Stephanie Comilang, a Filipino-Canadian artist and filmmaker based between Toronto and Berlin, deftly weaves together stories, histories, and memories in her latest exhibition, “Search for Life,” presented by TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary and curated by Chus Martínez. This show marks the artists’ debut solo exhibition in Spain. In her work, Comilang navigates time, space, and technology, envisioning a future shaped by interconnectedness and innovation, delving into the complexities of displacement, transition, and labour in a globalised world.

The exhibition features a large-scale film and textile installation, through which Comilang unpacks colonial legacies, diasporic realities, and ecological interconnections that define our contemporary landscape. Drawing inspiration from a book titled “Diaspora ad Astra,” which explores the theme of people stranded in spaceships, Comilang was struck by the similar plight of Filipino seafarers stranded during the pandemic. Collaborating with her father, she crafted a film that interweaves personal anecdotes, footage from the Philippines, and a soundtrack evoking themes of longing and separation.

Simultaneously, we’re drawn into the journey of monarch butterflies, mirroring the migratory patterns of Filipino seafarers navigating global shipping routes. Here, the parallel is striking, highlighting the vital role of these seafarers in sustaining the flow of global commerce. The film blends narratives that bridge the gap between past and future, addressing themes such as dispersion, lineage, perseverance, conflict, and longing, alternating between documentary and science-fiction.

The film, displayed on a large digital screen, traces the maritime routes used by Spanish conquistadors after the colonisation of the Philippines. Central to the narrative is the butterfly, serving as a symbol of transformation and resilience. Through its flight, we encounter a diverse cast of characters – a painter, a florist, a scientist, an academic, and a former seaman – each offering a unique perspective on the enduring impact of Spanish colonialism on Filipino heritage. Amidst these reflections on identity and memory, the colour orange emerges as a symbol of hope amidst adversity, echoing the life-saving devices and visibility crucial to navigating turbulent waters. The narrative also explores themes of identity and home, drawing parallels between the migratory instincts of butterflies and the experiences of immigrants navigating unfamiliar territories.

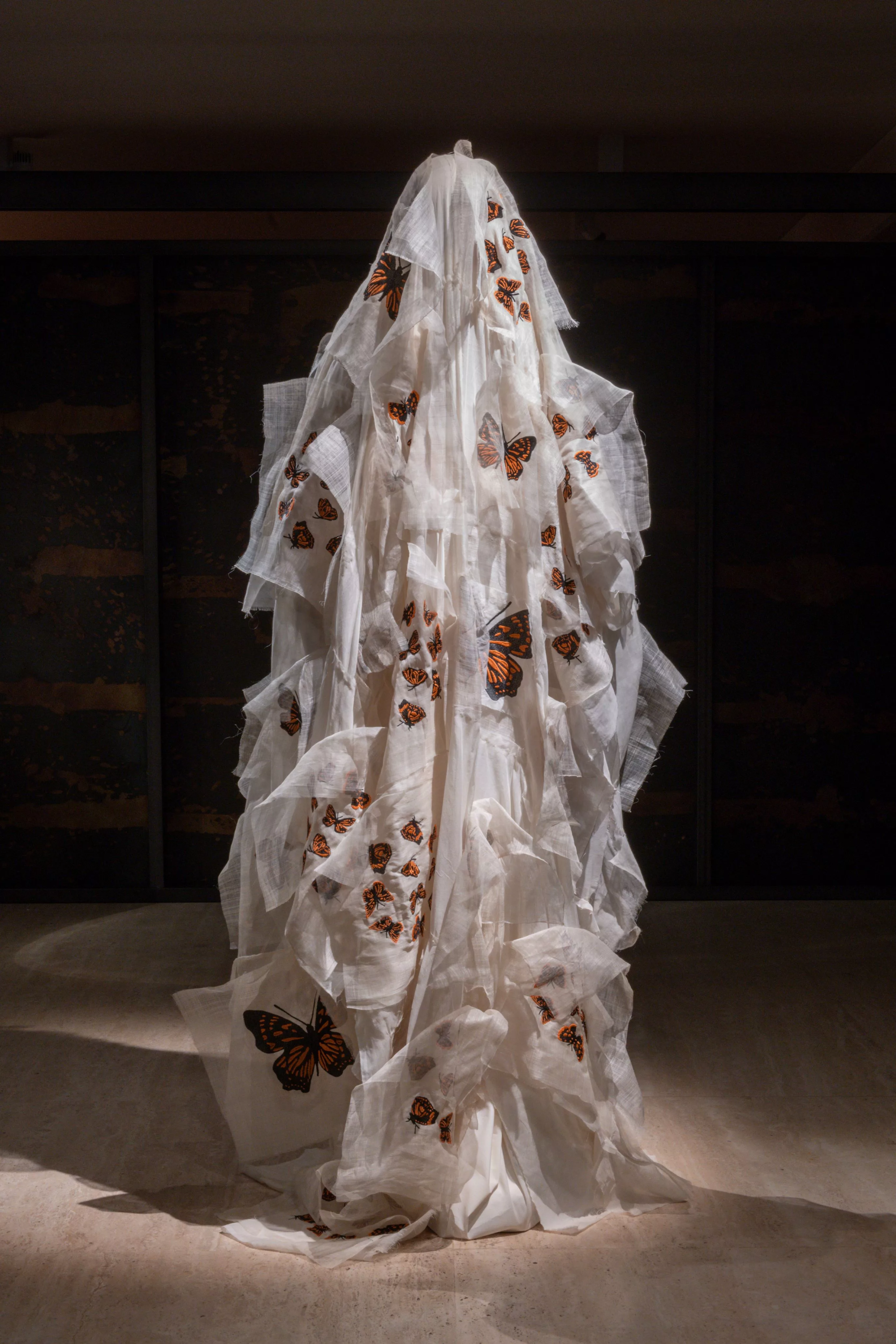

Complementing the film are textile creations made of pineapple fibre, with images referencing Manila shawls and the Spanish colonial past. The cloth, embroidered with monarch butterflies, is draped over two figures which stand at each end of the space, mirroring the symmetry of butterfly wings. The works speak to colonial trade routes, juxtaposing historical accounts with contemporary realities. References to Chinese weavers, Spanish colonial relations, and the Manila trade route paint a vivid picture of the complex interplay between cultures and economies.

“Search for Life” is a reflection on history, identity, and the interconnectedness of human and non-human life. Comilang invites viewers to contemplate the complexities of our shared existence and the potential for positive change in our relationship with the planet and its inhabitants. Comilang’s personal journey, inspired by a dream of opening an exhibition of butterfly paintings, adds a layer of depth to the narrative. Through her research on monarch butterflies and their metamorphosis, she grapples with questions of identity and transformation, shedding light on the enduring impact of colonialism and the imperative to confront present-day injustices.

Ultimately, the narrative serves as a poignant reminder that colonialism is not a relic of the past but an ongoing reality, intertwined with contemporary struggles for justice and equality. Through storytelling and art, Comilang seeks to raise awareness and foster dialogue, connecting with audiences on a personal level and inspiring action towards a more equitable future.

Elephant speaks to Stephanie to uncover more of the stories behind “Search for Life” and explore the layers of meaning woven throughout the exhibition.

- What initially drew you to exploring the intersection of visual art and filmmaking? How do you navigate between different mediums, such as video installation, sculpture, and embroidery, in your artistic practice?

I think moving into different artistic mediums is starting to make more sense for me as I go along. Initially, I was focused on finding ways to expand my practice. At first, I was solely creating film and video, but then I transitioned into installation art, and now I’m exploring sculpture and textile work as well. For me, if a new medium aligns with the narrative I want to convey, it becomes a way to broaden the avenues through which I communicate.

I do think extensively about materials, and although I may not possess the same level of expertise as artists who have been working in these mediums for years, I really contemplate the significance of the materials I work with. Take, for example, the Pina fabric made from pineapple fibres, which originates from the Philippines. While pineapples themselves aren’t exclusive to the Philippines, I delve into the journey of how they arrived there, their cultural significance, and their historical ties, including the impact of Spanish colonisation. These are the considerations that I take into consideration as I explore different materials and their stories in my work.

2. Was there a particular film or documentary that first drew you to working in this medium?

You know, growing up, I didn’t see many Filipino female contemporary artists or filmmakers who I could really relate to or look up to as a role model. There was one filmmaker, though, a Filipino named Kidlat Tahimik, often called the Godfather of experimental cinema in the Philippines. He made a film called “Perfumed Nightmare.” I came across it when I was a teenager because my dad had a VHS copy. It turned out that my dad and Kidlat Tahimik actually went to school together and were friends.

Watching “Perfumed Nightmare,” I felt a connection, even though I was born in Canada to immigrant parents and he lived in the Philippines. There was something about his work that resonated with me, something I could relate to despite our different backgrounds.

3. Can you discuss your approach to storytelling in your artwork, particularly in blending speculative and historical narratives?

Objects often contain numerous stories within them. You could pick almost anything and delve into its history, finding connections to various people, events, and narratives. In this recent project at TBA in Madrid, for instance, the butterfly served as a central motif weaving together multiple stories. In other works, it’s been the pineapple or even a drone, which takes on a character-like role.

I often seek out objects or elements from the world that have rich and multifaceted histories. These items become more than just props; they serve as placeholders for the narratives I want to explore. It’s through these objects that the stories come to life, intertwining and expanding beyond their initial contexts.

4. Much of your work incorporates elements of science fiction and documentary. How do these genres intersect in your work, and what role do they play in shaping the viewer’s understanding of migration and the diaspora?

At first, I was really into documentary filmmaking as a way to tell stories. I even made one, but I found it quite tough. It didn’t feel complete to me because I struggled with the idea of presenting one single truth. I don’t believe there’s just one truth out there. So, when it comes to art and filmmaking, I think blending different genres together makes for a more intriguing narrative.

I find mixing speculative or science fiction elements with nonfiction really interesting. I think all artists do this to some extent because we draw from our own truths, our personal experiences. Introducing elements of imagination adds depth and richness to the story. So, even though science fiction and documentary might seem like opposites, they actually complement each other, creating a fuller picture.

5. Could you discuss the inspiration behind your exhibition Search for Life? What led you to combine narratives of Filipino seafarers with those of migratory butterflies and historical trade routes?

During the pandemic, when many seafarers found themselves stranded on their ships due to concerns about spreading the virus, I created a short video exploring their lives. These seafarers, a significant portion of whom are from the Philippines, were unable to return home because port authorities feared they might bring in the virus. It was a difficult time for them; they could see their homes but couldn’t reach them. Amidst this, global shipping and trade slowed down, affecting our everyday lives in ways we often overlook.

Reflecting on the importance of these workers who deliver goods worldwide, I felt compelled to shed light on their experiences. When I was commissioned to create a video by Ocean Archive, an online platform for ocean-related content, I seized the opportunity. The resulting short film, “Diaspora ad Astra,” narrates the fictional perspective of one such seafarer stuck on a ship. He finds solace in a book titled “Diaspora ad Astra,” featuring Filipino science fiction stories, one of which mirrors his own situation.

The film tells the story of a man dreaming of fame but finding himself working on a ship instead. As he reads the book, he relates to the characters stuck on their spaceships, unable to return home. Narrated by my father, who often lends his voice to my projects, the film serves as an exploration of longing and displacement.

6. Can you describe your collaboration process, especially when working with individuals from migrant communities?

Typically, my filmmaking process doesn’t start with filming right away. Instead, I spend time immersing myself in the environment wherever I am. One example of this approach is shown in my 2017 film titled “Come to Me Paradise.” The film revolves around Filipina domestic workers in Hong Kong and adopts a unique blend of science fiction and documentary elements. It’s narrated from the perspective of a ghost, portrayed by a drone.

To find the women to feature in the film, I turned to YouTube. I wanted to incorporate vlog videos made by these women to provide a personal and diary-like glimpse into their daily lives. I stumbled upon a vlogger who had uploaded videos offering advice on various aspects of life as a domestic worker, such as financial stability tips, alongside content like cooking and makeup tutorials. I reached out to her through YouTube, and that’s how our collaboration began. Some of her videos ended up being included in the film.

While I utilised the drone as a character with an aerial view, I also made sure to fly it low to maintain a more intimate perspective. Additionally, the women I worked with filmed themselves using their phones, contributing to the film’s personal vlog-style aesthetic. This combination of drone footage and personal vlogs provided a multifaceted portrayal of their lives, blending different perspectives and storytelling techniques.

7. How did working in Madrid and at the Museum influence the message you wanted to portray in the exhibition? Did it inspire your overall practice in any way?

I wanted to give my work some context, considering it was made in Spain but also tied to Mexico and the Philippines. I focused on the Mantón Manila shawls with “Manila” in their name, as they symbolise a connection between these places. Upon researching their origins, I discovered their ties to colonial oppression, a common theme with many objects.

Regarding questions about my connection to Spain, I often find myself explaining that I don’t really have one. My strongest connections lie with Latin America, especially Mexico, due to historical ties – the Philippines was ruled by a Viceroy from Mexico. Interestingly, Spain might not view its former colonies in the same way as the colonies view Spain. While remnants like language and architecture persist, the effects of colonisation, such as economic instability, remain.

It’s surprising how little-known certain aspects of history are, even to Spaniards. For example, in the late 19th century, the Palacio de Cristal in Retiro Park housed a zoo that showcased not only crafts but also the Igorot people from the island of Luzon in the Philippines. This is a story that is often overlooked but deserves to be told, shedding light on the complex and sometimes uncomfortable realities of colonial history.

8. What role does research play in the development of your projects, and how do you balance fact with imagination?

For me, I often find myself fixated on particular themes or connections, like the relationship between the Philippines and Mexico or the experiences of Filipino seafarers. These ideas have been swirling in my head for years, and when I finally get the chance to bring them to life, they tend to come together organically. My process usually involves diving deep into research. I’ll visit relevant places, engage in conversations, and really listen to people’s stories. Then, I’ll step back, reflect, and decide what I want to capture on film.

It’s a back-and-forth journey of exploration, where I immerse myself in the subject matter, film what I feel, and then return to the drawing board to reassess. I don’t typically rely on scripts or predefined plans when I film; instead, I trust my instincts and capture what resonates with me in the moment.

As for research, I don’t often turn to books or archives but rather focus on understanding how technology can enhance my storytelling. For example, when I wanted to portray a character as a ghost, I explored using a drone as a versatile tool. I could manipulate it to achieve the effect I envisioned, adding a layer of intimacy that traditional filming couldn’t achieve. Similarly, I’ve experimented with digital embroidery machines to translate photography into textured artworks.

Ultimately, my approach revolves around leveraging tools, materials, and technology to convey my message effectively. I see myself primarily as a filmmaker, and my choice of cameras and innovative techniques reflects my desire to craft compelling narratives that resonate with audiences.

9. How do you see your work evolving over time, and are there any specific themes or techniques you’re currently exploring?

I’m really intrigued by the digital embroidery machine; I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of its potential. It’s fascinating to me because embroidery, traditionally seen as an ancient form of storytelling, is now intertwined with computers and technology. This juxtaposition between old and new, between the archaic and the modern, really interests me.

As for what I’m currently focused on, I’m still processing the Madrid show—it’s only been a few weeks since its opening. I’m continuing to explore the possibilities offered by the digital embroidery machine and how it can further enrich my artistic practice. It’s an ongoing journey of discovery and experimentation, and I’m excited to see where it takes me next.

10. Lastly, what do you hope audiences take away from Search for Life? What conversations or reflections do you aim to spark through your exploration of migration, diaspora, and labour?

Within the context of Madrid, I find it intriguing to observe how Spanish people, especially, might expand their understanding of the remnants of colonisation. It’s a significant aspect that often is not talked about enough. It struck me, during conversations in Madrid, how few people seemed aware of the historical significance behind structures like the Crystal Palace. It made me realise the lack of awareness surrounding colonial history and perhaps the need for a more nuanced understanding of it. This gap in knowledge prompts reflection on the broader implications of colonialism and its lasting effects on society.

Written by Rosie Fitters

Stephanie Comilang, ‘Search for Life’ Curated by Chus Martínez is currently on show from March 5 – May 26, 2024 at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

find out more