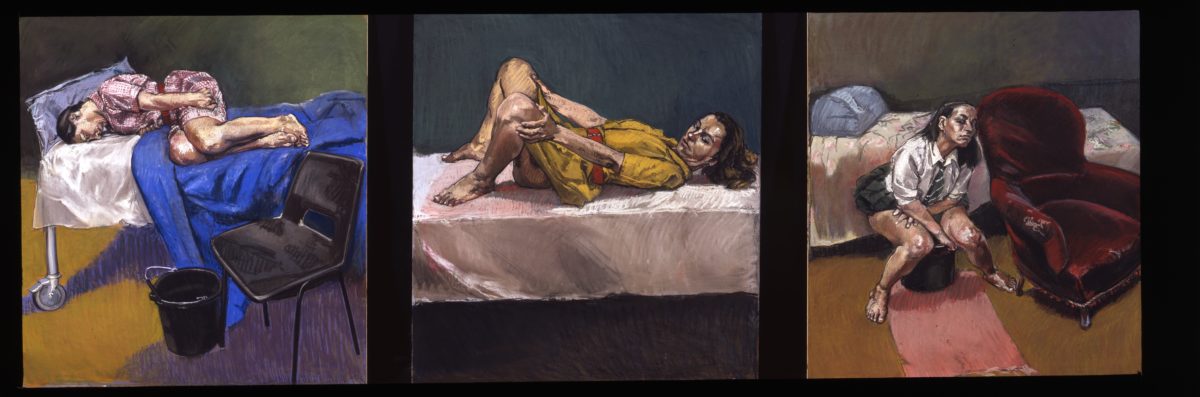

A young woman looks at you. Her jaw is clenched. A bandana the colour of blood pulls her hair back. Her hands clutch her thighs, holding her legs apart. Underneath the bed is a plastic bucket, and perched next to her is a bowl with a golden rim—the kind you might use to beat eggs into soft peaks.

Another woman doesn’t look at you. Her head is thrown back, jaw lifted skyward. Her midriff is exposed; her legs are bare and thrown apart. Glancing at her quickly, she could be in ecstasy. But her hands are clenched, and a watch lies face up on the floor next to a bundled sheet. Both these women are in the throes of abortions.

Paula Rego’s Abortion Pastels are powerful portrayals of a process that largely remains concealed and shrouded in stigma. Created in response to Portugal’s 1998 referendum on abortion (which, with a turnout of just 32%, maintained it was only allowed in exceptional cases, such as rape and extreme risk to the woman’s life), Rego’s portraits pull back the curtain on illegal abortions. She forces the viewer to bear witness to the “backstreet solutions” women are forced into when left with no alternative choice.

At the time, it was estimated up to 50,000 illegal abortions took place in Portugal each year, and Rego was enraged at what she saw as a denial of this reality. She could not bear the cruelty of policing and shaming women’s bodies.

Referring to her pastels as propaganda, Rego not only proclaims that abortion can no longer be ignored, but also challenges the limits of what art can depict. The pastels are devastating inversions of traditional reclining nudes, as the women who lie on soft furnishings with their legs spread are not erotic objects, but defiant subjects. Rego’s abortive women are wracked with pain, but remain stoic and strong. Sometimes they confront the viewer directly with steely, accusatory eyes. “Look,” Rego’s figures seem to say, “and don’t look away.”

Rego’s works are still shocking, largely because of their rarity. Although numerous visual artists have challenged dominant ideas about the body and female agency, there remains remarkably little art that confronts abortion explicitly. Tracey Emin has made a number of works referencing her two abortions, including How It Feels (1996)

, a harrowing early video work in which she recounts the botched abortion she had in 1990. In it she condemns the doctor who, after taking weeks to return her test results, told her it was too late to have a termination as he showed her a photo of his child and remarked what a wonderful mother she would make.

“Rego’s Abortion Pastels are powerful portrayals of a process that largely remains concealed and shrouded in stigma”

Unsurprisingly, the experience had a profound effect on Emin. Indeed, following her first abortion she suggested that she had “learned more about the essence and knowledge of where things come from than any fuckin’ art college or lecture or anyone could tell me.” Yet Emin remains atypical and, unlike Rego, refuses a political stance, describing her artworks as being neither pro-life or pro-choice. Abortion remains a taboo topic.

However, there are signs that this lack of visibility might be starting to change. In 2018, artist Barbara Zucker curated the exhibition Currents: Abortion at AIR, declaring abortion “as urgent a subject as any of the issues that now consume us.” Then, in early 2020, the two-part show Abortion Is Normal was mounted at two New York galleries. Organised in response to US state laws restricting abortion, the exhibition brought together the work of more than 50 artists (including Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger) to raise awareness and funding in support of accessible, safe and legal abortion.

Globally, three out of every 10 pregnancies ends in abortion each year according to the World Health Organisation, yet even the assertive title Abortion Is Normal suggests that there is still some way to go before this is widely accepted. Some artists, curator Jasmine Wahi admitted, “even chose not to participate because of the title.” The relative dearth of artworks portraying abortion only compounds the sense of shame that many women feel as they weigh up and undergo the procedure.

It is a conservative resilience that builds upon the dictum that abortions should be kept private, that they are not fit for the public realm. Almost half of the estimated 73.3 million abortions

taking place each year were conducted under unsafe conditions (in countries where abortion is illegal or highly restricted), with these unsafe abortions leading to as many as 13.2% of all maternal deaths around the world every year.

“Rego’s works are still shocking, largely because of their rarity. There remains remarkably little art that confronts abortion explicitly”

The need to confront the issue is as urgent now as it was when Rego created her series. Art can be a powerful tool: the impact of Rego’s series was so significant it has been credited with helping sway Portuguese public opinion towards a second, successful referendum in 2007.

Rego’s work was displayed at Tate Britain at an especially poignant time, as the UK government examined whether to make at-home abortions

a permanent option in England. Introduced temporarily during the pandemic, the measure allows those up to 10 weeks pregnant to receive the medical pills necessary for a termination in the post. It removes the need to travel to a clinic, making access easier for the most vulnerable in society.

As reproductive rights and women’s safety continue to be debated, it is an important moment to introduce the public to artists who create work demonstrating not only that abortion is both necessary and normal, but that it can even be celebrated.

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London