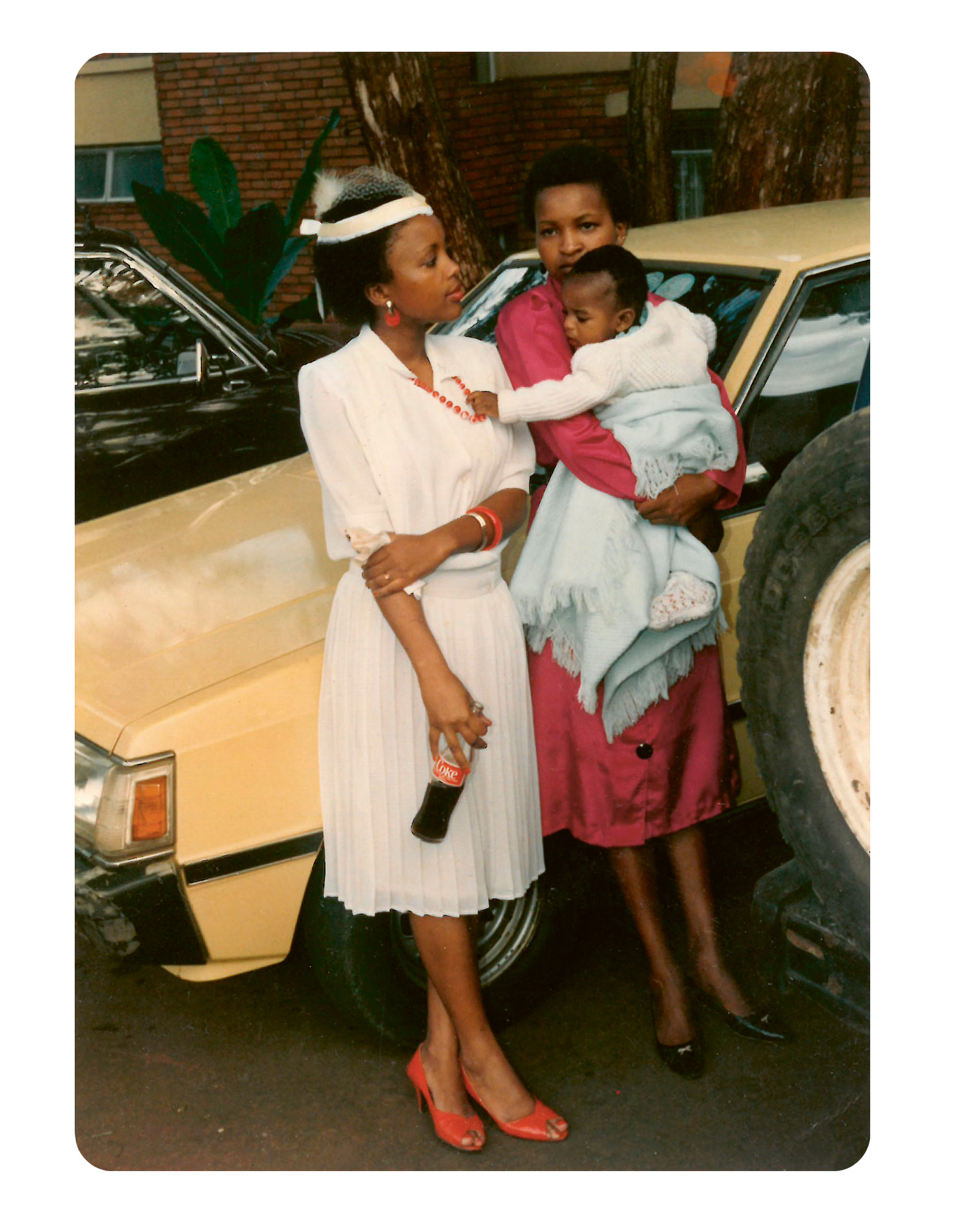

Vallerie Mwazo © Vallerie Mwazo

“Mothers are difficult to describe—or at least mine is”, the American novelist Edan Lepucki begins in her new book, released on April 7th, Mothers Before. Our mothers will always be our mothers—this role is what governs the way we perceive them within whatever family structure we have. But being a mother is only one part of the complex fabric of our identity.

Can we ever truly see our mothers as the women they were before us? When we look back at photographs of our mothers before they had us, we are unable to see them in their full complexity, with their own joy, pains, desires and experiences—separate to ours, wholly their own. When Roland Barthes describes weeping over a photograph of his own mother as a child, it has perhaps more to do with his own grief and sense of time than his mother as an individual.

“It is hard to believe my mother, or any of our mothers, really, had lives before they had us. How strange…” writes Vallerie Mwazo, one of the book’s contributors, whose words appear next to a picture of her mother in Kenya, dressed in an elegant white bottle, a bottle of Coca Cola swinging nonchalantly from her arm. It takes a child a lifetime to separate the strands of their own identity from their mothers—but we are all born, and no matter how different our experiences are from that point on, we are all connected via the matrilineal. This fundamental connection is what Lepucki asks us to explore.

Lepucki wanted to explore the ways in which female identity is shaped and shifted, by inviting a group of more than sixty women—mostly writers, poets, artists—to ruminate on portraits of their mothers before they were mothers. The brief was simple and broad: “Send me a photo of your mom and write about it in 100 to 800 words.” In a beautiful collection of intimate pictures pulled from family archives, these women (some of them also mothers themselves) also reflect, in deeply personal texts, on their mother’s lives. Together they create a revealing and profound insight into how identity is shaped by our mothers—that is sometimes surprising, and often subverts the stereotypical way we look at motherhood. “I hoped these micro-essays would capture not only a mother’s life, but a specific way to read that life, for we can’t disconnect these stories from their tellers.”

“When we look back at photographs of our mothers before they had us, we are unable to see them in their full complexity”

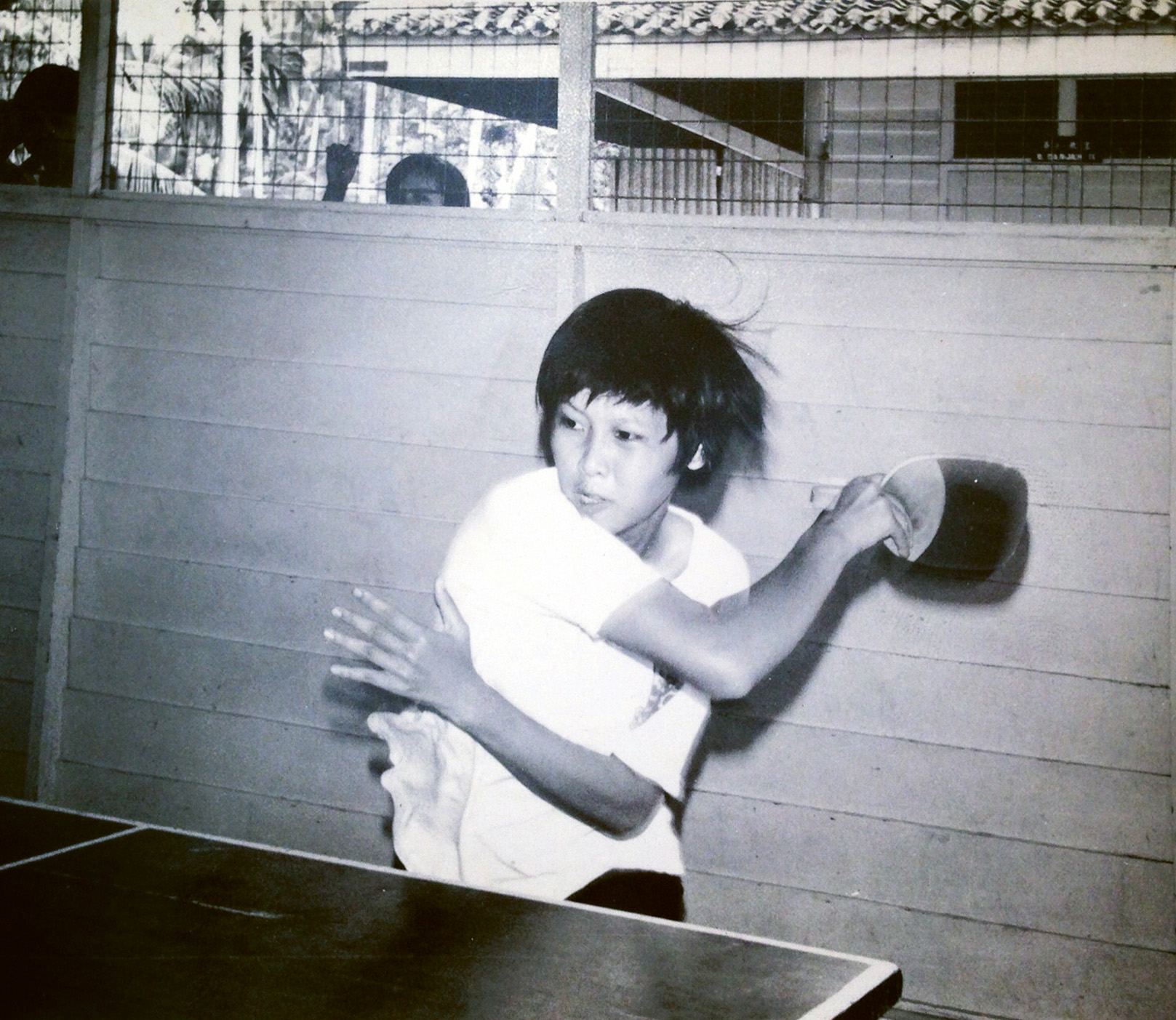

The novelist Rachel Khong is among Lepucki’s contributors. The picture of her mother immediately stands out among the many beautiful portraits, poised and posed. In the photograph, taken in the 1970s, Khong’s mother, Moi Ling, is captured mid-swing at a table tennis table. Her movement suggests she’s not an amateur—confirmed by Khong’s words, which reveal her mother was a skilled athlete, with a “mean smash.” For Khong, this photograph captures the essence of her mother’s approach to life—her charm “coupled with a determination bordering on stubbornness.” These were qualities that helped them when the family moved to the US from Malaysia. Through the picture, Khong also acknowledges their differences—something we all inevitably do, the beginning of our lifetime of comparing ourselves to other women. “As I child, I must have puzzled her”, she writes. What her mother thinks, however, we don’t know.

Alycia Elizabeth’s portraits of her parents before they had her give a glimpse meanwhile into another common thread in this narrative, placing matrilineal history at the very centre. Stories of migration, struggle, and self-determination are intrinsic to these accounts, and Elizabeth’s portrait of her mother is a moving reminder of women’s strength and perseverance, so often downplayed and neglected. She recalls how her mother—driven to the US in the wake of the Iran-Iraq war—a promising law student with her whole life ahead of her, has to adapt to a new life in a foreign country, working full-time, raising two children, cooking Persian meals for the family every night. “It’s no wonder that in many of my childhood memories, she’s tired and worried.”

“The renegotiation of a place for sexuality against the demands of mothering is an ongoing, but often hidden, pursuit of women.”

There are also plenty of portraits that speak of sexuality and femininity, something that is not often discussed in relation to motherhood. The beauty of many of these women, almost all of them captured still young and carefree, conforms to an ideal of conventional femininity. The subtle subtext of that, reflected in some of the texts, is a sense of loss, that is also an intrinsic part of the motherhood experience, the full submersion into a world of someone else’s ego that forces your own to move aside. The renegotiation of a place for sexuality against the demands of mothering is an ongoing, but often hidden, pursuit of women.

Lepucki has also set up an Instagram account in light of the book, inviting the public to share their pictures and stories. This ongoing online document shows just how diverse motherhood is: it is not only about women and children, but anyone who is able to fulfil the role of nurturing another with unconditional love. It’s about the way we are all defined by that fundamental relationship, whether it is easy, painful, or absent.

As Lepucki writes in her own text, motherhood is a contradictory and complex thing. “I want my children to have the privilege of taking me for granted. I want my efforts to be invisible to them—just as my mother’s were once to me. And yet, I also want to be seen for myself. I am a mother, and it’s a crucial part of my life and identity, but it’s not everything.” This is a valuable contribution to the contemporary discussion on motherhood, an enriching story that looks back, without shying away from the nostalgic and the sentimental, but that also looks beyond.

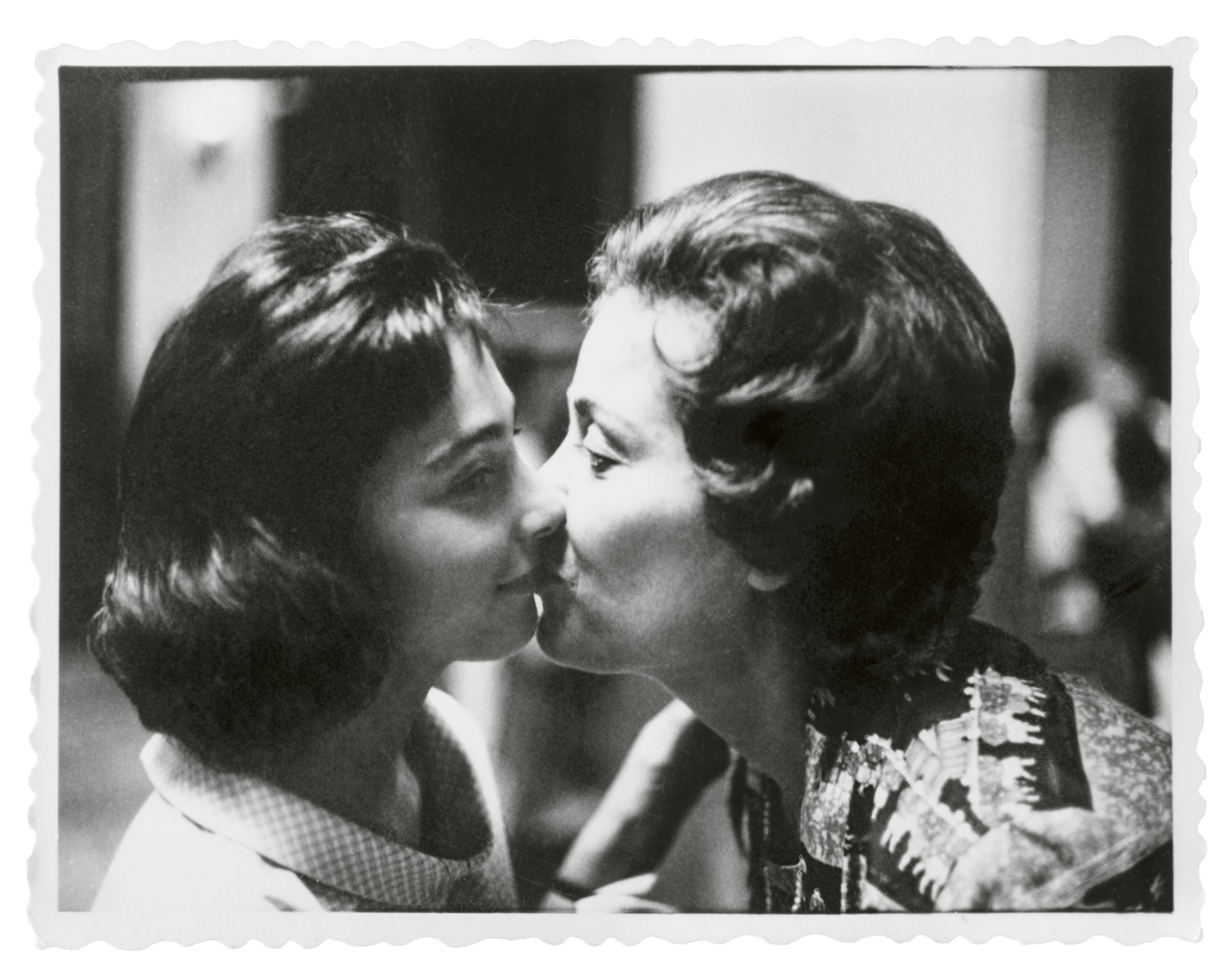

As the photographer Elinor Carucci writes, reflecting on a picture of her grandmother and her mother kissing—“a mother’s love is what makes this world bearable, possible. It’s what we will not and cannot survive without. In a world of cruelty and pain, there is this one miracle: mother’s love.”