Few others are so dedicated to inhabiting the vision they espouse as the musician Sun Ra. Born under a Gemini sun in 1914, Herman Poole Blount was born and raised in Alabama. Nicknamed ‘Sonny’ from childhood, his early life is clothed in mystery—a fitting disguise for a performer who invented his own identity. Music dominated his childhood as a skilled pianist, and Blount immersed himself in the sonic teachings of musicians such as Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. Teenagehood saw his musicality blossom: he could reproduce songs from memory after seeing them performed, and sight-read music perfectly. This prowess ensured that he danced in and out of various jazz outfits, and toured with none other than his biology teacher’s group in the early thirties. Blount later took over this group, renaming it the Sonny Blount Orchestra, but it was dissolved after several months of touring deemed the outfit unprofitable.

Despite the segregation of the South, Black musicians were in high demand in white society and Blount found consistent work. The tensions ran tall at these concerts; Black performers would be revered for their musical ingenuity, yet were forbidden from fraternising with the audience. Respectability politics were rampant: band members were expected to be disciplined and presentable in order to be accepted into white society.

It was during his time at university that Blount encountered the vision that would transform him into Sun Ra. He is quoted in Space Is The Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, recounting this experience later on. “My whole body changed into something else… I went up… I wasn’t in human form… I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn… they teleported me and I was down onstage with them.” “They” told Ra to stop attending college, because the world was “going into complete chaos”. He would speak through music and the world would listen.

Szwed (Sun Ra’s biographer) explains that “even if this story is revisionist autobiography (it has been difficult to place the date at which this occurred over the years) Sonny was pulling together several strands of his life. He was both prophesying his future and explaining his past with a single act of personal mythology.” In the early fifties, Blount legally changed his name to Le Sony’r Ra. He had long been uncomfortable with his birth name, citing it as a slave name. This change occurred when he lived in Chicago, where he slowly began to realise how African history had been suppressed by European cultures. Ra developed an affinity for Egyptian mythology, the iconography of which went on to heavily influence his artistic practice.

“He was both prophesying his future and explaining his past with a single act of personal mythology”

It was in the late fifties that Ra christened his band the ‘Arkestra’, citing the pronunciation of the word orchestra in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. They began to perform wearing “purple blazers, beanies topped by propellers and white gloves”. Ra began to record the music regularly, and through this increased visibility the band became a thriving hub for jazz experimentalists. At the same time, the beginnings of an Afrofuturist outlook began to take root; Ra claimed that he had been born on Saturn, and was evasive about his personal life in interviews, instead choosing to project philosophical pontifications about the earth and space into his answers.

Unlike other Black political revolutionaries of the time, such as the Black Panthers, Ra chose to respond to the systemic oppression of the Black community by transcending it completely. Where the Black Panthers took up arms in order to defend their communities from the police, determined to incite revolution that was grounded in the present, Sun Ra dreamt of a truly utopian future that had its roots in the infinite possibilities of outer space. Music was the tool he chose to transport his audiences into this world, but he was equally committed to espousing this vision through the surrounding creative mediums at his disposal.

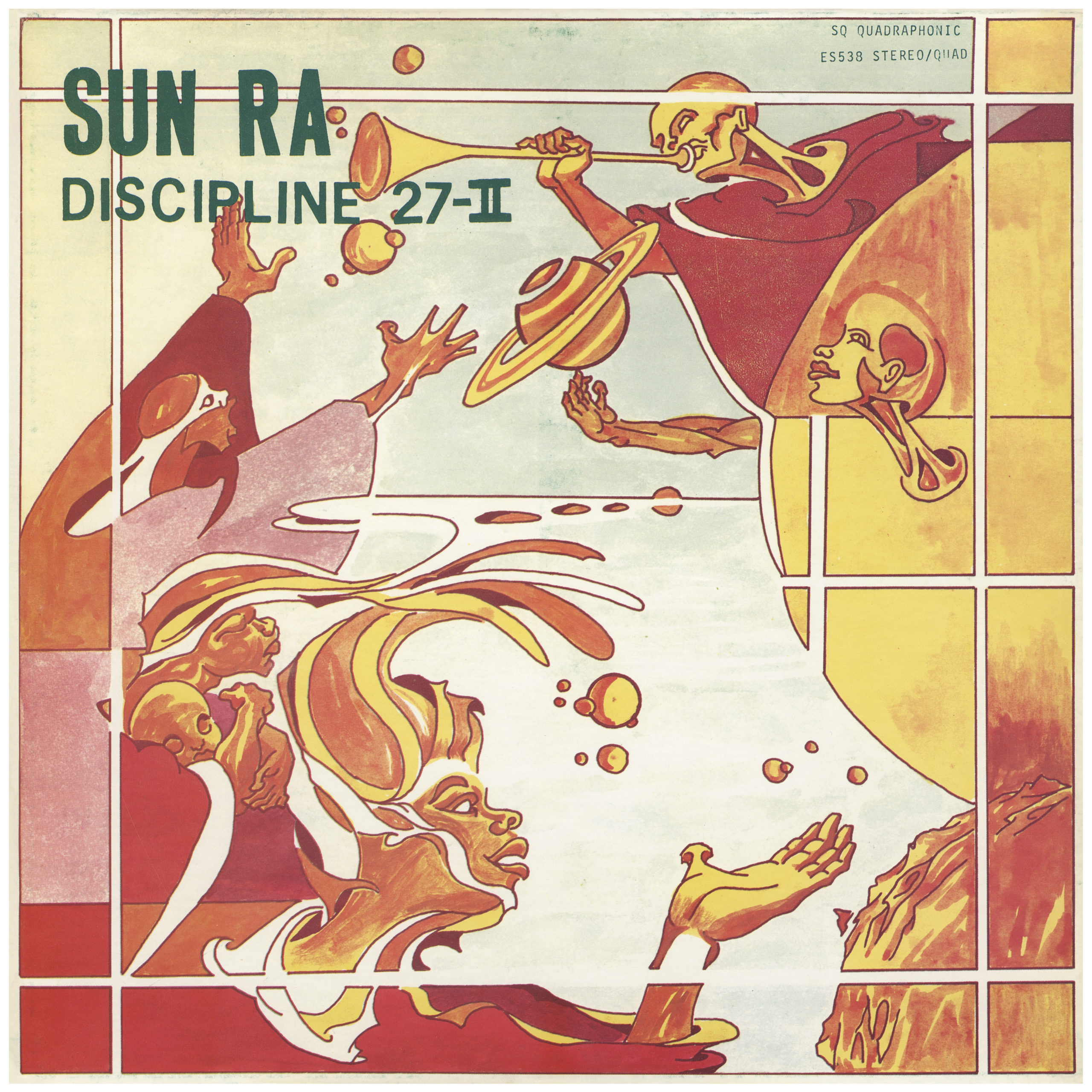

Each album produced by Saturn records depicts a different facet of Sun Ra’s celestial dream. On the cover of Discipline 27-2, fiery hues depict half human creatures which seem to be emerging out of the sun. They spin planets on their fingertips and conjure spherical matter into being. It’s difficult to tell who is birthing who—the human-like figures seem to be at one with the space objects they create. These unified forms continue into We Travel the Space Ways, where music is personified into a writing blue mass, both enveloping towering piano keys while clamouring cymbals sprout out of musical notes. The image perfectly encapsulates the cacophony of sound that Ra was so famous for, and perpetuates his philosophy of performance, that the audience must be at one with the music.

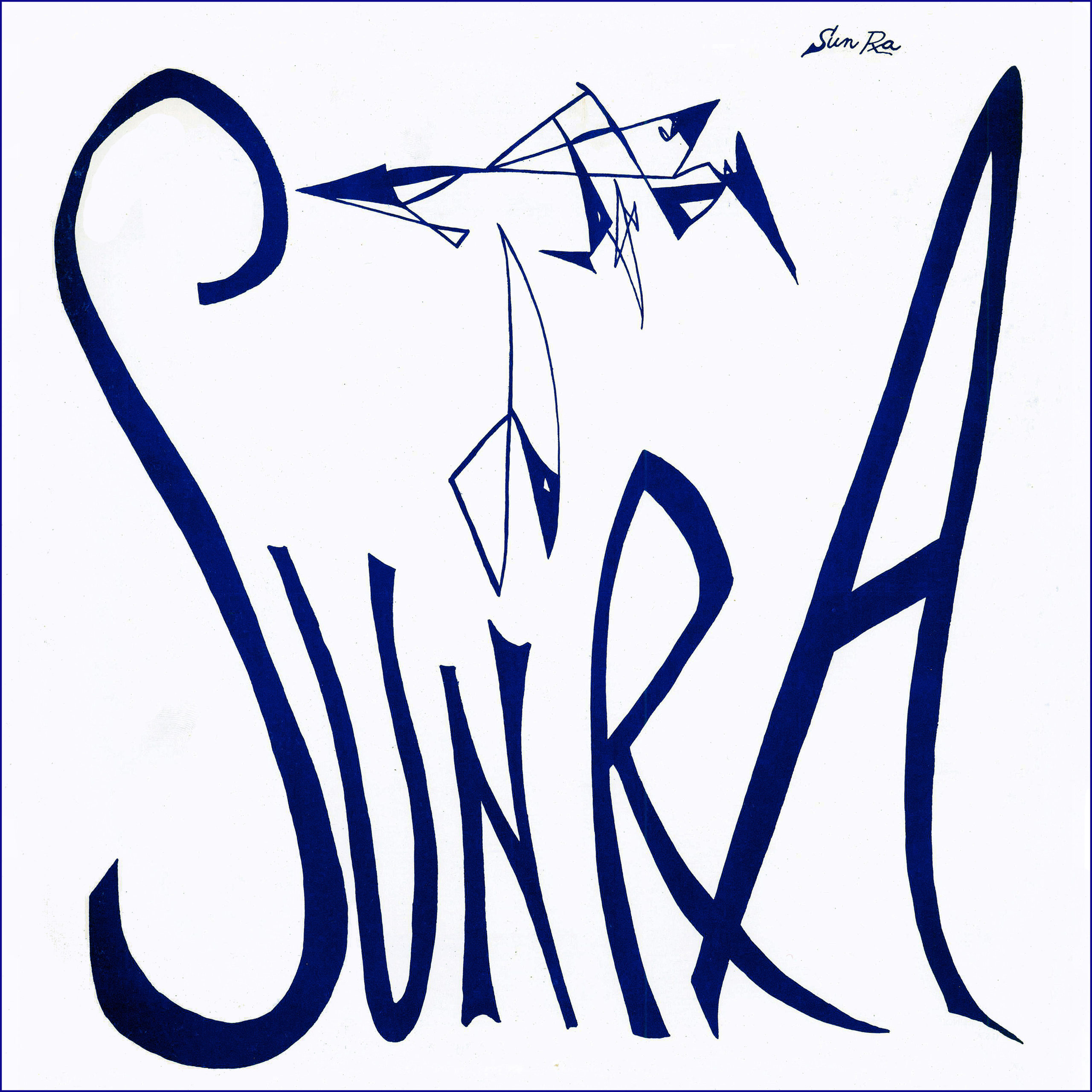

Jazz in Silhouette toys with the boundaries of imagination. Big-breasted figures, seeming both sultry and powerful, float vixen-like above a crater-wrecked planet. The face in the foreground seems to be in a meditative trance, hovering peacefully in the middle of the illustration. The slightly unresolved, sketchy style seems to sing of a land that is transient, and that we as the audience should be lucky to witness. Contrast this ethereal scene with the curving typography of one of Ra’s own works, Art Forms Dimensions, and the minimalist tone of the image is almost jarring.

“Sun Ra dreamt of a truly utopian future that had its roots in the infinite possibilities of outer space”

John Corbett, a curator and teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, explains that Ra made use of the surrealist technique of automatic drawing, where the artist suppresses conscious control over the making process, allowing the subconscious to take centre stage. The sharply delineated shapes above are delicate: “the raw images were re-drawn in ink on boards, which were then used to make metal plates that were finally hand-inked and used to print the covers, painstakingly, one-by-one, at Saturn headquarters.” The print blocks were produced by independent Black businesses on Chicago’s south-side—further evidence of Ra’s commitment to his philosophy.

While many of the designs are created by Ra himself, other artists such as Claude Dangerfield or Laini (previously Sylvia) Abernathy contributed their skills to the movement. Believed to be the first Black woman to be credited as a designer on album covers, Abernathy’s deft ability to translate sound into graphic form was particularly pertinent for sun song, Ra’s 1966 output. Continuing the etching style of Jazz in Silhouette, she abstracts a sun into a scorching force, reflecting the vitality of the Arkestra’s performances.

Ra’s pioneering vision has inspired many contemporary musicians, from jazz legend Kamasi Washington to soul queen Solange. He redefined what experimentation meant, both visually and sonically. Ra’s fascination with both past and future allowed him to mould a very unique aesthetic into being, blending Egyptian symbology with a religious devotion to outer-space. In The Culture of Spontaneity: Improvisation and the Arts in Postwar America, Daniel Belgrad articulates a “coherent aesthetic of spontaneity” which manifested as a political response to bureaucracy, linking bebob jazz to abstract expressionism. Ra embodies this theory.

In the early 1940s, he fought the draft by identifying as a conscientious objector, despite the ostracisation this earned from his extended family. After refusing to take part in alternate service, he was arrested, and debated the judge on points of law and Biblical interpretation. He had been a voracious reader as a child, which informed his abundant intellect as an adult. After several letter writing campaigns led to his release, he returned to Birmingham, embittered. It was likely this experience that encouraged Blount to transcend the world that treated him with such disdain, and metamorphose into Sun Ra, a superterrestrial being who lives on, untouched by injustices of the earth.