To really see a photograph, you may need to close your eyes (or so Roland Barthes suggested in Camera Lucida, his deeply personal reflection on the purpose and meaning of photography). To really be a photographer, you may also need to put down your camera, as painter Danielle Joy McKinney discovered.

McKinney studied photography formally, first at Atlanta College of Art, and later at Parsons School of Design, New York. What drew her to photography was its social impulse and its sense of urgency as a response to what is happening in a world that hurtles by at breakneck speed. “I was capturing the outside, the other, and observing public and private space, and how we can be guarded in those spaces”, she says. “It’s hard sometimes to enter that space of another person. Photography allowed me that lens of looking at another person and documenting it, and I enjoyed that.”

A momentary encounter on the train changed McKinney’s practice as an artist forever. While taking photographs, she saw someone crying, “but I wasn’t able to touch them”. The reminder of that distance created by the camera between herself and the things she observed and captured suddenly gaped in front of her. Her empathy wasn’t enough anymore. “I became very fatigued with watching and looking at the world around me, and making a statement about it,” she says.

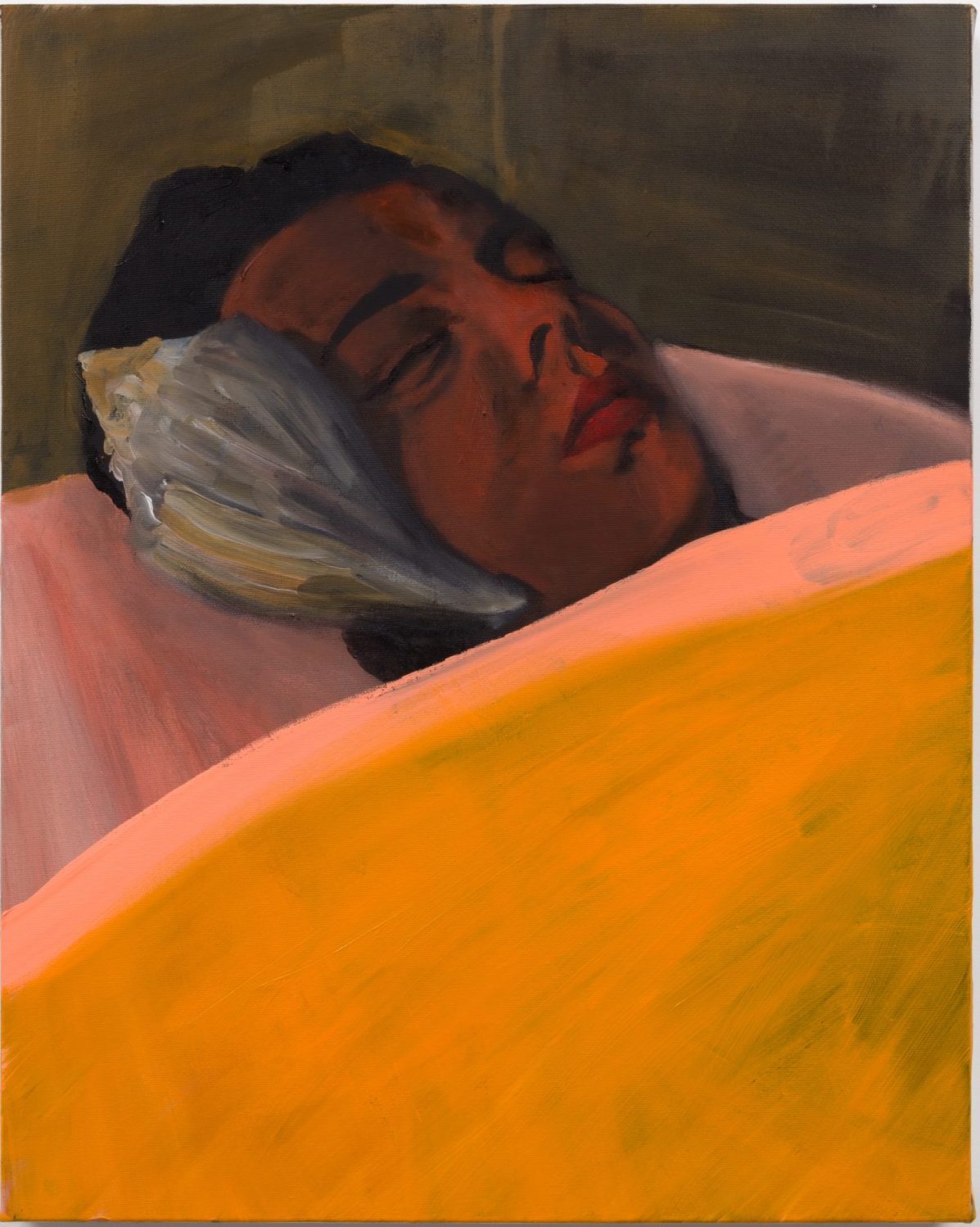

McKinney abandoned photography, but she hasn’t shaken its influence on her way of composing her images, and they are images that leave an imprint strong enough to appear even when your eyes are closed. While photography had challenged McKinney’s relationship with the world, painting was an inward exercise. “It was an emotional release: if I was feeling something in a relationship or personally, I would pick up a paintbrush”, she explains. “It became an obsession and I didn’t want to go back to photography and that reflective way of looking at the other.”

“I became very fatigued with watching and looking at the world around me, and making a statement about it”

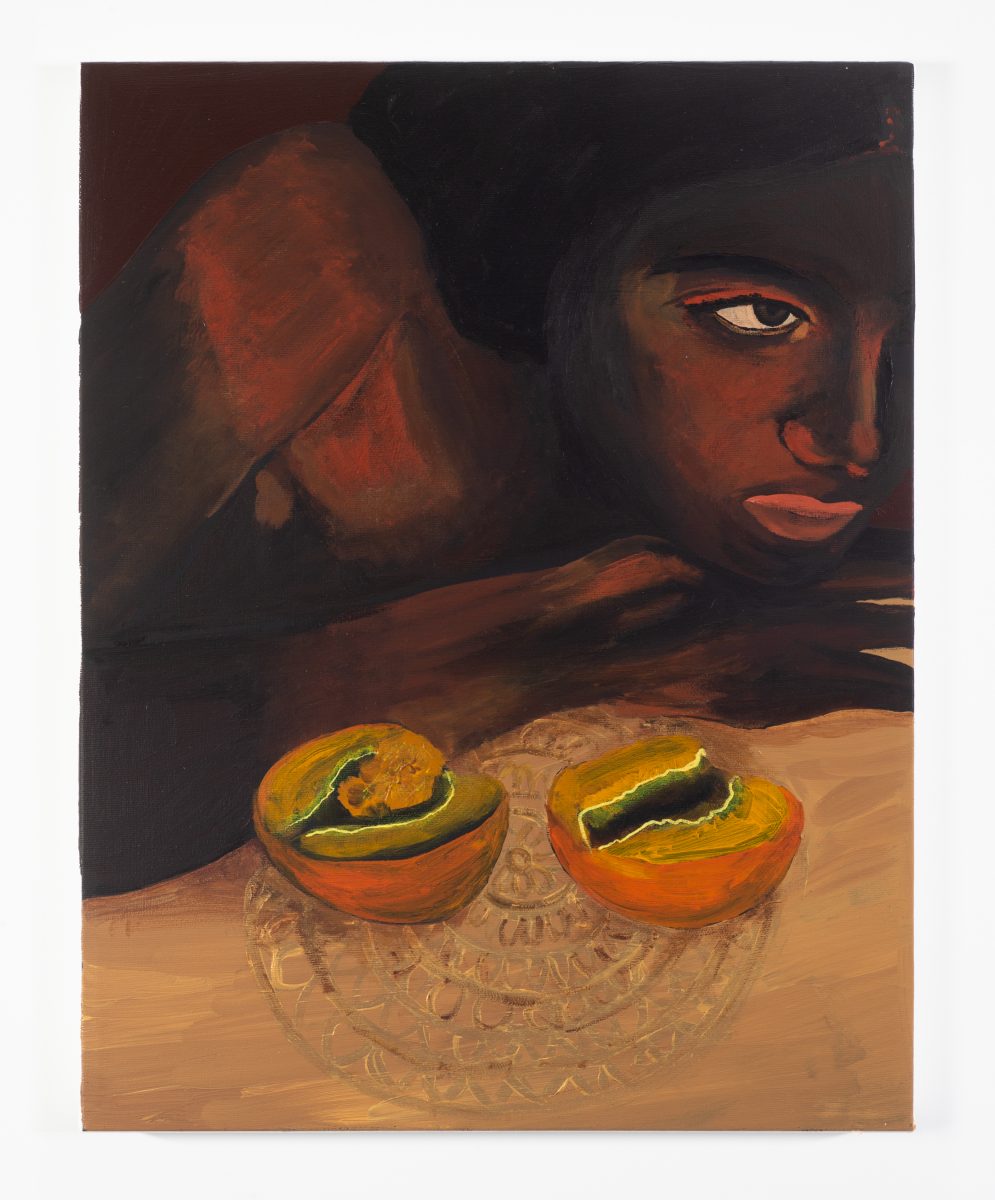

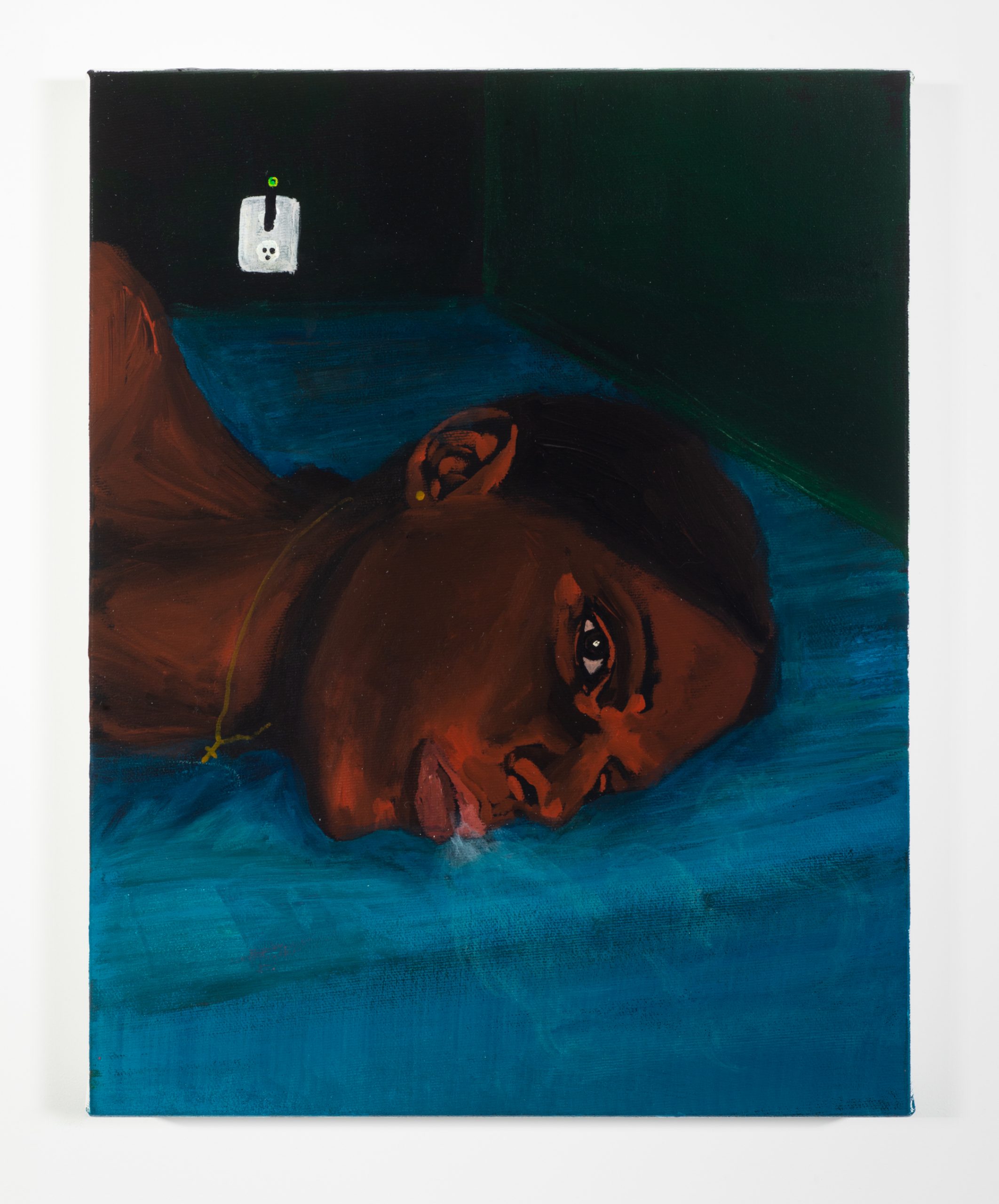

When we spoke, McKinney was about to open her first solo exhibition Saw My Shadow at Fortnight Institute, New York. It contained a series of paintings of languid figures, alone, ruminative, meditative, and contemplative. Their profound and prolonged gazes seem to echo the way McKinney used to look out at the world, searching for meaning by looking for the things, good or bad, that make us feel real and alive.

Her process as a painter still relies on photography for references, employing interiors often inspired by posts on Architectural Digest and Dwell’s Instagram accounts, pictures her husband sends her, and others images cut from magazines. “I travel through photographs,” she explains. “I used to cut out people and interior spaces from magazines for hours as a child, so I think subconsciously I go back to that.” Those references are then suffused with whatever emotion and feeling that she wants “to project into that moment”. Her paintings, unlike the photographs, aren’t indebted to anyone, and they don’t owe the viewer any explanation. They can exist autonomously, because their subjects don’t exist in reality. “The medium challenges the notion of what it represents. The paintings tell a completely different story”.

“A lot of my questions about spirituality and religion are projected into the paintings”

The strong storytelling aspect of McKinney’s paintings is one of its triumphs and most distinctive qualities. Her solitary, all female figures blur boundaries between the self and other, between McKinney and the world, neither straight self-portraits nor direct portraits. It’s also difficult to situate them in time or place. “I start out with the figure and then I’ll put her in an interior environment,” she says. “I don’t want the clothing to be too referential, but I’ll think about where the figure is, and I think about the texture and the colour. I want them to look classy. I don’t want them to be sexual.”

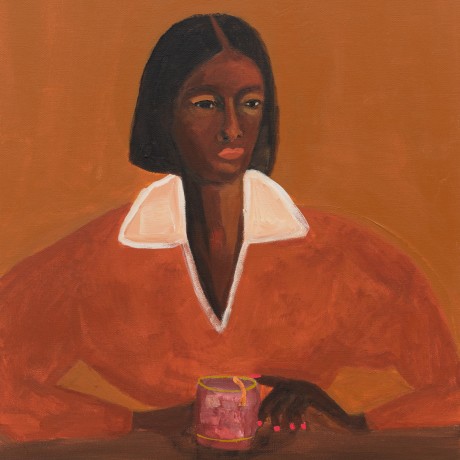

One of McKinney’s standout works is Negroni, an ambiently coloured, unforgettable painting, a simple image of a seated woman with a drink, and a wistful, even slightly woozy gaze. Although it’s based on a 1930s photograph, McKinney once again painted her own experiences into it: she had just found out she was pregnant (she is expecting her first child) and could no longer partake of her favourite drink. “Every night before I would paint I’d have two or three negronis,” she explains. “The drink represented so many things to me… but I couldn’t go there anymore. So I said I want to paint it, I want to paint where it takes me, and the absent-mindedness, how I feel when I’m at a bar when I order it and people say, ‘Oh, that’s so classy!’ The place it takes me when I get a bit tipsy.”

McKinney’s second exhibition Smoke and Mirrors at Night Gallery in Los Angeles is running now. When we talked over the phone, Negroni had already left her studio in order to be exhibited there. “I was so attached to her,” she admits. “When Night Gallery came to pick her up I cried. The figures are like my children in a way.”

Another regular motif in McKinney’s painting (alongside stylish interiors and great fashion) is cigarettes. “I’m going to be honest,” she says, “I smoked since I was 16, I’m almost 40 now. I liked the gesture of smoking. If I’m in a deep thought, it intensifies the moment somehow. It creates this atmosphere, almost a facade, but it also speaks to my addictive behaviour. It’s my comfort and my rebellious nature.”

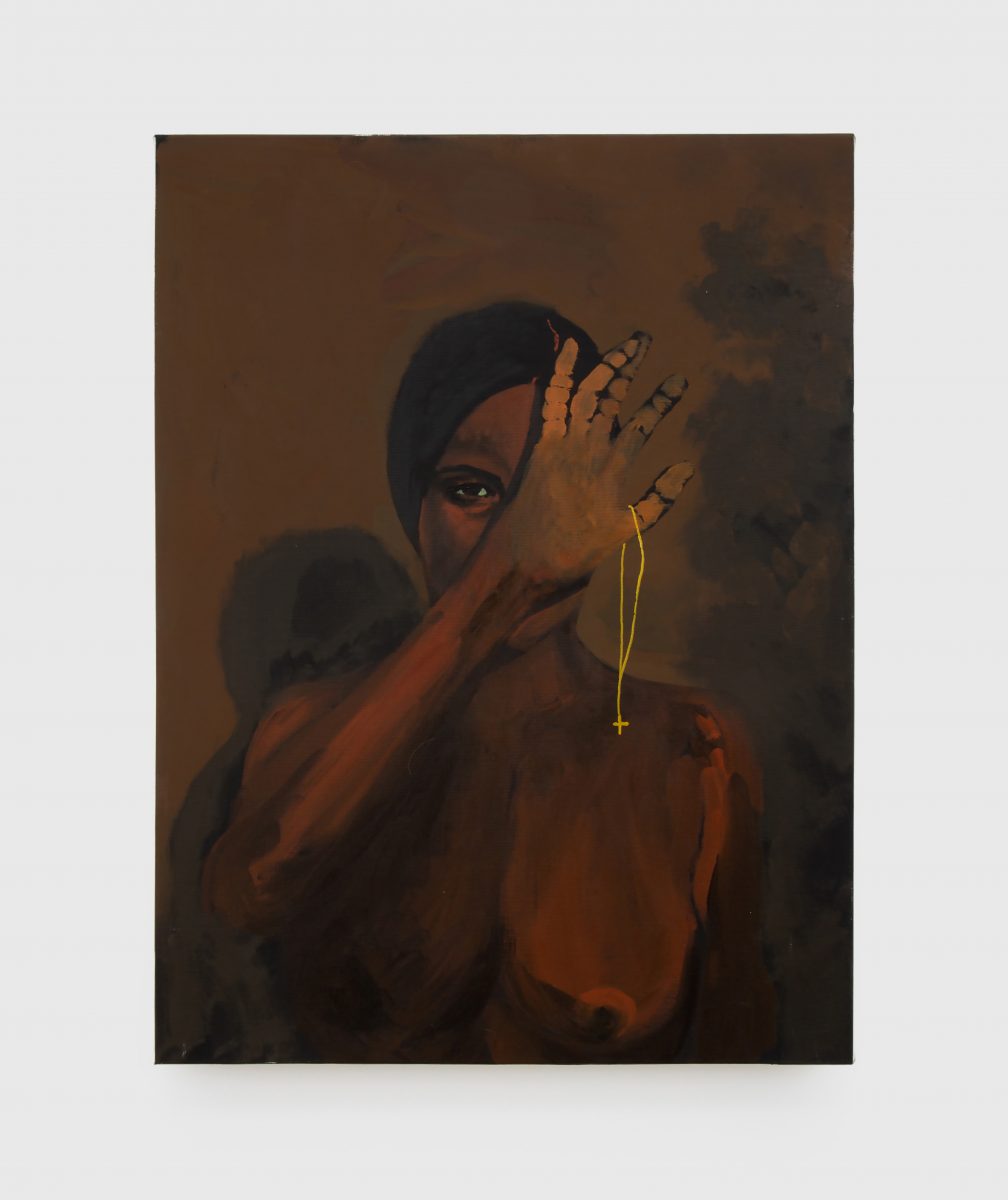

McKinney’s figures are quiet rebels, deep and introspective, but also concerned with the way they look. Face Mask with Prayer shows a woman topless on her bed wearing a face mask and sweatpants, a painting of Christ hangs on the wall in the background. In one image, a figure holds mala beads, while in another, a woman experiences a prophetic moment in front of a mountain. At Night Gallery, the painting titled Sixth Sense shows a topless woman holding up a chain necklace with a cross.

“The medium challenges the notion of what it represents. The paintings tell a completely different story”

“I’m very spiritual,” says McKinney. “I don’t follow any doctrine, but it is a formal practice for me that I feel I can lean on.” She was raised in Alabama, as a Southern Baptist. “My grandfather grew me up in the church, and there were religious icons everywhere. I think it still comes up in my work as a safety spot. A lot of my questions about spirituality and religion are projected into the paintings.”

What is striking about McKinney’s subjects is they aren’t any one thing, and their contradictions play out plainly. They recall Anaïs Nin’s words: “I take pleasure in my transformations. I look quiet and consistent, but few people know how many women there are in me”. McKinney might have turned away from looking out, but she has found just as rich an imaginary world within, and perhaps made even more profound connections to the human soul and psyche.

All images courtesy the artist