The visual art of video games surrounds us, in seemingly endless forms; it pervades our consciousness, more insidiously than any other kind of picture, sculpture or film. We glimpse pixelated sprites as street art mosaics; we lapse into dreams of tumbling Tetris bricks or Minecraft landscapes; we’re haunted by the CG demons that lurk in the labyrinthine realms of Bloodbourne or Doom. In recent years, video games have increasingly featured in museum collections, including MoMA, the Smithsonian Institution, London’s Barbican Centre (whose Game On exhibition

has toured international venues including Tokyo’s Miraikan), and the V&A London’s current acclaimed Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt, which transfers to its Dundee venue this April. At the same time, video games resemble curious interlopers in the contemporary art world; the loose-change arcades and home consoles that I grew up with would never have qualified as “high culture”.

“There’s this ongoing question of whether video games are ‘art’; certainly, a large element is design and process” says Kristian Volsing, co-curator of the V&A’s Videogames exhibition with Marie Foulston. Notably, the V&A’s show takes a contemporary perspective, rather than the “history of gaming” nostalgia of many other exhibition; it acknowledges that video games are a solid cultural currency, even as its tech and titles continue to shape-shift.

The V&A pinpoints a defining moment in the first decade of the twenty-first century, with a “democratization” of tools used to develop video games, and wider access to smartphones, broadband and social media, making video games and their art a mobile/mass experience. “There has been a real sea change in the way that people are seeing and responding to video games,” explains Volsing. “It reassesses what video games portray, who they’re for… you start to get a lot more personal stories coming through, including representations of race and LGBT communities. Different viewpoints and visual styles did exist in the past, but new platforms have opened up for these spaces, both online and offline. The titles we’ve chosen have made an impact that continues after their release.”

No Man’s Sky – TM/© 2016 Hello Games Ltd. Developed by Hello Games Ltd. All rights reserved

In Videogames, we experience a genuine sophistication of vision at play with direct emotional hooks. Its visual displays present a heady range of approaches – whether it’s a mesmerising big-screen projection of award-festooned “indie” magic realist adventure Journey (2012), or concept artist Hyong Taek Nam’s vivid character sketches for “AAA” (big-budget studio) smash hit The Last Of Us (2013). Its climactic gallery is a DIY arcade that feels like some cyberpunk domain; some of the simplest games in this subversive space (such as the fleeting, text-based Queers In Love At The End Of The World) are memorably moving.

“One of the most interesting things to happen in the last decade or so is the rise of “indie games,” says Ian Milton-Polley, translation expert and writer at Frognation: a game script and localisation company based in London and Tokyo. “Small independent teams of games developers obviously can’t compete with the 700-strong teams of AAA studios, so you get this wonderful blossoming of visual aesthetics. The visual art of Journey is really abstract – but painterly, rather than pixelated. It’s awe-inspiring how a game with such simple geometric shapes fills you with an emotional resonance at its conclusion. I found it really affecting as a mood piece.”

- Kentucky Route Zero. Courtesy of Cardboard Computer

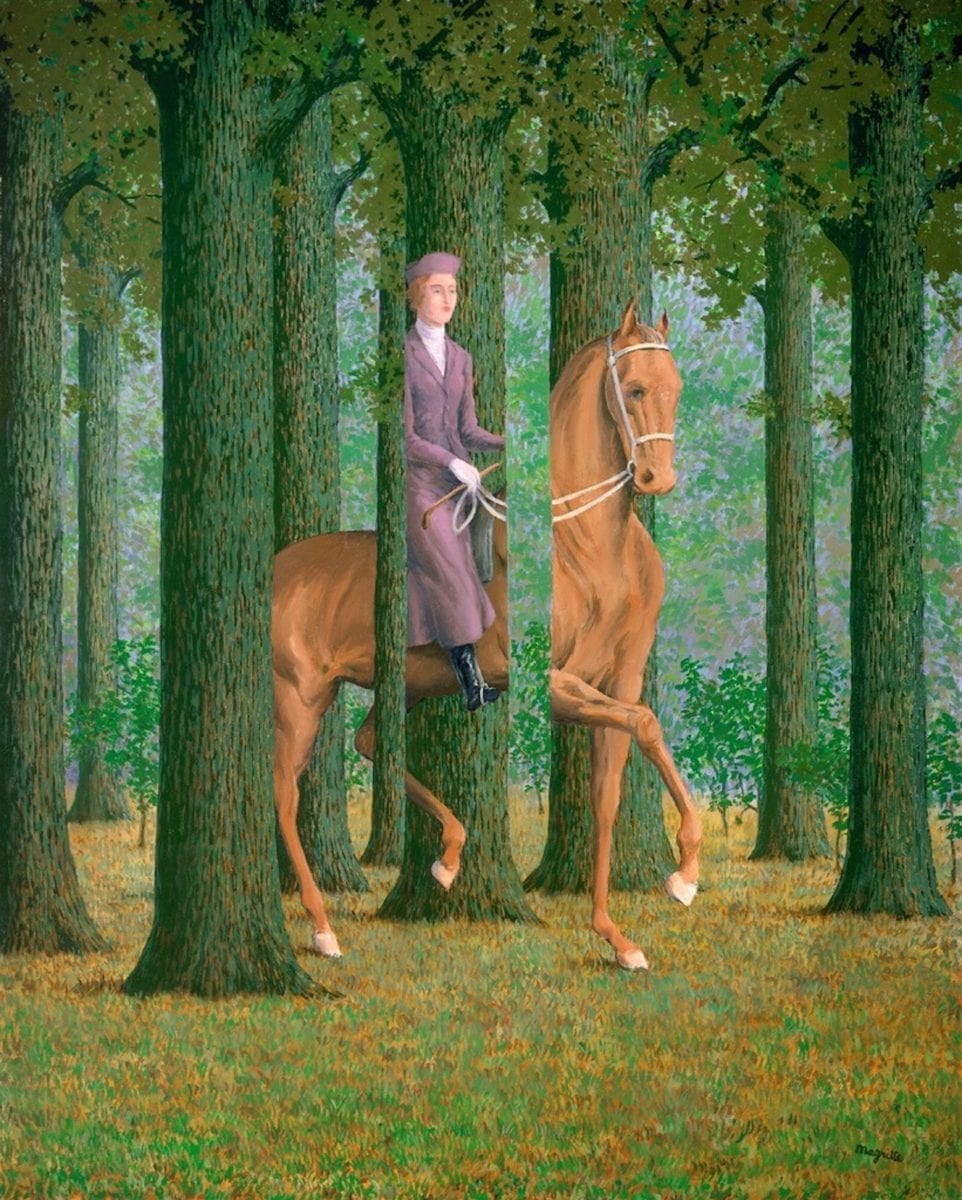

- Le Blanc Seing, 1965 by Rene Magritte. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington

“It’s awe-inspiring how a game with such simple geometric shapes fills you with an emotional resonance at its conclusion”

Milton-Polley also highlights the surreal odyssey Kentucky Route Zero (2013) as a pivotal ambassador of indie gaming innovation: “It’s really beautiful, clever, brilliantly written, and the visuals contribute to the Lynchian atmosphere.” At the V&A, a forest scene from Act II of Kentucky Route Zero is projected above the illusory art that inspires it: Magritte’s 1965 painting Le Blanc-Seing.

Another call for video games as creative tool comes in the form of the Realtime Art Manifesto (2006) created by artist duo Tale Of Tales, aka Auriea Harvey and Michael Samyn (who originally met “in cyberspace”, and are now based in Ghent irl). They argue that “Realtime 3D is the most remarkable new creative technology since oil on canvas”, and their manifesto is both urgent (“Do not fear beauty! Do not fear pleasure!”) and obstinate (“Don’t make modern art”). The pair have experienced the risk-averse nature of the AAA gaming industry (one of their ambitious projects, a reworking of Sleeping Beauty, remains unfunded so far), yet they’ve also realised some extraordinary “post-games”; at the V&A, you can play The Graveyard (2008)

, guiding its elderly female protagonist through its richly layered black-and-white cemetery setting: a reflection on mortality, and an antithesis to the frenetic speed usually associated with video games.

Blue Sky Concept, The Last of UsTM ©2013, 2014 Sony Interactive Entertainment LLC. The Last of Us is a trademark of Sony Interactive Entertainment LLC. Created and developed by Naughty Dog LLC

Contemporary artists continue to play with the immersive/emotive potential of video gaming. Killbox (2015) is an online game and interactive installation created by artist Joseph DeLappe and Scottish developers Biome Collective, which exposes the dehumanisation and atrocity of drone warfare. Elsewhere, VR is used to powerful/nightmarish effect in Jordan Wolfson’s gory beat’em-up simulation Real Violence (2017), and in Rachel McLean’s distinctly trippy I’m Terribly Sorry (2018). In an interview with The Evening Standard, Maclean explained: “[With film] you can’t just throw somebody into an experience and expect them to be scared or sad. But there’s something so immediate about VR. And the times that I’ve tried it, you can very readily feel scared or disorientated.” In I’m Terribly Sorry, Maclean aims for a “zombie first-person shooter feeling… except that instead of a gun, you have a mobile phone – the only interaction that you actually have is being able to take photos of the characters.”

Expansive, multi-level expressions emerge through art/video game projects such as multimedia artist Lawrence Lek’s sleek collaboration with electronic musician Kode9, Notel (2017), or Scott Snibbe’s playable “app suite” for Bjork’s Biophilia album (2011).

“There’s this ongoing question of whether video games are ‘art’; certainly, a large element is design and process”

Elsewhere, the retro visuals of early video games continue to provide creative inspiration – including Brighton-based David Blandy, whose Duels And Dualities installation (2011) demonstrates his love of early-‘90s arcade classic Street Fighter II, replete with self-styled “special moves”. Brooklyn post-conceptual artist Cory Arcangel has modified video games for some of his most famous works, including 2002’s dreamy Super Mario Clouds and the pop culture blast I Shot Andy Warhol, and the agonising “gutter ball” loops of Various Self Playing Bowling Games (2011). “My real experience with video games was watching other people play,” Arcangel tells Mary Heilmann in Interview magazine. “That’s why a lot of my work isn’t really about playing. It’s about watching video games.”

Splatoon © 2015 Nintendo

Milton-Polley points to the enduring pop art appeal of “retro” video game visuals: “These early visuals are simple but so expressive and easy to grasp,” he says. “It also demonstrates the chain of inspiration that comes with each generation of developers.” He notes how nostalgic visuals merge with cutting-edge tech in indie game stand-outs such as Cuphead (2017): “In Cuphead, the gameplay is a throwback to 16bit platform action, but it uses 20th century animation as its aesthetic – in particular, it’s a homage to the Fleischer Brothers – it has fluid movement, and these huge screen-filling bosses that loom over your character. It’s this magical hand-drawn animation that still feels like a video game, and it taps back into that childhood fantasy of playing the cartoon you were watching.”

Videogame/concept artist Nick Foreman is based at Sumo Digital in Sheffield, not far from the newly opened National Videogame Museum. He happily admits that his steely, ethereal designs (mostly created with Photoshop, 3D Studio Max, and KeyShot rendering software) stem from his own childhood fascinations: “I do love sci-fi, robots, hard surface design,” he says. “It’s a really strange feeling, to be able to control something in a game you’ve designed. People are experiencing your work in a very different way to looking at a print or just staring at a screen.”

The most powerful video game art does make you want to linger. Netherlands-based “next-gen art gallery” Cook & Becker deals in fine art prints from classic video games such as Bioshock (what co-founder Maarten Brands describes as “a press and pause approach to games that have had a big cultural impact”) and curates museum exhibitions.

“The video games which have had the greatest artistic impact have made me die a lot in-game,” laughs Foreman. “Because you’re looking at the game world rather than dodging bullets. The lighting in The Last Of Us is so amazing: the way it comes through a window or filters through foliage. The visuals look so beautiful, you want to spend time in them.”

Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt

At the V&A 8 September 2018 to 24 February 2019