It’s 12 pm on a Saturday, and I’ve just jammed a load of bedding into the washing machine. That means it’s time to listen to some music. I never used to mind the noise of the washing machine. I’m not somebody who gets taunted by the ticking of a clock, for example. But chronic fatigue means I spend far too much time in this brittle excuse for a house, and the sounds it emits are really starting to grate on me. The taps take turns dripping; one of the gutters is split, focussing heavy rain like a power shower against thin windows; and something is beeping next door, but nobody lives there, so I cannot get it to stop. Then there’s this washing machine and its grand finale of a spin cycle when the janky second-hand white slab bullies the cupboards on either side of it, and the whole thing tremors way out of position. It’s only doing what it’s supposed to do, and yet it makes me vibrate with anger like I’m trying to perform the machine’s movements myself. I close the door between us, amp the volume on the sound bar, and let music replace the soundtrack to my rental life.

I’ve always been an album person. Maybe it’s my age and being conscious of music before Spotify was a thing. Maybe it’s the fact my Mum alternated between two CDs in the car: David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Sawdust and the Spiders from Mars from 1972, and Roxy Music’s Avalon released ten years later. I think if I was in charge of the world, musicians wouldn’t perform bitty setlists at gigs with surprises and covers and encores. They’d deliver fully formed albums from beginning to end. I have just always enjoyed the ordered nature of an album where songs are settled so that there is a story stretching across them. A tentative beginning, a journey into the unknown, a struggle, a recovery, and a return back to normality once the chaos and fiction is done. I can’t be doing with playlists because they interrupt the original arc, and now, when I press play on something, I do so knowing I have to see it through. My favourite album, which ticks these neurotic boxes (and which may or may not match the exact length of the quick wash I just selected) is Blue Weekend, the 2021 release from London-based four-piece Wolf Alice.

Described as ‘a masterpiece of confidence and magic’ by Rhian Daly and adorned with 5-star ratings on NME and The Guardian, Blue Weekend was shortlisted for the Mercury Prize and reached the top 10 on an array of best album lists for its year. Critics agreed it was the band’s best work and — yeah, I’m going to defer to them. In all my years in criticism, I haven’t gone near music. I don’t know enough about it. I honestly can’t tell you what sound is coming out of what instrument or talk sense about mixes. In place of any real expertise, all I know is the way this album makes my body feel; the way the first song rises in my throat like a great cry but ends before any tears spill over, and how those tears wait on the edge of some dynamic emotional verge for the rest of the album’s story, right until its watery sunrise of an ending when I come back into myself, breathing out, and realise I don’t feel the need to cry anymore now that the blurry weekend is over and the days in front of me are clear again. God, I listen to it all the time.

When it’s not cleansing the sound of the bastard washing machine, it’s distracting me through noise-cancelling headphones while I sit for a lifetime in the doctor’s waiting room or buoying me around Tesco. Twitching through rock, indie, punk and rousing ballads, the songs on Blue Weekend might not have anything to do with me, yet I seem to cling to them. The lyrics cover vices, exes and execs, but there is a constant subtext through the album about balance. Feeling smaller than the environment you’re in, feeling weaker than the situation calls for, feeling lesser than the person you’re in a relationship with. Setting those stories against music that is, by comparison, lofty and cinematic, the music protects and bolsters the careful heart of the album’s story. It holds that vulnerability very carefully. In a way, it feels like the members of Wolf Alice — Ellie Roswell, Joff Oddie, Theo Ellis and Joel Amey — are protective older siblings, even though we’re probably the same age. I can imagine them leaning forward while they play, telling the people who’ve wronged them to back off but also bear witness. They feel older, I suppose, because they are so bold.

Now, I didn’t know Wolf Alice until Blue Weekend, which came out in 2021, the same year Long Covid came for me. I have never seen them live, and I’m not sure I’d be able to. But in lieu of declaring myself a fan in a room full of other fans, I have bought the physical CD even though it’s 2023, and got myself two shirts from their website. I have gone through their entire catalogue in a bid to catch up, and in my spare time, I do this thing where I watch the band’s live performances on YouTube and sing loudly on the couch, pretending I’m there. Is that sad? I don’t care because I love it. I could caveat this by explaining my condition, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, means the longer I stand for, the faster my heart rate gets and the worse I feel; as much as I’d like to, I can’t wait around in a festival field or dance on sticky venue floors. I have to be a stationary fan. I have to sing on the couch! Plus, I’d have to be a jobless roadie with unlimited money and energy to catch every one of these gigs that fans have committed to YouTube. Thank god for all of the unedited shaky phone footage; that’s exactly how the stage would look like to me if I dared to go to a gig — dizzy and very far away.

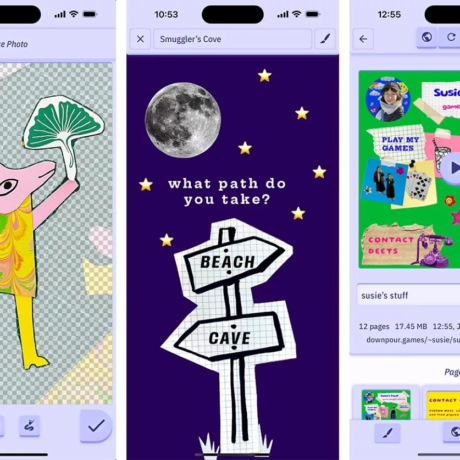

If shaky phone footage is not to your standard, in 2021, Wolf Alice also released a visual album of Blue Weekend. The film, directed by Jordan Hemingway and shot on 16MM film, is a heady manifestation of the music. We follow the band from a bathtub to a taxi, onto a night out in a pub where they perform and have their songs performed by others at karaoke before the four catch the night bus back home. Visually, it’s like neon lights haloing out in the dark. There are pushed colours as in a giallo film, cameras seemingly mounted like Darren Aronofsky did to his actors in Requiem for a Dream, Lynchian references in kaleidoscopic shots and smoking structures, as well as pared back scenes of Roswell set against bright lights like David Bowie performing Heroes. It’s a trip. On the album, Roswell’s chamber choir voice is so full of concern I automatically feel like there is something I should be concerned about, too, almost wishing this stuff happened to me instead. That’s how guttural it gets. To see that emotion performed against a backdrop of fire or slumped inside a toilet cubicle in the pub in this tilting cinematography, it’s confirmation of the anxious, glorious places Blue Weekend takes the listener. Now, the viewer can come, too.

We all imagine music videos when we’re listening to music, don’t we? The perfect opportunity of imagination, where things like budgets and physics don’t matter. Ever since I watched Beyoncé give Lemonade the visual album treatment back in 2016, I’ve wanted all good music to come with its own tailored film. To my dismay, long-form music videos are still not a common add-on. It’s no wonder, really. When the production of so much contemporary art is contingent on how much money that art can generate in the long term, I really appreciate the fact that visual albums are just convoluted gifts given away free to fans. Not all listeners will know the work exists; not all of them will care. So many labels opt for lyrics videos nowadays to save even more money. It’s boring. Yeah, I think it makes me like visual albums even more, knowing they are made for expression, not profit. It certainly enriches my sense of the music when I can’t get close to the kind of electricity I might feel in a crowd at Glastonbury, and I do hope the form is fulfilling to musicians in the same way that writers enjoy having their novels adapted for stage and screen.

Anyway, housework is my Blue Weekend, and unfortunately for me, it’s time to hang the washing.

Writen by Gabrielle de la Puente