In this column, A Little Mission, Tosia Leniarska follows artists into places of intrigue or personal significance to talk about their work. This month brought her to an abandoned village and a town hall in the southeastern Arabian Desert, its portion in the Sharjah Emirate stretching between Dubai and the Omani border. She spoke to artists Raven Chacon and Luke Willis Thompson, who chose these sites to show their works as part of Sharjah Biennial 16: “to carry.” They attended during March Meeting, the historically iconic regional gathering of artist talks and performances – this time, during Ramadan, held at night.

All places in the world are loaded in one way or another, yet some thick ley lines of world capital, glamour and political division intersect here, at the bedazzled UAE airport where I arrive. I disembark my flight with an open heart – the headpieces of Emirati Airlines hostesses freshly pinned to my inner-life moodboard – but my mind is filled with in-flight reading of statistics on the country’s concentration of wealth, which is at the expense of the population’s almost 90% of immigrant workers with no share of public life. This is to say the extreme disparity is well concealed — much better than in a place like, say, the US, which is prouder in violence and quicker to kill spiritually upon arrival. And so, I arrive in Sharjah snooping around for gossip, the most reliable form of knowledge circulation in this context, to better understand the nuanced extremes.

My quick low-down is that Sharjah is a little suburban in comparison to Dubai; smaller, calmer, and slightly folkloric – an aspect which I am quickly told will be enhanced for my gaze as a Westerner from the art world, and press at that. Many of the historic buildings in Sharjah were preserved by the current Sheikh – some traditional, like the 19th-century fort, and some 1970s ones that, to my Eastern European eye, were a fun Soviet-esque reminder of the Non-Aligned Movement, via The Flying Saucer. The Sheikh’s daughter is the Sharjah Art Foundation’s director and the curator of the Biennial’s previous edition, Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi – who stands alongside her siblings and cousins presiding over various foundations, as royals do.

The Sheikh is a public intellectual credited with establishing Sharjah’s standing as the region’s cultural centre. I get the sense of a general anxiety that the approach of his death, imminent as it is for us all, may undercut the generous funding for the arts. It seems uncertain that the successor shall be as enthusiastic about contemporary art, and so the spring that gave rise to the Biennial’s success might soon dry up. I also hear that the Sharjah Emirate is “dry” not because of the Sharia law but also, reportedly, as a result of tragic royal misconduct – so for drinks, we head ten minutes down the road to Ajman.

The Biennial is so huge – spread geographically across the Emirate and conceptually across five curators – that I’m reluctant to think that an attempt at a generalised overview will be appropriate. Try to identify the common threads and you will arrive at the simultaneous need to address politics and the impossibility of political coherence in an exhibition setting. This trouble is approached by the exhibiting artists with various levels of self-awareness, grief, acceptance, or desperation – more or less convincingly amid the flailing liberal world order. But the two artworks I want to tell you about faced this deadlock, with questions, without answers, and found their way through – and I felt like I followed along on and out of reductionist traps.

On the way to the site of Luke Willis Thompson’s video work, he tells me it’s essentially a sci-fi movie – one he initially envisioned as a TV series. I soon find out this is a pretty misleading description. Across the many sites of the Biennial dispersed across the Emirate, the one Thompson picked for his work is an old town hall, one of the historic buildings preserved as exhibition spaces. It has a bureaucratic feel to it; here is where people met for decades to vote on minuscule changes in their governance. I imagine raised hands, ballots, notice boards. This is why he selected this place, he explains – to watch the film where people construct and legalise their political reality.

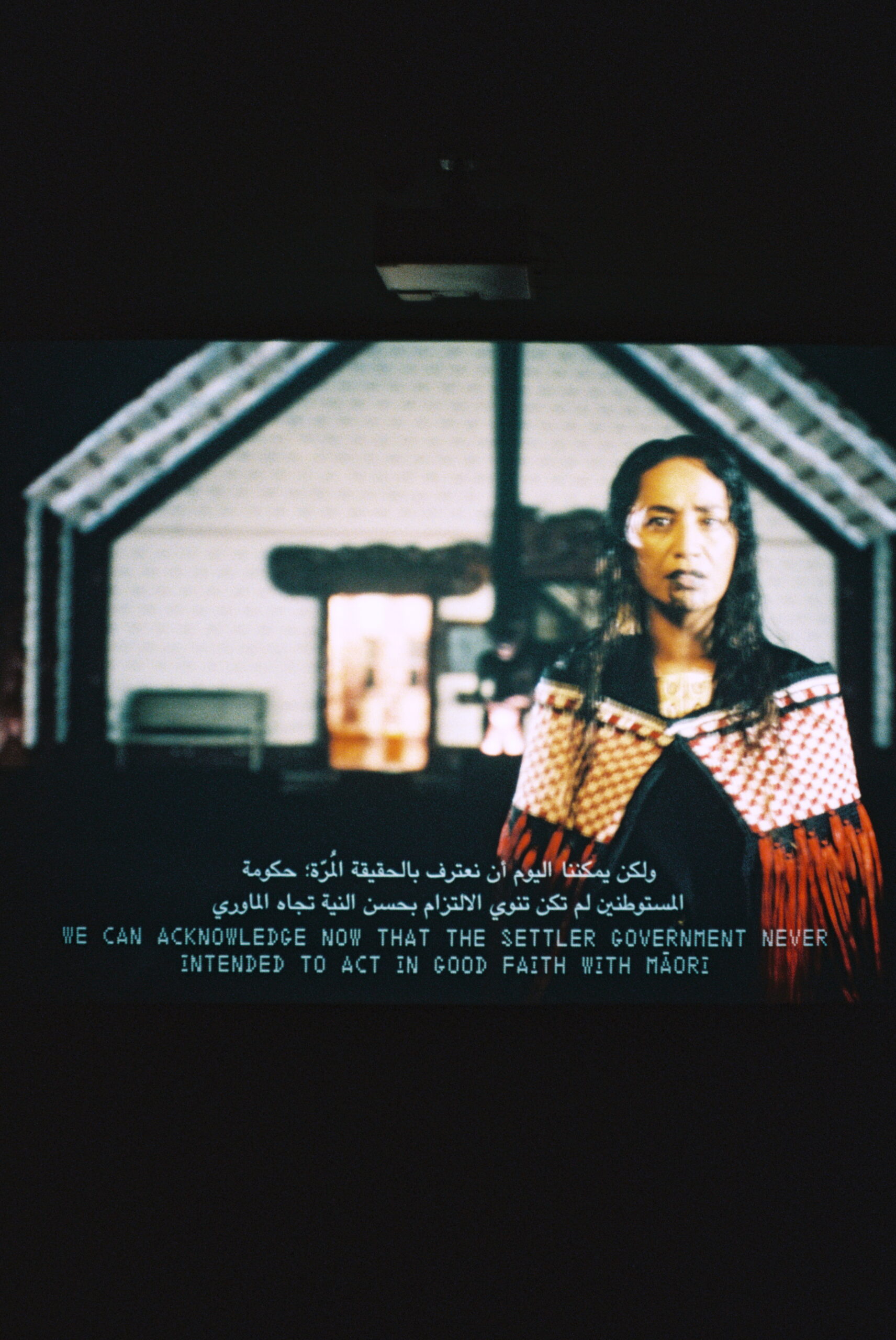

The film’s title, Whakamoemoeā (2024), translates to “dreamy” or “to cause to dream” in Māori. It’s a twenty-minute recording of a political speech delivered to the camera by Oriini Kaipara, a woman who, I’m told, became a celebrity in New Zealand for being the first mainstream TV news anchor with a moko kauae – a Māori woman’s facial tattoo. She delivers the impassioned monologue in Te reo Māori with English subtitles. Based on Thompson’s description of the project as a science-fiction TV broadcast, I expected it to be part pastiche – for Kaipara to stylise her performance, to play into newsroom aesthetics or propaganda kitsch. But this is not that kind of fiction. The tone is serious, and the only immediate signifier of futurism is the date, February 6 2040, in a Matrix-style font on the title card. Two hundred years before the film’s date, the 6th of February 1840, was the day the British Crown and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi, the formative colonial document of New Zealand. On the 200th anniversary of the Treaty, we witness the formation of a new Māori state – and we are watching the TV broadcast of its announcement.

In writing the speech, Thompson collaborated with Māori political theorists and elders to pick the route of genuine immersion – that is, what a chief would actually say as a politician in this scenario. No pastiche, no irony, no hyperbole. The fictional leader would be speaking to the Māori, not to other New Zealanders. They would perform an official lament for what it took to get there, like a Western politician performs a moment of silence, name the laws that prohibited them from achieving this before, and address the practicalities of the newly formed state. Are they keeping the parliament? The city hall? Who becomes a citizen? The script is entirely committed to this logic, and it reads real: the English translation mimics what I know a political speech to sound like, while the genuinely mournful lament remains untranslated – the subtitles are simultaneously boring, like an 1840s treaty, and gripping like pain.

The plurinational structure proposed in the speech is based on a real proposition put forth by a group of Māori political theorists. It’s a legal dream. The lines between speculation and utopia are blurred; if you want to start a revolution, here is the research paper to base your manifesto on. The subtitles of the film include a litany of names of Indigenous activists in a genuine, untrendy doubling down on didacticism: Thompson wants it to be a film that can be shown in schools and for students to Google the names. The dry and cold camera eye leaves me self-aware in front of it: it’s a clear, unbeguiling proposition. And while I certainly learned a lot from my Googling, I feel most confronted by the contrast of the work’s total directness set against Thompson’s total ambivalence about it being taken literally.

The oblique angle I received from the artist’s introduction – that the work is sci-fi, that it’s like TV – opens up the work’s undercurrent of irreverence. What do we take seriously? Are we imagining this future at an exhibition because we don’t actually want it to happen? What would it mean to commit? These questions are difficult to ask – especially now, as many status quos dissolve, and there seems to be confusion in telling apart which are symbolic and which are material. Whose future is getting nulled, and whose was never really taken seriously to begin with? Can the symbolic support of institutions for Indigenous sovereignty ever be translated into a political reality? What would that take? What would we write in that legal treaty? Who gets hurt? Thompson tells me the questioning is scary, not cosy. To read it as a utopian vision, rather than a challenge to utopianism, would be to overlook large chunks of reality. But reality can be overlooked, it is overlooked every day, some get to overlook it more than others. The work is speculative fiction, too. Thompson speaks with discomfort about people seeing the work as a beautiful statement: it’s unclear whether he believes the vision is what should be realised, beyond what should be imagined. Perhaps what he believes in is the cause of imagining legislation – of making dreams legally specific.

Interested in specificity, I tried to source gossip on what it meant for the Biennial artists to develop their commissions in the context of Emirati funding structures. Money has its strings attached in any country, and it’s worth knowing about the compromises made; for one, I know almost none of the works here could be commissioned by German institutions now, given its new enthusiasm for censorship in the context of genocide. Thompson responds to my question with clarity: his is a separationist work. He could never have had it funded by the government of his citizenship. Perhaps this is true. But, of course, Indigenous people have a particular positionality as citizens; whichever state it is that controls their unceded land, their positions are, likely, inherently at odds with the governing body. So, Thompson asks me: “Where else if not here?”

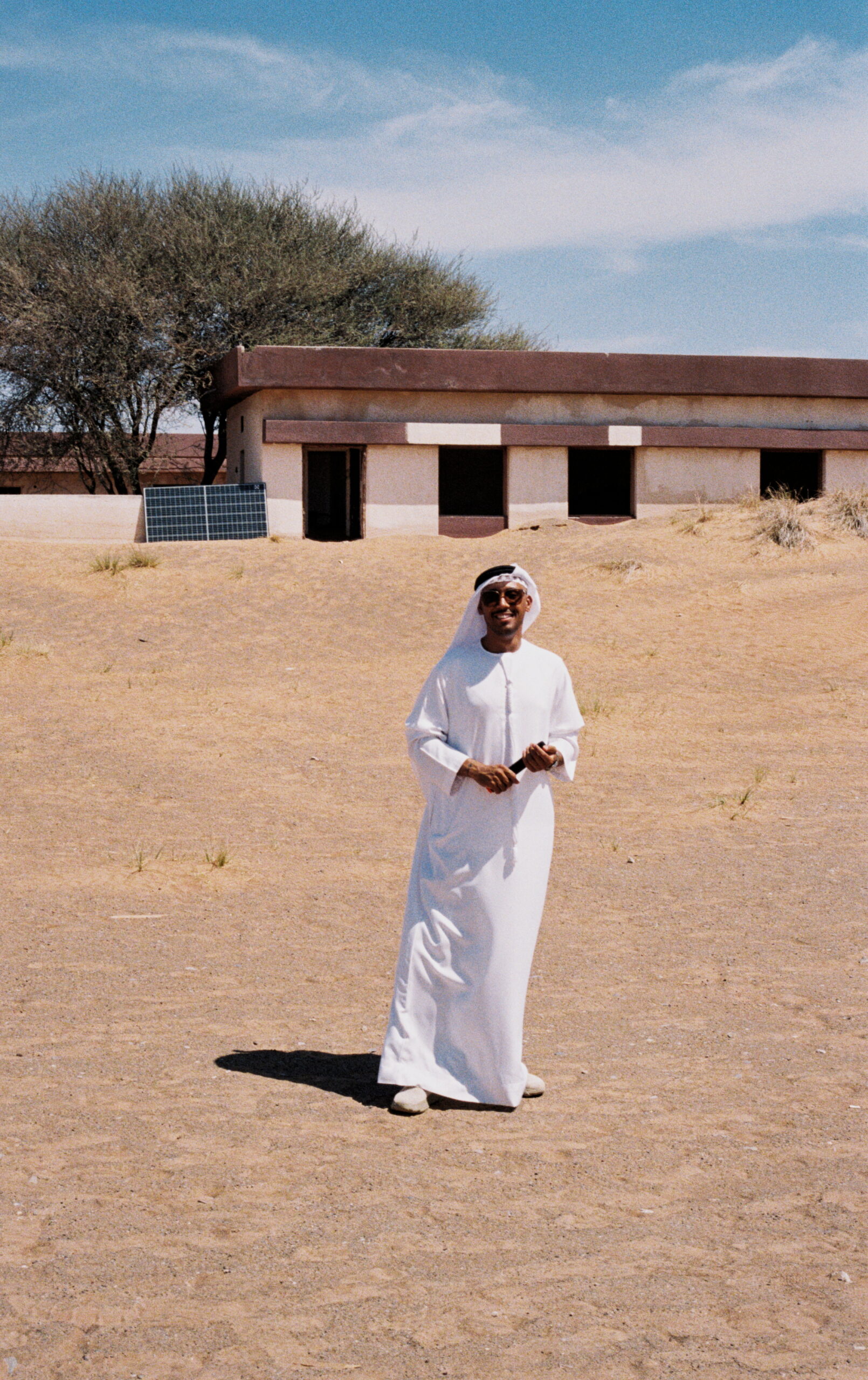

We’re driven to the desert, led by Omar, the Sharjah Art Foundation’s charming tour guide with an air I’d describe as cunty if I could. He shepherds us from the blazing sun to beneath the one shade-giving tree in the “Ghost Village” of Al Madam, a scattering of concrete houses and a mosque sunken into the desert sand. I’m here to listen to Raven Chacon. The artist, composer, and noise musician from the Navajo Nation has a Pulitzer Prize for Music alongside a prolific conceptual art practice – both solo and as part of the groundbreaking Indigenous art collective Postcommodity, which he left in 2018. I’m a fan; the recent Pulitzer win was for his sort-of meta Christian mass composition, written like a Trojan horse to be performed in churches as a Thanksgiving commission. Standing underneath our desert tree, wearing an industrial noise band t-shirt, he speaks with the cadence of a friendly uncle.

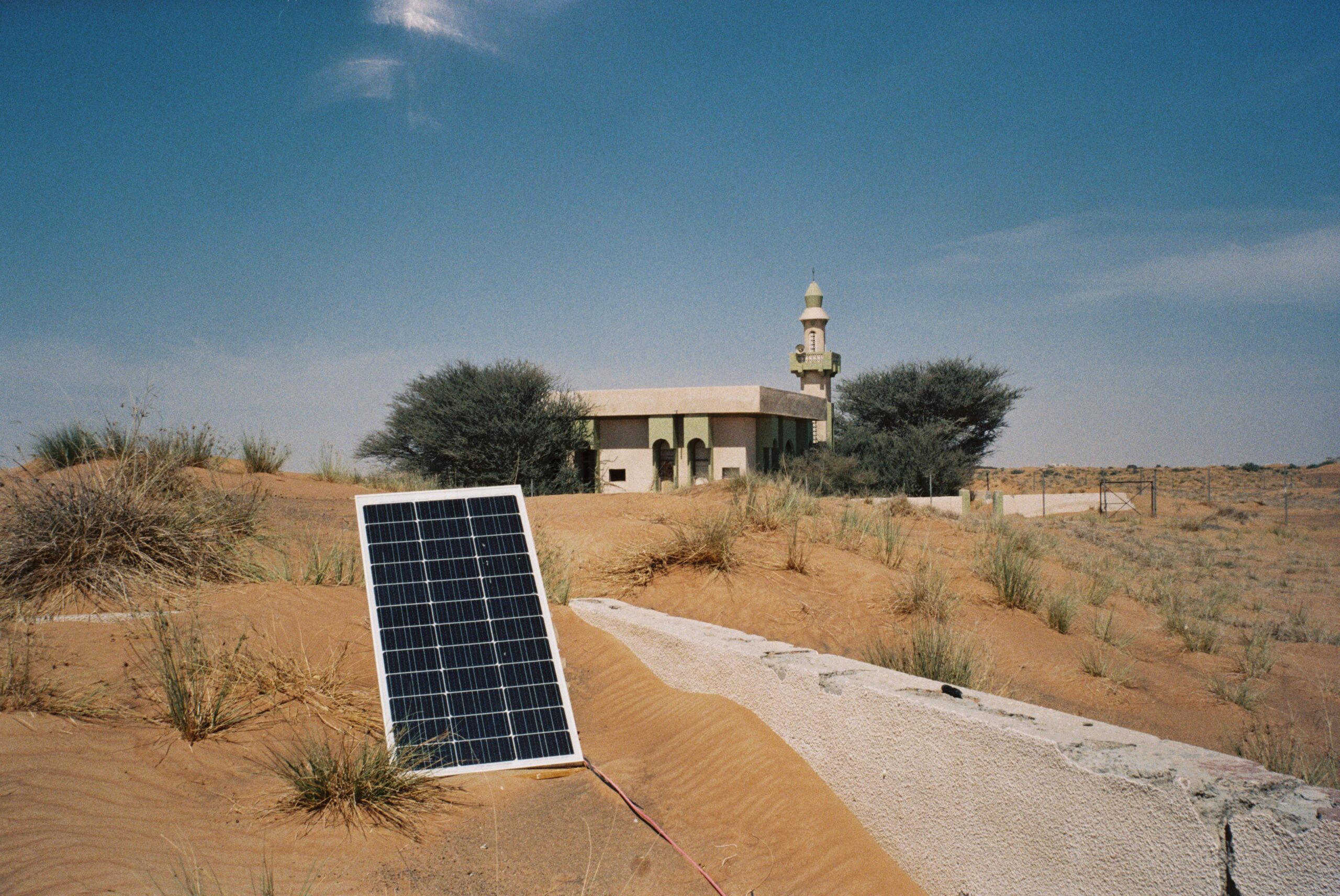

Chacon’s remote commission, A Wandering Breeze (2025), runs on solar generators: it consists of multiple speakers interspersed through the village and its surrounding desert. Skipping between each speaker are two traditional Bedouin desert songs performed by a local group of musicians who recorded them with Chacon. The listening experience is dislocating yet linear. The music is lyrical, familiar, but it ignores your presence as a listener and moves across the village faster than you could follow it. Its continuity is performed at a more-than-human scale – the chanting skips over the listener and off into the distance until finally reaching the speaker farthest removed into the dunes, from where it sounds like an echo of people who have long left. The songs are wistful. Chacon explains that the lyrics follow traditional formats of describing nomadic life – its loneliness and nostalgia of freedom, the relationship that emerges with the desert – the sound moving freely, the people moving freely.

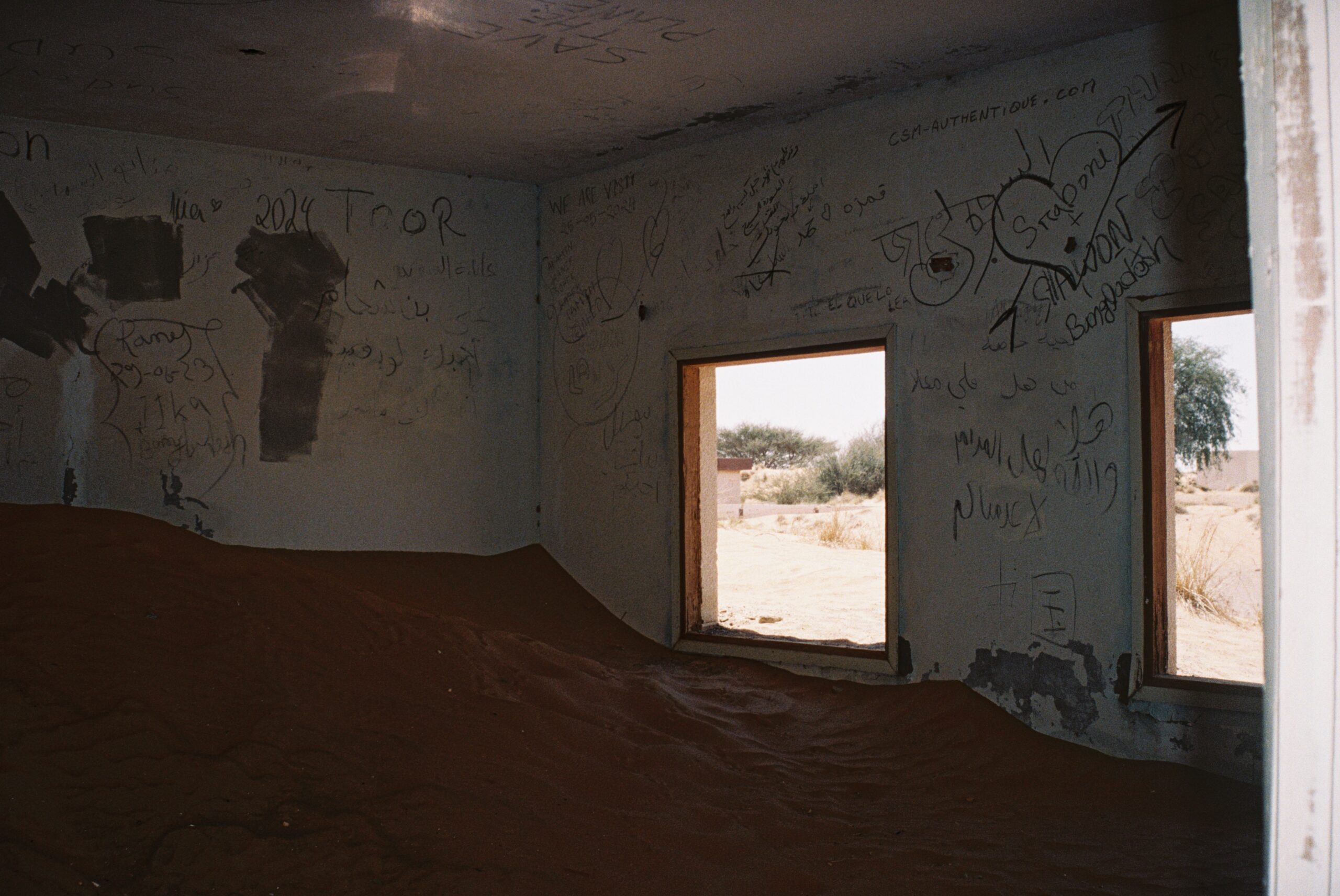

I feel quite moved by the effort put into hiding the speakers from me, like a child in the theatre, happy to be immersed. And like a child, they make me anxious about being left behind if I trail too far out: Al Madam was never inhabitable. To describe the village, Chacon avoids the terms ‘buried’ or ‘ghost’ – because they imply death, while the people forced to inhabit it have survived. Al Madam was built by the Emirati state during its unification in the 1970s, in an attempt to house – or to contain – the indigenous tribe of nomadic Bedouin people. It could never have worked: without consultation, it was built in an inhospitable place that no one would have chosen to settle in, with architecture unsuited to the natural conditions, taking no heed of the thousands of years of people quite literally figuring it out very well for themselves. No one could be convinced to stay; the buildings were soon swallowed by the dunes.

In Chacon’s turn of phrase, this was a case of ‘forced placement’ rather than ‘displacement’ – one that he recognises immediately from his own context: the forced settlements of the Navajo people in the US’s Southwest. In choosing their places of settlement, Chacon says, nomadic people follow the animals, never staying somewhere not even the animals would. But prices of land and real estate dictate other ways of mapping; the government will move people to the middle of nowhere and call it social housing. (In another architectural analogy to Eastern Europe, I recognise this in hostels for refugees that have opened in abandoned Soviet-era hotels deep in remote forests.) Like in Thompson’s film where he centres the voice of a Māori speaker and the script of Māori writers, Chacon chooses not to write his own composition – distancing himself from the Bedouin songs, he makes space for their mutual echo to resonate.

On our drive back, I Google the village of Al Madam and am surprised to discover that visitors who have written about it seem not to know why it was abandoned – some describe it as ‘a mysterious reason’. I’m not only referring to tourists who could be presumed ignorant, easy to condescend, but also local friends who I would have expected to know this history. Perhaps the projects of resettling the Bedouin are not or were not public knowledge. In an oblique turn, this history seemingly needed a Navajo artist to come in with his parallel and create work that clarifies it in public, making sense of one place with the empathy of another.

I ask Chacon about his impression of the musicians he worked with, and what their feelings are about how the government treats them now. He explains that they are paid from a government heritage fund just to create songs, in order to maintain their musical traditions – and emphasises this is something quite special in itself. Given the circumstances, he warns that he wouldn’t expect them to be comfortable with sharing any criticisms. Later, however, I learn through my gossiping companions that the government runs extensive programmes to pay Bedouins to live in the desert, outside the urban society, as long as they remain loyal to the Emirati state. One motivation for this, I’m told, is to preclude them from siding with military groups that might offer financial incentives. What legal treaties could be penned for this? I begin to wonder, and have no resolve right now, what similar practices might exist for Indigenous communities elsewhere, and whether such an approach could ever be considered a desirable solution in other contexts. Yet the fact that such comparison even arises seems like something that could only happen here.

In his talk during the evening March Meetings, Chacon talked about the musical concept of transposition – of translating a musical idea from one form to another, without changing its qualities. How do you play the same piece on a different scale? What makes it remain the same? Do you preserve the affect or the intervals between notes? Throughout the Biennial and each evening talk, translation resurfaced again and again as both a gnawing responsibility and a chance for liberation. It raised the question: should you meet people where they are, even if it means compromising your clarity, or stay committed to the one sense you were after? The real substance lies in (of course) both, and in neither, and especially at the same time. It doesn’t work otherwise. Many things are desperate to be true at once: to hold them all is a noble effort, perhaps doomed, but the only one worth making.

Written by Tosia Leniarska