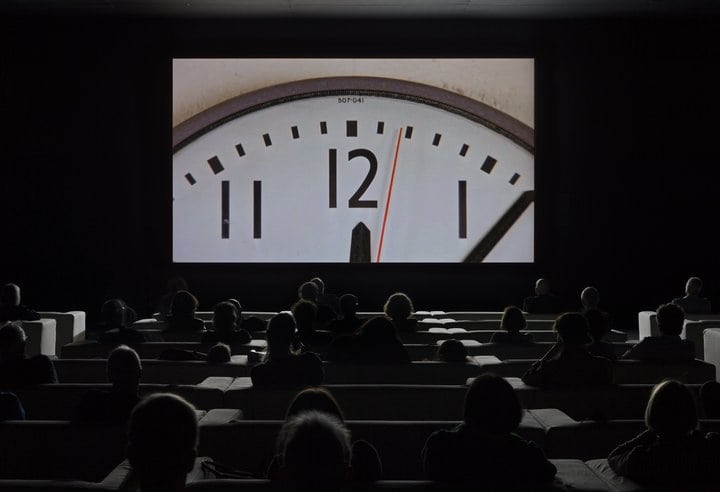

The seconds and minutes tick by in a darkened room. How long do I stay? Christian Marclay’s epic, 24-hour cinematic collage gathers countless movie clips that feature wristwatches, alarm clocks, airport or train-station boards, digital and analogue timepieces (even sundials) and anything else pertaining to time that has been captured on film, all of which are painstakingly edited together into one whole day of clock watching. This work has been widely discussed in terms of its service to film history and the depiction of time itself, functioning as it does as an accurate, if unwieldy clock. However, little has been said about the place of The Clock as a piece of video art, or why we might want to stick with any such lengthy, looping art film for more than the usual, dismissive two or three minutes, max.

Let me set the scene, or scenes. Marclay and a team of researchers collated thousands of film excerpts corresponding to precise moments on the clock (the artist is half-Swiss, after all), often with recurring activities or themes linking the footage—so 7 am is when most people seem to wake up (Michael J. Fox in Back to the Future; Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry) and midday is traditionally when a cowboy comes out of the saloon (Gary Cooper in High Noon). Midnight, or rather the seconds leading up to it, provide the most climactic moments, when all the church bells bong, the clock tower of Big Ben is symbolically blown up in V for Vendetta and Orson Welles plunges to his death off a similar structure in The Stranger

. The minutes just after each hour are also full of incident, with people running late, bemoaning a missed appointment or looking relieved that the bomb they’ve just defused hasn’t gone off.

Astoundingly, every minute past and every minute to every hour of the day seem catered for in Marclay’s movie marathon. Even allowing for a few obscure sources, such as a couple of Chinese-language films and some art-house classics of world cinema, including Wong Kar Wei’s In the Mood for Love, Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru and Ingmar Bergman’s Seventh Seal, most of the snippets are recognizably mainstream or Hollywood fare. This constant flow of samples (a technique the artist has used in many other works, involving both moving images and soundtracks) keeps us glued to the screen and guessing as to what comes next.

The Clock is both addictive and stirring, but it’s almost physically impossible to watch the whole thing straight through, from start to end (one Canadian journalist claimed to have done, although his toilet breaks somewhat negated the feat). I find individual sections of The Clock are hard to recall, even after multiple visits (I have sat with it half a dozen times in various locations, mainly in London and Venice, since when it has been bought by museums around the world). Its impossibility as an act of watching is intrinsic to its breadth and to its meaning as a work of art, in the same way that Douglas Gordon’s 1993 day-long video homage to cinema, 24-Hour Psycho

– an interminably slowed-down version of the 1960 Hitchcock slasher flick—was purposefully uncontainable as an experience.

The Clock also presents us with a simple idea—a film made up of films that lasts a whole day—which actually complicates reality by foregrounding our time spent watching it and what we are doing or not doing with those hours and minutes. Viewed like this, The Clock could be seen to be counting down the precious seconds we have left on the Earth; it’s an existential place to be and there’s not much time left.

This is an extract from Ossian Ward’s Ways of Looking: How to Experience Contemporary Art (Laurence King, 2014). The sequel, Look Again: How to Experience the Old Masters (Thames & Hudson), will be published next year