![Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze, The Divers II [Ada, a Pool, a Bike, Windows and Birds], 2021. Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/RA-041-image.png)

When it comes to the subject of the swimming pool in art, Hockney’s name still makes the biggest splash. As well as his iconic pop-art Splash paintings, works such as Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool (1966) reveal a fascination with the figure in water that encompasses everything from bathing Renaissance nymphs to drowning Pre-Raphaelite maidens. However, contemporary painters also continue to be captivated by themes of swimming and submergence, themes which are now being explored in a broad range of styles.

New York-based artist Katherine Bradford has been incorporating swimmers into her colourful, semi-abstract canvases for the past 10 years. “There are so many visual connections between how water looks and how paint goes on a canvas,” explains the 79-year-old artist. “The best and most mysterious effect is the transparency that inevitably happens when something is seen under water.”

“There are so many visual connections between how water looks and how paint goes on a canvas”

While Bradford’s approach chimes with what Hockney has referred to as an interest in the “formal problem to represent water”, her work is dreamlike, bordering on the cosmic. Some figures float in watery plains of colour, others appear to fly.

Of her upcoming show Night Swimming, which opens at Tomio Koyama Gallery in Tokyo in February, Bradford says: “Each painting takes good advantage of bodies immersed in darkness with just enough moon-like light to give our most daily activities a mystical and otherworldly glow. The beauty of light hitting the surface of water never fails to tempt me to put a swimmer in a pool of deep blue under stars and planets.”

Night swimmers also appear in Jonathan Wateridge’s recent luminous and languid paintings, two of which were included in the Hayward Gallery’s recent exhibition Mixing It Up: Painting Today. In these paintings, the pool is used as a “signifier of Western privilege or affluence”. As the artist explains, “I wanted to set up a self-contained and fabricated environment and to have the paintings portray a sense of that artificiality.”

It’s telling that Wateridge’s 2019 exhibition at TJ Boulting gallery was entitled This Side of Paradise, after F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1920 debut novel. The paintings summon up hedonistic Californian pool parties, but the atmosphere is sinister and unsettling.

“The beauty of light hitting the surface of water never fails to tempt me to put a swimmer in a pool of deep blue under stars and planets”

In art as in literature, water is rich in symbolism. Its meaning meanders from womb-like security to biblical rebirth, a sense of movement and change to foreboding and danger. “English is loaded with a rich swimming vocabulary that acts as a constant metaphor for how one might go through life, be it diving, floating, drowning, wading or surfing,” Bradford points out.

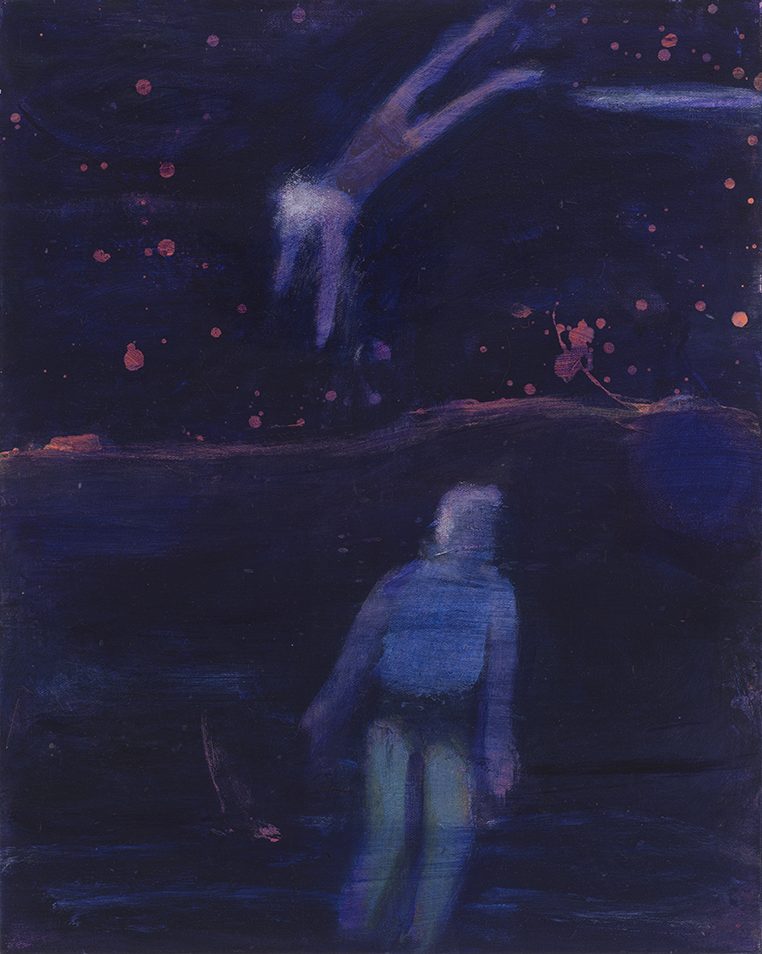

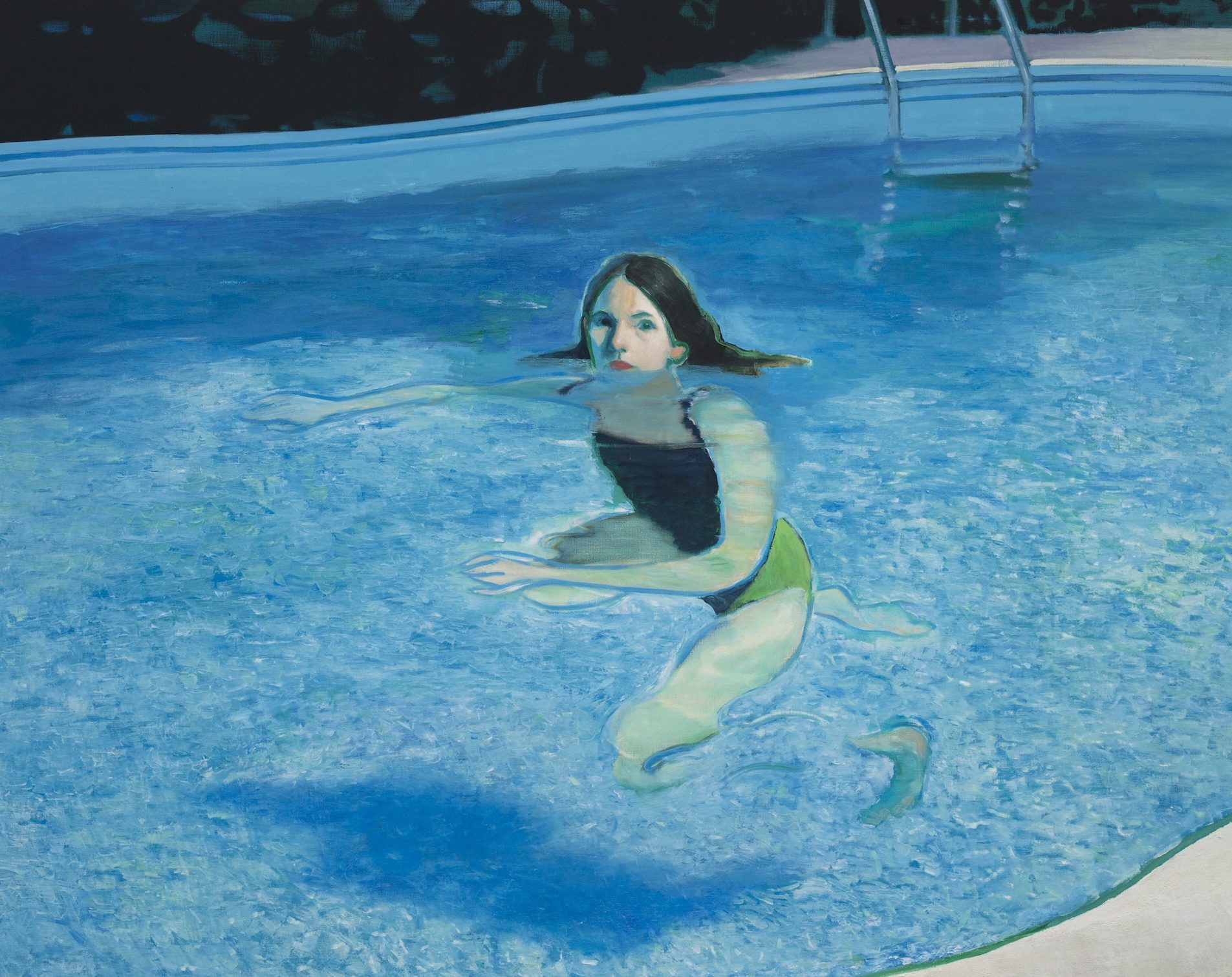

In the work of Nigerian-born, Philadelphia-based artist Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze, swimmers, divers and pools are part of a symbolic visual language that uses seven recurring motifs “as parts of a poem”, building collage-like compositions on paper. While her diving figures relate to a “continuous fixation with flying”, she says that the swimmers denote her desire “to be inside of water”.

![Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze, Pink Pool Ada Motorcycles [We Saved Ourselves] , 2021. Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/RA-040-image-scaled.jpg)

“I also find myself wondering about the undescribed depths of the water, its secrets and its dangers”

For Modupeola Fadugba, time spent in the pool is central to her practice. “Swimming is a meditative exercise for me,” says the self-taught Nigerian artist. “It’s my personal time to reflect, and meditate, to do the simple thing of breathing in and out, and remind myself that I’m alive. I first started using swimming as a metaphor for the artist, navigating the fluid and often turbulent space that is the art world.”

Fadugba’s ongoing Synchronised Swimmers

series shows bodies twisting and turning amid seductive watery surfaces, rippling, overlapping patterns of colourful pastels, burnt paper and gold leaf. Her time spent with the Harlem Honeys and Bears, a synchronised swimming team of senior citizens that offers free swimming lessons to local children, has also resulted in striking poolside portraits.

“Through my swim imagery I have been able to present a counter-narrative of the tragic stories we often hear about Black people and bodies of water,” Fadugba says, referring to research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US that states that drowning death rates for Black people are 1.5 times higher than the rates for white people. “With my work, I represent and amplify the triumphant stories, like those of the geriatric swimmers I worked with in Harlem.”

“I want to enter water like a space, a room, a world quite different than land. Land has always felt far too restrictive for me”

But while the pool can be political, it can also be intensely personal. In the work of LA-based British artist Tahnee Lonsdale, abstracted figures materialise from an undefined body of water, the tangle of semi-submerged limbs surfacing from her own emotional struggles. “I was going through a very painful breakup with a boyfriend while making these works, but the pain was mixed with the joy of finally getting my divorce from my husband, who I split up with three years previously,” she says of pieces such as Bath My Weary Limbs (2021) and Under The Shell (2021), where some figures seem to be sinking or drowning.

“Duplicitous,” is the adjective Lonsdale applies to water. “Submerged in the bath or the ocean, it provides gentle healing; you melt into the background. It’s a cure for anxiety and sadness. When you cry, tears are swallowed up by the water. Yet, it can also be a cold, dark place. Hostile and angry. Terrifying.”

The highly polished, almost too perfect paintings of London-based Will Martyr

have a similarly ambivalent attitude to H2O. They present a world of endless summer, where perfectly tanned and toned bodies lounge by luxurious infinity pools, with a heavy nod to Hockney in the glistening watery surfaces and idyllic villa settings. But Martyr highlights a distinction. “Hockney refers to the two-dimensional depiction of water, shimmering and moving,” he says. “While I agree, I also find myself wondering about the undescribed depths of the water, its secrets and its dangers.”

Perhaps even the sunniest of pool imagery asks the question “What lies lurking beneath the surface?”

is a London-based arts journalist who contributes regularly to the Financial Times and Evening Standard