A conversation on magic, humour and collective rights

One evening in late January, two founding members of the American art-activist group Guerrilla Girls arrived masked-up at London’s Tate Modern in a choreographed take-over of the building. It felt the hippest place to be that night: youth poured in from every direction, queued up for snacks and booze and shuffled in the Turbine Hall to tracks spun by Sister Midnight and fashion designer Pam Hogg (earlier spotted with former Tate director Frances Morris). The event came to a sensible close at 10 pm when the cloakroom shut.

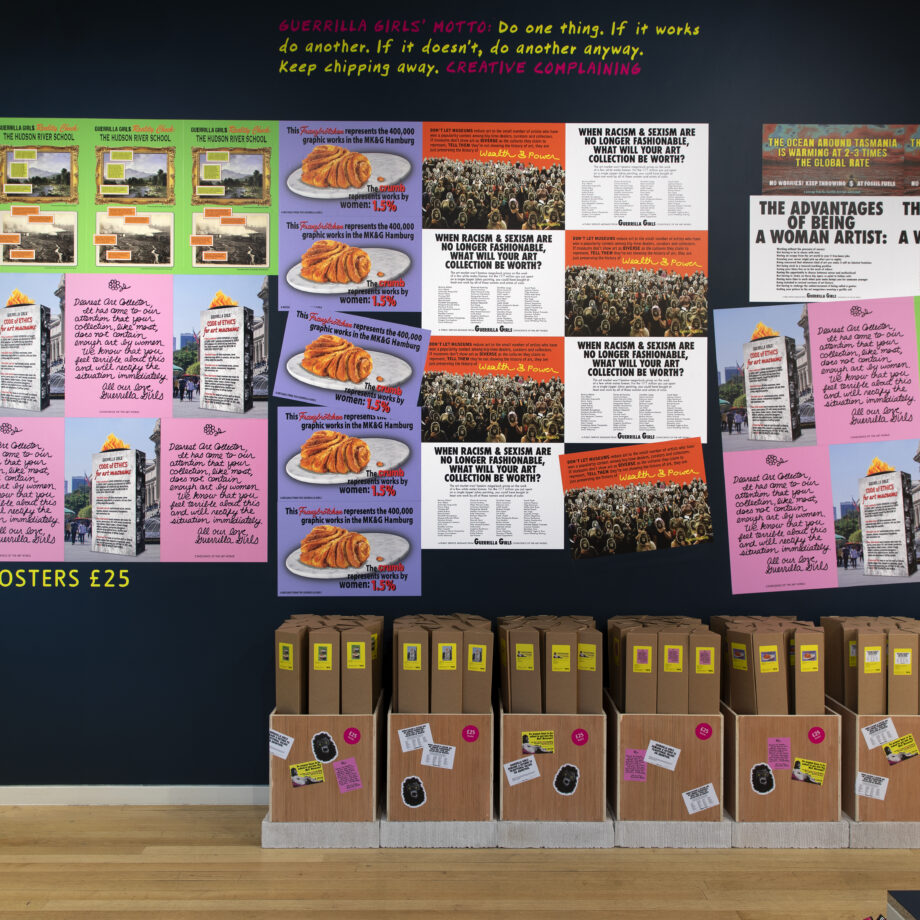

Guerrilla Girls can pull a crowd, especially when there’s a dedicated shop thrown into the mix selling totes, tees, pencil cases and posters, alongside participation for punters that are de rigueur these days. Installed deep inside The Tanks was the Guerrilla Girls Complaints Department, a wall of blackboards where you were handed a stick of coloured chalk to write on an issue you felt strongly about. Across the way, trestle tables were set out for you to stick a message on a pink Post-it in response to the prompt “Dear Art Collector…”

Guerrilla Girls have used these tried-and-tested methods since the 1980s to highlight systemic sexism, racism and corruption in the art world, from what is shown on gallery walls to what is bought, collected, valued and reviewed. They shared this Tate Late night with other art-activists including Sweet Thang zine-maker, Zoe Thompson, the Sisterhood Collective and Black Girl Fest founder, Nicole Crentsil.

The crowds got well stuck in to the engagement, but few if any of the musings I saw on blackboards and post-its that night were truly creative solutions to structural problems. Perhaps this was beside the point. To encourage collective critiquing – even of the institution in which it takes place – throws into sharp relief those regimes where it would be deemed a criminal offence. I’m writing this a fortnight after Russian opposition leader and vocal critic of Putin, Alexei Navalny, perished in Polar Wolf prison in the Arctic in suspicious circumstances. Mourners laying flowers for him at memorial gatherings in Moscow saw them removed by soldiers while they risked arrest.

This difference was further laid bare in a Zoom conversation at Tate Modern between Frida and Käthe, two founder members of Guerrilla Girls (their names are pseudonyms taken from artists Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz) and Pussy Riot founding member, Nadya Tolokonnikova, chaired by DJ/journalist Kate Hutchinson.

“In the US, they’re not going to kill us for what we believe in,” Frida said. For Nadya, “There would not be Pussy Riot without Guerrilla Girls”. The Russian art-performance-protest collective intent on wiping Putin off the face of the earth has engaged in actions that led to the imprisonment of several of its members, including Nadya.

In 2012, the group burst into the Cathedral of Christ The Saviour in Moscow wearing skimpy mini frocks, brightly coloured tights and knitted balaclavas in assorted hues, presented themselves in front of the altar and while musicians bashed out heathen chords on electric guitars the rioters high kicked and punched the air then fell on their knees in mock supplication. “I think it’s important to scream,” Nadya told Tate Modern’s audience.

Punk Prayer took a swipe at the close relationship between church and state while supporting the LGBTQ community, under threat in the autocracy, but it left a sour aftertaste: for Russians, it smacked of past mockeries of the church during the Soviet era and allowed Putin to cast himself as custodian of traditional values.

The trial of Nadya and fellow punks Maria Alyokhina and Yekaterina Samutsevich resulted in sentences of two years in a penal colony where the prisoners had to sew military uniforms. They were released at the end of 2013 (Samutsevich was freed on bail in October 2012).

At Tate Modern, the women from these two opposing nations listened to one another across a physical-virtual divide and generational gap, the Americans in gorilla masks and the unmasked Russian on-screen. They were arguably united in a continuum of protest but rarely seemed to connect.

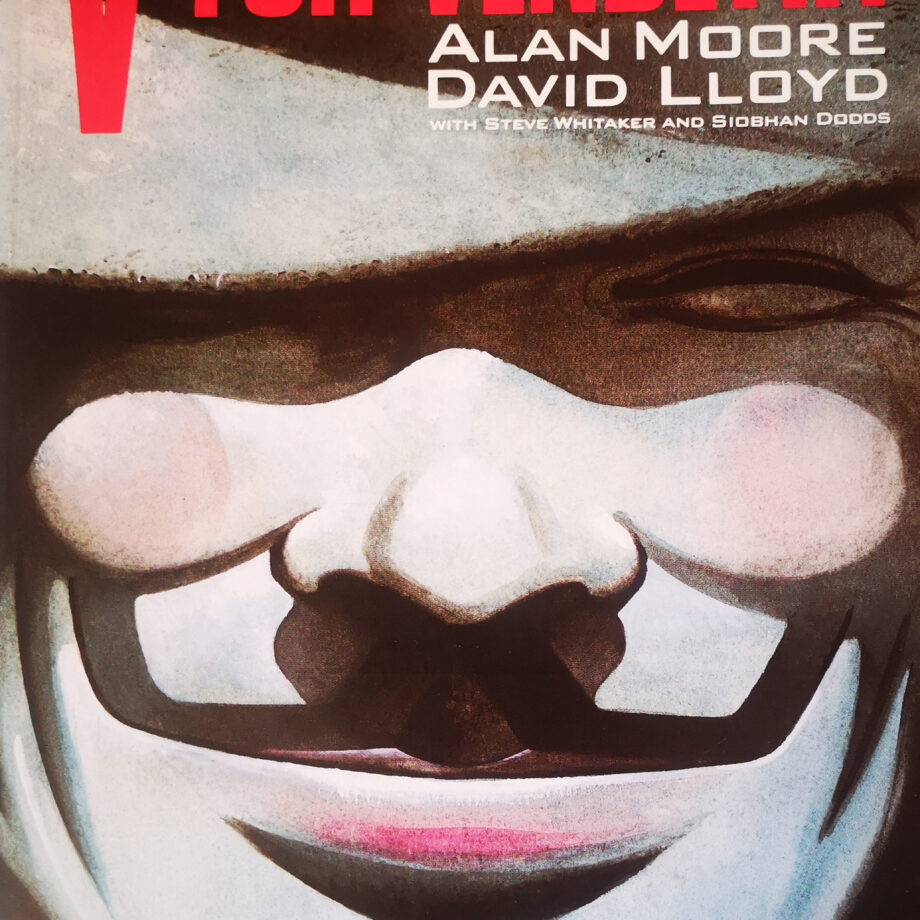

Both use masks, a visual identifier of their affiliations that confers invisibility on the individual, not simply for reasons of protection but also to chime with the collective non-hierarchal ethos. The mask has been adopted by other activist groups in this way, such as the Occupy Movement who wore a Guy Fawkes mask pulled from the cover of Alan Moore’s graphic novel V for Vendetta (1982). “People hide behind the mask […] therefore they can do a lot more than they would if they didn’t have the mask,” one London protestor was quoted as saying in a HuffPost (2012).

The Guerrilla Girls’ use of a particular primate to shield their identity was described by Nadya as ‘brilliant anonymity”. The Guerrilla Girls use DIY posters, hoardings, and collages combined with witty and humorous aphorisms backed up by data to highlight the inequalities in the art world. Their masks effectively emphasise this through the associated masculinity of the image with its associations of King Kong, for example, employed in the service of equality between the sexes.

Pussy Riot, meanwhile, plays more on the disconnect between the terrorist balaclava in neon colours and the loud, proud assertion of their womanhood. Humour rarely gets a look-in. Putin has dubbed them ‘Witches paid by Western Powers’. Nadya tells the Tate Modern audience, “We need to use magic against Putin. Nothing else works.”

There is a sense shared by both groups that the situations are so perilous in their respective countries (now the same country, as Nadya was married in Los Angeles this year) that magic, ritual and symbolic gestures may be their only course of action. “We’re in a very dire moment in the US,” says Frida, who repeated the Guerrilla Girl’s motto: “Do one thing. If it works, do another. If it doesn’t, do another anyway.” Nadya affirms. “An action can help you overcome fear and trauma. It makes you feel useful.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that magic has emerged as a theme in the braid of art-activism, cropping up as a subject in a number of art exhibitions in London, from The Horror Show at Somerset House (2022-2023) to environmental and feminist exhibitions, such as Bitch Magic at Alma Pearl gallery (2024).

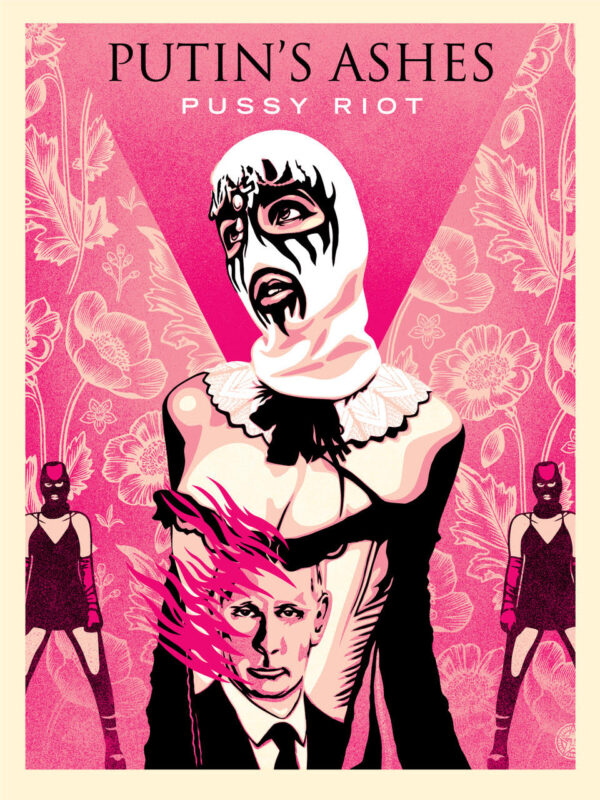

A self-proclaimed advocate of ‘magic activist thinking’, Nadya has long used performance and ritual to challenge powerful patriarchies. In response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, she organised the filming of an army of women of Russian-Ukrainian heritage dressed in scarlet balaclavas and black negligees with Russian Orthodox crosses strung around their necks. They carry a fur-trimmed panel with a red button and the words, ‘This button neutralises Vladimir Putin”. When pressed, an alarm sounds, and the film cuts to a ten-foot-high portrait of the president going up in flames, its ashes collected in a glass vial by the artist.

Putin’s Ashes was shown at the Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in Los Angeles in 2023. For anyone who has attended the burning of an effigy or watched the execution scenes in the televised version of A Handmaid’s Tale the film gives you a powerful frisson of recognition. For Nadya, the portrait was a substitute for Putin’s body. “This is the art that is a hammer that shapes reality,” she remarked.

“In all magic, there is an incredibly large linguistic component,” wrote Alan Moore, who strongly believes in the close relationship between magic and art and words as spells. The Guerrilla Girls are masters of snappy texts that can be scaled up or down according to need. “We make street posters as big as this building or as small as this chair,” they told us. They make them difficult to ignore through their humour. “Humour has always been used by marginalised groups as a weapon against oppressors. It makes you feel good and attracts attention.” A well-known example is: “Do Women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” exposing the fact that less than 5% of artists in the modern art section are women, compared to the 85% number of nudes that are female.

In a separate interview, Nicole Crentsil asked the Guerrilla duo why their activism still resonated forty years after their formation. “We’re still doing it,” one responds. Her mate adds, “One hundred years of feminism is not equal to millennia of patriarchy”.

They went on to describe the evolution of their activism: “A certain social consciousness has changed. When we started in 1985, an art collector said women and people of colour are not creating works of contemporary art dialogue. No one would say that again; racism and sexism have taken different forms now. We didn’t foresee art as an investment. The stream of art is now controlled by a few powerful people. We try to make art that can’t be collected that way.”

Frida throws out a question to the Tate Modern audience: “How many of you can afford to buy art?”

No one raises a hand.

“Art is monetised. Art has become the Olympics where there’s only a few winners. Art is a community thing, not a competitive thing,” says Käthe, calling for more cheap art that everyone can own. This will be contradictory advice for fundraisers who have filled out an Arts Council National Lottery Grant application form, as a strict ACE guideline is that artists are properly paid for their work. It would have been enlightening to hear how cheap art can also support the artists who make it. I left Tate Modern feeling there were many such questions unanswered, thinking that they didn’t join up. Currently, on Russia’s wanted list, Nadya has made a home in the US and taken up causes relating to reproductive rights, with an action staged in the state of Indiana, where abortion is banned. “God Save Abortion” was Pussy Riot’s latest sung contribution. As racial inequality persists in the States, with well-publicised murders of black men at the hands of the police, and as an election with the same 2020 candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, is increasingly likely again this year, democracy in the US looks fragile. “There’s always more villains around,” said Frida at Tate Modern. How far will activists succeed in stalling them? Only a magical crystal ball will tell us.

Written by Deborah Nash