Creativity is in Maren Hassinger’s genes. The artist has long believed that the genes we inherit from our parents guide us instinctively to the careers that we choose to pursue. In Hassinger’s case, her father, Carey Kenneth Jenkins, the first Black architectural professional to graduate from the USC School of Architecture, introduced her to creativity and sparked her imagination.

Hassinger began dancing when she was just a child. She then attended Bennington College (paid for out of pocket by her father) as a dance major and recalls stepping into her first class and feeling that the other students were questioning why she was there. Hassinger realised that she wasn’t born with the body that is typically associated with dance, nor did she have the same private class training as the others. She refers to it as a reckoning, saying, “I feel like it’s the tragedy of my life that I was never able to be a dancer in a professional capacity.”

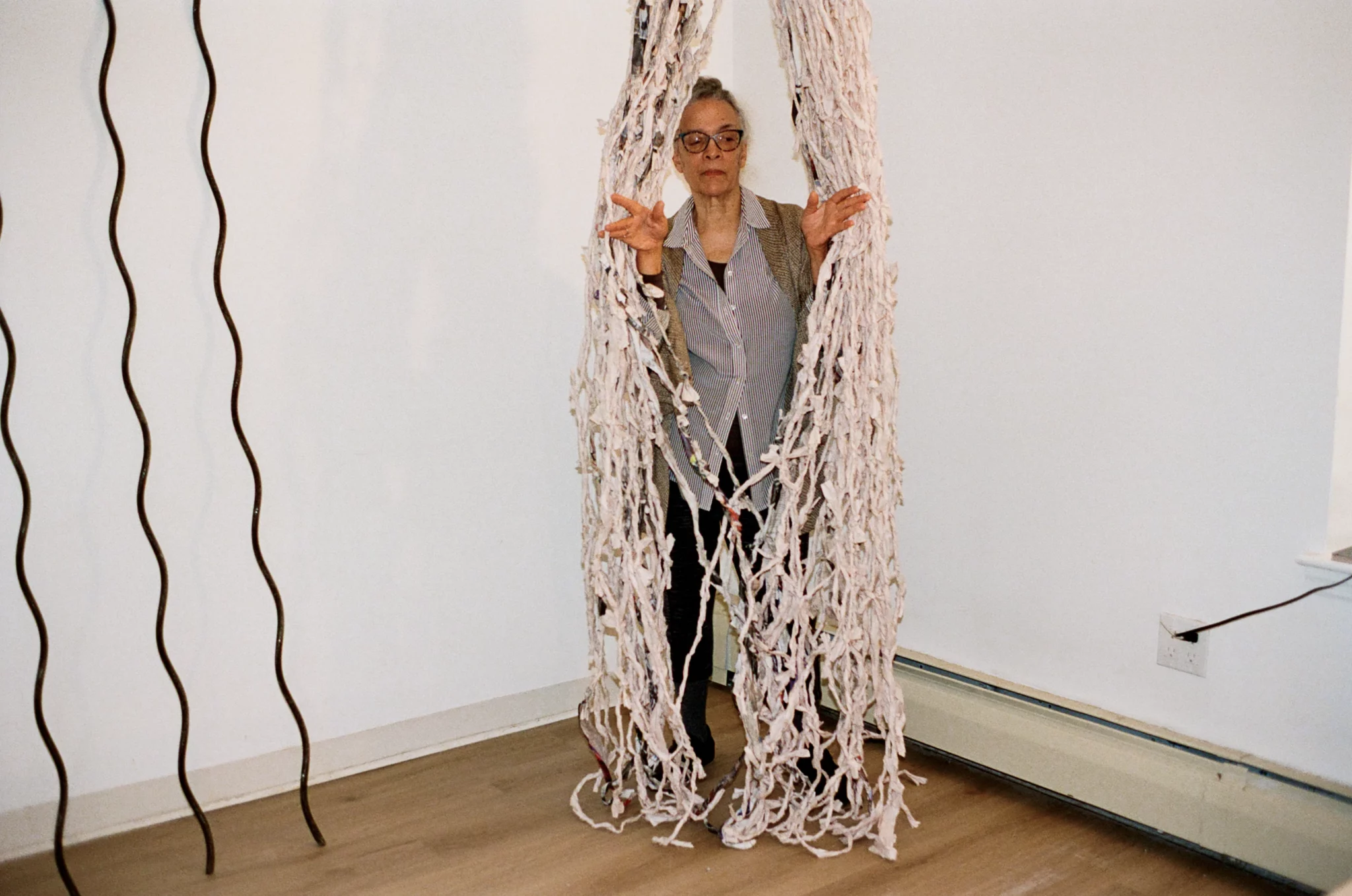

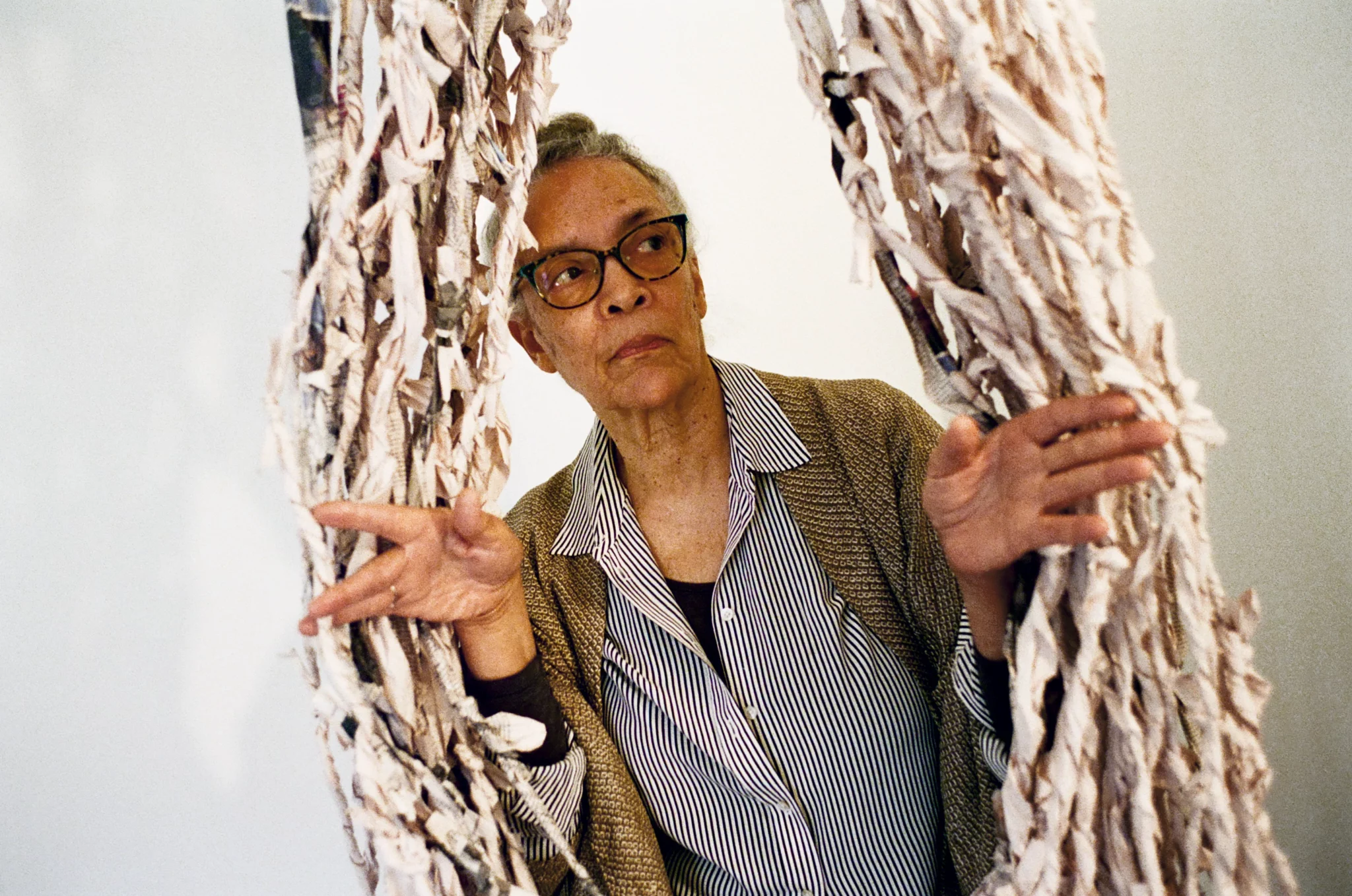

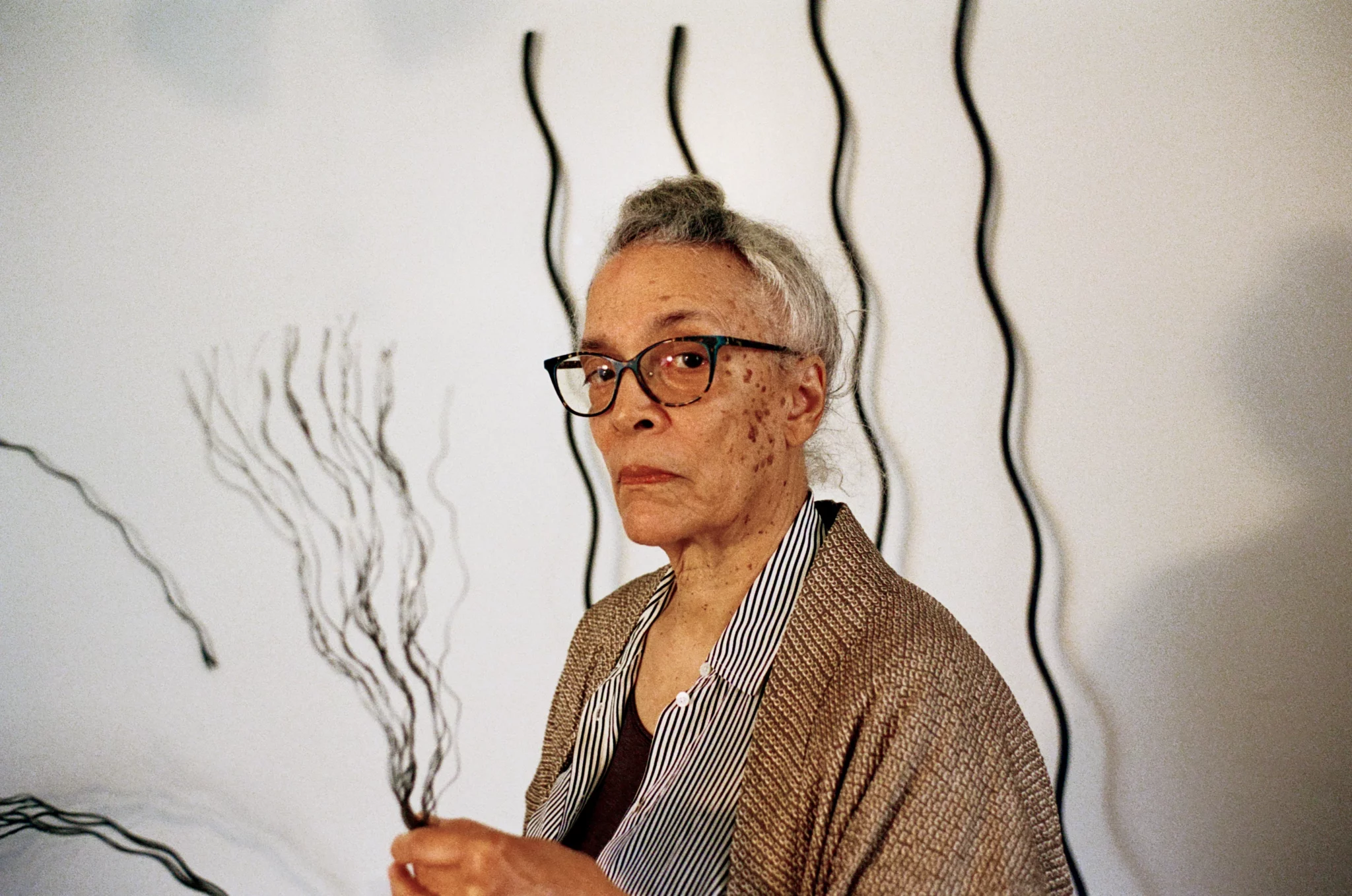

While she notes that she was initially depressed about giving up that dream, looking back, she is thankful that her art career has brought everything to her. As she says, “It gave me my life.” Hassinger soon found a new method through which she could continue to express herself creatively. She began to work in sculpture during her undergraduate years, graduating with a bachelor’s in the medium in 1969. Afterwards, she enrolled as an MFA student at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, graduating in 1973 with a graduate degree in fibre. At a junkyard, she made a fortuitous discovery of wire rope, a material that has become a hallmark of her practice and which she still utilises today.

Though her dream to be a dancer did not pan out, her training, specifically qualities of movement, found its way into her sculptural work. Hassinger’s installation, On Dangerous Ground (1981), which is composed entirely of wire rope, a material that is generally difficult to manipulate and shape, is an example of the artist’s ability to integrate her dance background into her art. It foregrounds her capacity to produce work that exists between motion and static. Engaging with Hassinger’s work, whether in person or in images, there’s a notion that they are dancing in the space. Hassinger has always been interested in movement. This dedication to movement can be seen in pieces produced early in her career, like Whirling (1978) and Leaning (1980). Both feature bundles of wire rope shaped by Hassinger, giving the impression of moving across the floor.

Observing Hassinger’s work and its source material, it might be easy to forget that the artist has long stated the imbalance between humans and nature. In a 2018 interview with Lowery Stokes Sims for Bomb Magazine, the artist stated that our relationship with nature will be different than that of previous generations because of the harm we continue to perpetrate. Elaborating on this during our conversation, Hassinger says that she hopes the inventiveness of people like scientists and farmers will be able to meet the pressures of the changes of the earth that continue to occur by finding things to eat and shelters that can accommodate the new ecology. “Things don’t have to get worse. We can evolve. We’ve evolved before. We have to change,” she says.

In her late 70s and having endured an art world that wasn’t always welcoming to Black women, Hassinger radiates an infectious positivity. Though she has been producing and exhibiting for decades, it has only been recently that the artist has begun to receive institutional recognition, from having her archive acquired by the Getty Research Institute to upcoming exhibitions being lined up years in advance. When asked how it feels to finally have her work and contributions to art acknowledged, Hassinger answers that though she is gratified and happy, she didn’t realise it would take this long. She shares that she assumed she’d graduate from college and instantly find success. Her experience in the art world has included both encouragement and discouragement, but “I never thought too much about the discouragement.”

It’s this calm and self-assured attitude that has aided Hassinger in her career, as she shares she doesn’t have an ego about her work or the installation process. That’s not to say she doesn’t have ideas or opinions about how she’d like her work to be presented. She says that she largely has the freedom to install work how and where she envisions unless it must be changed for logistical reasons, such as being unable to be hung from the ceiling because of its weight. Elaborating on how her relationship with galleries and museums has changed throughout the years, Hassinger notes that in the early years of her career, there were moments she felt critiqued and uncomfortable because curators were attempting to control how the work would be presented. As time has passed, though, she has come to understand that while they could and do make changes, they’re not controlling her ideas. Her work is still a manifestation of herself.

When asked if she considers her work to be radical, Hassinger answers no. Hassinger says she thinks about human relationships a lot when creating and questions why people can’t get along better. She argues that she believes it has to do with competing against one another and the need to win. The artist’s assertion that her work is not radical can be read as a refusal to acknowledge human decency as “radical.” Hassinger relates this inability to get along to what she sees as a refusal to accept that we are all related. She says, “To keep fostering that idea is hateful. What is the point of that?”

It’s difficult to argue against Hassinger’s claim that genetics have played a significant role in her career as an artist. But it can’t be overstated that she has also cultivated and constructed her own life. A life in which she can create. When asked what the most pivotal moment of her career has been, she answers that it was when she decided to commit to art. Discussing the possibility of failure at the beginning of her career, the artist says that she was aware she could fail miserably and starve to death, but due to her ambition and her belief in what she had to say with her work, she didn’t think that would happen. The decision to become an artist, while it may have been risky, wasn’t a bad one. Hassinger proclaims that you only have one life, and if you want to do something, you should do it:

“It’s your life. Not their life. Give it a chance. Give it a go. If it doesn’t work, you can always change. You can have many jobs, many professions,” she says.

Written by Karla Mendez