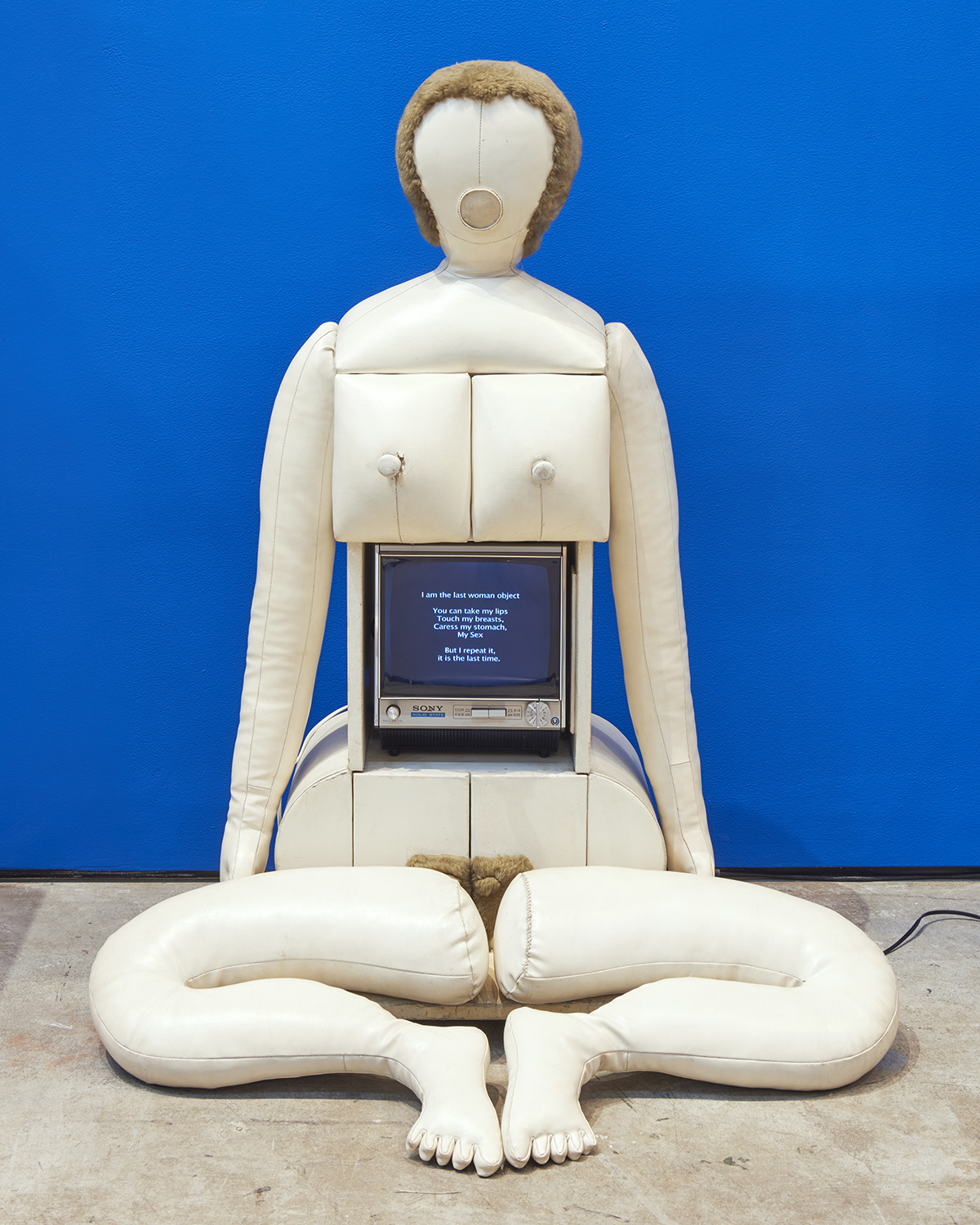

In 1969, the French artist Nicola L was invited to exhibit her lacquered vinyl soft sculpture in the shape of a female body in the window of an upscale Parisian boutique. Titled Little TV Woman: I Am the Last Woman Object, the padded in-built wooden drawers stood for breasts (their knobs read as nipples), and a small television monitor appeared in lieu of a stomach. The English text on the monitor screen translates the French audio track, in which the artist announces, “I am the last woman object / You can take my lips / Touch my breasts, / Caress my stomach, / My sex. / But I repeat it, / it is the last time.”

It was through encountering TV Woman nearly fifty years later, when it was exhibited in The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern in 2015, that I first discovered Nicola L’s work, shown alongside Kiki Kogelnik’s dismembered and stretched bodily hangings and Evelyne Axell’s psychedelic, libidinous paintings. All exemplify what the genre of Pop—often seen as a machismo movement—had looked like when in the subversive hands of female artists.

Against the heady backdrop and revolutionary spirit of the late 1960s, Nicola L’s early Pop-aligned practice explored female sexuality, consumerism and the domestic sphere, often blending conceptual ideas about the arts with an understanding of design and craft. Deemed “functional sculptures”, these works often took the form of anthropomorphized sofas, cabinets, and lamps. Exemplified by La Femme Commode—a wooden wardrobe in the clichéd curvaceous shape of a woman, with drawers for each body part—or the multiple manifestations of the beady Eye Lamp and puckered red Lips Lamp (all 1968–69). Nicola L understood her practice as fully utilitarian, these were artworks but they were designed to be used, and she even furnished her own apartment with them.

“Nicola L’s early practice explored female sexuality, consumerism, and the domestic sphere”

During the same period (1967–70 to be precise), the Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow began experimenting with transforming polyester resin casts of bodies into quotidian objects, as prototypes for mass production. There were desk lamps in the form of lips or breasts fitted with electric bulbs, cushions in the shape of a protruding stomach, and an ashtray manifested from the crushed crown of a head. A survivor of the Holocaust, there is evident historical trauma and violence latent in Szapocznikow’s use of materials, but there is also sensuality and provocation to be found in the abjection. Like Nicola L, there is a clear resistance to the sterility of commercial Pop.

La Femme Commode has been compared to Salvador Dalí’s infamous foray into polymorphous perversity, Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936), in which a miniature replica of the iconic statue was transformed into a bureau with handles made from white mink fur (the favoured material of fetishism, as consecrated by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novella Venus in Furs—and later by the Velvet Underground’s 1967 song of the same title). The “chest” reads as a double-entendre, as both an object and a torso. A similar motif occurs in the British designer Alan Aldridge’s poster for Chelsea Girls

, the 1966 underground film directed by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey that followed the lives of women living in the iconic New York Chelsea Hotel. Alridge represents the hotel as a naked female body, complete with windows and an open door configured as the vagina. Warhol reportedly preferred the poster to the film.

The rudimentary, symbolic relationship between the female body and functional objects displayed by Dalí could also be compared to the work of Allen Jones, particularly his controversial “furniture women”. In 1969, Jones exhibited a series of fibreglass female mannequins, dressed in bondage—black leather underwear, elbow-length gloves, kitten-heeled thigh-high boots—arranged on white shag pile rugs, their bodies reduced to sexualized household objects: Hatstand, Table and Chair. Jones’s work has spawned multiple pastiches, notably the inspiration for set designer Liz Moore when she worked on the interior of the Korova Milk Bar for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), in which mannequins are used as tables, or as drink dispensers for moloko plus (the milk is drawn by squeezing their breasts).

“The symbolic relationship between the female body and functional objects displayed by Dalí could also be compared to the work of Allen Jones”

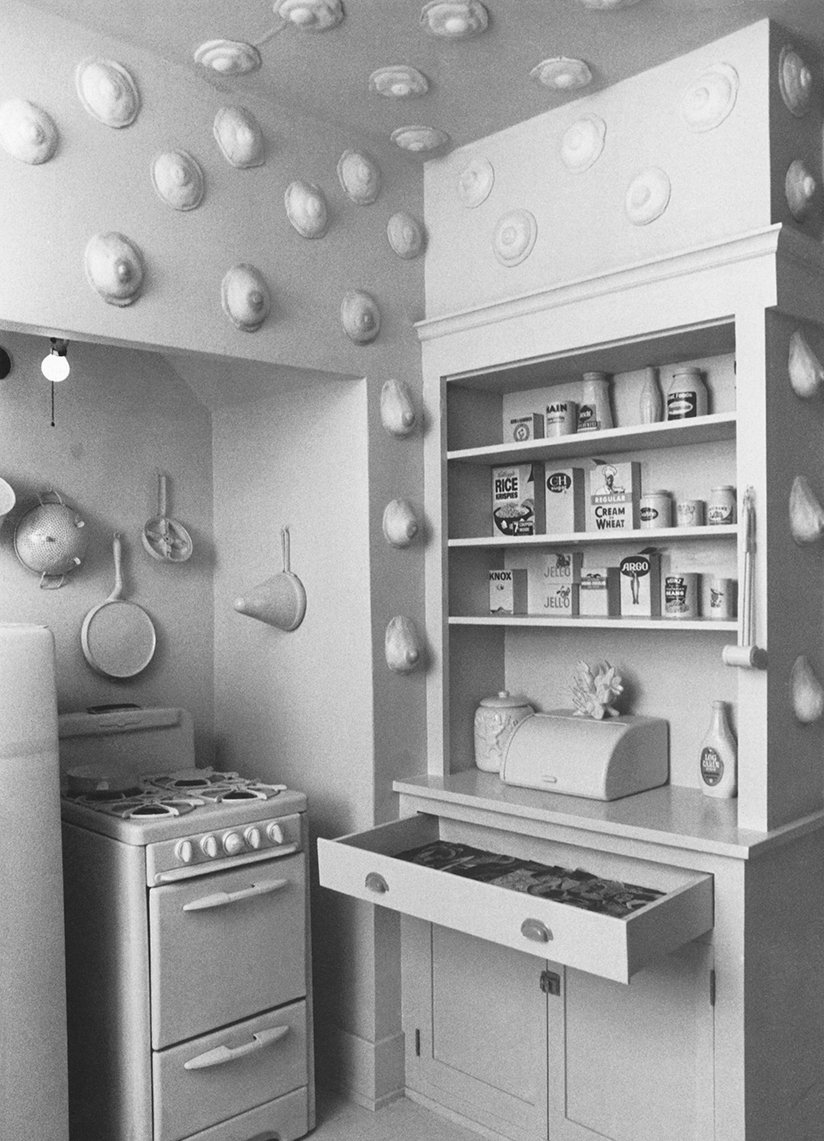

- Left: Sandy Orgel, Linen Closet, in Womanhouse. Right: Susan Frazier, Vicki Hodgetts and Robin Weltsch, Nurturant Kitchen, in Womanhouse. Both courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Institute Archives

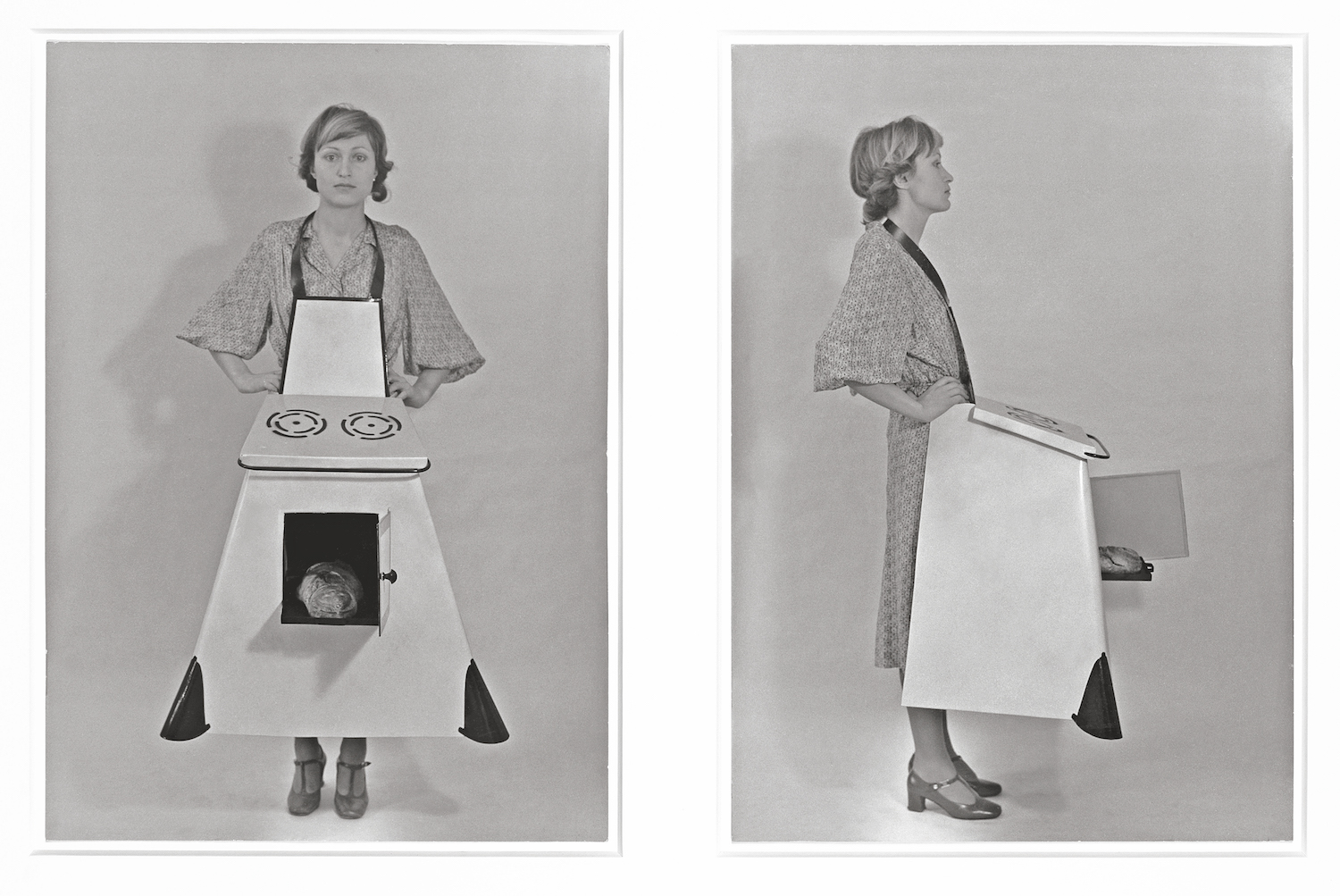

The notion of the woman’s body as a cipher—or merely a replacement—for the domestic instrument was surveyed in much of the feminist art produced during the second wave women’s movement, such as Birgit Jürgenssen’s Housewives’ Kitchen Apron (1975)

in which she donned a wearable sculpture in the shape of an oven. In 1972, led by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, a group of women enrolled in the feminist art programme at the California Institute of Arts worked on an installation called Womanhouse. Sandy Orgel created a linen closet in which a nude female mannequin was affixed inside the cupboard, ossified between the drawers, later remarking, “As one woman visitor to my room commented, ‘This is exactly where women have always been—in between the sheets and on the shelf’.”

“Sarah Lucas’s early sculpture fused banal furniture with food, executed through an astute language of reduction and visual punning”

The Womanhouse group who worked on the Nurturant Kitchen portrayed fried eggs covering the walls and ceiling, slowly transforming into breasts. However, the most familiar evocation of eggs as breasts is clearly in the work of Sarah Lucas. Her early sculpture fused banal furniture with food—wire hangers, kitchen tables and sagging mattresses met raw meat, fish, fruit and vegetables—executed through an astute language of reduction and visual punning.

In the early 1990s, Lucas first exhibited the now infamous Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992), constructed as a set of symbolic codes to be read as a female body, which in turn implicated the viewer via their interpretation. In this inaugural showing, Lucas replenished the food every day, buying the kebab en route and frying eggs on a Primus stove on site. “I treated it a bit like a performance. A heck of a lot of people came and stood looking in the window and I’d tell them to come in but they’d just scuttle off,” she explained in 1994, “I felt a bit like a dirty old man.”

All of these artists, from Nicola L to Alina Szapocznikow to Sarah Lucas, turn the male fantasy inside out, pushing the misogynistic point-of-view to the point of absurdity. There is something playfully perverse about the exaggerated and shorthand iconography used in the surreal conflation between furniture, function and bodies, with results that are both accessible and universal.