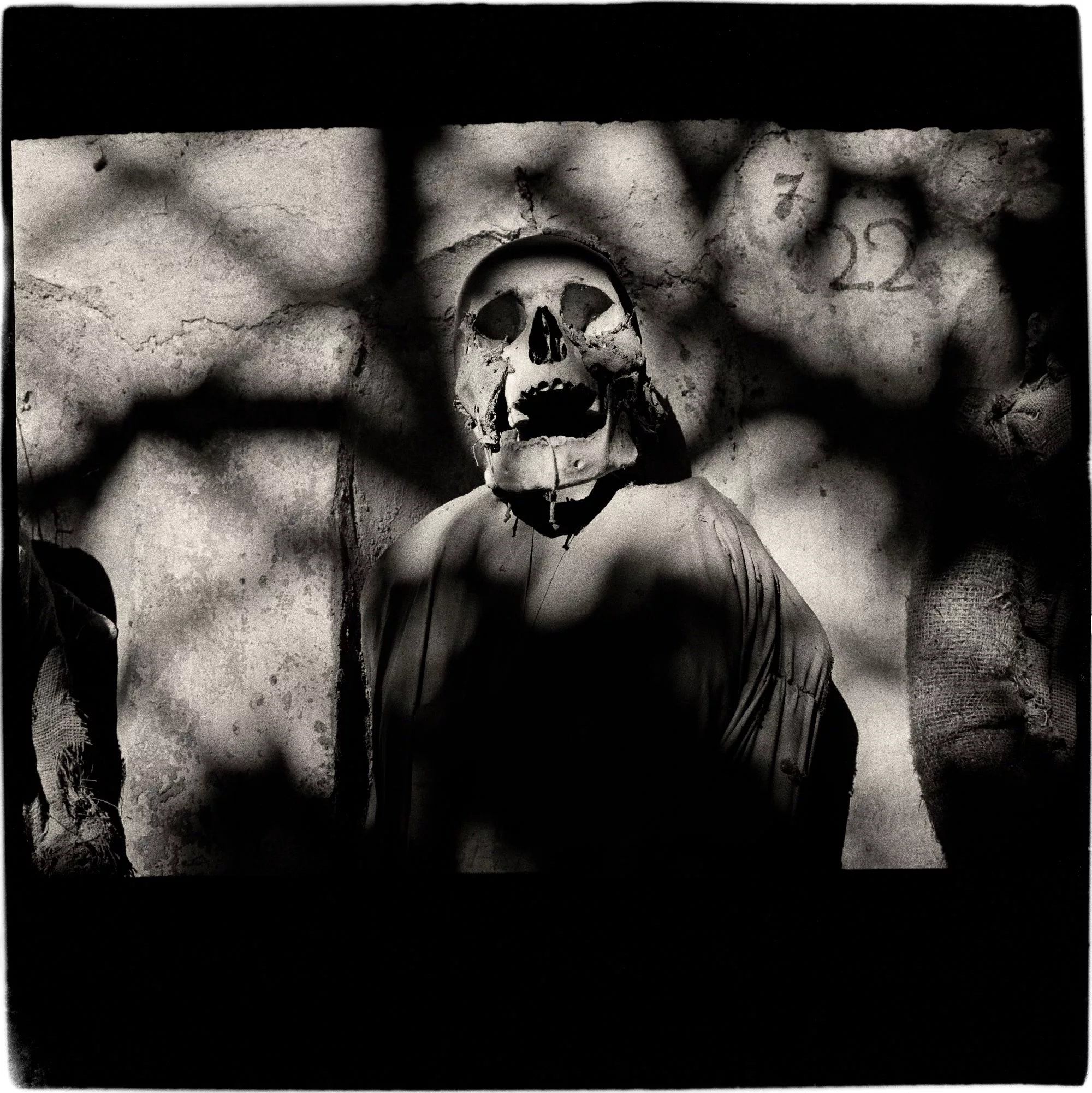

The second series – the catacombs – shows images of partially mummified skeletal bodies, the flesh now evaporated, bones stark. The photographs, however, are angelic. In one, a skull crowned with a bonnet of oversized roses rests peacefully on its side on a bed of ruffles, echoing the contemplative gestures of the other series. While death in the portraits of Hujar’s friends is suggested or implicit, the photographs here deal directly with the reality of death in a manner that is both jarring and deeply emotional.

It’s hard not to think of the death that would have surrounded Hujar at the time of making these images: the AIDS epidemic and vast communities of people whose lives are now only preserved through images. Both series speak to this – how we look death in the face, how we hold the ones we need close to us even after they are gone, and the images and rituals that make this process tangible and which make going on without them possible.

Hujar made space to think not only about the representation of death within photography but also about our capacity, responsibility and durability as an audience. In our current moment, it is impossible to consider these images and ideas of death, preservation and memory in photography without also thinking about the images emerging daily from Gaza and how, societally, we consume death and destruction within our communities so repeatedly that it becomes normalised and we become immune. In all 29 of these images, Hujar manages to capture the aliveness and vulnerability of each subject. This comes as a timely reminder that, for an image to be taken in death, a life must precede it.

Written by Lisette May Monroe