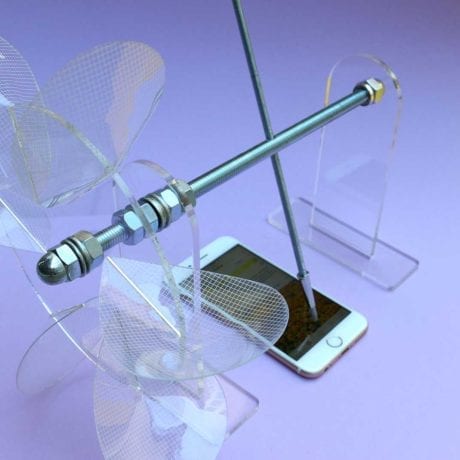

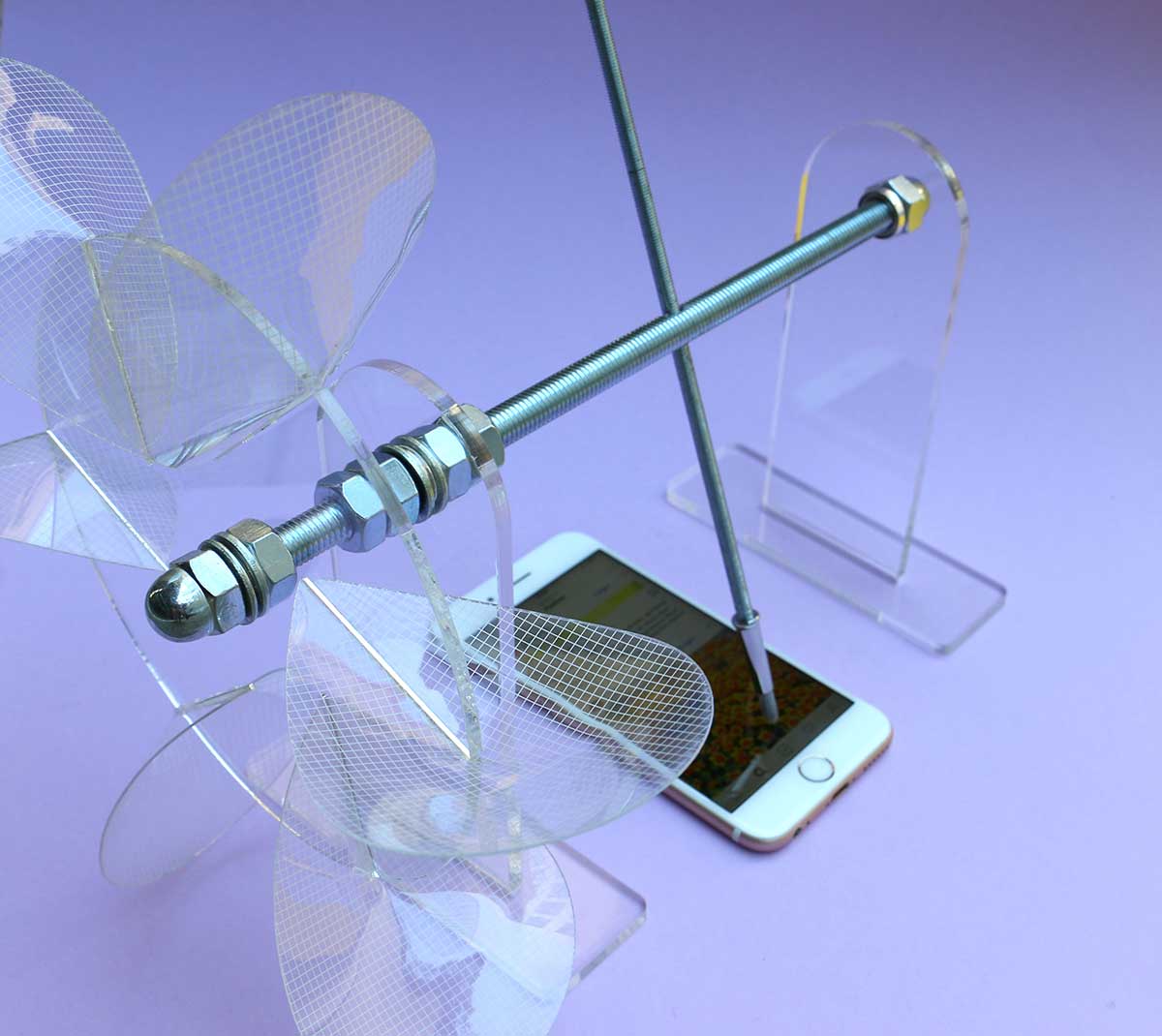

The gentle whir of a desk fan and the soft mew of a kitten provide the soundtrack to a triptych of robot fingers as they scroll, swipe and like into oblivion. Propped up by on-trend pastel plinths and shielded from inquisitive hands by acrylic containers, Stephanie Kneissl & Maximilian Lackner’s seductive project Stop the Algorithm (2017) conceals its rebellion against the social media gods it seems to serve.

By generating a random stream of activity on their smart devices, these machines intend to pop the filter bubbles generated by Facebook, Instagram and Twitter that keep users happy inside their isolated worldviews. Resisting one algorithmic system yet subservient to another, the schizophrenic trio perfectly embodies our fraught relationship with social media today, as a stimulant of depression and desire, FOMO culture and fabricated alter-realities. It is no coincidence that Kneissl & Lackner are the youngest artists to be included in All I Know Is What’s on the Internet at The Photographers’ Gallery in London; ultimately, their work helps rescue the exhibition from a conversation that at times feels several years too late.

“Resisting one algorithmic system yet subservient to another, the schizophrenic trio perfectly embodies our fraught relationship with social media today”

In the exhibition’s opening statement, curator Katrina Sluis outlines the lay of the land in the digital image economy: governed by mass quantity and expressed opinions (whether they belong to a human or algorithm is decidedly less important), it poses a direct threat to photography’s valorization of the individual image. Instead, Sluis maintains, the power rests in the hands of those who can make meaning out of this glut of imagery dominating the digital age. Tech giants like Google, Facebook and Apple have become deities by vending our data and making its continuous propagation compulsory.

Attempting to map the fluctuating role of photography onto this discussion, All I Know Is What’s on the Internet includes work that illustrates the colossal infrastructure of data centres and the many millions of human beings whose labour props up this digital ecosystem. Degoutin & Wagon’s sprawling World Brain (2015)—a two-part film with a run time of over an hour—dazzles with its architectural imaginary, bringing to a surreal visual light the unending fields of underwater data farms and high-frequency trading headquarters that comprise the physical infrastructure of the digital age.

“It’s no secret: the art world, being the art world, has unabashedly fetishized these gargantuan homages to a new digital order”

Once your dizziness subsides, the the film’s eye-popping pictures may start to look familiar; the duo have utilized much of the same imagery appearing within Metahaven’s 2010 publication, Uncorporate Identity, or the Big Brother-esque data farm installations by Simon Denny that have been knocking about art fairs and biennales since 2013.

It’s no secret: the art world, being the art world, has unabashedly fetishized these gargantuan homages to a new digital order. This idea is reinforced by Dutch artist Constant Dullaart’s #Brigading_Conceit (2018) nearby: a pair of silvery wings adorned with hundreds of SIM cards, neatly arranged and satisfying in their mindless repetitive order. These SIMs are a small portion of the many thousands Dullaart has used to construct his army of fake fan accounts—made all the more valuable through the phone verification process—on Facebook and Instagram. Once the fake account has been set up, the SIMs are often sold in bulk for the scrap value of the gold in the chip, generating a full cycle of industrialized output.

Dullaart’s reverence of the physical sprawl of the “like” economy is evident in this work, which the artist refers to as a series of “standing armies” that can be used against the validation systems of social media. But the “war” here seems to be less of a fight to disrupt the system than a sly acquiescence to its governing orders.

Five Years of Captured Captchas (2017) by Silvio Lorusso and Sebastien Schmieg is as close as you can get to an Origin of Species for the Internet age. The digital Darwinians captured every captcha they solved over the course of five years, transforming the lot into a five-book series that can be unfurled to a total length of 90km. Observing the visual evolution of captchas is fascinating, but tells us little of the technology’s changing function, or its murky present reputation (a US class action lawsuit was filed against Google in 2016 for exploiting the “free labour” of its users, whose captchas are used to train AI).

“Ultimately, the exhibition’s human interest remains limited to the role of the individual labourer within, and their manipulation by the multi-headed hydra of the digital image economy”

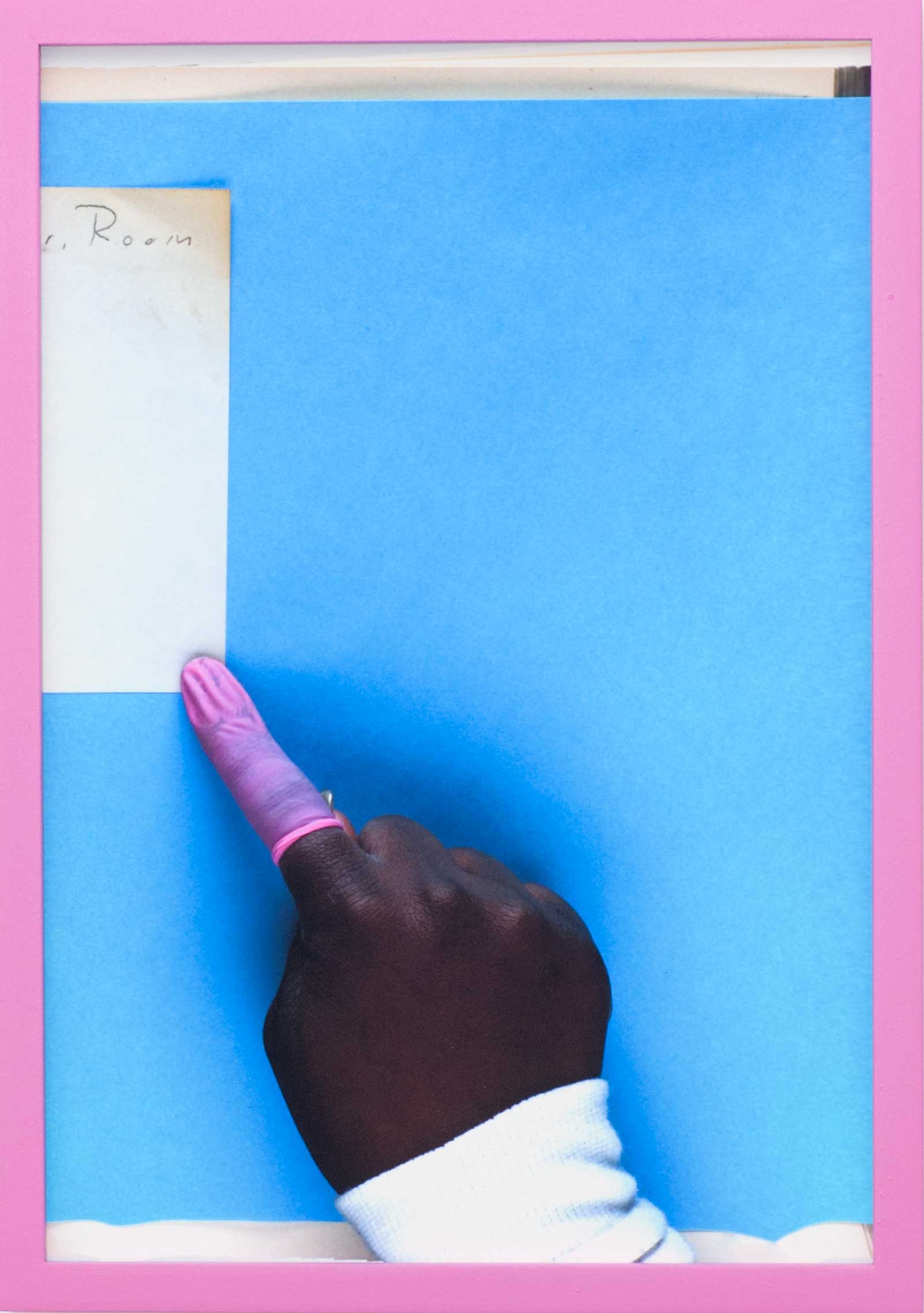

Despite these aesthetic accolades of digital image production, a keen interest in its human agents runs throughout the exhibition. Across from the captcha scrapbook is Andrew Wilson’s ongoing series ScanOps, in which the artist documents the human workforce behind Google’s literary digitization initiative. Carefully thumbing through pages of Google Books, Wilsen isolates the human errors that miraculously make it through the system: wayward thumbs cloaked in bubblegum pink latex gloves, or a hand caressing an ancient map.

Ten orbs of men scowling in various locations by Emilio Vavarella take a similar stance. The Google Trilogy 3: The Driver and the Cameras (2012) documents the accidental cameo appearances of Google Street View employees as they lean in to adjust the camera. With splodges of their faces blurred by the same algorithm that anonymizes accidental bystanders in Street View, there is a humorous and vaguely triumphant undertone to the work—as if suggesting a limit to the ability of technology to censor reality.

Eva and Franco Mattes, Dark Content, 2016

Eva and Franco Mattes of course make an appearance—you can’t even whisper the word “Internet” in a white cube space without them. The duo’s controversial project Dark Content (2016)—in which human moderators speak out on the everyday trauma of their jobs as “human algorithms” hired by anonymous companies to filter explicit imagery including suicide and homicide videos uploaded to social media—makes an appearance, as does the very meta Abuse Standards Violations (2016), whose self-censoring imagery practically guarantees its removal if photographed and shared online.

Ultimately, the exhibition’s human interest remains limited to the role of the individual labourer within, and their manipulation by the multi-headed hydra of the digital image economy. For all its focus on social media, there is little attention given to the social life of the internet—or the power in the popular. For all the destructive and malignant sides of digital culture, it has the rare capacity to bring people together in conscious acts of resistance—or creation.

As the state of global politics becomes increasingly dire, the realms of fact and fiction converge, and presidents troll Twitter like it’s some bad Reddit thread, addressing the role of digital culture from a contemporary perspective is more urgent than ever. Yielding to anachronistic, increasingly irrelevant distinctions between man and machine and fawning over big data architecture or the mechanics of Google Street View ends up missing the point entirely.

Only one of the eleven individual artists and groups featured in All I Know Is What’s on the Internet was actually born into a world already inhabited by the internet (1991 onwards). Kneissl & Lackner’s work is a call to disrupt the operating logic of social media; as a missive nestled inside a title that doubles as a hashtag, it is miles away from the largely backward gaze of the exhibition, whose recycled understanding of digital image culture forms a stale feedback loop—in other words, the very “filter bubble” that Kneissl & Lackner are so against.