On 25 October, the eighth edition of the Aké Arts and Book Festival, usually taking place in Abeokuta, Ogun State, began its programme. This year, it has gone online with its events involving more than 400 writers, poets, visual artists, musicians and performers. The digital edition was organised to keep people safe from the spread of coronavirus, but now it keeps audiences away from the threat of violence on the streets, following the murder of #EndSARS protestors amid mass demonstrations calling for the dissolution of the notorious SARS police unit and an end to police brutality.

The #EndSARS movement began on Twitter in 2017 following growing concern about SARS activity, and evolved into demonstrations across Nigerian cities in October; soon after the government announced it would disband its SARS (Special-Anti Robbery Squad) unit to placate protestors. However, Muhammadu Buhari’s government has made similar promises in the past.

The #EndSARS movement is being led by young Nigerians, as it is them who have also suffered the most from the abuse inflicted by SARS. The unit has targeted men, particularly young men, and especially those who appear to have social status, money or power. SARs have been involved with harassment, kidnapping, extortion and murder. “Young Nigerians have had enough. And unlike their parents, they are no longer afraid”, writes journalist Yinka Adegoke.

- Alexis Chivir-ter Tsegba

At Aké this year, the main exhibition is also led by young Nigerians; curator Byenyan Jessica Bitrus has selected six young artists among her peers. “As a young curator myself it was important for me to showcase young, creative African talent on a global scale because we need to support each other now, more than ever, to ensure that our voices are heard.” Bitrus explains, in recognition of the need for solidarity within Nigeria and across the continent. “If you look at the current wave of recent protests across the continent you’ll understand that when Nigerians say #ENDSARS or #ENDPOLICEBRUTALITY we’re not just speaking for ourselves, we’re also speaking for Kenya, for South Africa, for Zimbabwe. When our Namibian sisters say #SHUTITALLDOWN, we join them in sounding the alarm because they’re speaking for us too.”

For the first time since its inception, the exhibition at Aké, titled African Time, includes artists from other African nations: Nigerian artists Alexis Chivir-ter Tsegba and Fidelis Joseph are presented alongside Kenyan artists Peterson Kamwathi and Jacque Njeri, Denyse Gawu-Mensah from Ghana, and South Africa-based Zwelethu Machepha. “Our histories are intertwined and in order to be able to rebuild Africa into our ideal continent, we need to continue to lean into each other and fight this fight together—especially now.”

Within the larger festival framework, the exhibition is conceived as a platform for supporting creative talent in the visual arts and building an inclusive community; Bitrus’ work for African Time reflects this approach by presenting more established artists like Kamwathi alongside artists who are new to the international audience who can now access this exhibition online. Though the digital mediums thrive in a digital exhibition, Bitrus also makes rooms for more traditional art forms, but each of the artists speak to the theme of time, viewed as “an evolving concept, a continuum,” Birtus explains.

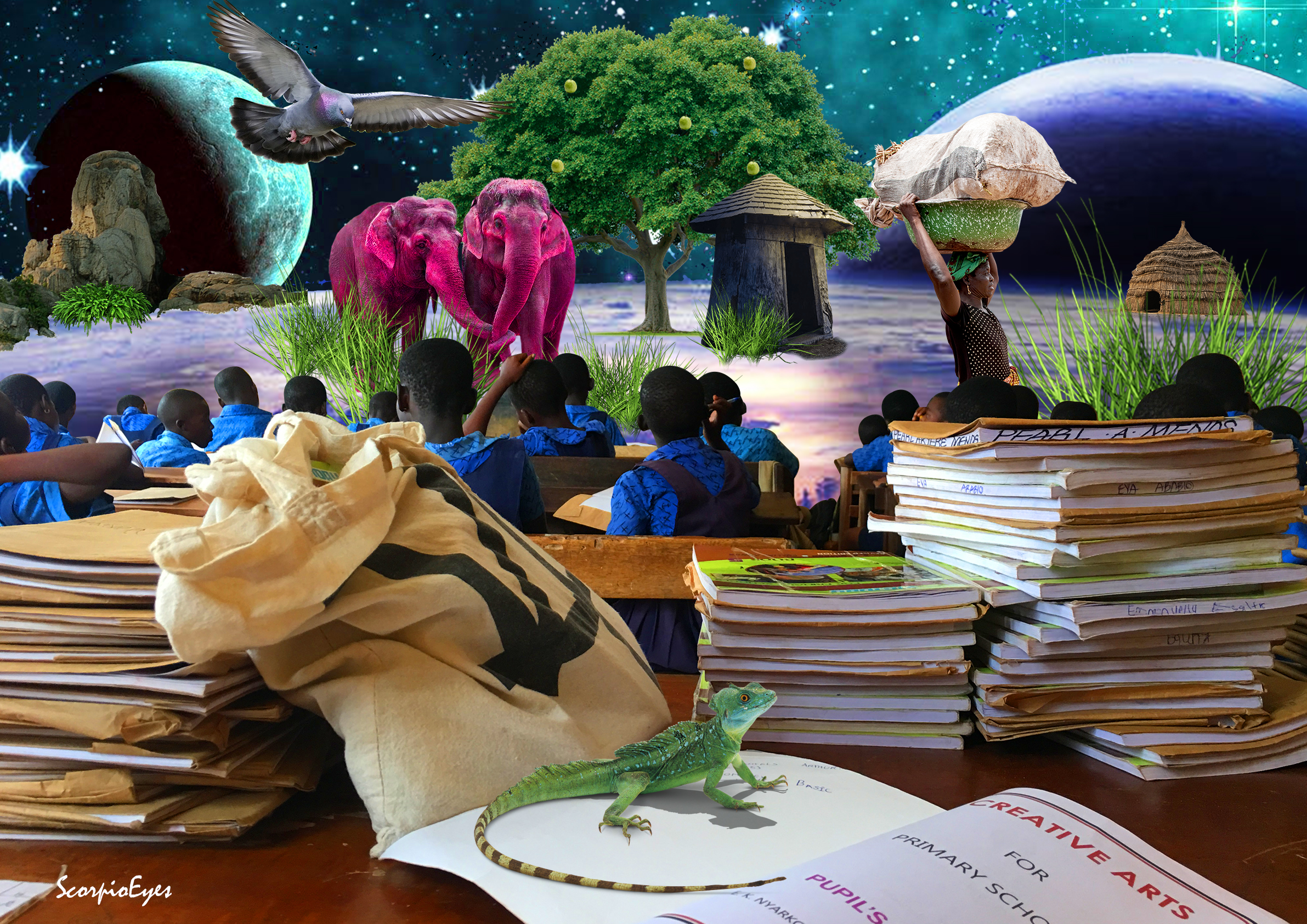

In Gawu-Mensah’s work, for example, folktales from Ghana, an oral tradition, are translated into the digital; meanwhile in Njeri’s MaaSci series, the Massai tribe of Kenya are depicted as the leaders of a new African Society in a technologically-advanced future. In the surreal, digital collages of homegrown talent Tsegba, spiritualism meets consumerism and sexuality, and the future is also the space to envision “what a truly inclusive and Pan-African society could look like.” It is these works that renew hope in “an African Utopia”, as Birtus puts it.

“A lot of us are still moving around in fear and anger because we do not feel protected”

Writing from Lagos, where on 20 October, unarmed protestors were shot at by police, Bitrus describes the atmosphere as “tense and uncertain. A lot of us are still moving around in fear and anger because we do not feel protected. We’re all simply just trying to survive and doing our bits to ensure that peace is maintained, despite the disappointment we feel.”

Yet what is striking about the atmosphere of this online exhibition is its unbridled sense of hope, whether it’s the dreamlike, iridescent beauty of Tsegba’s compositions or the Kamwathi’s elegiac figures, which seek a better life through movement. The works convey a kind of rhythm of restorative faith that things can—must—be better; that change must originate within but that it will be physical. It is the same feeling that keeps protests broiling as Nigeria’s young generation push for change. African Time exists too as “a reminder that as Africans, we are part of each other’s histories and experiences, that we belong to each other.”