As far back as Greco-Roman times, nature has been characterized as a woman. Mother Nature, also known as Mother Earth, embodies the idea of a woman’s purpose, to follow nature’s design as care-givers. Much later, in the Romantic period of art and literature, women’s bodies were often placed in natural settings to encourage notions of femaleness—the idea of women as life-giving, nurturing, passive, fruitful and fertile, changeable and attuned to the mysterious, sometimes frightening, indomitable powers of the earth.

The Romantic era feminists—and feminists ever since—thought differently. Mary Wollstonecraft contested what was considered the “natural” place of women in the world. Women’s bodies follow cycles, and are capable of producing life—but does that mean we have an affinity with nature? If we go against what has been established as “natural” law, does that mean, conversely, we sever our ties with the earth? And in this age of the Anthropocene and extinction, is women’s connection with nature something that we should deepen and celebrate?

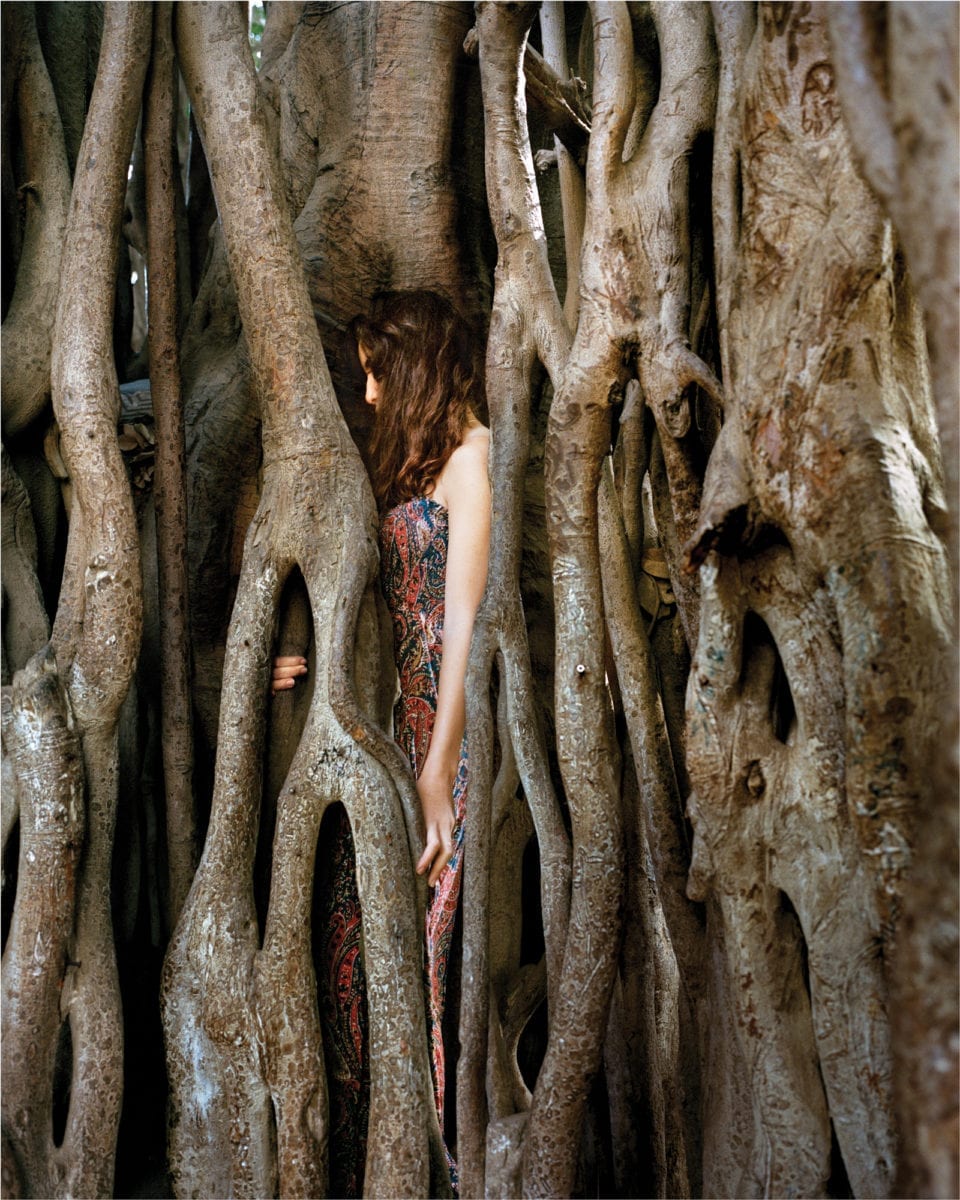

In unraveling this deep-rooted and complex question in the contemporary field, artists have returned to the direct relationship between women’s bodies and nature. Live Dangerously, a new exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, explores the ways twelve major contemporary artists have placed women’s bodies in pastoral settings in both disruptive and transformative ways.

Included in the exhibition are works by Ana Mendieta, an early pioneer of body art and land art, who forged new dialogues between her body and the environment, directly addressing the idea of the earth as the mother of humanity. Connecting her own body with the soil in literal ways was both spiritual and physical for Mendieta—merging with the earth was a ritualistic return. Mendieta embraced the feminine connotations of working with her body in the landscape—but not exclusively female in the binary sense. For Mendieta, being part of the earth is what connects all humans as a “throbbing whole.”

“Women’s bodies were often placed in natural settings to encourage notions of femaleness—the idea of women as life-giving, nurturing, passive, fruitful and fertile”

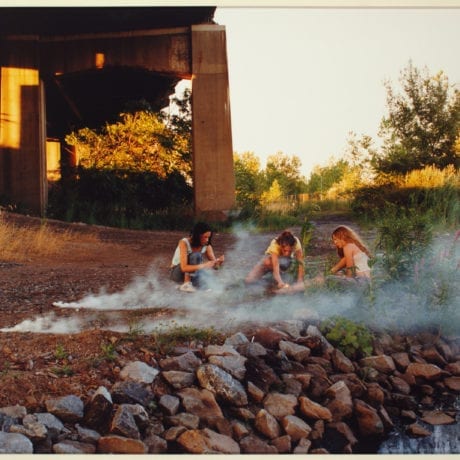

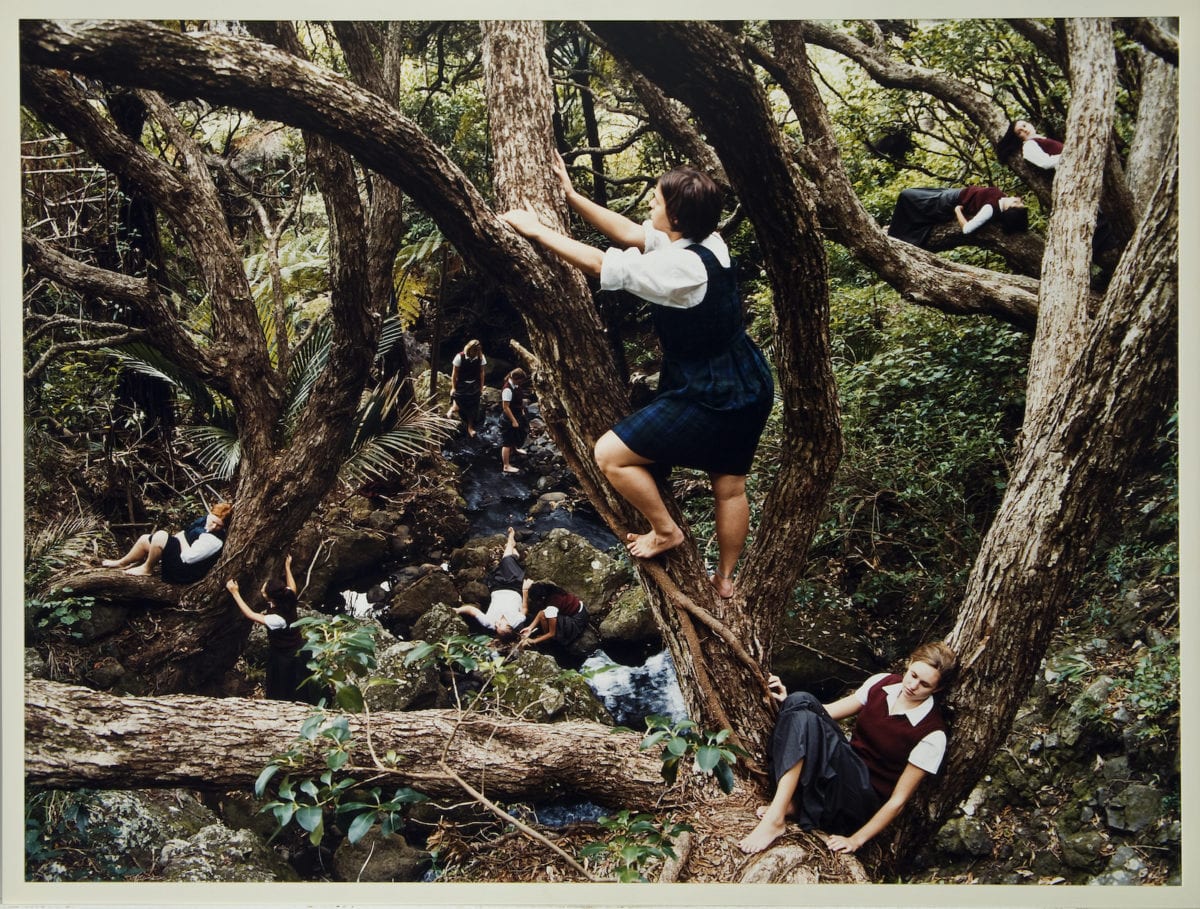

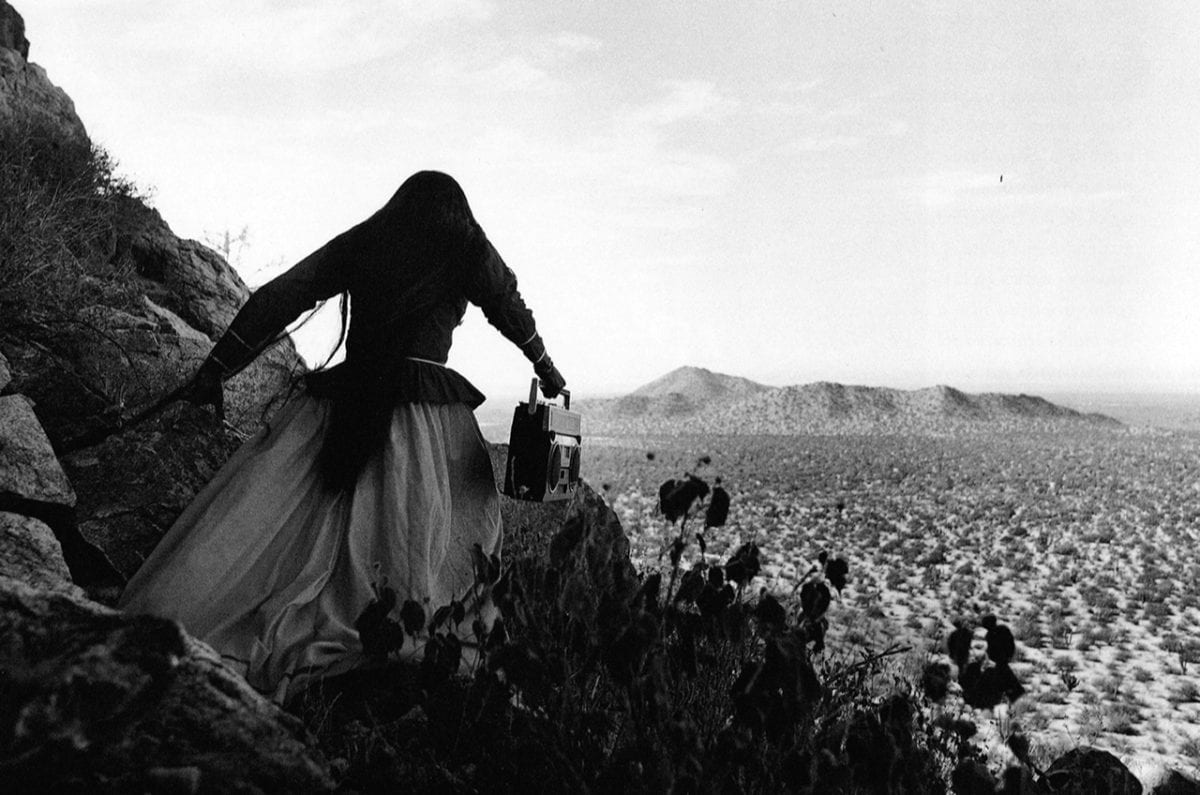

Working directly with the earth has been a powerful tool for artists who tackle gender and sexuality politics; contact with the earth serves a metaphor to subvert the idea of what is “natural”. Photographer Justine Kurland takes America’s rugged, rural and mythologised landscapes as locations for her Girl Pictures (1997-2002); her portraits present young women as empowered and dominating in the elements, constructing shelter, fires and fending for themselves.

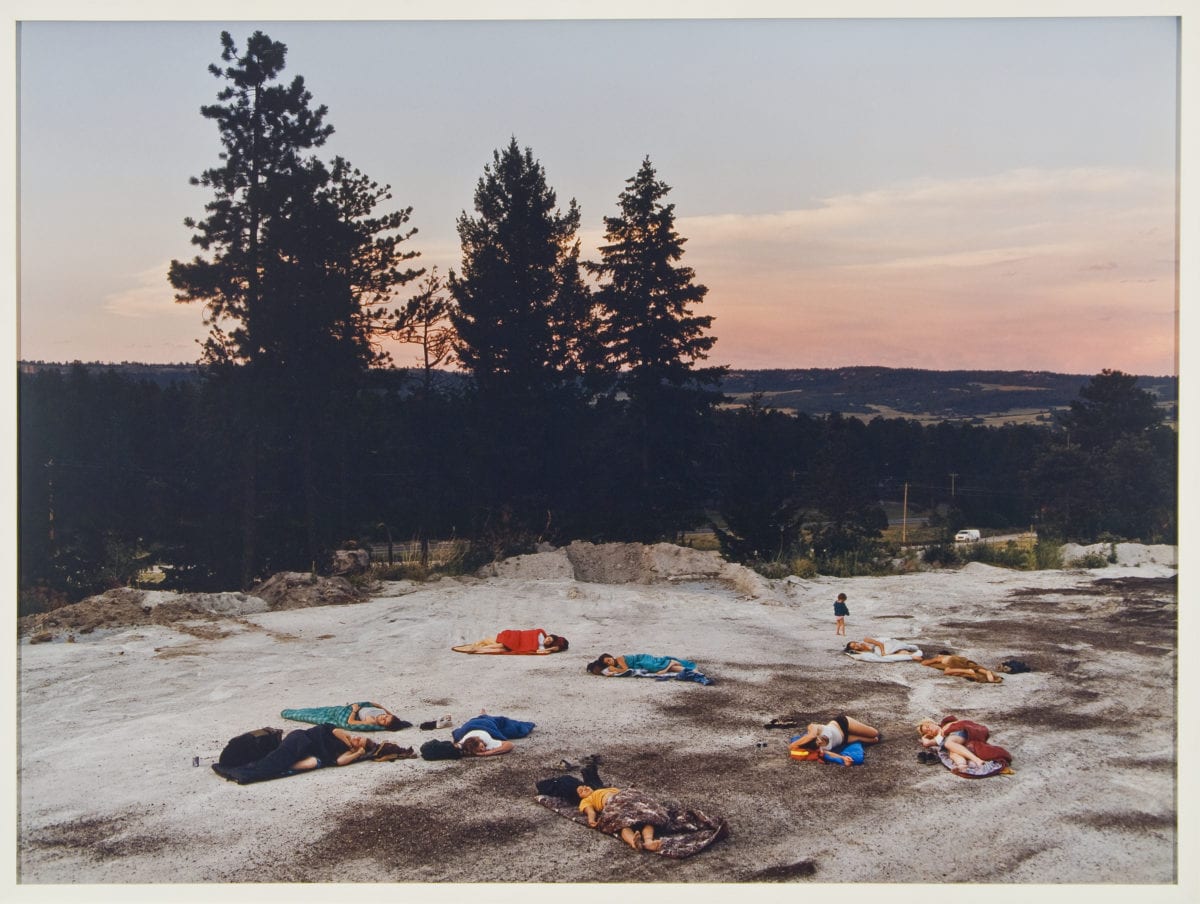

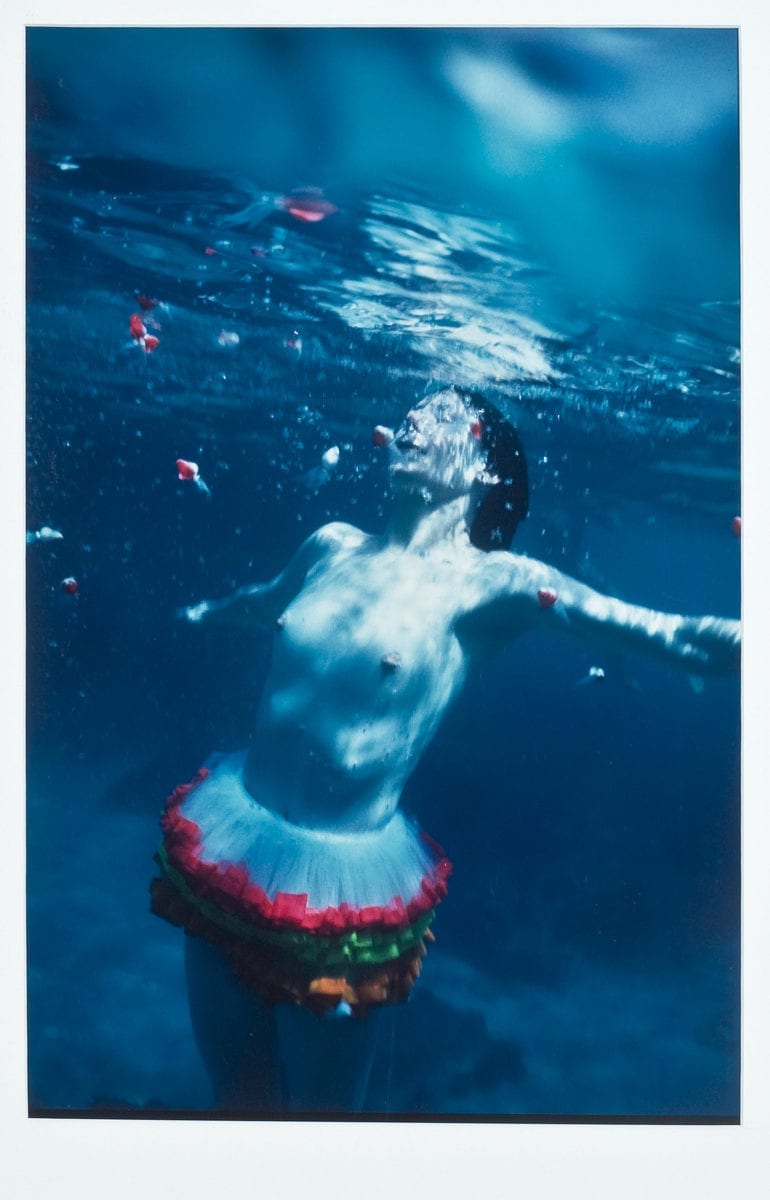

Also included in Live Dangerously are more than one-hundred works from Janaina Tschäpe’s 2002 series, 100 Little Deaths. Choosing sensuous topographical features usually near water, Tschäpe returns her body to nature as an organic form—linking her practice as an artist to the cycles ever-present in nature.

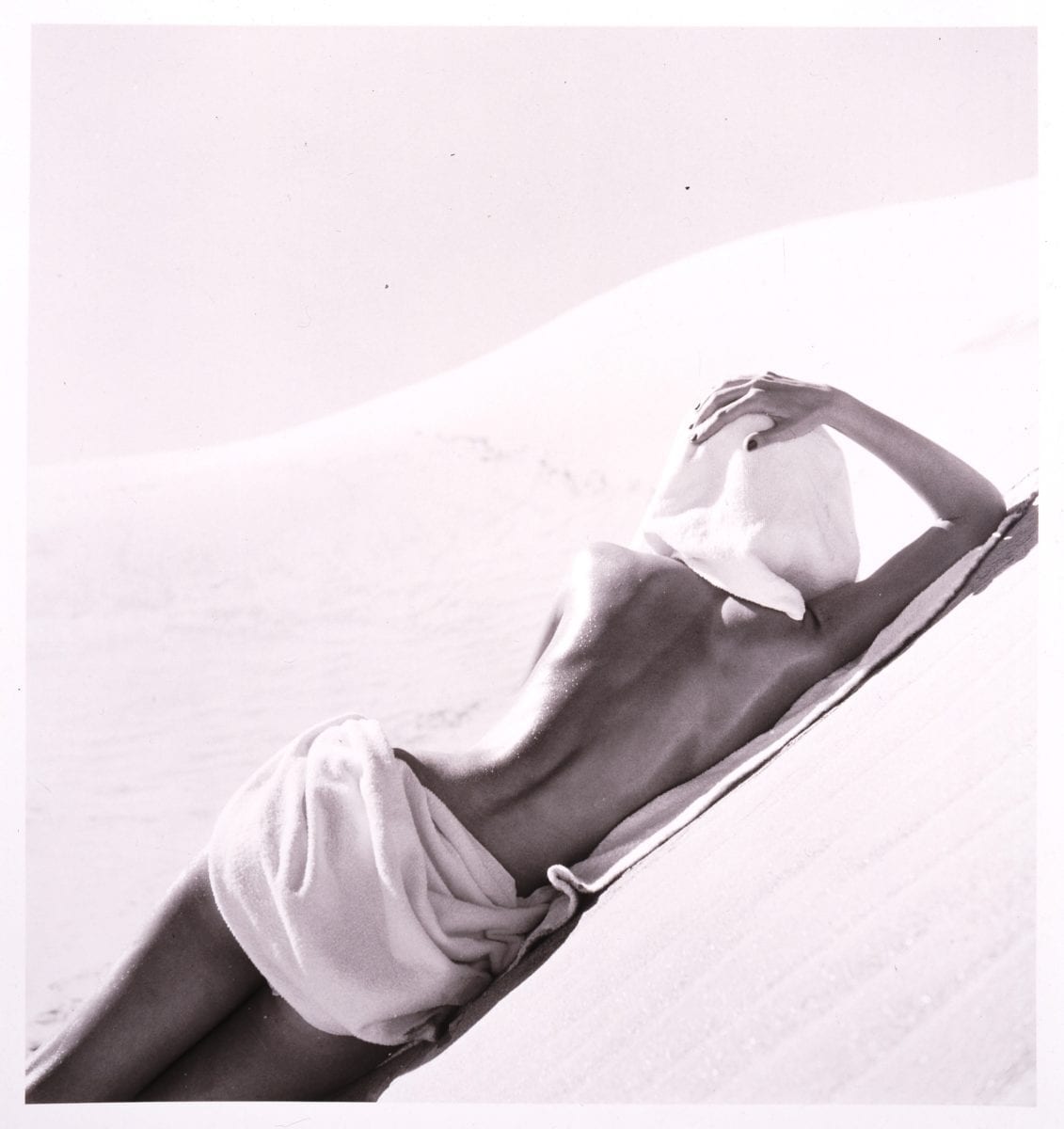

Sensuality becomes a statement for other artists in the exhibition—reclaiming the land as they reclaim their bodies. There is an undeniable eroticism in one picture shot in the Californian desert by the American photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe. A semi-naked model reclines on the sand, the curves of her body mimicked by the sand dunes. Looking at the picture now, more than seventy years after it was taken, it’s undeniable that there’s something transcendental shared between women and the natural world—and there are many more narratives to be told.