This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

I prefer to encounter art alone. It’s perhaps a puritanical streak: I want my response to be completely unmediated. It’s also impatience: I like to move on quickly if I’m not drawn to linger. I don’t want to be held back by someone else’s pace. If I arrive at the end of an exhibition and have to wait, I find irritation biting at my body, my pleasure, as confusion and interest in the artwork leaks out of me.

In fact, it’s worse. I don’t enjoy the gallery environment at all unless I can view an exhibition alone, in my ideal situation. For this reason, I don’t go to galleries very often and my art experiences are mediated by other ways of seeing, through a screen, in a book, on a postcard.

In late winter 2020 I visited Los Angeles for the first time. I was overwhelmed by what it was possible to do in LA, by the cities within a city. With so much ground to cover, I felt the intimidation of choice, of FOMO, of making the wrong decision. Everyone recommended the big galleries (The Getty, Los Angeles County Museum of Art), their cities within a city of exhibits. But I was craving an intimate experience that might ground me for a short while in the cacophonous possibility of LA.

Looking through what shows were open I felt immediately drawn to a newly opened exhibition of the late American artist Ree Morton, whose work The Plant That Heals May Also Poison was listed on the website of the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles. Boldly colourful, physical, playful, erotic, beautiful, her work brought to mind that of Anthea Hamilton, in particular the last show of hers I saw—The Prude—with its giant quilted butterflies, alabaster knee-high boots and Battenburg-fur panelled walls.

I had the immediate impression that the work had the potential to deeply affect me both in my mind and in my body. I want an artwork to offer a feeling response, rather than a thinking one. I feel first, I think later. Perhaps that is why it’s easier for me to be alone when I encounter art, to have that space for the feeling to enter and experience in my body. I only want to think it out in conversation much later.

“I was far from home and was trying to isolate and then eradicate my feelings of loneliness. Morton’s work overpowered my will”

It was early morning, so I decided to head to the gallery after breakfast and see if I could enjoy being there alone just as it opened. Upon my arrival I discovered that the gallery was also a venue for voter registration. While this disrupted my desire to be alone in the space, I felt happy to see people trailing into the gallery and leaving with their ‘I’m Voting’ stickers. I was yearning for an intimacy that it can feel hard to access when travelling solo. As I looked at the people registering to vote I felt an intimacy of sorts – an assumed shared political intent – and was grateful to every stickered person I saw.

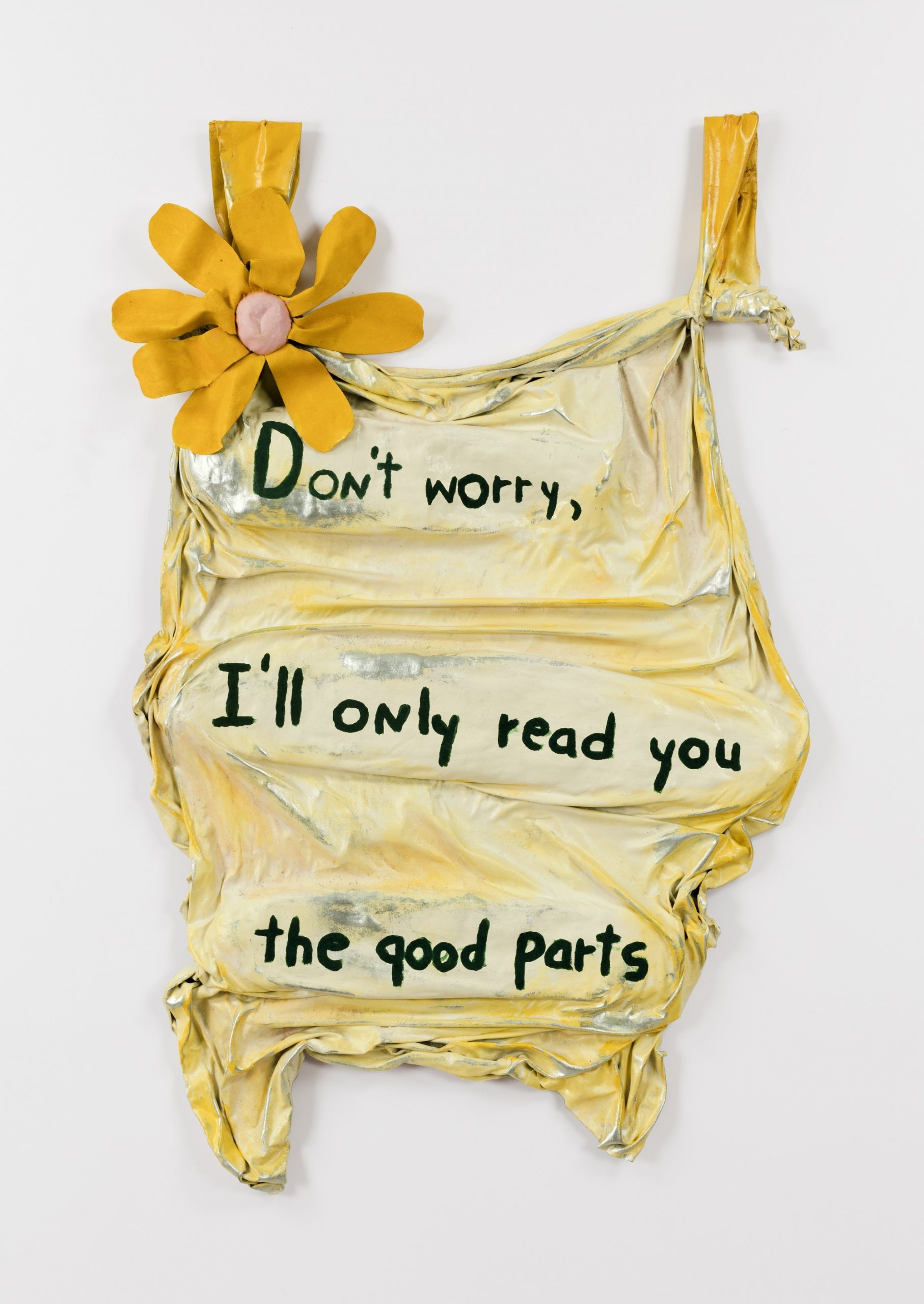

It was in this emotional state that I encountered Ree Morton’s work, my want-to-be-alone desire trembling against my need-for-connection desire. I loved everything I saw: her early, tentative drawings, embroidered flags, paintings, a sculpture of a see-saw. But the pieces that moved me the most were her bright wall-hung sculptures created using celastic, a fabric that you can mould and then set using a solvent. It has a strange look about it, almost like papier-mâché but both waxier and more plastic. It has a quality of warping, giving way and being caught between two forms.

Of these celastic pieces Don’t Worry, I’ll Only Read You the Good Parts

(1975) startled me because I began to cry in front of it. The words of the title are painted in black onto a pale butter-yellow panel. Slightly grubby, it drapes and swags at the edges like a magnificent Grecian robe, but also like dirty laundry dropped on the floor for someone else to pick up. It has a yellow flower pinned to the top left of the panel – the shape of a daisy a child might draw. It reminded me of a photo I took once near to my home, in Peckham Rye Park, South London, of a daisy picked to make a daisy chain necklace for my young niece, dropped into the lap of my yellow cotton skirt.

At the exhibition I learned that Morton was a mother of three and in 1977 she died in a car accident at only 40 years old. That likely contributed to the crying. Don’t Worry, I’ll Only Read You the Good Parts felt like a tribute to the service of others, a tender promise that the “you” addressed would be spared painful realities the speaker would bear the burden of themselves. It suggested to me an intimate knowledge of the person being addressed, that the speaker could easily separate the good from the bad bits of a story as the “you” might have experienced them. It was the promise of a mother or a friend.

“I cried because I heard the voice of this artwork as weary. It was a voice that denied itself so as to create comfort for others”

But the title of the work also made me wonder if it spoke to self-censorship, an abandonment of feelings you might want to share or ask others to pay attention to. The “you” the piece addressed, who was not trusted enough to give their full attention to the speaker. In looking at it, I felt the burden of women’s speech. If I speak, what should I say? Will my tone of voice, the words I use, entice or repulse? Will I be listened to or ignored? Will I be believed? What must I leave out to keep myself safe?

The suggestion of clothing and laundry in the unruly shape of the panel, the explicitly handmade quality to the artwork, made me think of women’s labour. The flags I’d seen in the exhibition, the pageantry of the ribbons and other adornments, reminded me of trade union banners. I began to reimagine Morton’s titular words, Don’t Worry, I’ll Only Read You the Good Parts, appliquéd alongside the flower as an emblem. I speculated on what heraldic motif would be best to add. I imagined taking up that banner and being its bearer.

I cried, I think, because the piece was so tender and spoke to me so intimately. I was far from home and was trying to isolate and then eradicate my feelings of loneliness. Seeing Morton’s work overpowered my will. I thought of all the times a friend would say to me, “Don’t worry Ames,” or send a text to me, “dw bb”, adding, “I love you.”

I cried because I heard the voice of this artwork as weary. It was a voice that denied itself so as to create comfort for others. I heard myself say, “Don’t worry, I’ll only read you the good parts.” I had caught myself in a lie.

Amy Key is a poet based in London. Her debut poetry collection, Luxe, was published by Salt in 2013. Her second collection, Isn’t Forever, was published by Bloodaxe in 2018. She is writing her first non-fiction book.