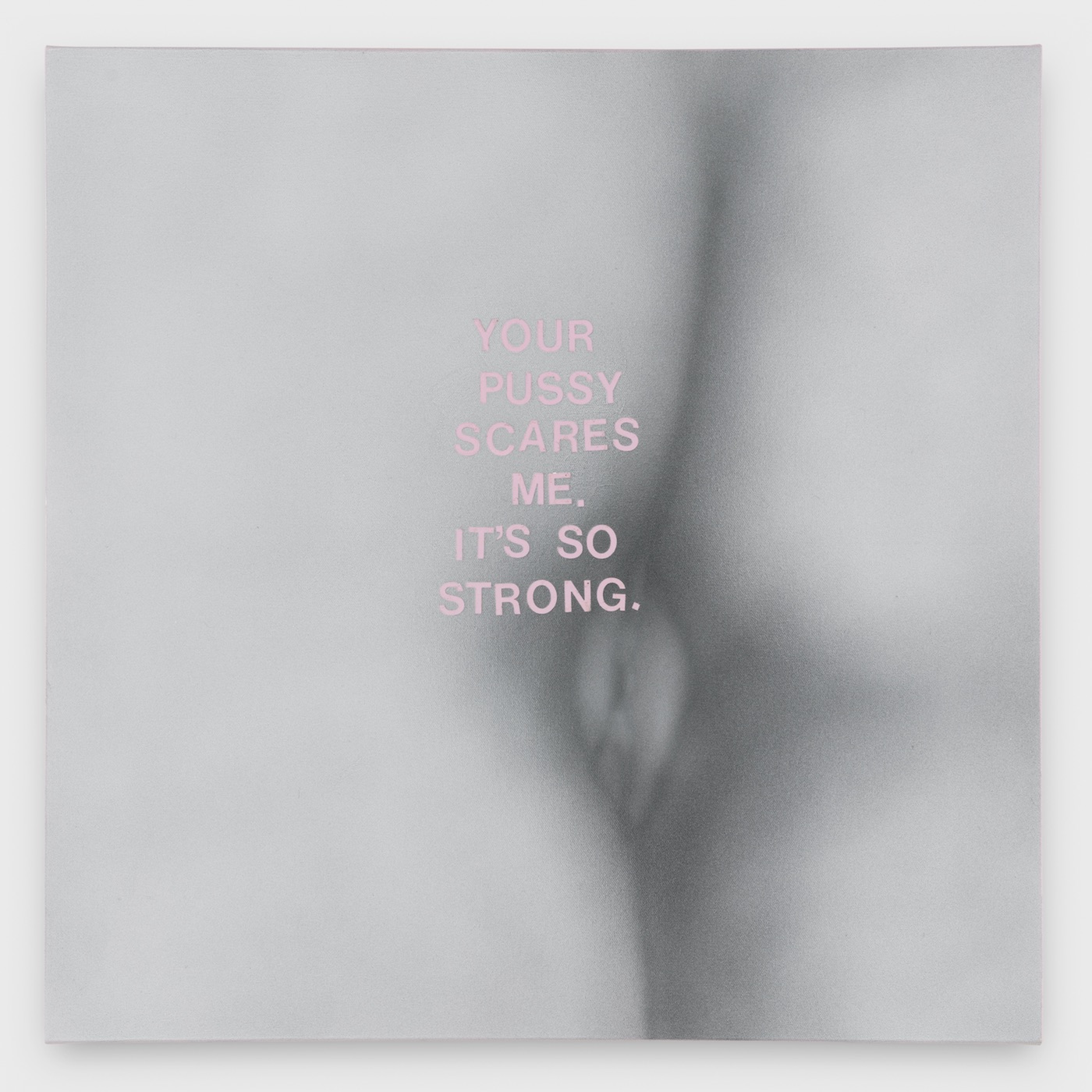

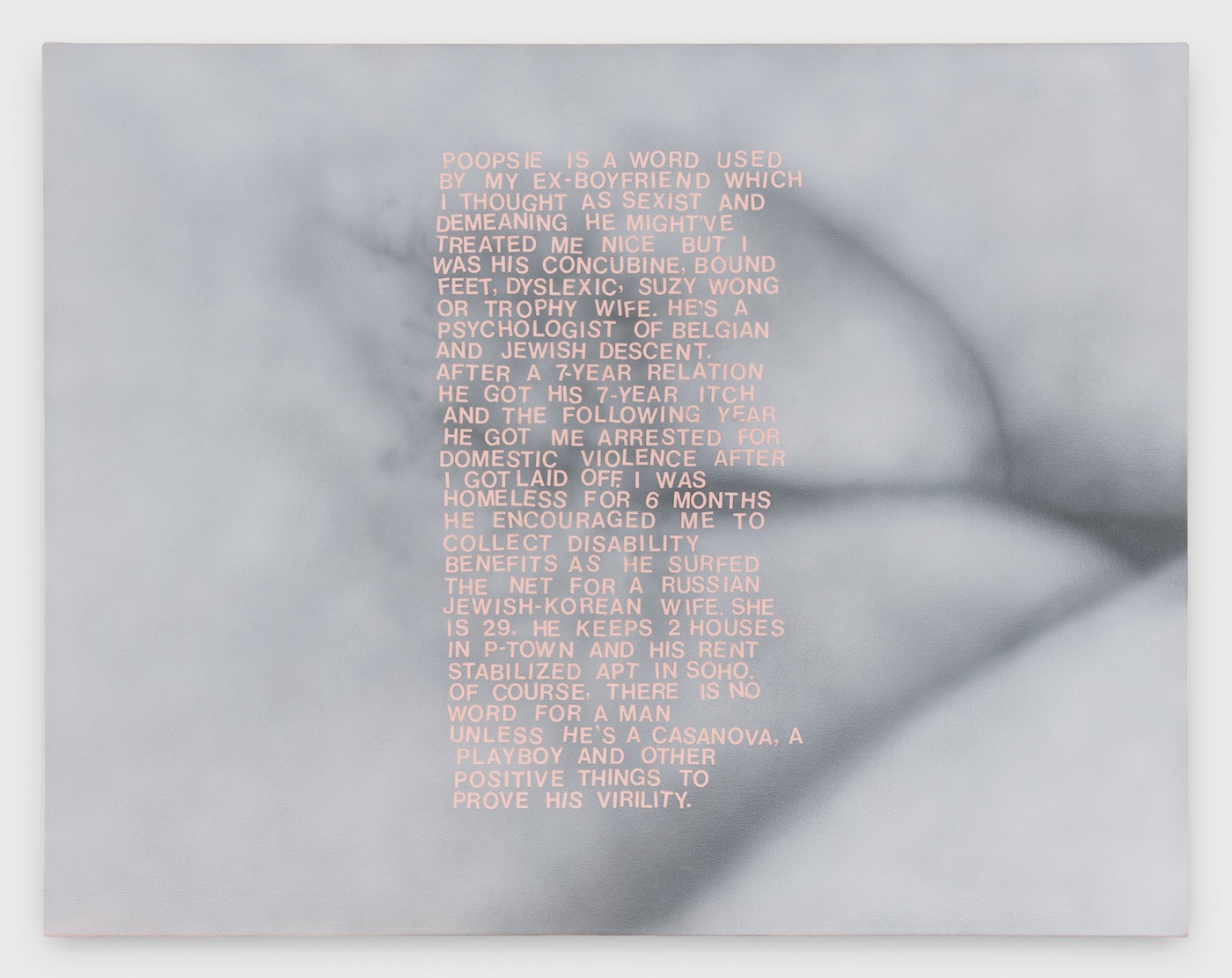

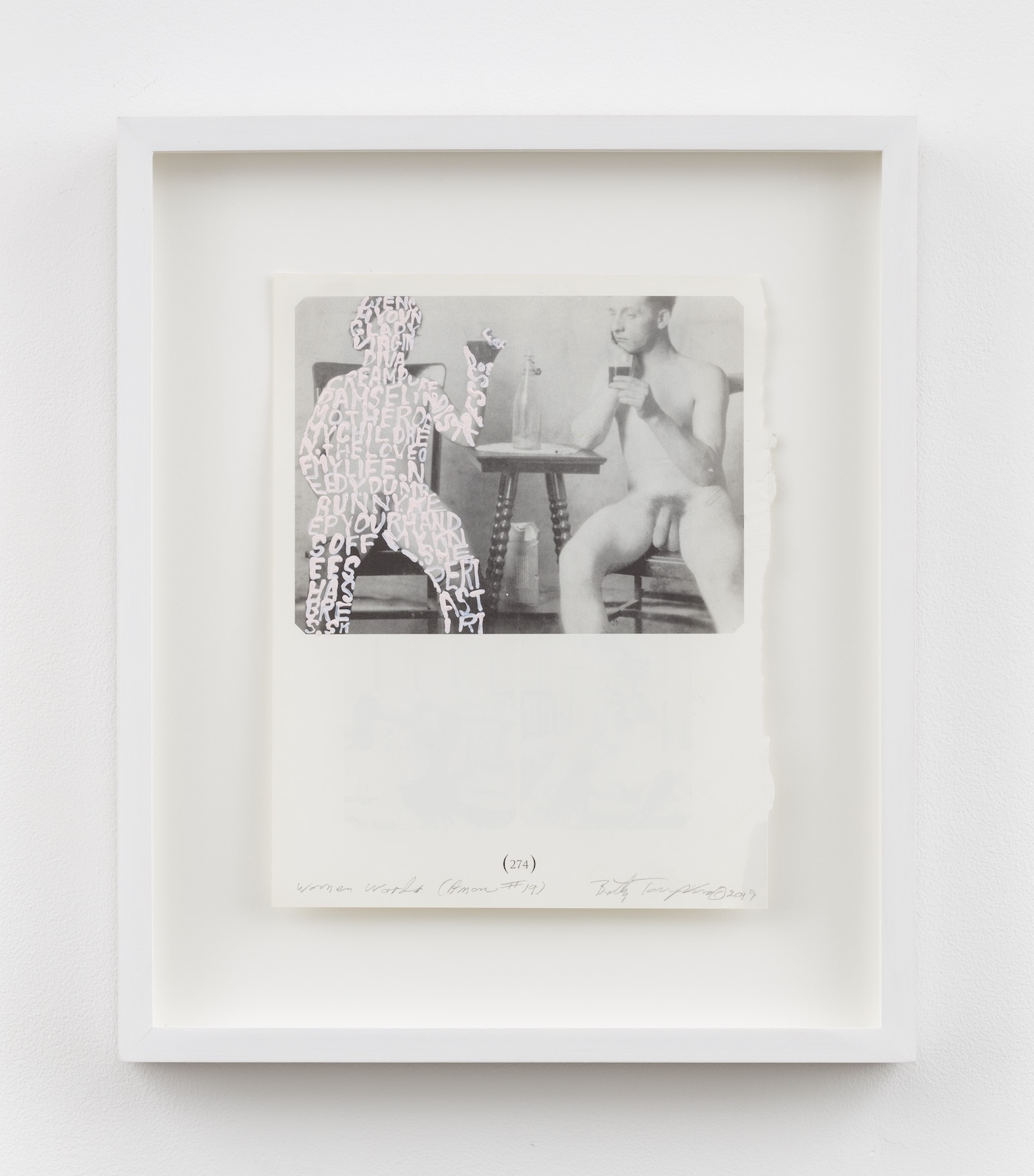

The last time I interviewed Betty Tompkins she was busy angrily cutting up art history books. The results of that destruction are now on view at P.P.O.W gallery in New York: a new body that adds to the ever-expanding Women Words project Tompkins originally began back in 2002, soliciting anonymous contributions from the public, her comeback moment. The latest Women Words are taken from response cards deposited at her last Women Words exhibitions in Miami and New York, eye-wateringly crude, often violent, misogynistic and sexually explicit language, painted in pink over the female figures in canonical works of art torn from the pages of art history books and art magazines. A similar-looking series, Apologia, applies the same technique, but dissects the words issued in the flood of verbatim apologies—those issued by Chuck Close, R Kelly, Jens Hoffmann, Mario Batali, among them—in response to #MeToo accusations made by women.

This year has been a maelstrom and this exhibition at PPOW seems to be a very direct response?

This exhibition pulls together the beginning of my work with language (the LAW pieces) from the 1970s and eighties with what I am doing with language now (the Women Words and Apologias) on the pages of art history and photography books and the Insults and Laments on canvas. I started the work in this show during the summer of 2017 when I finally opened the packages of audience response cards from Flag Art Foundation and Gavlak Gallery in LA. A lot of them were worse than the ones I had been emailed, so of course I wanted to work with them. In 2013 I had done three pieces of pages torn from a Taschen book called Wheels and Curves. I had shown them once then and then developed the 1000 Women Words into paintings on small canvases instead. There being only so many hours in the day, even though the three were hanging in my studio, I forgot all about them. I started to look at them very intently after I saw the response cards.

Looking at art books like Wheels and Curves—and other texts on the art world and art history—what was it that made you want to work with the images?

One of them struck me as totally creepy—the photo shows a car, a man peeking behind a tree staring at a half-dressed woman. I really wanted to go there again. The woman is covered with the language that society uses to define her. On one of the three, you can see the woman but she is surrounded by this language. So I started there, concentrating on photographers—Weegee, Brassài, Helmut Newton. At a certain point, I moved the idea onto pages ripped from art history books, which has opened up everything to me. As I was doing them, the #MeToo movement was gathering steam, and every day I was (am) getting material from the news and from magazines and blogs. And then came the Apologias which were codified so fast, I wondered if they were all being written by the same lawyer. So I started with leftover words and phrases and developed from there to current events. Never until now has an idea I am interested in been in sync with what is actually happening in the world.

The exhibition also features works you made in the seventies and eighties, quite different times. How do you look at those works now and how do audiences respond to them now, compared to back then?

The LAW pieces form the basis of the show. I hope that viewers will start to see how I have used language and image from the beginning. They have not been shown for almost forty years. I made them after reading an article in the seventies that high school and college students did not recognize the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. That bothered me a lot so I did them. When I was in elementary school, everyone went on a school trip to DC to see them. I don’t know if that happens anymore. Do people know their rights and the history of them? The Constitution and the Bill of Rights should be known by everyone. Our government is run according to them.

My work has often been described as “ahead of its time”. I think you can only be in your time and not ahead of it but your time can reject you. There is no obligation for your time to accept what you are doing.

What needs to change in the art world and how can we change it?

I have learned that women have good cause to be enraged and triggered and men, in general, continue to feel entitled. It may take many generations for this to change if it does at all. The call for diversity is so strong now, some little bit may finally happen.

People didn’t always want to listen to what you’ve had to say. Will you ever shut up?

No! A painting I am planning came from my first report card in the first grade: Betty would be a better student if she didn’t talk so much.