Writer Katie Tobin explores the many ways artists contend with the natural disasters and tragedies facing our world, calling on the words of famous critics like Maggie Nelson and Paul B. Preciado to assist her.

Against my better judgement, I’ve been thinking a lot about art and the end of the world lately. This, no doubt, has probably been brought about by the recent spate of exhibitions fixating on our impending ecological collapse through a particular lens of environmental nihilism. Hayward Gallery’s Dear Earth and Back to Earth at the Serpentine were two such shows, more concerned with pithy sloganeering and patronising gallery-goers than they were with exploring art’s role in ecological intervention. But speculative art—for all its latent fear mongering—must also point towards a hope for salvation. As philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado observes, ‘A work of art is not a work of art if it cannot be destroyed, and therefore be fantasised and imagined—it can’t exist in the immaterial museum of longing and desire, if its loss doesn’t justify intense grief.’ Art alone will not save us from the apocalypse, but good art may remind us of what we stand to lose.

A recurring theme in cultural critic Maggie Nelson’s latest, Like Love, is the purpose of art in times of crisis. A corpus of profiles, conversations, reviews, essays, and criticism, this idea of art’s potential power for political efficacy runs deep throughout; ‘Can art offer something other than stylized despair?’ Nelson asks in one such essay. In the same piece, she also tells us that facing climate change, ‘one of the things we can do, for better or worse, is make art.’ But whether art holds the potential to affect the change she/we hope to see in the world isn’t always clear to Nelson or her readers. ‘As we struggle to figure out how to notch back the degrees, so as to mitigate the suffering that a warming planet is going to bring, we also need to figure out forms of relationality—both to ourselves and to each other—that won’t make things worse,’ she writes. How art might go about doing this, is a different question altogether.

Ideas of radical intimacy and family abolition have slowly gained traction within creative spheres over the past few years. This was no doubt catalysed by the reappraisal of the bourgeois, nuclear family during the pandemic—which to many, myself included, marked the end of the world as we knew it—when policies assumed that this domestic set-up was the norm for most. As the lockdown continued, the social need for community and kinship beyond the remit of the nuclear family grew progressively more urgent. And, like Nelson, artists have also since been toying with similar ideas about art’s role in articulating these new ‘forms of relationality’.

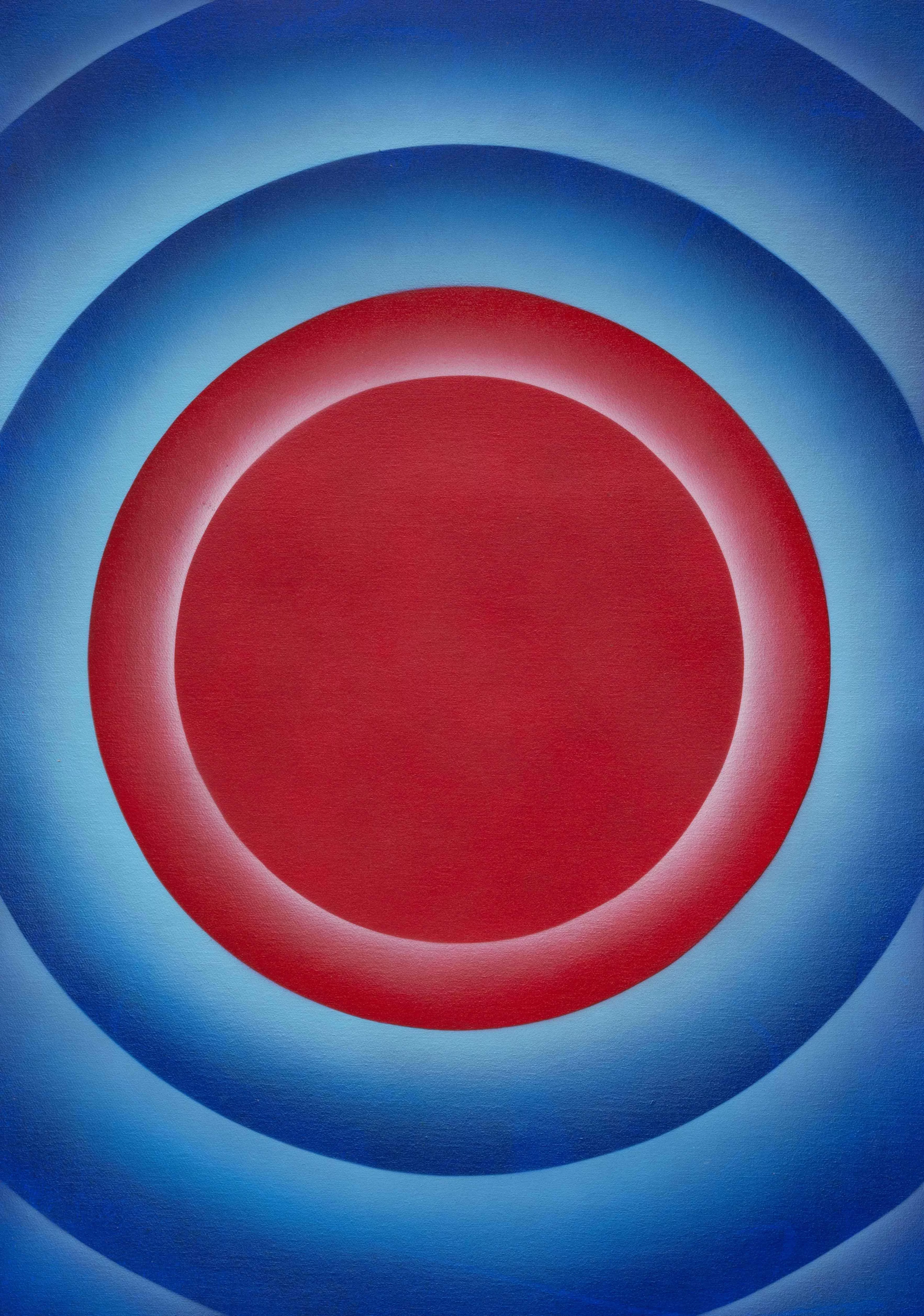

It’s with this idea that Gray Wielebinski transformed London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts into a nuclear bunker of sorts late last year. Inspired by an essay from queer sci-fi author Samuel R. Delany, The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low was situated between Buckingham Palace and Whitehall; Wielebinski envisioned the transformed space as a response to the protection granted to institutional powers—powers that may well bring about the end of the world as we know it. His bunker was the stuff of Silicon Valley billionaires and apocalypse fantasists. ‘In its privacy, surveillance, and exclusivity, the bunker also speaks the language of illicit spaces—another kind of world within a world,’ the artist says of his work, ‘where separating oneself leads towards community formation rather than isolation.’ Through meticulous curation, the show literally forced people together: viewers could sit in a conversation pit shaped like a radioactive symbol, or play a game with no clear rules. It’s here that Wielebinski’s show fosters a new kind of intimacy, buried somewhere amongst the pre-apocalyptic tension of late capitalism, the aftermath of the pandemic, and climate change in the world as we know it. All of this points towards the people we choose to be with, the communities we choose in crisis; as Wielebinski puts it, ‘There are other forms of survival and bonding.’

Judy Chicago’s Revelations tries to compel a similar response from viewers—this time, through an explicitly Biblical and ecological reading of the apocalypse. Like Wielebinski, Chicago argues that crisis compels care; in the ‘Visions of the Apocalypse’ section, her intricate drawings and collages depict an apocalyptic scene between men and women, leading to the profound revelation that everyone can live ‘harmony with each other and the Earth’. What If Women Ruled the World? (2022), a quilt made in collaboration with Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova, is also a piece that boldly—if a little naïvely—imagines an alternative social order and a world governed by compassion, empathy, and femininity. Chicago’s The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2012–2018) series, shows the flora and fauna under threat of extinction: polar bears, turtles, orchids, and many more.

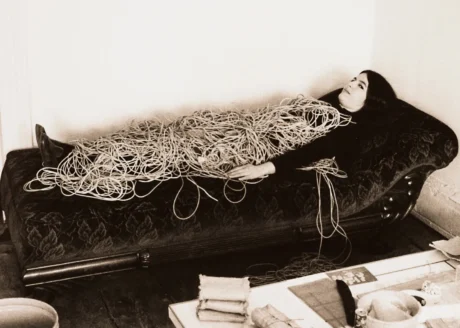

The show’s achievement lies not in Chicago’s attempts to be overtly didactic, but in her vibrant, celebratory embrace of life, womanhood, and the Earth, channelling her trademark excess into something profoundly joyful and empowering. (As Laura Cumming puts it, ‘When the script appears white on black, like chalk on a board, it looks uncomfortably like the lesson it so often is, banging on about ecological disasters’.) Commissioned by Greenpeace, her Rainbow Warrior (1980) is just this, inspired by the Native American legend of the same name. Her Atmospheres (1968–) performance series centres women as goddess-like figures in the Californian desert, enveloped by eruptions of colour, smoke merging ‘with the wind, the air and the sky’.

What Chicago’s retrospective could have benefitted from is an emphasis on the potential for artistic practices as climate intervention and activism. Agnes Denes’ Wheatfield: a Confrontation (1982) turned a vacant Manhattan lot into a thriving wheatfield to highlight urbanisation’s ecological impact and the importance of sustainable coexistence. (At this year’s Art Basel, a homage to the work was installed in the city’s central Messeplatz.) Another artist working along these lines is Saskia Van Imhoff. Integrating her roles as both farmer and artist, she repurposes materials sourced from her rural Dutch plot to create studies of cultural heritage and advocate for environmental stewardship. A new exhibition at Incubator, appropriately titled Utopia, aims to also redefine the role of art in environmental advocacy. Partnering with ClientEarth—an environmental charity that leverages legal strategies to drive systemic change—the show sees artists’ innovatively use materials like natural pigment paintings and copper plate etchings for their work qua Incubator’s ‘leave no trace’ philosophy. Together these artistic practices feel like a testament to what art can do, offering a more rigorous approach towards environmental activism within the artworld.

The artistic obsession with the apocalypse is nothing new, of course—just look at JMW Turner’s dramatic scenes: blazing sunsets over battlefields, ships burning and sinking. But it seems this latest wave of artists have taken to using their work as praxis. Recalling Nelson’s essay, their work emphasises our connection not only to the Earth itself but to one another, and how this might inspire tender acts of communal care during crisis. Looking at things this way may well help us resist the impulse to succumb to total nihilism. After all, art is so much more than mere stylised despair.

Words by Katie Tobin