After a period of emotional toil, writer Saam Niami reflects on the electrifying effects of seeing Henok Melkhamzer’s work on a trip to Sharjah in March of 2024.

I wonder if this has ever happened to you: you’re walking down the street—more than likely, a street you’ve walked hundreds or thousands of times before. You have your headphones on, or you’re looking at your phone, or maybe you’re engaged in a conversation in your head. You’re detached and disconnected from the world. Nothing could penetrate a thin, invisible layer of distance between yourself and the rest of the observable universe around you. You’re closed off; you may think it’s intentional, that it’s your choice to hide away, in plain sight, but whatever brought you to this state was far from personal preference.

Then you hear something, or you see something. Something breaks through the force field: a bird chirping, a child playing, neighbours laughing. Or, in my case, something happens that is almost impossible to ignore: the sun warms your face in a way that almost feels like it’s the first time you’ve been outside in years. The hair on your cheek stands up a little, just enough to penetrate the layer between yourself and the universe, creating a tunnel of pressure that instantly evaporates the barrier between yourself and your surroundings. You take your headphones off. You put your phone away. The conversation in your head silences. You stop and let your face slowly burn. You close your eyes. You take what must be your first deep breath in hours, maybe days. Blood rushes to your cheeks and forces your muscles to form a smile. This is what I felt when I saw Henok Melkamzer’s work at the Sharjah Art Museum in March of 2024.

Two days before I saw Melkamzer’s work, I was lying on my roof in Brooklyn. My eyes are closed. I’m facing the sun. I’m beginning to feel my face burn. I’m smiling. It was the first warm day in New York this year, right at the end of February. My film partner Justin sits on a fold-up chair next to me. Exactly one year ago, Justin and I released a film we made together about the New York fashion scene. He spent the rest of the year in Vegas shooting for Usher, and I spent the next six months on the most exciting series of projects I had ever had. Music videos. GQ Middle East. New York Times. About ten articles for the same magazine you’re reading right now.

However, at the beginning of October, the world changed. The news, the photos, the videos from Gaza shocked my entire system and I ended my run of projects completely shutting down and hiding away. My relationship with work and creating changed. I didn’t write anything for months. I had nothing to say, nothing that could make sense of what I was seeing. All I could do was protest. All I could feel was rage.

In the middle of January, a month before I would reunite with Justin on my roof, I got an email asking if I’d like to attend the Sharjah Art Foundation’s March Meeting. I was invited to Sharjah’s biennial last year but couldn’t attend and sort of forgot about it. I was at the tail end of my three-month hiatus, fresh from a trip home to California to see my mom. Without thinking much about it, I said yes. I was sent an itinerary and was told everything else would be figured out for me.

In the one month after receiving that email, I fell into an uncharacteristic yet periodic bout of partying. I was sleeping all day when I wasn’t working part-time for a friend. I was no longer protesting. I was numb. I was comfortable. I wasn’t troubled anymore. I wasn’t anything at all.

The invite confused me. Didn’t they know that I was no longer a writer, that I was just a body taking space atop a floating rock?

As Justin and I baked in the pleasant February sun twelve hours before my flight to Dubai, I told him how little I had prepared for this trip and how few expectations I had going into it. Why did I say yes to this? Is this going to be a mistake? Am I ready to go to the Middle East in the middle of everything going on?

Save for a layover in Dubai in 2018, I’ve never been to the Middle East (not for not trying). My dad worked for three years to get me an Iranian passport, which I finally received one month into Covid. Right when the travel restrictions began to lift, freedom protests erupted, and I decided that it was no longer a good idea, especially with my status as a journalist. I had all but given up on the Middle East, on leaving New York, and truly on having any serious desire for doing anything besides sleeping and partying.

Justin, with ease, responded to my concerns, “You’re going to get there, it’s all going to click immediately, and you’re going to make it your own.”

Forty-eight hours later, I’m in a cab in Sharjah, and I’m covered in curry.

I’ve been in the country from about four hours. In that time, I landed, made some friends with the other art writers, took a twenty-minute nap at our beautiful hotel, and got bussed to lunch. I arrive a little early, before the larger press group arrived from a tour at the Sharjah Art Museum. I greet all my compatriots in the art world. Writers from Japan, London, others from New York, Paris, and Milan, and all of them, distinguishably, had some sort of ties to The Region or, by extension, East Africa, all now living and writing in the West. It felt like the first day of school. I could hardly form words. I was so hungry. My mouth watered as I saw so many dishes I recognized from Persian cuisine. Fish, beef, and chicken kabob. Additionally, daal. Saag paneer. Stews and curries I had never tasted before. Spices I was very familiar with. It was like a warm blanket.

While speaking to a journalist from London, I put a little too much energy into my kabob carving, and curry flew all over my entirely white outfit. I snuck away and started out into the street, looking for somewhere I could buy a change of clothes as I didn’t want to miss the events of the day. Then I started looking around, perhaps for the first time since landing in the country, with serious intent. I had no idea where I was. Not just on this street but in this country. This region. The Middle East. I had arrived in my homeland. And I was totally lost.

I called an Uber home, quickly changed, and hailed a cab from the hotel. And I started to really look, now, at everything around me. Mosques everywhere. There are over 3,000 mosques in Sharjah. I joked with one of the cab drivers that I was seeing more mosques than people.

According to Gulf News, “Guided by the vision and directives of His Highness Sheikh Dr. Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi, Supreme Council Member and Ruler of Sharjah, Sharjah has ensured that every single part of the Emirate, feted as the Cultural Capital of the Arab and Islamic world, has a mosque to cater to the needs of the faithful.”

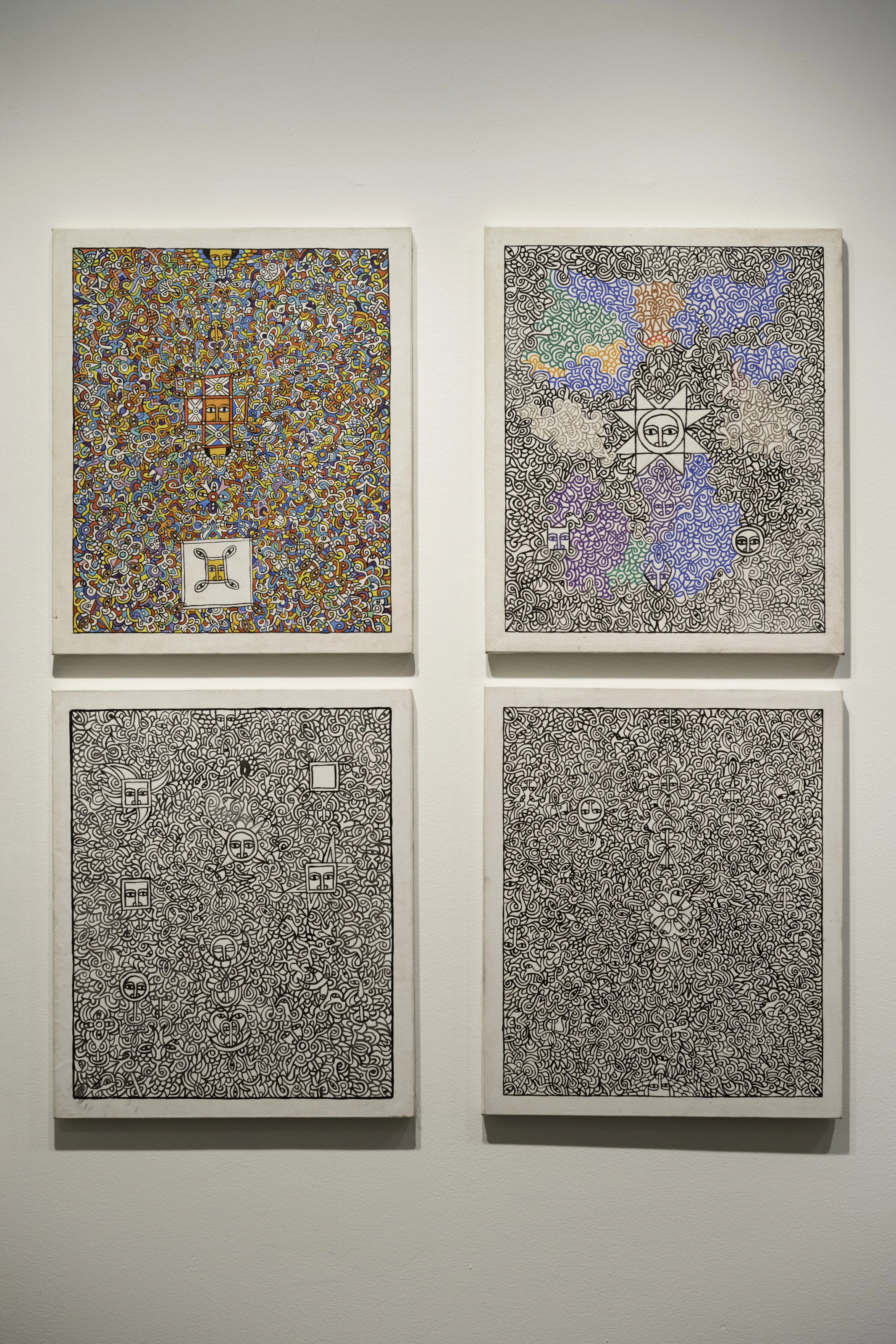

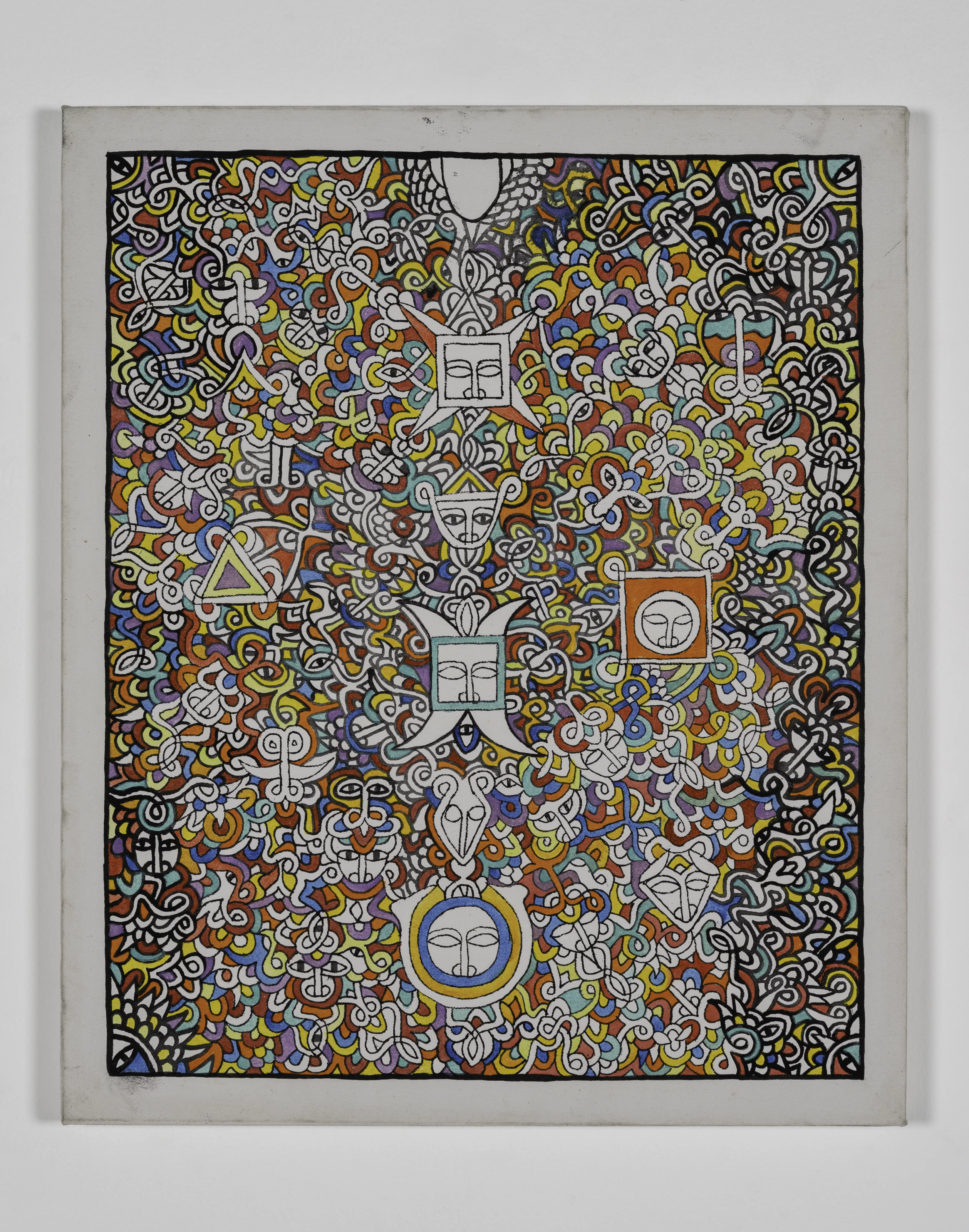

After jokes from my new friends about my new clothes, I started to observe the art by Henok Melkamzer in his exhibition, Telsem Symbols and Imagery, in collaboration with The Africa Institute, Global Studies University (GSU), and Sharjah Museums Authority.

I felt myself slip into a trance while I looked over Melkamzer’s works. Gorgeous, cerebral, patterned, flush with colour and personality, every single piece. There were over one hundred pieces in the exhibit, Melkamzer’s first international solo show. I couldn’t look at them fast enough. I wanted to spend an hour looking at every single one. They were all so vibrant, so alive.

The following is from the Sharjah Art Foundation’s press release on the show:

“Engaging with astrology, religion, and spirituality, telsem art interweaves symbols, drawings, and texts imbued with spiritual and philosophical significance. Although it was originally deployed to heal personal ailments, it has been shaped over centuries into its current manifestation by the sociopolitical and cultural histories of Ethiopia. Henok’s practice expands the use of the form, combining ancient inspirations and modern idioms to contemplate and unravel the complex ailments of the contemporary world, including climate disasters, war, and poverty.”

I was within Melkhamzer’s field of vision with his work. He saw me. He watched me. He felt the energy I was emitting toward the work. But I could not see him. Or, rather, I saw millions of him, millions of moments that shaped the artist, but enough too that pieces of the work could float away into a wider creative consciousness. It was his work, yes, but it felt like work that had always been. It almost felt like I was in a natural history museum, observing some lost art from an unknown millennia ago. It was a rare, stupefying and life-giving moment to see an artist not as a creator but as a messenger. I felt a vibration through the walls of the Sharjah Art Foundation, all connecting to each other through the tapestries that appeared on them. I existed for those moments, not as an observer but as a momentary change in frequency from an eternal song.

Words by Saam Niami