I have a membership card for an independent cinema in London. On the front of it is a horde of skeletal zombies with outfits and haircuts deeply embedded in the 1980’s. On the back is the declaration: THIS IS YOUR GOD. The imagery and text come from the John Carpenter film They Live (1988), a satire on consumerism in which the subliminal messages of advertising and capitalistic consumption are made clear: after a drifter named Nada finds a pair of supernatural sunglasses, he discovers that billboards carry with them a simple, overwhelming message: OBEY.

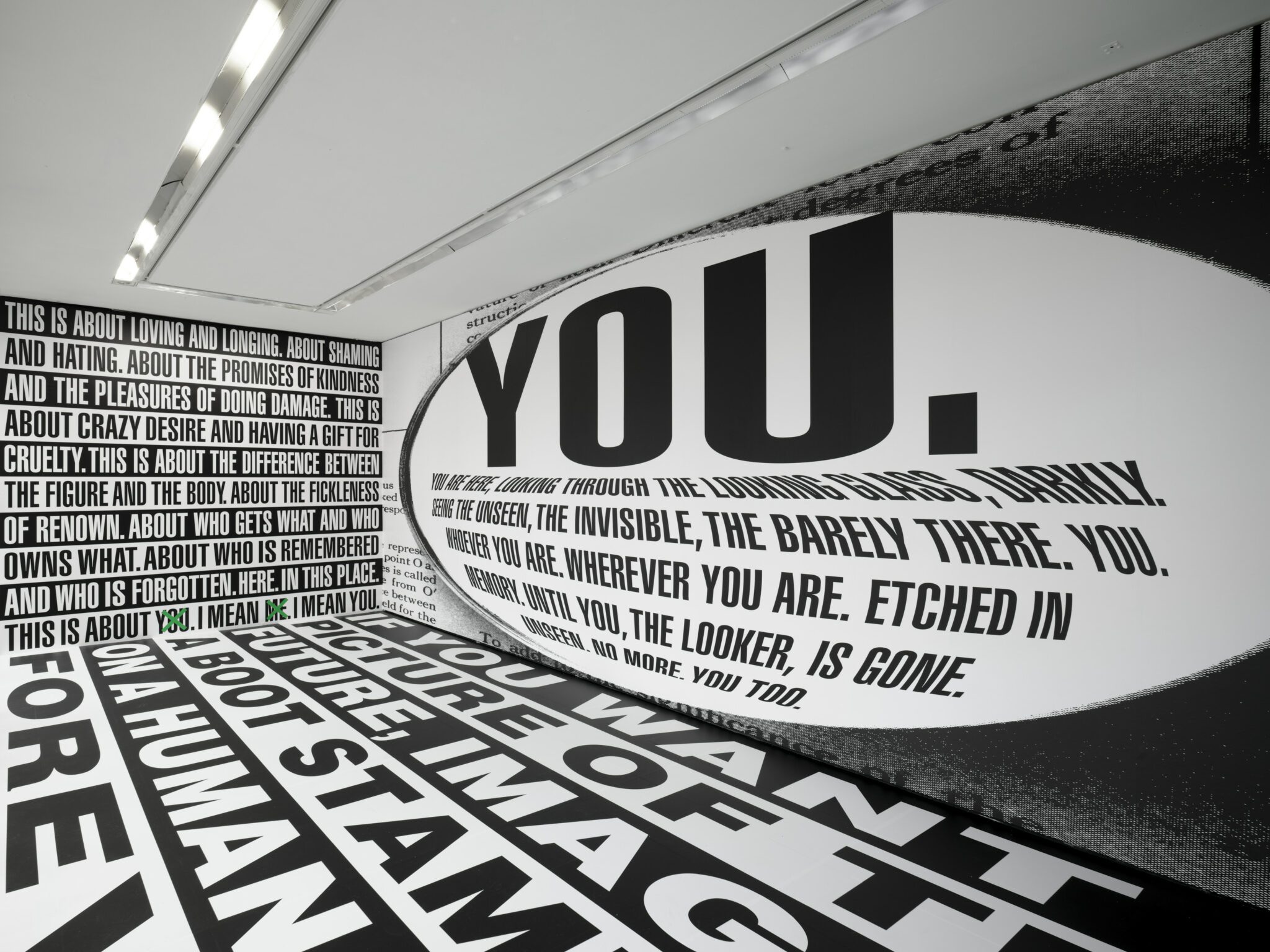

The power of the sunglasses sequences in They Live comes from the way Carpenter harnesses point of view shots, putting us behind the eyes of Nada, revealing the dark secrets of the world to the audience. Because of this, the sequences are in black and white; between these monochromatic backgrounds and the stark boldness of the text, They Live could exist side-by-side with the work of Barbara Kruger.

Through her use of image and text together, Kruger takes subliminal, subtextual ideas in advertising and mass media and renders them into text. The first room of Thinking of you. I mean me. I mean you presents walls of Kruger’s work together in a collage, with images that feature everything from groups of teenagers on their phones, to an image of a mushroom cloud put in morbid contrast with text that reads The Future is stupid. In this marriage of text and image, it’s as if Kruger has granted everyone Nada’s sunglasses from They Live, a chance to see what the world is like in all of its uncertainty, horror, and political violence. In manipulating images, Kruger shows just how easily we can be manipulated by them; one of the most striking examples throughout the exhibition sees Kruger using the Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photograph V-J Day in Times Square (1945), and offering it a complicated, somewhat chaotic caption. What’s supposed to read This will make my boyfriend jealous instead has those final two words crossed out, replacing them with nation relieved across the bottom of the image.

What Kruger’s work understands best is the sinister feedback loop of advertising and capitalism – particularly in an age where we’re increasingly online, and our data is readily available – as one of her collages declares: You are the product. But while there’s something nightmarish about this, it can also feel strangely seductive, the ultimate way to feed egos.

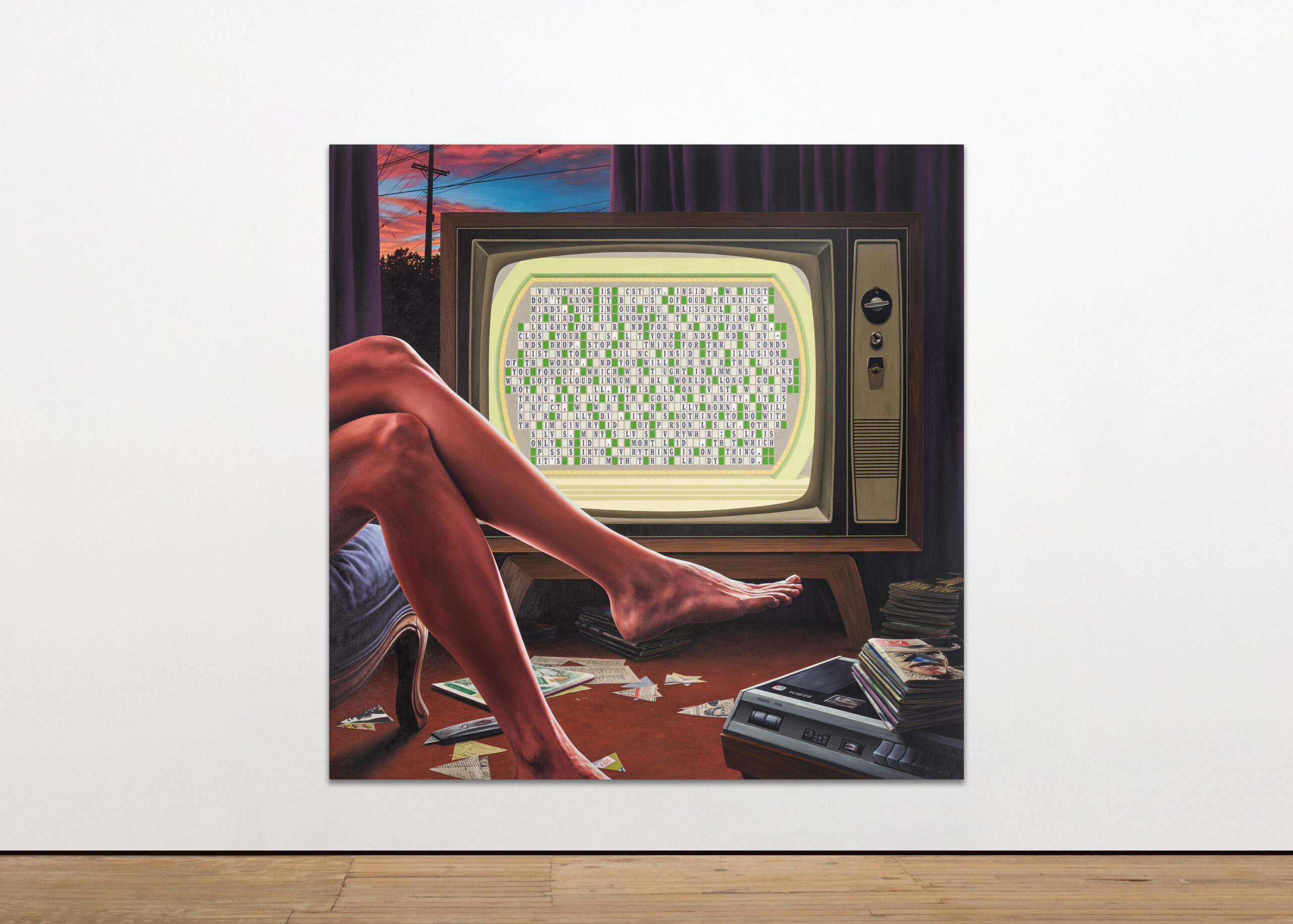

In Local Programming at GRIMM New York, Eric White understands just how seductive the glare of the TV screen can be. In his fascinating oil paintings, the TV functions like a mirror and fireplace all at once, illuminating the world for his subjects while reflecting their deepest desires – and even their sense of self – back at them. In i’d Like To Buy A Vowel (WHEEL OF FORTUNE), an immaculate image of the game show is placed in contract with a classic image of seduction taken right out of a James Bond film:a pair of long, bare legs, one crossed over the other. The question of exactly what it is that’s seductive here is left in the air – is it the leg, the game show, or both? – something that’s reflected in The Winner’s Circle ($10,000 PYRAMID), where a woman’s legs are in a similar pose but this time she’s sitting on the TV, legs dangling in front of the screen.

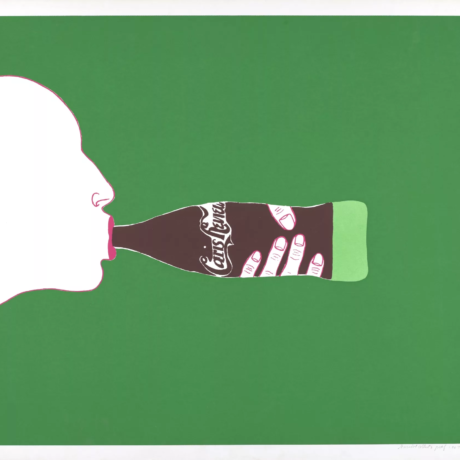

It’s in this relationship to the seductiveness of the image that Kruger and White are most starkly opposed to one another. While White grapples with what it means for the things that we’re sold – through game shows, magazines, ads – to be compelling and seductive, Kruger offers a more blunt, aggressive critique. Her image of Patrick Bateman, the eponymous American Psycho, as played by Christian Bale, in a raincoat talking about Huey Lewis and the News, with the caption Die Yuppie Scum! is incredibly revealing about the way her work relates not only to capitalism and consumption but satires of it: in Kruger’s work, all images seem to be equally evil.

Even Kruger’s own work isn’t safe from the artist’s critique. Whether it’s an image of Barbara Kruger Jenga, or images of her art on t-shirts or Instagram feeds, part of Thinking of you seems to show Kruger reckoning with her own work and legacy, as if wondering if she herself has become part of the problem. This means Kruger is reckoning with the internet and sometimes, her boomer is showing in this work – replacing I shop therefore I am with I Instagram therefore I am seems immediately smart but shallow on further examination, and there’s a cynicism about the connection granted by technology, rightly or wrongly. In contrast to this, White’s work is firmly rooted in an analogue era: one of TV guides and primetime game shows; of Dorris Day and Paul Lynde. It’s through this that White creates the idea of a kind of cursed media – as if the broadcasts, guides, and TV personalities themselves are somehow vessels for evil, in the same way that subliminal messages zombify the population in They Live.

There’s something inherently analogue about cursed media; in cosmic horror they’re always forgotten tomes, leather-bound and ancient. In Local Programming, the TV Guide becomes a kind of Necronomicon, the shapes cut out from the faces of celebrities on the covers offering a cult-like obsession and unease. Kruger functions in a similar way, manipulating the faces and bodies of her subjects in order to drive home the horrors of mass media. In one image, a distorted face that seems akin to Donald Trump is captioned, in block capitals: OBEY.

Both artists turn these apocalyptic media landscapes into something hypnotic; where the information overload of Krueger’s work is akin to doomscrolling, the detail in White’s painting invites us to get lost in his imagery, in the spell being cast by the TV itself. This echoes a sentiment from David Foster Wallace, the idea that we are alone, with images on a screen given to us by people who do not love us but want our money. Both artists, in their way, show us what we wish that love could look like even if, in the end, it inevitably manifests as a kind of hate.

For a deeply political, polemical artist, it’s striking that Thinking of you doesn’t offer a solution – if anything, Kruger seems to suggest that solutions are almost impossible. But if there is anything here – and in White’s work, and even in a film like They Live – it’s this almost desperate impulse towards the fact that we need to wake up. One image that recurs throughout Kruger’s art is Janet Leigh in Psycho, moments before she’s stabbed in the shower. Just looking at the image is enough to bring that harsh, blood-chilling scream to mind. Maybe that’s what Kruger’s work is above all else: a silent scream, an attempt not just to remind us of the way mass media can get under our skin, but to shed it.

Written by Sam Moore