What makes for successful comedy in art? If there were rules, it wouldn’t work, but the key may be that surprise or incongruity leads to a recognition that there are deeper issues to dig into under the surface of the joke. That may, of course, bring in disturbing or melancholy aspects: Richard Prince rubs the punchline in just a bit too hard; Bruce Nauman is one of many artists to edgily play out the cliché of the sadness behind the clown’s mask. Here are some recent examples of works that lure us in with humour but then reverberate with psychological, environmental, economic or social concerns.

“The sexual and scatological are perfectly unrespectable zones for art humour”

Dana Schutz, Boy with Bubble, 2015

Dana Schutz’s characters tend to seem stuck between composition and decomposition as they attempt the absurd, such as eating their own faces. They’re funny, yes, but troubling. Here she wittily rhymes all sorts of circles, including a bubble-headed Lederhosen lad, and sets them against the angularities of the Alps. Is that a smile or just a concentrating tongue as he anticipates popping the bubble? Does art, we might wonder, transform the surroundings or merely reflect its creator? And either way, how long will it—or we—last?

James Hopkins, Scaled Ladder, 2014

James Hopkins presents an implausible object, its spindly wooden slats bearing heavy rocks to no apparent purpose. We’re tempted to seek a logic. Have the small rocks risen because they weigh less? It can’t be that, their density’s the same. Is it that the relative mass of a mountain as you climb it is echoed by the stones’ sizes as we imagine ascending the ladder? Meantime, the title puns on “scale” as the act of climbing a summit, a fundamental concept of sculpture, and a reference to the diminishing size of the stones—and that brings out the resemblance to an abacus.

Paola Pivi, Bad Idea, 2017

Italian artist Paola Pivi is best known for working directly with live animals, putting ostriches, zebras and donkeys in surprising, yet un-Photoshopped, situations. Her full-size bears surprise differently: they act in a far from ursine manner, and are made of feathers, absurdly parodying the possibility of flight and, perhaps, idealists who talk up how “you can be whatever you want to be”. Recent examples take the surreal turn a stage further by sporting neon colours and bearing light-hearted titles.

Sarah Anne Johnson, Uck, 2015

It’s not easy to be funny about the environment, so credit to Canadian photographer Sarah Anne Johnson: what seems at first like an immature, if still amusing fallen-letter gag turns out to incorporate a protest against immature thinking that betrumps nature. The addition of real glitter ties Uck into her series Field Trip, in which she alters her images with paint and digital tools to revisit the psychedelic colours of the idealistic hedonism of her own festival-going youth through a nostalgic yet more knowing lens.

Christian Jankowski, Massage Masters (Promise), 2017

Christian Jankowski has a way with public statues as part of his wider strategy of playing people outside the art world into his multimedia productions. For Heavy Weight History, he challenged powerlifters to raise statues of the great and the bad, a light-hearted way of engaging with such burdens on history as Stalin and Reagan. Now, he has recruited masseurs to optimize the wellbeing and, who knows, maybe in consequence the communicative effect of stone figures around the streets of Yokahama. When he screened his film of the event, viewers in turn received massages, surely rather wasted on flesh.

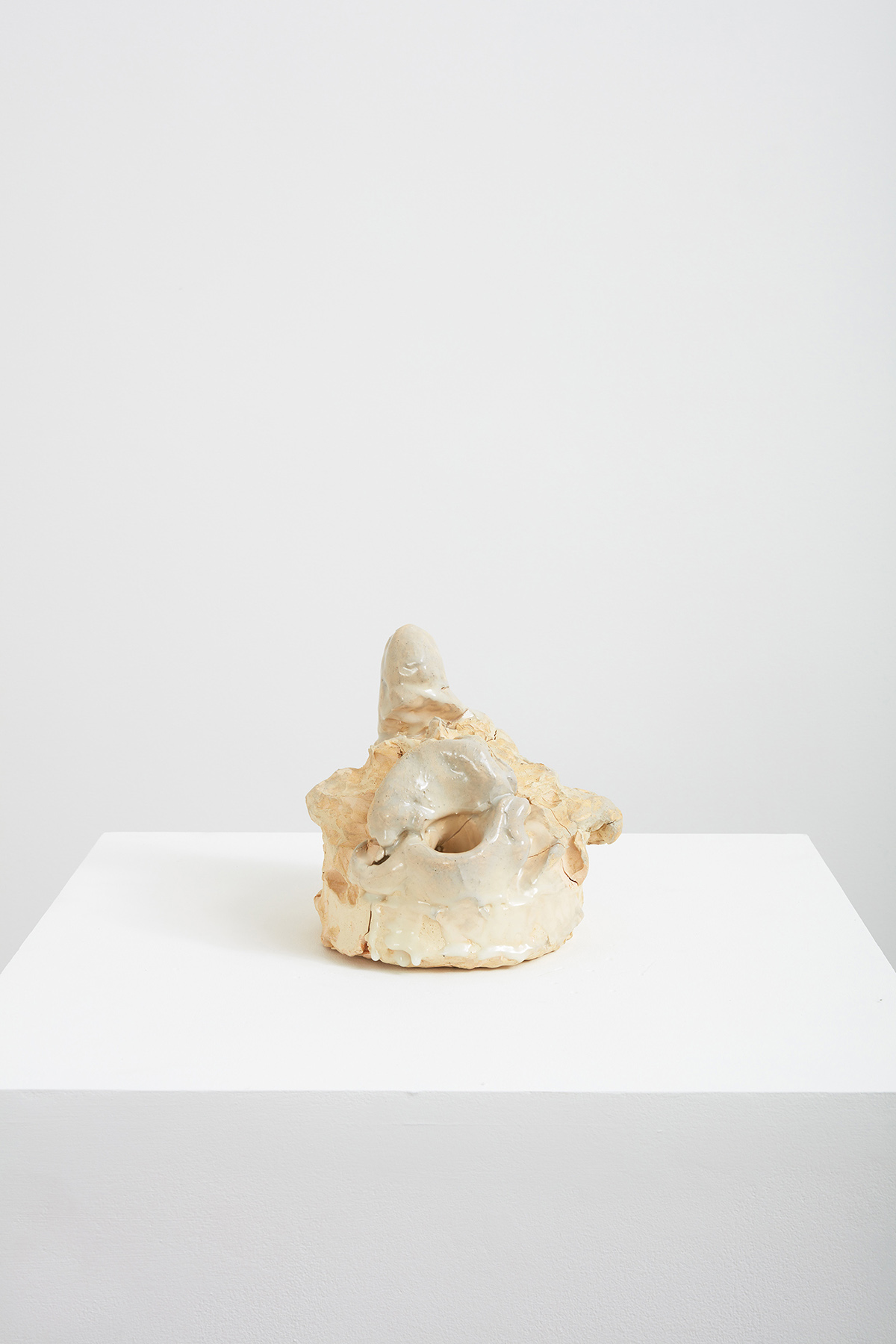

Gelitin, Golem, 2015

The sexual and scatological are perfectly unrespectable zones for art humour, and Gelitin are often found there. That said, their series of Golems seem innocent enough—until you see the film of them being made in what the Austrian collective term “an oneiric ritual to unhinge their primordial spirits” for which, in their gallery’s deadpan words, “they immerse themselves in clay and model it using their own bodies as a medium”. Never mind the macho male artist metaphorically “painting with his penis”, or Henry Moore’s spatial use of holes, the film shows the four men literally fucking the forms into being.

John Smith, Steve Hates Fish, 2015

John Smith—that’s the John Smith, of course—has subversively exploited misunderstandings since his seminal The Girl Chewing Gum (1972). In Steve Hates Fish he scans signs with a translator app, having set his phone to convert French into English, causing the programme to thrash around hopelessly when faced with a London street. “Fruit & Vegetables” becomes “Profit Venerable” and “Current” rentals become “Surreal”, parodying the verbal clutter of the cityscape and challenging our instinct to make sense of it. And what could it mean, in the Brexit context, to see a Briton self-defeatingly misapply what comes from Europe?

This feature originally appeared in issue 33

BUY ISSUE 33