‘By choosing to write in the first person, I am laying myself open to criticism,’ writes Annie Ernaux in Exteriors (2021). ‘The third person – he/she – is always somebody else, free to do whatever they choose. ‘I’ refers to oneself, the reader, and it is inconceivable, or unthinkable[.] ‘I’ shames the reader.’

Of late, autofiction has become both a much contested and revered term within the arts. At once the term seems to be imbued with a certain cultural cachet symptomatic of our current literary epoch, the objective ‘truth’ buried behind indecipherable layers of metatextuality. This, of course, is precisely the skill of the great autofiction novel – hailed as the new vanguard of literature, these works are meticulously assembled to obscure reality and fiction. As Celine Nguyen notes on Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (2024), ‘autofiction, done well, disguises its own artificiality.’ But, as some may suggest, the ostensible individualism of autofiction is as much a deterrent to the genre as it is a draw. ‘Sometimes I think people who write autofiction are narcissists,’ writes Joanna Biggs on Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School (2019), ‘[b]ut I know for sure, because I am one, that people who read autofiction are narcissists.’ I’ve previously encountered far less favourable criticism that also dismissed autofiction as lazy, self-indulgent, and/or egregiously confessional, so it’s of little surprise then that Ernaux and Heti would try to distance themselves from the label altogether – even if it does serve as a useful shorthand to explain what their work is doing.

By virtue of its dense form, the novel makes the most sense as an expressive medium for autofiction – but that’s not to say that this assiduous mode of self-construction is entirely absent in visual art. A conduit between word and image, the ongoing Maison Européenne de la Photographie exhibition Exteriors reconfigures Ernaux’s observations of everyday lives into photography. Transport serves as a central site for Ernaux’s surveying as it does the artists; Gianni Berengo Gardin captures Venetian commuters on a vaporetto while Harry Callahan’s images of residents moving around Aix-en-Provence. Public spaces, as Martine Franck, Ihei Kimura, Janine Niépce, Issei Suda, Johan van der Keuken, and Bernard Pierre Wolff probe, affirm gender and class hierarchies. But as is evident, Ernaux is not the subject of this particular show – curator Lou Stoppard’s interest is instead situated in our own response to the external, and what this may say about us as readers and viewers. ‘It is other people,’ Ernaux writes, ‘anonymous figures, glimpsed in the Metro or in waiting rooms – who revive our memory and reveal our true selves through the interest, the anger or the shame that they send rippling through us.’

As Ernaux writes towards a transpersonal ‘I’, other visual autofictions take a radically different approach. In Art Monsters (2023), Lauren Elkin makes the case for the political subversiveness of the ‘I’ in art made by women. Irreducible to any universal meaning, she positions first-person art as a deliberately obstructive and transgressive feminist act. Further to this, Adam Thirlwell writes that this is the kind of art that is ‘deliberately excessive, oversharing, overintense, something that refuses to follow some law commanding separation of character and creator.’

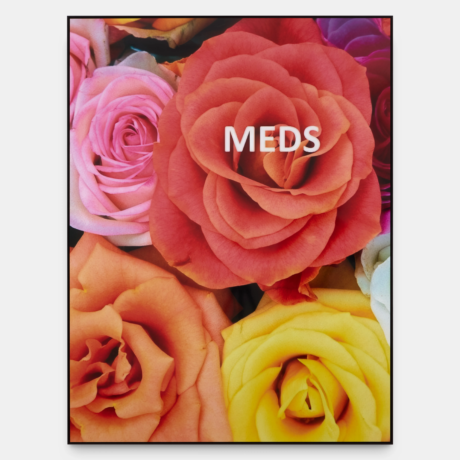

Tracey Emin’s work testifies to this very idea – to bear witness to it feels almost like an act of invasion, no matter how public its display may be. My Bed (1999) remains one of the most controversial artworks ever made with its assortment of vodka bottles, cigarettes, pill packets, used condoms, and a pregnancy test. (At the time of its debut, Adrian Searle dismissed the piece as an ‘endlessly solipsistic, self-regarding homage.’) Her 2019 exhibition, A Fortnight of Tears, at White Cube Bermondsey was just as brutal and unsettling. Chronicling her experiences with rape and a botched abortion, the show retells these events through a variety of mediums and forms: sculptures, paintings, and neon lights. Coming a full 25 years after Emin’s original abortion film, How It Feels (1996), the artist plays with temporality and narrative construction to explore the evolving impact that the event had on her. In doing so, she moves towards an entirely new set of ideas: ageing, death, and her ever-changing relationship with the body.

Like Emin, Louise Bourgeois is another artist well known for revisiting early traumas throughout her extensive body of work. Her Cells (Eyes and Mirrors) (1989-93) series functions as theatrical spaces to contain and release her autobiographical archive. Here the cells present fragmented images, portraying secret histories of pain and desire; the curated angles reveal unravelling versions of the self through staged objects. Elsewhere, Bourgeois’ Red Room (Child) and (Parents) (both 1994) feature a pair of hands – one child’s and one adult’s – evoking the subjects’ longing for security, a desire further underscored by two mittens embroidered with ‘moi’ and ‘toi’. As Bourgeois’ rich and multi-layered relationship with psychoanalysis proved to be fertile ground for her art, her work too can be read as an attempt to retrospectively exorcise the pain of her childhood.

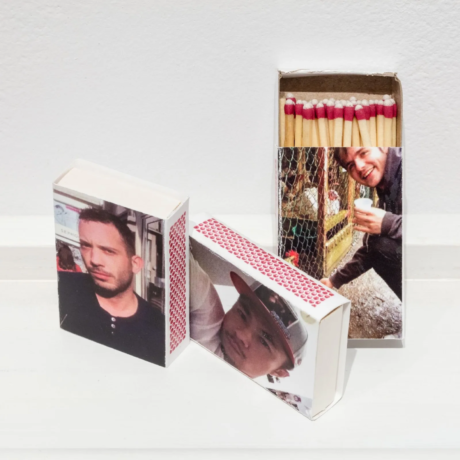

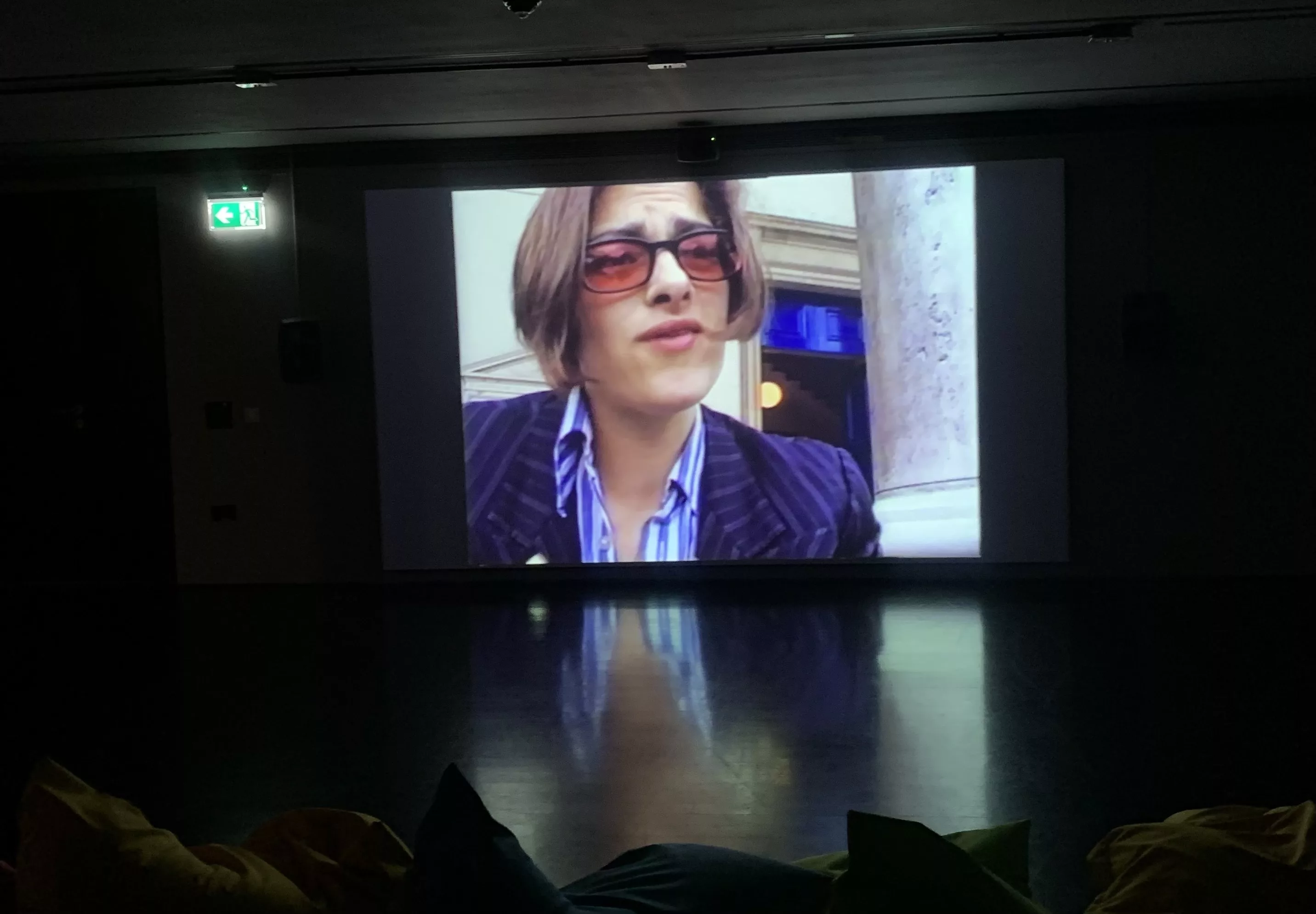

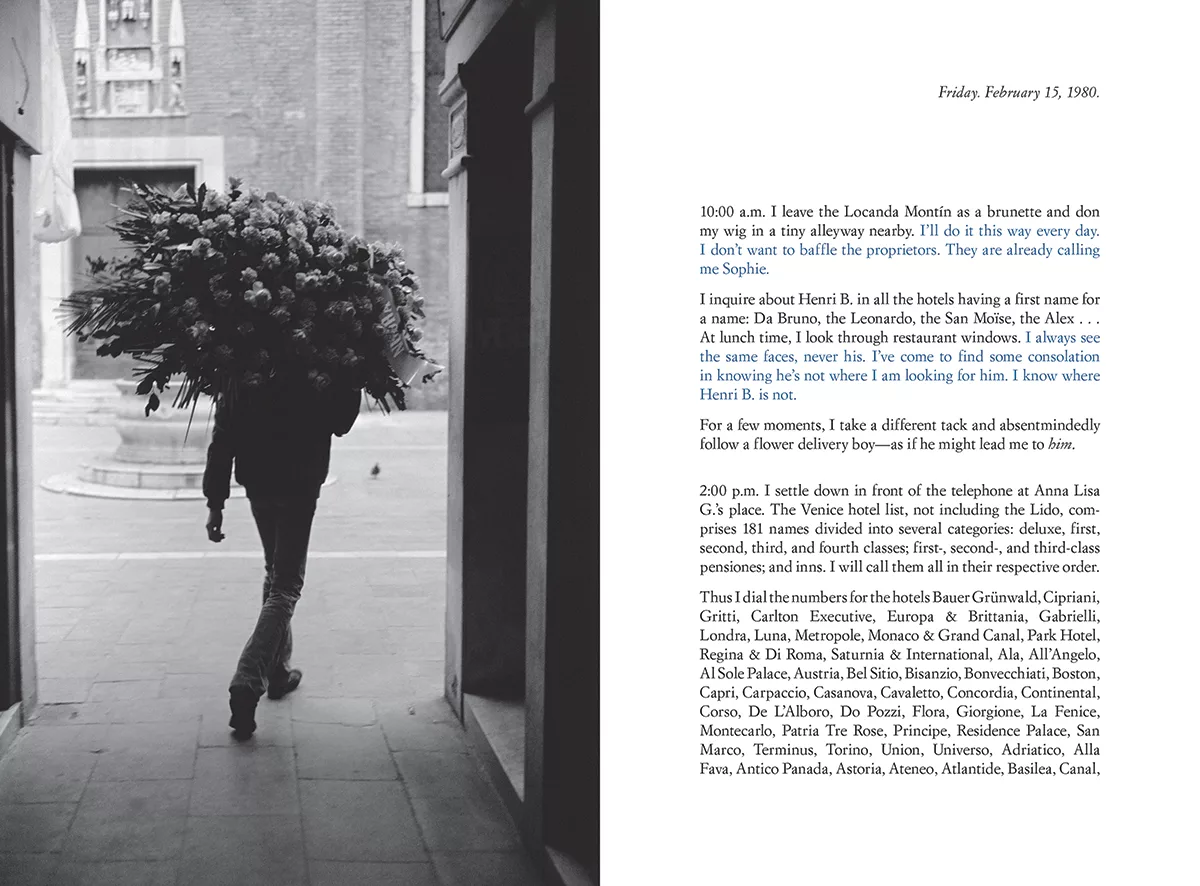

If Emin and Bourgeois’ art excavates and reconstructs their memories decades later, French conceptual artist Sophie Calle assembles an entirely new narrative strategy for blurring fact and fiction. Her autofiction projects involve imaging scenarios in which she herself is implicated, recording these through photographs and diary entries. Of these, Suite Vénitienne, her 1983 book, is perhaps the most absorbing of her works. Chronicling her pursuit of a man named Henri B. in Venice, Calle meticulously documents her efforts to track him down by employing a forensic-style archive which culminates in a tense confrontation between artist and subject. The result is an adept exploration of distance, absence, voyeurism, and exhibitionism – real life desecrated in favour of the artful composition of self. Although there is certainly an autobiographical dimension to her work, these images are just that: stills from a rich and complex life. So, to take Calle’s art at face value is to dismiss the entire point of her work and the creative processes which go into fictionalising and constructing.

Heti’s Oulipo-esque Alphabetical Diaries, by contrast, feels decidedly more reserved. As does Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy (2014-18) with its focus, like Ernaux and Stoppard’s Exteriors, turned towards the strangers she encounters on her travels. But much like Emin, Bourgeois, and Calle, these are all writers who’ve also faced accusations of oversharing, of their work being ‘too much’ for public consumption. (Calle’s forthcoming retrospective at The Walker Art Centre is literally titled Overshare). Collectively, their work anatomises experiences of obsession, death, abortion, infidelity, illness, and sexual violence – all subjects that, by societal standards, should be kept private or at least veiled through the guise of fiction. Rachel Sykes argues that these anti-oversharing indictments are innately gendered: those who reveal too much of themselves – particularly that which is sexual or bodily – fall outside of patriarchal norms. ‘To label an expression an overshare and a person an oversharer is an effort to reestablish a context,’ she says, ‘to refocus the blurred lines of real and virtual identities, and to posit the offending expression as inappropriate.’

Autofiction writers Lerner and Karl Ove Knausgård – whose obsession with writing about faecal matter I’ve only recently learned about – rarely face such scathing accusations, despite writing at length about their own psyches, bodies and sexuality. In a Telegraph article last year, Lerner himself pointed out that male writers are rarely asked about having kids – meanwhile, the question of motherhood feels inextricable from the conversation of women and art. And save Salmon Toor, few confessional male artists spring to mind in the way Emin or Bourgeois does.

Perhaps, then, the obtrusiveness of this feminist art-making and aesthetic self-construction is exactly the point. In I Love Dick, Chris Kraus invites the question: ‘[W]hy not universalise the “personal” and make it the subject of our art?’ and to this, I ask: What good is art that is trying too hard to be ‘for everyone’? One of the reasons autofictional art works so well is that it goes against the flattening of women’s lives into palatable narratives by centring discomfort. In particular, Emin’s art, as uncomfortable a viewing experience as it may be, ignited global conversations about mental health, reproductive and sexual justice. Had her work been diluted or censored in any way, then maybe it wouldn’t have been as effective. In any case, male artists and writers haven’t needed to lay themselves as bare precisely because of their proximity to power – the brilliance of feminist autofiction lies in its potential to reclaim it.

Written by Katie Tobin