This year marks the centenary of women getting the vote in the UK, but the gender divide in the art world is certainly not over. Just twenty-two percent of solo shows at major London non-commercial galleries last year were by women, and they accounted for three percent of auction lots in the top ten highest-grossing sales at Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Evening Sales in 2017, according to research by the Freelands Foundation. It was also found that female art school staff were likely to be paid less than male colleagues.

There is a greater conversation than ever before around the representation of women in the cultural sphere and beyond, which of course involves looking back at their historical representation too. This week it was announced this week that Frieze London is to launch an exhibition dedicated entirely to female artists, and there are many all-female shows opening in the capital in the coming months. One of these is a major exhibition of three avant-garde female artists from the 1960s and 1970s, which has just opened at Thaddaeus Ropac London.

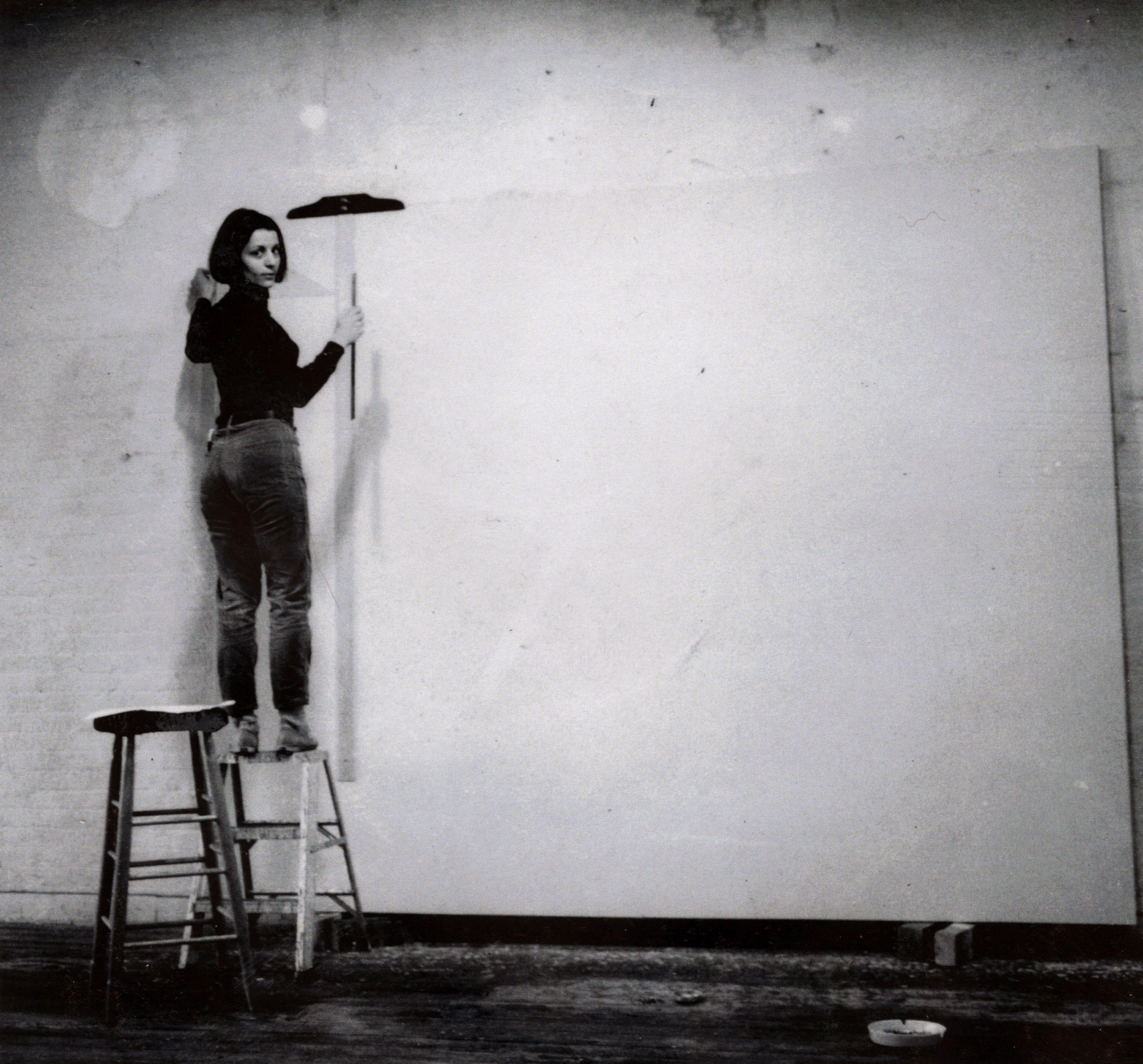

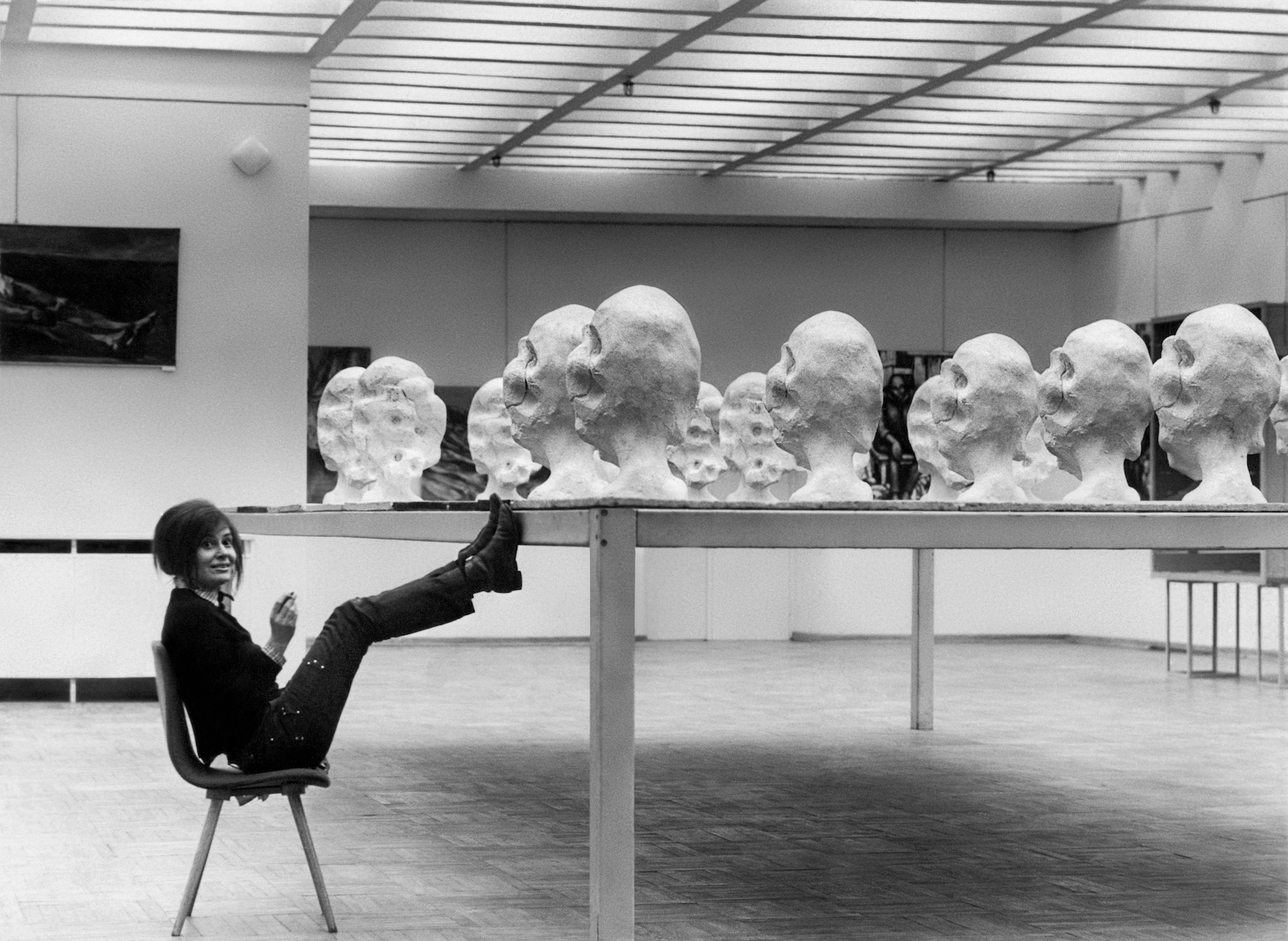

- Left: Rosemarie Castoro "Land of Lashes" archival photograph, 1976; Right: Wanda Czelkowska Self Portrait, Early 1970s B&W photograph

“Despite the distinct political and geographical situations of their backgrounds, they share a radical sensibility and a complete commitment to their craft”

Wanda Czelkowska, Rosemarie Castoro and Lydia Okumura are brought together in Land of Lads, Land of Lashes, where the common threads between their large-scale, site-specific sculptural pieces emerge in their interest in the multidimensional environment and surreal anthropomorphic form. Despite the distinct political and geographical situations of their backgrounds, hailing from Poland, America and Brazil respectively, they share a radical sensibility and a complete commitment to their craft. The exhibition represents a historic moment for the three artists. “When people see the show now, they suddenly get it. They see that this is important work,” the show’s curator, Anke Kempkes, observes. “It’s so rigorous, radical and innovative, but they did not get the recognition that they deserved.”

Wanda Czelkowska, the oldest artist in the show, is still active today. Growing up in Poland under communist rule, and then under Stalinism, there were limitations to the information she had access to from behind the Iron Curtain. Kempkes tells me that Czelkowska studied socialist realism at art school, and “right from the start she mocked this landscape; she was not conforming. She had a resistance to the system and to the politics, and she wanted to go her own way.” In 1963, she was invited to the Paris Biennale for young artists—the first time she was allowed to travel. Here she received an invitation to stay in Paris and not go back to communist Poland. “Her path could have been very different. But she was very much a studio artist, she really lived in her studio and it was her universe. She couldn’t imagine leaving. It’s very interesting in terms of rejecting the domestic life of the woman, of the family.”

“She was very androgynous in her character, very tomboyish. She was into Yves Saint Laurent, and quite glamorous in communist Poland“

Kempkes describes how in Poland there was no art market—at least, not in a traditional sense. However, Czelkowska was able to make work that went straight to national museums, and she also could enter and win state prizes, which led to her continual national exhibitions and exposure. In 1971, she made a giant signature piece of a table measuring eight by four metres, with her sculptural heads displayed upon it. “It is still so contemporary, very gutsy, very creative, so audacious. It looks to brutalism, and is not very feminine,” Kempkes recounts. “She was very androgynous in her character, very tomboyish. She was into Yves Saint Laurent, and quite glamorous in Communist Poland.”

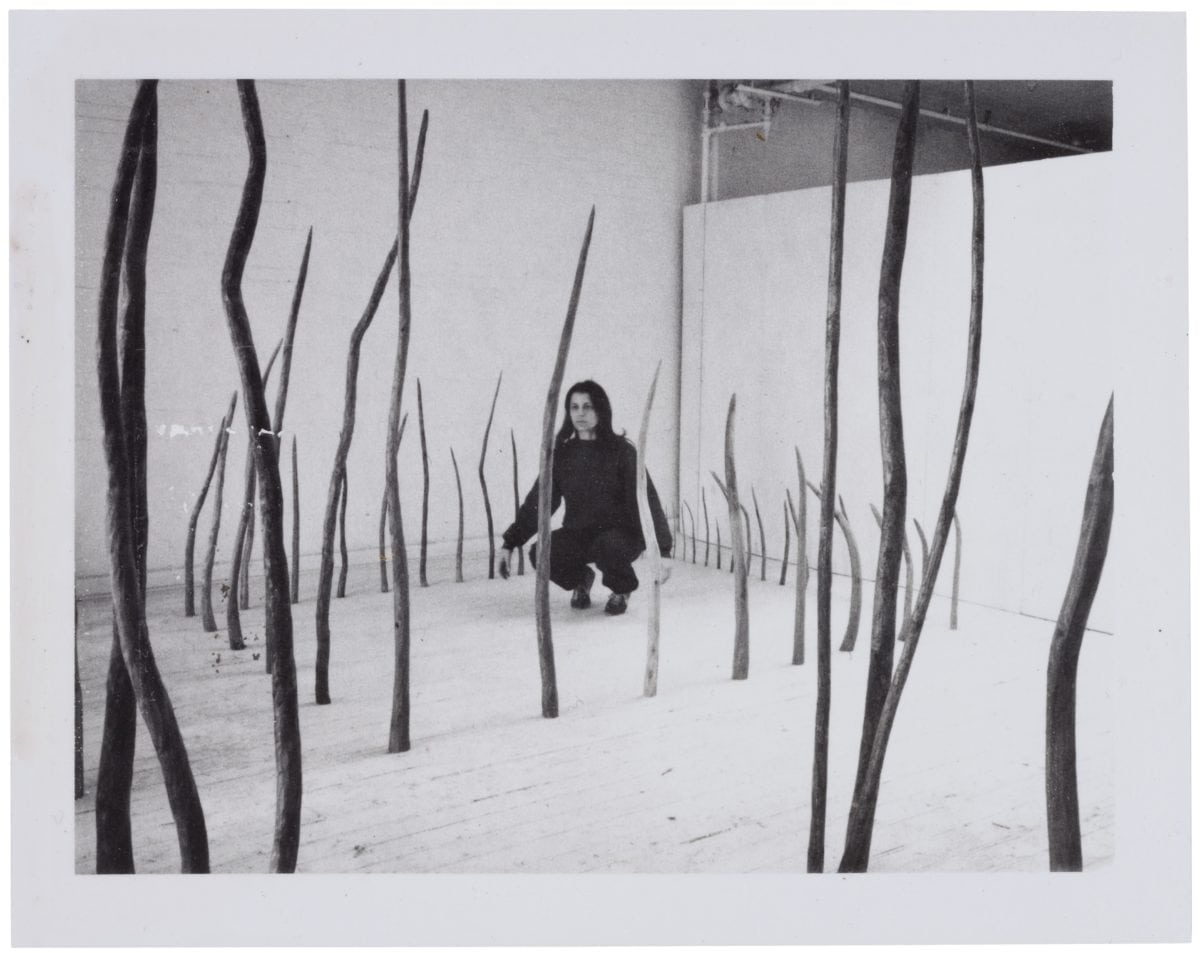

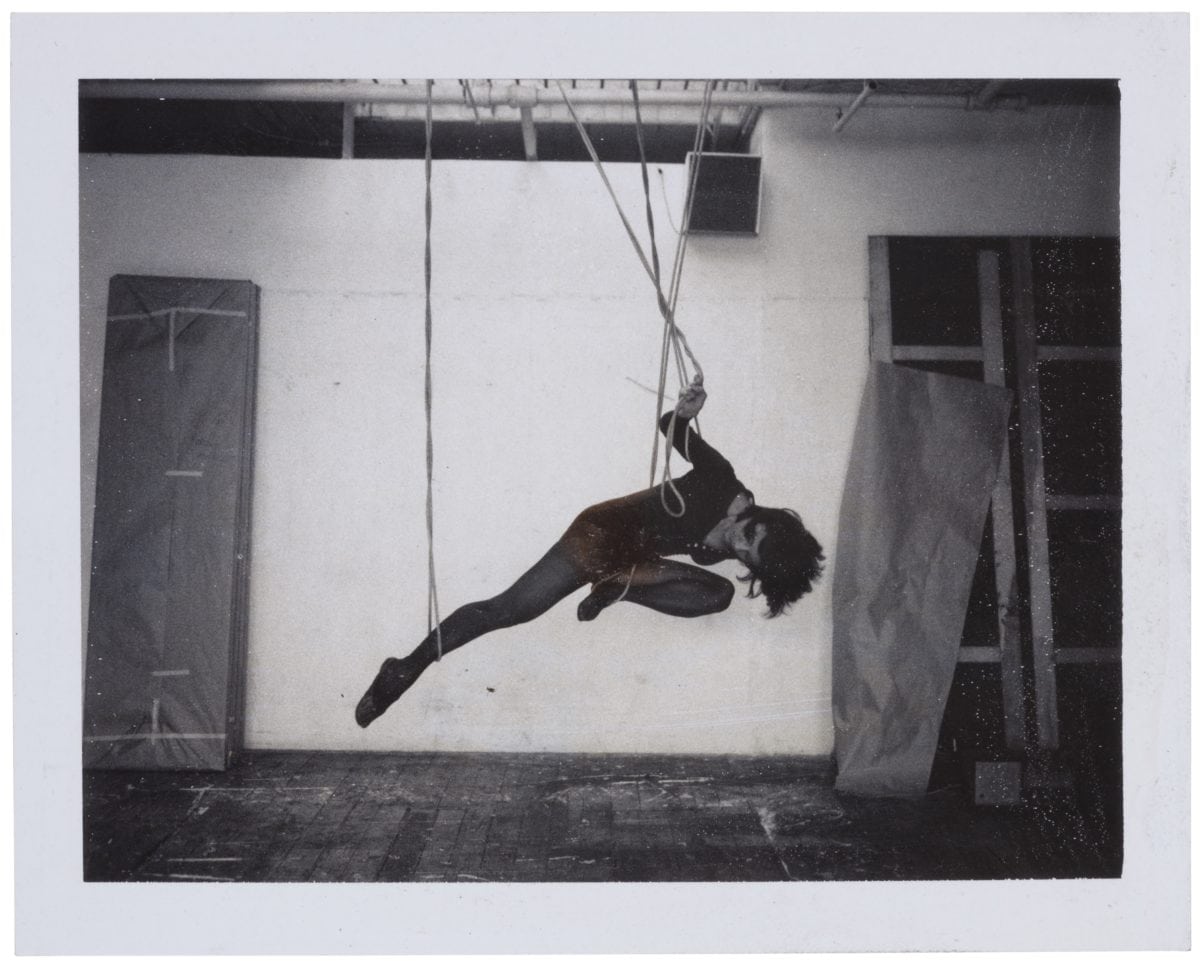

Czelkowska‘s studio was in an old seventies factory, a huge place where she is still based. Rosemarie Castoro similarly worked from 1964 in the same loft studio in the heart of SoHo, Manhattan, until her death three years ago—a stability that is increasingly rare these days as rent control has all but disappeared, and market-led property booms leave little space for artists to survive. Castoro’s studio acted as a social hub for the minimalist and broader creative scene of the 1960s in New York, and she was in a relationship at the time with the minimalist artist Carl Andre. She once said, “My studio is my container of ideas, a laboratory, an incubator.”

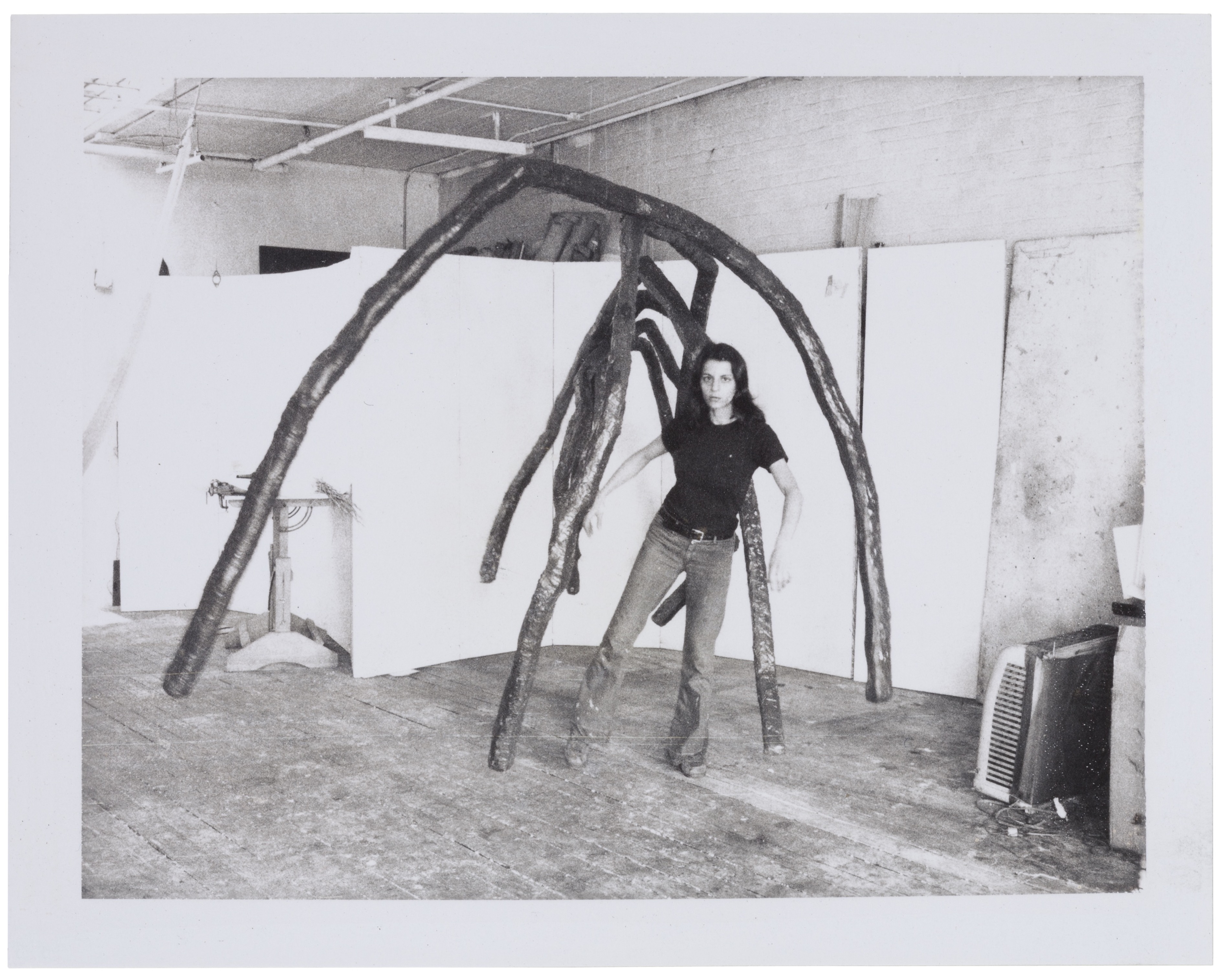

- Rosemarie Castoro working (or performing) in her SoHo studio, New York 1970s

“It was almost more difficult for women artists in New York in the fifties and sixties than Brazil or Poland. It was a very sexist scene”

Initially trained as a dancer, she moved away from the collective creative troupe mentality, wanting to have more control over the work that she produced. “Interestingly, all three artists lived for the most part without family—it was a bachelor lifestyle—completely dedicated to their work,” Kempkes explains. “These days, many female artists try to split their time between work and family, but I think that the older generation needed this absolute focus: they had a complete determination around the work and the studio.”

It was a determination essential to each artist’s survival, and Kempkes relates how the iconic Tibor de Nagy Gallery told Castoro quite simply, “We don’t show woman artists.” Women were unable to gain the same exposure, and not getting that first platform meant then not being included in later museum shows. The repercussions of this chain of historic under-repesentation is still evident today. “I would say that it was almost more difficult for women artists in New York in the fifties and sixties than Brazil or Poland,” she argues. “It was a very sexist scene.”

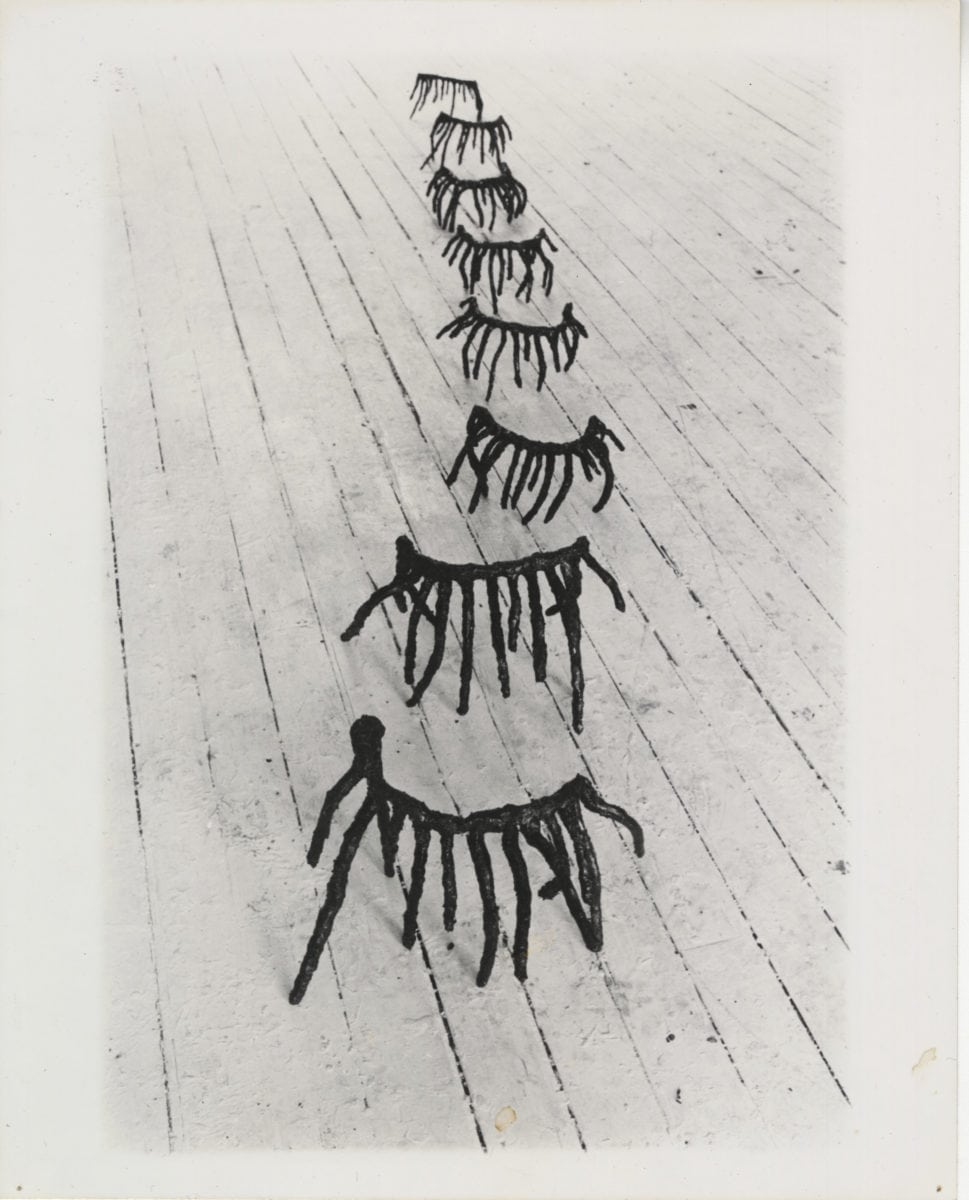

In 1970, Castoro abandoned colour—a political reaction to the Vietnam War. She started to experiment with conceptual works like concrete poetry; by 1971 Tibor de Nagy had changed their policy, and she had her first show with them. She was also part of several group shows that Lucy Lippard curated at that time, and began to move more into sculpture and installation. She used a broom to create giant brushstrokes on wall relief works, in a process felt highly performative. “All her life she was performing, and it’s almost like a stage that the sculpture created for her,” Kempkes adds.

She then moved into making more organic epoxy sculptures, diffusing the minimalist language of the time with gender politics, provocation and sexuality. She created the title works of the show: Land of Lads and Land of Lashes in the mid-seventies. “You have these great eyelashes. It’s a bit creepy, a bit abject: they look a bit like spiders,” says Kempkes. “These works really expand our understanding of minimalism in a radical way.” Her perspective on the three artists is deeply personal, having worked closely with them for almost a decade.

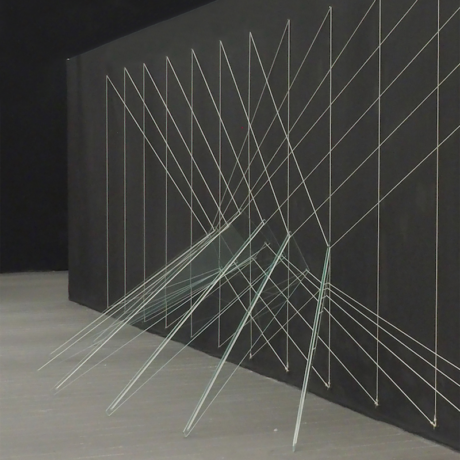

The third artist on show is Lydia Okumura, now in her seventies and still working. Born in Sao Paulo to a Japanese immigrant family, her grandfather was part of the labour influx from Japan at the time, which made up the biggest population outside Japan. “She wasn’t really looking at the hero artists of Brazil, who she found to be primarily part of the elite. Instead she was more interested in Japanese art at the time, and exhibited work at the Tokyo Biennale in 1970.” In 1973 she was invited to New York on a scholarship, at a time when the military dictatorship in Brazil made it difficult to leave the country. But still young and just out of college, she was allowed to leave for New York—and was then able to make it her home.

Okumura showed at five Sao Paulo biennales in the 1970s, and in 1984 she had a solo show at the Sao Paulo Museum of Art, designed by Lina Bo Bardi. She created over forty sculptural environments for this, and took over the whole museum. Working entirely in-situ, she is able to make remarkable works out of almost nothing: wire, string, glass, wall paint… However, as Kempkes points out, “She had quite good exposure, but it was not the same as her male minimalist peers at the time.”

“Working entirely in-situ, she is able to make remarkable works out of almost nothing: wire, string, glass, wall paint…”

In 1980, Ana Mendieta co-curated a show called Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists at AIR Gallery—“it’s remarkable, really, a title like this would never be used today”—and Okumura was included in it. “It was the moment when she then realized that she was above all marginalized, not only as a women but as an immigrant. It was a huge challenge,” Kempkes says.

Each artist dared to take up space with their work, playing consistently with scale and perspective, and engaging directly with the architectural specificity of their environment. Kempkes describes to me how Castoro once aptly referred to herself as a giant woman inside her SoHo studio in New York, outgrowing and protruding from the building itself. It is an image that is also reflective of the difficulties that all three faced as women in a resolutely man’s world, pushing against constraints to claim their place.

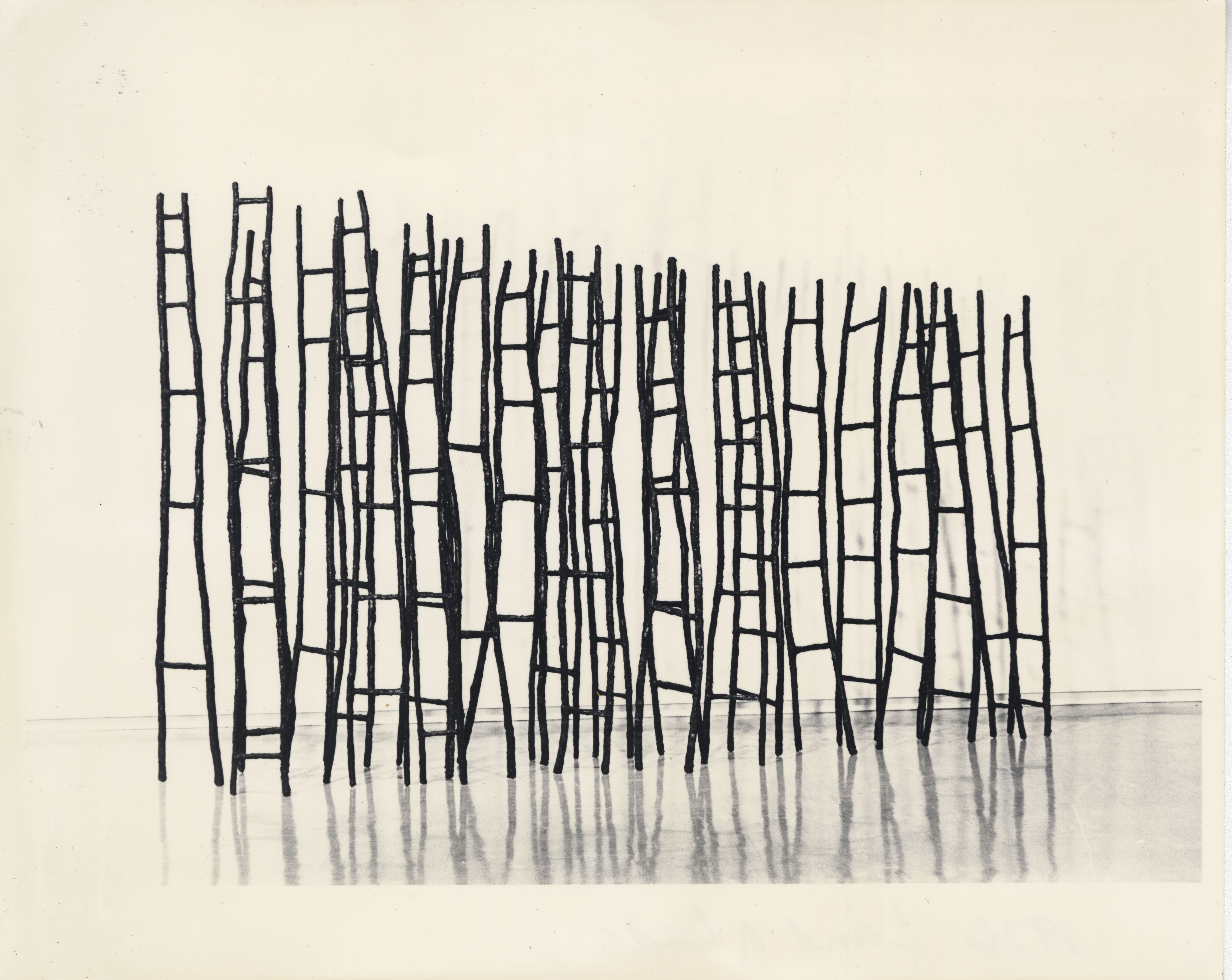

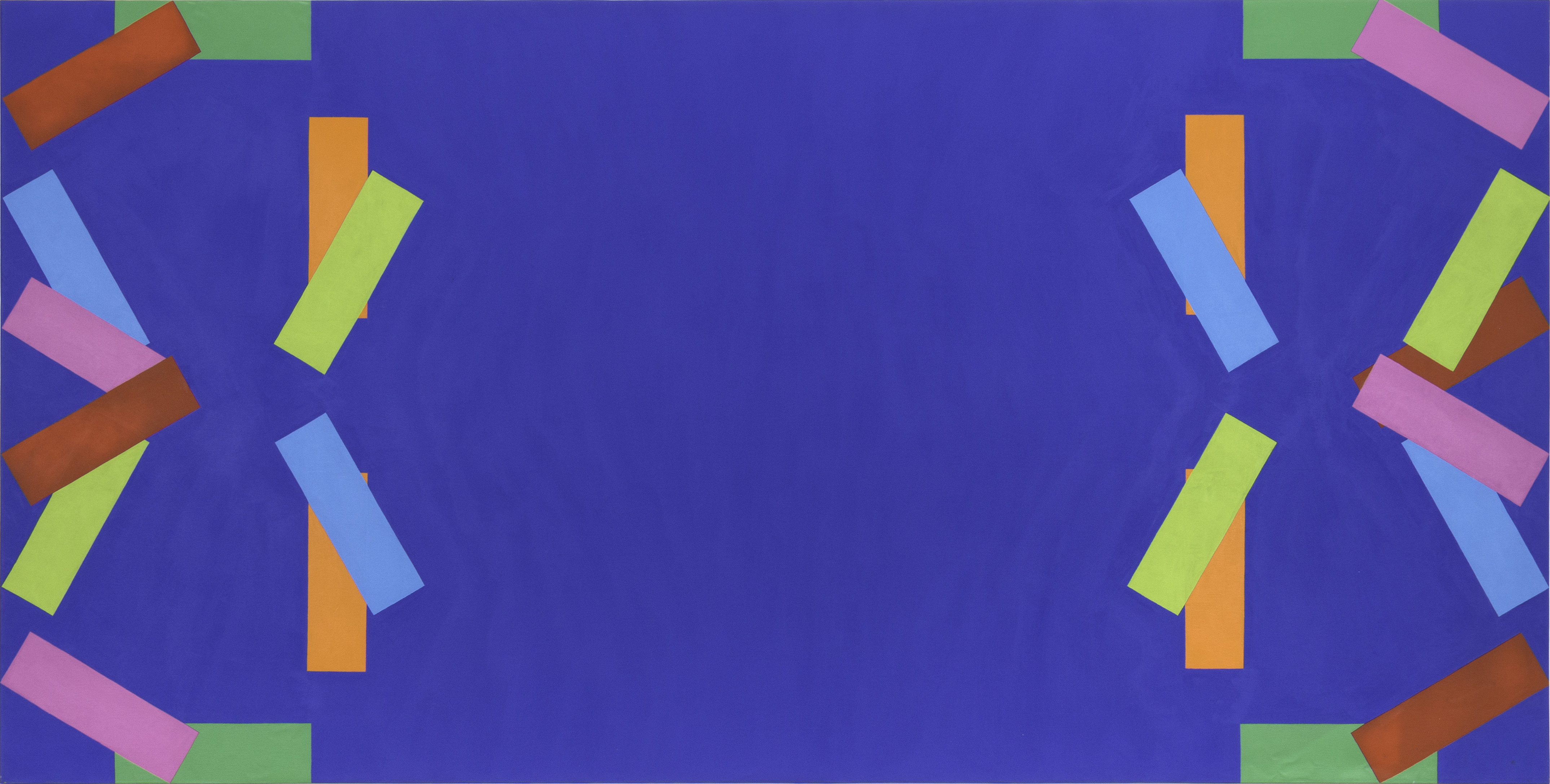

Rosemarie Castoro, Blue Red Gold Pink Green Yellow Y Bar, 1965

“For the men, their gender was invisible, for the women it was not. Their gender was never invisible”

While none of them self-defined at the time as feminist artists, they nevertheless faced barriers as women making work. “Even though these artists dedicated themselves to extreme rational, mathematical concepts, they received the same social reception as women. It didn’t change with the gender neutral concerns of the work,” Kempkes explains. “They always had to go the extra mile. Always one step further. Their position within the avant garde was not a given, and so the work is so experimental, so remarkable. It’s expanded the form.”

It is a challenge that persists today, even as steps are taken to redress the balance. Tate has taken an increasingly active stance, acquiring many female artists for its permanent collection in the last year, while the Met Breuer has dedicated the majority of its solo shows to women since opening in 2016. For Wanda Czelkowska, Rosemarie Castoro and Lydia Okumura, though, they had to fight to have their voice heard, and it is only now that their work is gaining greater international recognition. “They were coming from a different perspective in society. For the men, their gender was invisible, for the women it was not. Their gender was never invisible.”

All images courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, Paris, Salzburg and Anke Kempkes Art Advisory. All portraits copyright the artists or the artist’s estate.

Land of Lads, Lands of Lashes: Rosemarie Castoro, Wanda Czelkowska, Lydia Okumura

Until 11 August at Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery London